If a mediumweight French brewery had not been looking for another beer to add to its portfolio in the early 1970s, and if the owner of a drinks distribution company in County Wexford had not also owned a striking ginger beard, we probably would not now have that totally fake beer style, Irish Red Ale.

The story begins in 1974, when the Pelforth brewery of Mons-en-Barouel Barœul, near Lille, in north-east France, decided that it needed to expand its line-up of beers, and went hunting abroad for a foreign brew to make under licence. Pelforth had been founded as Brasserie Pelican in 1921 by a merger of three war-battered breweries around Lille, and owed its name to a beer invented in 1937, which its inventor, Jean Deflandre, called Pelforth 43, because it contained 43 kilos of malt per hectolitre of beer. The “Pel” part came from “Pelican”, to which Deflandre added “fort”, the French for strong, and a final “h” to make the name look more English. The beer became so popular that in 1972 Brasserie Pelican changed its name to Brasserie Pelforth.

Pelforth went to England, Germany and Sweden looking for suitable “traditional” beers to add to its portfolio, and also contacted the French embassy in Dublin to see if it knew of any Irish brewers who might be making something suitable. The embassy in turn rang G.H. Lett & Co, a beer and drinks distributor in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, 60 miles south of Dublin, which had operated as a brewery until 1956, and still kept up its brewer’s licence. The then head of the firm, 48-year-old George Lett – known to everybody in Enniscorthy as Bill, probably because his father and grandfather were also called George – expressed willingness to meet the people from Pelforth, who duly turned up at the Mill Park brewery to study its brewing records.

Lett’s had made three beers just before it stopped brewing: Wexford Pale Ale, Ruby Ale, and Lett’s Strong Ale, the last selling for a shilling a pint. Later, revisionist history claimed it was the recipe for Ruby Ale that Pelforth took away and turned into George Killian’s Bière Rousse, a 1067º OG, 6.6 per cent abv, ruddy-coloured beer put into clear glass bottles. It was, apparently originally going to be “George William’s Bière Rousse”, based on Lett’s nickname, Bill, though his “real” middle name was John. However, there was a Dutch aperitif on the market called John William, and Pelforth’s lawyers feared copyright problems. Instead, Pelforth’s advertising agency invented a new middle name for Bill Lett, Killian, Killian being an Irish saint, and so, for advertising purposes, he became George Killian Lett. He was, apparently, “greatly amused” by his new name. (Hat tip to Gary Gillman for unravelling the story of Lett’s names.) Newspaper reports from the time, however, make it crystal clear that the beer Pelforth based its Bière Rousse on was Lett’s Strong Ale. In 1980, Bill Lett specifically stated: “In 1974 members of the Pelforth brewery visited us. Eventually I sold the recipe for Lett’s Strong Beer to them. They renamed it ‘George Killian’s Bière Rousse’.”

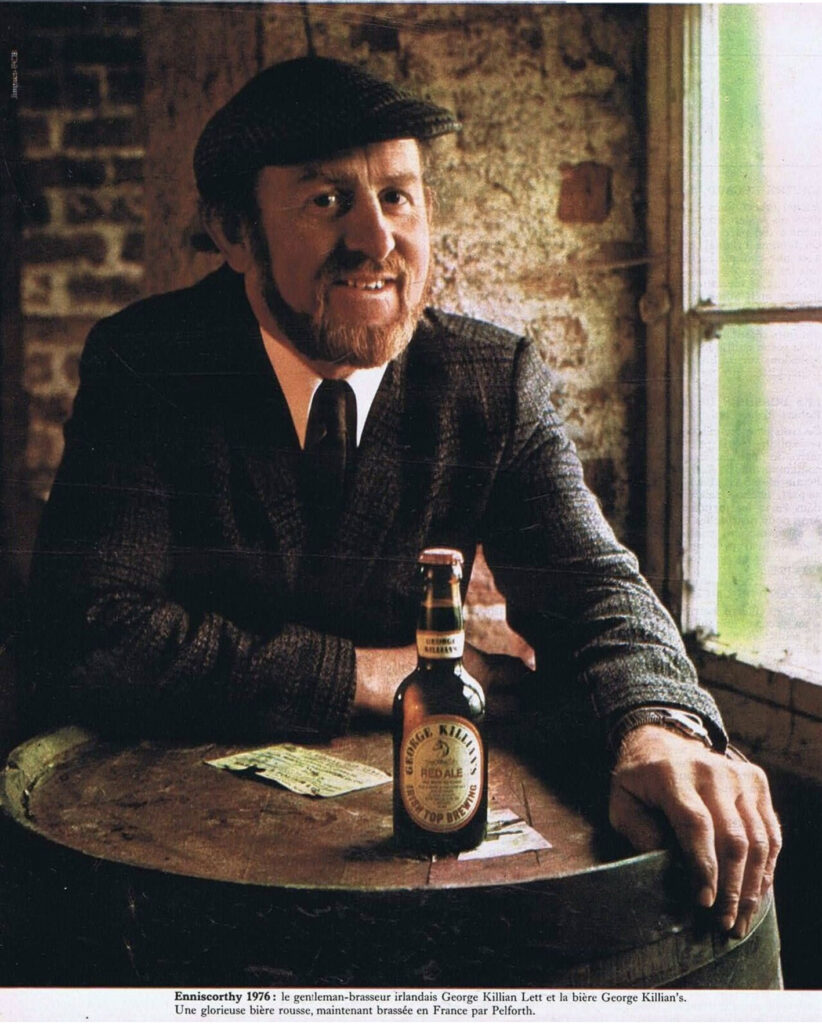

Pelforth also used Bill Lett – under his invented name, George Killian Lett – as the “face” of Bière Rousse in its advertising, his red hair, ginger beard, dress style and very Irish-looking face clearly matching the French idea of an Irish “gentleman brasseur“, as the advertising in France for the beer called him, as well as his hair and beard chiming with the image of a brewer of “bière rousse“, red beer. (French uses roux/rousse for red hair and red beer, with a sense closer to English “russet” or “ginger”, rather than the standard word for red, rouge.) Lett’s wife, Phoebe, told the Irish Farmers’ Journal: “They couldn’t get over how traditionally Irish Bill looked, with his red hair and beard.” According to the Irish Independent, “The French were so taken with the sheer Irishness of George, his red hair and beard, colourful tweeds and his easy cheerfulness, that they straightaway decided not only to name their new drink after him, but also to feature his comely countenance in their publicity material.” The irony that Bill Lett was a descendant of firmly English settler stock whose Protestant ancestor had arrived as a soldier in then war-torn Ireland in the late 1640s, most likely to fight against the native Irish, almost certainly passed over their heads. Instead Pelforth’s advertising for its new beer actually declared of “George Killian Lett”, the “gentleman brasseur“, that “sa barbe était rousse! Aussi rousse que sa bière …”

In 1981, the Colorado-based brewery Coors launched its own version of Pelforth’s Bière Rousse, as George Killian’s Irish Red Ale. Later accounts claimed that Pete Coors, nephew of the company’s chairman, Bill Coors, fell in love with the beer and “convinced George [sic] to allow him to brew it in Colorado.” This is more revisionist nonsense. In fact, Pelforth approached Coors to see if it was interested in brewing Bière Rousse for the American market, and Coors’ new head of marketing, John Nicholls, who was looking for a “superpremium” beer for the company’s line-up to compete against the Michelob and Henry Weinhard brands, persuaded the Coors board to sign up to make the beer under licence.

The Coors version was 11 per cent weaker than the Pelforth original, at 5.8 per cent abv, because Bill Coors felt the French version was “too bitter, too filling”, but the promotion of the Colorado-brewed beer was just as full of blarney as Pelforth’s advertising. Late in 1981 Coors sent the Canadian actor Christopher Plummer to Ireland to film a series of advertisements for its version of George Killian’s Irish Red Ale. Plummer, best known for playing Baron von Trapp in The Sound of Music, was filmed dressed in tweed cap and jacket while standing on a hill overlooking Enniscorthy and proclaiming the excellence of the beer, in a dreadful joke of an Irish accent.

One question remains unanswered: who invented the expression “Irish Red Ale”? It was, presumably, someone in the Coors marketing department in Golden, Colorado: Pelforth called their version “Bière Rousse“, without adding “Irlandaise“. The term “red ale” was unknown in Ireland, except, as we shall see, among scholars of Irish mythology. The name of the originator of the phrase “Irish Red Ale” may be hidden somewhere in the corporate archives in Golden: it would be fascinating to find out who came up with the expression.

The promotion by Coors of George Killian’s Irish Red Ale as an “authentic” beer with roots going back, supposedly, to 1864 seems eventually to have persuaded some in the swelling 1980s American craft beer scene that there actually WAS a genuine, historic Irish beer style called red ale. The first small American brewer to make a beer in this “style” seems to have been BridgePort, opened in Portland, Oregon in 1984, which by 1986 was brewing a beer called Paddy’s Special Red Ale, 1046 OG, 4.7 abv, made from pale two-row and caramel malts and hopped with Cluster and Bramling.

Gradually the style spread: in 1992, for example, the Rockbottom Brewing Co in Denver Colorado was making a self-described Irish red ale called Red Rocks Red, while the Buffalo Brewing Co, in Lackawanna, New York State, was brewing a beer it called “Limerick’s Irish Red Ale”. In 1995 a guide to brewpubs and microbreweries in the United States, at a time when their numbers had not yet passed 500, listed some 30 “red ales”, including one Irish Red Ale from McGuire’s Irish Pub & Brewery in Pensacola, Florida, apparently first brewed in 1989, that was clearly designed to beef up the pub’s Hibernian ambiance, together with the corned beef and cabbage on the menu and live Irish entertainment seven nights a week. The same year an American homebrew book offered a recipe for an “Irish Red Ale” it called The Tomboy, 4.75 per cent abv.

Ironically, as Irish Red Ale began to spread across the United States, in 1988 Coors lowered the abv of its own product to 4.9 per cent and reformulated it so that it was now a lager, dropping the word “ale” from the bottle label, and rebranding the product simply “George Killian’s Irish Red”. It had been selling 100,000 (US) barrels a year in 1985, but this was less than one per cent of Coors’ total sales, and the changes were meant to boost the profits from the beer. One result was that the advertising for the beer, which still tried to claim authentic Irish roots, became even more madly unconnected with historical truths, as Coors declared that “In 1864 in Enniscorthy, Ireland, George Henry Lett brewed the first batch of a full-bodied, red-colored lager that would eventually become known as George Killian’s Irish Red,” which manages to cram five pieces of utter nonsense into less than 30 words.

With mainstream rivals such as Stroh now making “red beers”, on St Patrick’s Day 1995 Coors announced that it would be launching Killian’s Brown, a 5.4 per cent abv chestnut-brown bottled beer that would “help Coors establish an Irish family of brands.” Photographic evidence of a surviving tap handle suggests there was also, at one point a “George Killian’s Irish Stout”. Killian’s Brown seems to have been Coors’ attempt to answer the rise in the United States of brown ales such as Pete’s Wicked Ale. But with an Irish brown ale having no more credibility than an Irish red lager, Killian’s Brown seems to have vanished rapidly.

In 1996 the Letts signed another deal, this time with the English brewer Greene King, which launched a “nitrokeg” mixed gas keg beer called Wexford Cream Ale, supposedly “brewed under licence from an old recipe acquired from the Lett family of Enniscorthy.” The launch was in response to the success of Caffrey’s, one of the first of the nitrokeg “cream ales”, launched with a mock Irish heritage borrowed from the former Caffrey’s brewery in Belfast, which had rocketed from zero to a million barrels a year in just 18 months.

Meanwhile, as the number of “Irish red ales” in the United States grew, beer writers began to notice that those few surviving Irish ales, such as Smithwick’s from Kilkenny and Macardle’s from Dundalk, were generally on the ruddy cornelian end of the beer colour spectrum, and decided that these too must be “Irish red ales”. Michael Jackson wrote for the first time in the third edition of his Pocket Beer Book, published in 1991, that “Irish ales are generally full in colour (often reddish),” having not mentioned their colour in previous editions. A couple of years later, he wrote: “Why Irish ales tend towards a reddish colour, I am not sure,” though he also wrote that the remaining specialist ale brewers in Ireland, all owned by Guinness, all also used roasted barley as an ingredient in their ales, which will inevitably give a reddish hue to beers when used at a low level.

The Encyclopedia of Beer, published in New York in 1995, included the genuinely Irish Smithwick’s alongside George Killian’s Irish Red Ale and McGuire’s Irish Red Ale in its entry on “Irish Ale”. Three years later, in 1998, Jackson gave the category his official blessing, listing six beers as “Style: Irish Red Ale”, including the Pelforth George Killian’s, Macardle’s, Smithwick’s, McNally’s Extra Ale from Alberta, Canada, and the curious Kylian (sic), brewed by Heineken (now owner of Pelforth) in the Netherlands.

In fact beers such as Smithwick’s and Macardle’s were firmly in the style spectrum covered by British bitter ales, and it would be difficult-to-impossible to differentiate them from the bitters brewed by, for example, the former Dorset brewer Eldridge Pope: ruddy, malt-accented and lightly fruity. Irish brewers, and drinkers, generally did not use the term “bitter” to describe or label their pale hopped ales, but stylistically they were no different from many English bitters. One theory was that Irish ale brewers had been encouraged to make ruddy-coloured beers by the popularity among the island’s ale drinkers of the cornelian Younger’s Tartan bitter, from Edinburgh, Scotland.

Still, the mythology of Irish Red Ale has proved unstoppable, in part because there is genuine mythology for beer writers to call on. Patrick Weston Joyce, in A Social History of Ancient Ireland, published in 1903, said that old Irish ale was “reddish in colour, as now” (a big hint that ruby ales were popular in Ireland long before Younger’s Tartan), the “red ale of Dorind”, in Kerry, was mentioned in a poem written in Irish in the 8th or 9th century AD, and the “red ale of sovereignty”, or dergfhlaith (an old Irish pun, with “flaith” meaning “sovereignty” and “laith” meaning “ale”) was supposedly served to the king of Ireland by the earth goddessas part of his ceremony of anointment. Pelforth actually referenced this myth in its advertising in French newspapers in 1976, saying that that the “premier roi d’Irlande, Conn” was met one day while riding on his white horse by the god Lug and “une merveilleuse jeune fille qui symbolisait la souveraineté d’Ireland.” The young girl offered Conn “une coupe de bière rousse,” and George Killian’s red beer “descend en droit ligne de cette biére divine,” Pelforth claimed. These antecedents helped convince beer writers that Irish Red Ale was indeed A Thing, leading at least one to declare in 2009: “Red Ale has been brewed in Ireland for hundreds of years.”

Despite Michael Jackson agreeing in 1998 that Irish Red Ale was A Style, the Beer Judge Certification Program in the United States did not include Irish Red Ale in its beer style guidelines until 2004, and it only became a category in the American Homebrewers Association competition the following year.

Today the Beer Advocate website lists more than 2,100 “Irish red ales”. One may regret that some nifty early 1980s marketing has resulted in the birth of a genuinely mythological, fake beer style. However, the existence today of Irish Red Ale as a style does at least mean that an otherwise deeply obscure minor Irish brewery is still remembered fondly.

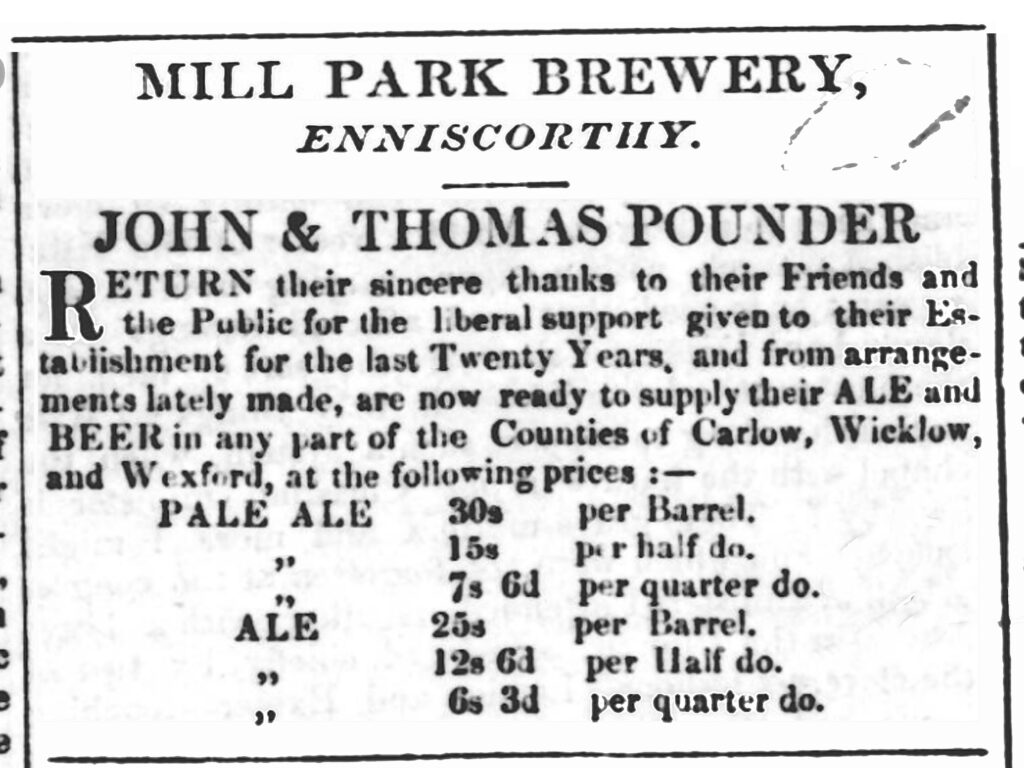

The Mill Park brewery and flour mill was supposedly built by the Pounder family on the site of an old iron foundry in 1810. Some sources have claimed it was in existence as early as 1798. Against that must be set advertisements in Wexford newspapers in 1844 in which John and Thomas Pounder gave “their sincere thanks to their Friends and the Public for them liberal support given to their Establishment for the last Twenty Years,” implying a foundation date of 1824. The Pounders in 1844 were brewing only pale ale, at 30 shillings a barrel, and ale, at 25 shillings.

An iron mill wheel 32 feet in diameter and eight feet broad was erected in 1849, powered by water from a source four miles away at Monart. The brewing water came from a 120-foot artesian well. In 1863 Pounder’s was brewing “sweet ale” (the expression used in Ireland for what was called mild ale in Britain) at 1s 3d per dozen bottles and XXX porter at 1s 5d a dozen, and also porter for private families at 14 shillings to 16s the half-barrel, when Guinness porter was on sale in the town for £1 2s the half-barrel.

A double tragedy hit the business in January 1864 when John Haughton, aged 14, son of the Pounders’ head miller, Edward Haughton, fell between the bull wheel and the mill wall and became trapped. During the attempt to free the teenager from the wheel, one man, Patrick Doran, fell into the wheel himself and was struck on the head and drowned: John Haughton was finally freed, but died the next day.

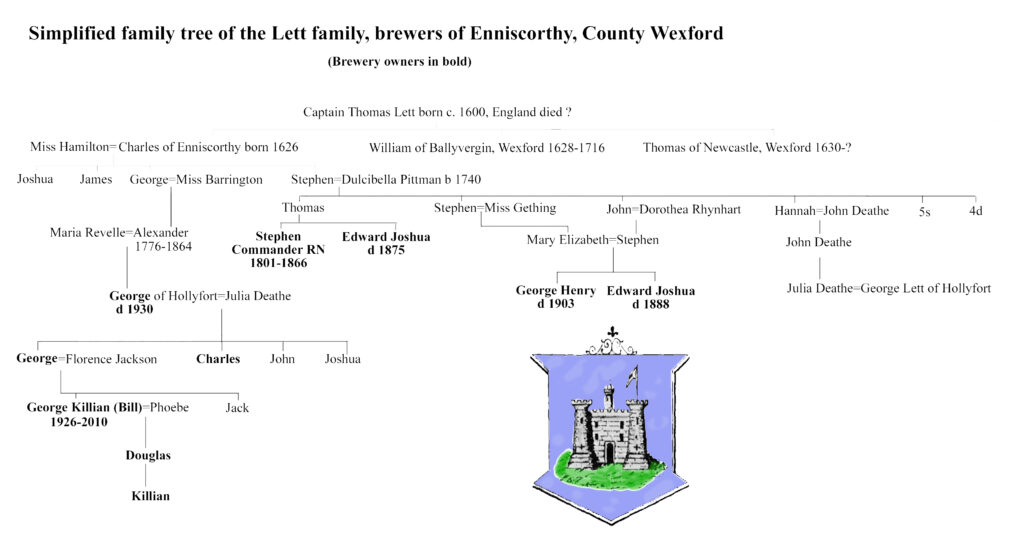

Later that same year the Pounders sold the brewery and mill to two brothers, Stephen Joshua Lett and Edward Joshua Lett, whose ancestor, Captain Thomas Lett, born 1600, had lived in Warwickshire before coming to Ireland in 1648. Captain Lett’s eldest son, Charles, had settled in Enniscorthy, and the brothers were Charles’s great-grandsons via Stephen, his fourth son. Stephen Lett the brewery partner was a former commander in the Royal Navy who had entered the navy at the age of 13, He died just a few months after the purchase, in March 1866, aged 64. His brother Edward, who had been a miller, maltster, brewer and farmer, built a four-storey stone maltings at the brewery which still stands today, albeit disused, with a stone shield on the front of the building declaring: “Erected 1867”. Edward married Helen Cranfield, daughter of the local doctor, in Dublin in 1872, but died in June 1875.

The brewery and milling business was continued as E.J. Lett & Co under the control of the executors until 1881, when it passed to George Henry Lett and Edward Joshua Lett the younger, who were sons of two of Stephen and Edward-the-older’s cousins, another Stephen Lett and his cousin-and-wife Mary Elizabeth Lett (see family tree. The Letts, like many families, enjoyed sharing a small pool of first names across and within generations, probably getting a kick from the idea of messing with the heads of confused later historians.) By that time the Letts were also involved in the artificial manure business, and sending their goods away via the River Slaney and the Dublin, Wicklow and Wexford railway. In 1883 they added “aerated waters”, including lemonade and ginger beer.

Edward J. Lett the younger died in September 1888, aged 31, and the business carried on under his brother George Henry Lett, who died in December 1903, aged 52: in his honour all the businesses in Enniscorthy, regardless of religion, shut their doors until his funeral. With neither brother having children, the brewery passed across the family tree again to another George Lett, who was descended from Charles Lett’s second son, George Lett of Hollyfort, Enniscorthy. The new brewery boss was, again, doubly related to the previous owners: not only was his great-grandfather their great-great grandfather, his wife, Julia Deathe, was their first cousin once removed, via her grandmother, Hannah Lett.

The business kept George Henry Lett’s name, as G. H. Lett & Co and George of Hollyfort ran it until he passed the management to his second son Charles, dying in April 1930 aged 64. Charles and his older brother George continued the business, which eventually passed to George’s son, Bill. In the 1930s the brewery ran a competition for customers to come up with an advertising slogan for the firm, the winner being: “Let’s drink Letts!” By now the Letts’ trading area covered the counties of Carlow, Wexford, Wicklow and Kilkenny, and they also sold their beers in Dublin during the Second World War with “considerable success”.

The Letts stopped brewing in 1956 as the Irish beer industry changed from naturally conditioned beer in bottles to chilled and filtered beers, the company deciding that it could not afford the new machinery required for keeping up with the rest of the market. Instead the Letts concentrated on mineral water manufacturing, and distributing beers made by other brewers. The firm kept up its brewing licence, however, and in 1965 this led to talks with the Milwaukee brewery Schlitz, which was contemplating opening a brewery to serve the European market. The Letts offered to sell the Americans their brewing licence, but nothing came of the discussions. Mineral water manufacturing was discontinued at the Mill Park brewery in 1977, but the firm continued as a drinks distributor.

Bill Lett died in October 2010, aged 84, his hair and beard by now white. Earlier that year he had appeared in an advertisement on American television for George Killian’s Irish Red, happy to ignore the unhistorical claims made about the beer’s origins and his family brewery’s history. Bill Lett’s legacy lives on, even if the story he helped begin, as widely told today, bears little resemblance to the facts. Today G. H Lett & Co is run by Bill’s son, Douglas, and grandson, Killian Lett (full name George Killian Lett), and one of the beers it distributes is O’Hara’s Irish Red Ale, a 4.3 per cent abv ruby-coloured beer described by its maker, the Carlow Brewing Company of Bagenalstown, County Carlow, 20 miles from Enniscorthy, as a “traditional ale”. It’s a “tradition” that began only in 1974 in Lille, France (although today George Killian’s Bière Rousse is, apparently, brewed in Heineken’s breweries in Marseilles and the Strasbourg suburb of Schiltigheim) and came “home” via a brewery marketing department in Golden, Colorado.

Fascinating article – thank you Martyn.

Hi Martyn, Thanks for your informative post! However, your title is inappropriately provocative because it says the ‘Red Ale style’ is ‘entirely bogus’, but your text says that this style is just a renaming of an existing style. Instead of “… launch an entirely bogus style of beer”, I suggest “… launch a new name for an established style of beer”. Oh well 😉

But it’s NOT “a new name for an established style of beer”. It’s “a new name for a subsection of an established style of beer when that subset can in no way be distinguished from other parts of the existing style in terms of ingredients, method, strength or taste”. THAT’S why it’s bogus.

The thing is these Irish brewed reddy coloured ales ranging from copper red to dark ruby are malt forward beers with a caramel or butterscotch or toffee taste with a variety of other tastes as well depending on which Breweries version. English pale ales are more hoppy right. Then does that make them a mild ale.

Fear maith Martyn sorry if in my first comment I come off as harsh. After rereading the article it makes a lot of sense. The Ruby ale connection to Ireland is interesting as is the Lett’s strong ale. It was very funny the story.

Oh, and what ever do you mean by “inappropriately provocative?”? When I’m provocative, which I frequently am, it’s always entirely appropriate.

Interesting article, as always.

Whilst I would agree that the Irish ales, such as Smithwicks, were not entirely different from some British bitters, as a Dorset man who grew up on Eldridge Pope (especially Royal Oak) and whose Grandfather kept an Eldridge Pope pub, I feel obliged to point out that any similarity between Eldridge Pope’s beers and, say, Smithwicks of the keg Bass that you got in Ireland was largely confined to the reddish colour.

Certainly by the late 70’s when I first tried them, the Irish ales were only available as rather thin, slightly tinny keg beers. I accept that I may have been swayed by my much greater familiarity with the Dorset ales, but I honestly don’t believe that the Irish ales were any match for body, aroma, depth of flavour, hoppiness etc etc…

Of course, I completely accept that earlier, non-keg, versions of these beers may well have been far superior.

The Sullivan’s ruby ale is lovely out of a can, bottle or keg.

Thank you for another excellent debunking of manufactured beer history. I remember when the Coors “George Killian’s Irish Red Ale” hit the market here in the States. I had hoped for something flavorful and new. Alas, it was truly and throughly a Coors product; consistent, but uninteresting.

Fascinating article, Martyn. Made a lot clear to me – I often wondered where these Irish Red Ales came from, and now I know. I was familiar with the French beer from much time spent in France in the 80s onwards, and found the style when I went to the US in 97 – I’ve a book similar to the one you mention from that year, which listed several, and I bumped into at least one in person. But I really didn’t know where the style had come from, and – clearly incorrectly – assumed it was similar to Belgian “Scotch” ales in history.

Bogus. Makes complete sense. I always felt it was a bit odd as a style.

Mons-en-Barœul, Martyn.

Merci beaucoup, Joris – corrected …

Excellent article as usual Martyn, thank you.

Fascinating article Martyn, just the sort of debunking I love.

As for Heineken’s Kylian, it was introduced in January 1994, as part of a programme to widen their portfolio on the Dutch market (see: https://lostbeers.com/in-remembrance-of-wieckse-witte/ )

Kylian was brewed for them at Pelforth in Mons-en-Baroeil. It was indeed Heineken’s 6.5% ABV version of Pelforth’s George Killian, though they had tweaked it so that only the yeast was the same and the rest was adapted to ‘the taste of the young, innovatively-thinking beer drinker’, which apparently meant men aged 20 to 35. The Irish connotation was dropped and instead the label featured a globe and a vaguely international feel, as it was a ‘contemporary beer’ that was ‘brewed to be discovered’. The marketing department couldn’t come up with any other argument for the consumer to buy it other than ‘it’s brewed with Vienna malt’.

Kylian was discontinued in 1999, probably because a lack of brand profile (where was it supposed to come from and what style was it meant to represent?) and because in 1994 Heineken had also launched Vos, an amber-coloured Belgian-style beer that had a similar taste.

Thank you very much for that, Roel, a terrific footnote to the George Killian story. Couldn’t call a beer Kylian today, of course, or you’d have Mr Mbappé’s lawyers on your case …

“Irish top brewing” is probably just an odd mistranslation for top-fermentation.

Yes, I’m sure you’re right. My suspicion is that the label was faked up by Pelforth’s marketing department to make it look like the “genuine” English-language label for the non-existent Lett’s “original” Irish Red Ale. The French expression is “fermentation haute”, though, so I’m not sure how that became “top brewing” …

Surely you’ve worked with marketing people before. It was initially translated correctly as top fermentation, then someone else came along and said “doesn’t look English enough, make it brewing instead”.

[…] What, wait? […]

The main reason ‘Irish Red Ale’ was not recognized as a style by the Beer Judge Certification Program was because in that span of years, the B.J.C.P. was distrusting of the Brewers’ Association nudging onto its campus of ‘official‘ beer styles. The B.A. composed the style for its tastings, including the Great American Beer Festival, in which medals were awarded to the top three beers in a specific style.

As far as Saint Patrick’s Day 1995, I accomplished something genuinely unprecedented in both the sports and craft beer fields; outfitting the Chicago POWER indoor soccer team [defunct] in green jerseys sponsored by a craft brewery, the New Haven Brwg. Co. [also defunct].

[…] retaggio che questo nome racchiude da secoli; infine, Martyn Cornell ha pubblicato un piacevole post sulla lunga e importante storia della Irish Red Ale, che ha avuto inizio nel 1974 a… Lilla, […]