The Tipperary pub in Fleet Street, London, has reopened after four years of closure, excellent news, since it’s one of the most attractive little pubs in the City. Planning permission was actually granted in April 2020 for its conversion into office use, but one of the very few benefits of the Covid pandemic was that working from home reduced demand for office space, and that scheme was dropped last year.

The re-opening is connected with plans for the building next door, 65 Fleet Street, built in 1989, empty since 2019, which a property development company called Dominus wants to turn into “high-quality, professionally managed student accommodation”. Dominus also now owns, or controls, the Tipperary, and is behind its reopening, evidently feeling, doubtless correctly, that student accommodation is greatly enhanced if there is a pub next door …

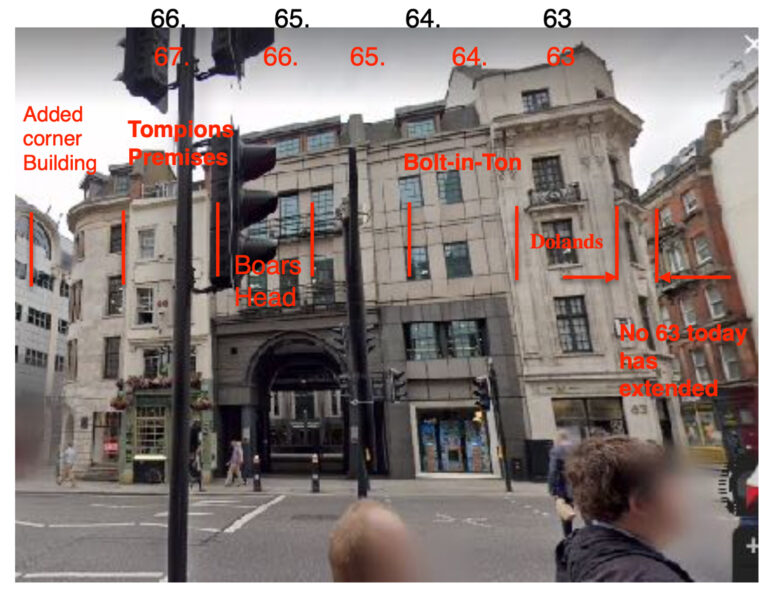

Meanwhile the history of the pub, which is, as I pointed out six years ago, wildly inaccurate in every book and article that mentions the Tipperary, has become even more muddied. The Tipperary is at 66 Fleet Street, and everybody agrees this was originally the address of a pub called the Boar’s Head, rebuilt after the Great Fire of London. Except it turns out not everybody does agree, and the argument has been made that the original Boar‘s Head at number 66 was pulled down in the 1840s, its site is occupied by the modern number 65, the licence for the Bull’s Head was shifted next door to number 67, which was renumbered 66, and a new number 67 was built on previously empty land the corner of Fleet Street and what was then Water Lane and is today Whitefriars Street. Under this narrative, the Tipperary has a much less substantial claim to be descended from the 15th century Boar’s Head, since it sits, supposedly, next door to the original Boar’s Head site.

But before we get to the evidence that has been put forward for that claim, let’s just give another bokk on the head to the received story of the Tipperary, taking as typical the version of its history printed in Johnny Homer’s City of London Pubs, published in 2016:

“The famous Dublin brewery S. G. Mooney acquired the Boar’s Head in Fleet Street around 1700 …”

There was no Dublin brewery called S. G. Mooney. The Boar’s Head was acquired by a Dublin pub company called J. G. Mooney & Co. in 1896.

“[it was] the first Irish pub outside Ireland …”

Total nonsense. It wasn’t even the first pub Mooney’s owned outside Ireland.

“The earliest records of the Boar’s Head date from 1605 …”

“Le borys head”, abutting south on the stone wall of the house of the Carmelite Friars in “Fletestrete”, was part of a grant in 1441/42 by John Stafford, Lord Chancellor to Henry VI, Bishop of Bath and Wells at the time (and later Archbishop of Canterbury), to the Carmelites, or white friars, who gave their name to Whitefriars Street (so called for the long white mantlethey wore over their brown habits when out and about, as opposed to the black friars, the Dominicans, who wore a black one, and the grey friars …). The grant also included the Bolt-in-Tun inn at what was later 64 Fleet Street. Stafford lived at one point in a now vanished street called Elden Lane, near St Bride’s church and off Fleet Street.

“It was one of the few buildings in this part of the City to escape the ravages of the Great Fire of 1666 …”

No it didn’t. The fire destroyed buildings along Fleet Street as far as Fetter Lane, around 160 yards west of the Boar’s Head, and the Boar’s Head was one of those burnt down.

“The Boar’s Head became the Tipperary in 1919 …”

No it didn’t. It was called “Mooney’s Irish House” from 1896 to 1967. Only in 1967 did it become the Tipperary.

“The change of name was inspired by Fleet Street printers returning from the First World War, and a famous old song that had become popular with the troops …”

Wrong again. Any Fleet Street printers who had returned from the First World War would have retired by 1967.

So much for that. But what of the claim that the Tipperary stands on the site of the Boar’s Head, and therefore has a history going back at least 580-plus years? Here I put myself in the hands of a man called Bren Calver, who aggregated many hours of research on the stretch of Fleet Street between Water Lane/Whitefriars Street and Bouverie Street, in particular studying contemporary illustrations, and who is convinced that the Tipperary occupies what was originally 67 Fleet Street, not the post-Great Fire 66 Fleet Street that was home to the Boar’s Head, which Calver believes was demolished around 180 years ago.

This is about to get complicated, so hang on to your hat. But much of the relevant history of the site hinges on the building activities of a man named William Edward Hickson, the wealthy son of a boot and shoe manufacturer based in Smithfield, London, born 1803. Around 1841 Hickson bought 67 Fleet Street with the intention of demolishing it and erecting a “first-class” new building stretching down Water Lane. It turned out that number 67 had no sewer, which cost him £100 – around £11,000 in today’s money – to put right, and annoyingly, as Hickson later complained, the sewer from number 66, instead of draining into the main Fleet Street sewer, ran under the basement of number 67 into a cesspit in Water Lane.

Bren Calver’s contention is that to avoid trying to build over the cesspits in Water Lane, which would have meant unstable foundations, Hickson left number 67 in place and erected his new building, Dunstan House, alongside it. This also, supposedly, removed any problems over party walls.

What happened next, Calver says, is that numbers 65 and 66 were demolished, with a rebuilt number 65 taking over the footprint of number 66 as well, “old” number 67 became “new” number 66, taking on the name and licence of the Boar’s Head, and Hickson’s new building, Dunstan House, became “new” number 67.

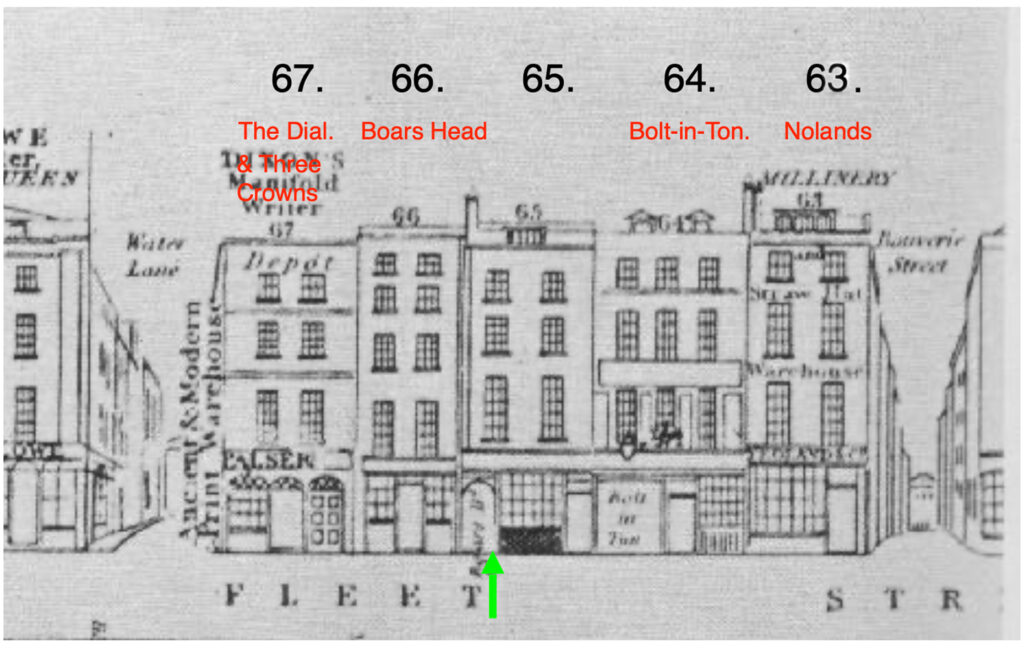

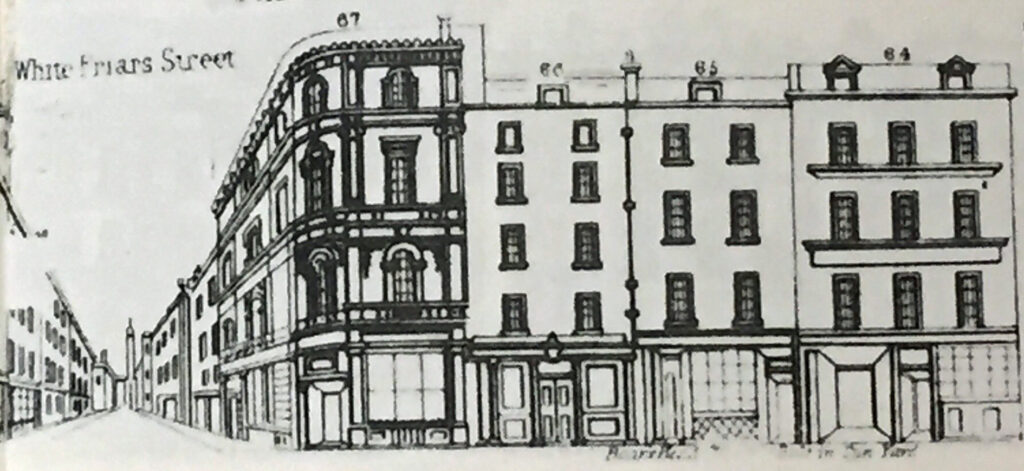

For evidence he puts up drawings of the corner of Fleet Street and Water Lane/Whitefriars Street in 1838, 1842 and 1847, which he says shows how number 66 disappeared and number 65 became wider.

He also queries the lack of a vault or cellar under the Boar’s Head when it was taken over by Mooney’s, so that the Irish company had to apply for permission for a vault to be excavated. The original vault to the Boar’s Head, Calver claims, was under old number 66/new number 65, and it was, he says, discovered in 1991 when building work was taking place on the site, lifted out in one piece and moved a short distance away to Magpie Alley, where it can still be seen.

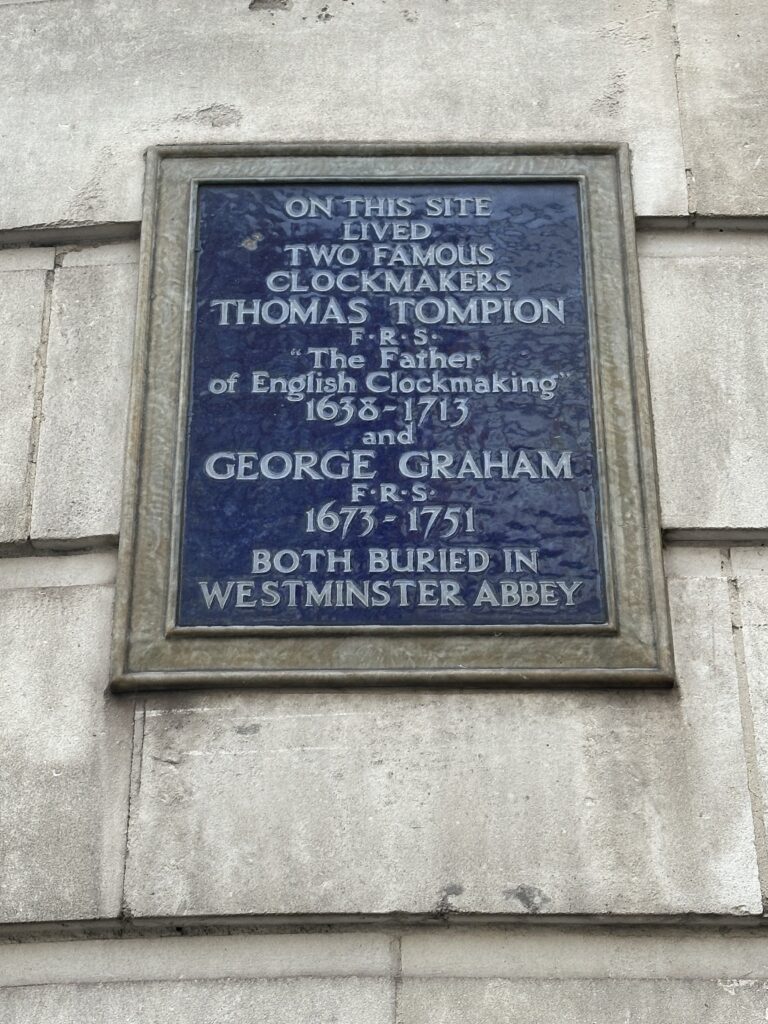

Of that, more in a moment. First, let us tackle the evidence supposedly seen in the drawings. Calver presents a great story, as part of his argument that the blue plaque commemorating two great English clockmakers, Thomas Tompion (1638-1713) and George Graham (1673-1751), whose workplace was at 67 Fleet Street, otherwise the Dial and Three Crowns, is affixed to the wall of the wrong building, the supposed “new” number 67, Hickson’s Dunstan House, and not the “original” number 67, now, according to Calver, the Tipperary. I love a good contrarian, revisionist retelling of received history. But here I’m afraid I believe Calver is wrong: there was no demolition of the original Boar’s Head at number 66 Fleet Street, the Tipperary occupies exactly the same site as the one occupied by the Boar’s Head when John Stafford gave it to the Carmelites nearly six centuries ago, the current number 67 stands where Tompion and Graham’s Dial and Three Crowns stood, and the plaque is on the right building.

The most telling argument against Calver’s claims is the total lack of written evidence in support of his version of history. “Absence of evidence blah blah” – actually, absence of evidence IS evidence of absence, it’s just not conclusive proof of it. But I would have expected at least some mention somewhere of the demolition of number 66, and the transfer of the licence and name of the Boar’s Head to number 67. I have searched extensively, in books and newspaper, and not found any record of those events taking place. Hickson gave a lengthy account in 1844 of the problems he had over the sewer arrangements when he built Dunstan House. Nowhere did he say that he erected Dunstan House next door to the original number 67, nor did he say that number 66, which he complained had a sewer running underneath number 67, was demolished. One might have expected him to allude to these events. Similarly one would expect to find mention of a transfer of licence from old number 66 to new number 66, as for example, the transfer of the licence of the Boar’s Head from Ann Walbancke to Reuben Freeman in December 1846 was recorded.

Instead, references to the Boar’s Head confirm its continuation: The Antiquary, volume 46, 1910, for example, says that “A modern Boar’s Head at No. 66, Fleet Street, between Whitefriars Street and Bolt-in-Tun Yard, on the south side, still occupies the site of the Boar’s Head Tavern destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666.”

As telling, however, if not more compelling, is that the various illustrations Calver puts up as evidence do not, in fact, show what he claims they do. He provides drawings from 1838 and 1847 that he claims show that “old” number 66/the Boar’s Head had disappeared by the latter date, that number 65 had been widened to take over the footprint of the Boar’s Head, and the Boar’s Head had shifted to “old” number 67.

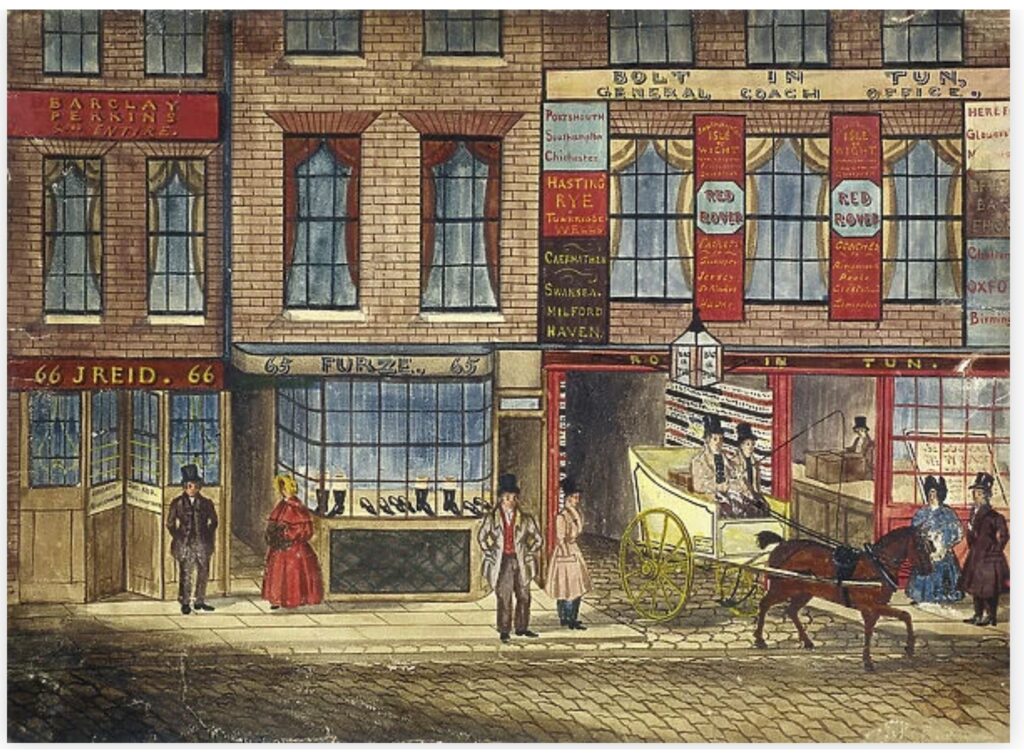

But the drawing from 1847 shows the Boar’s Head still had the same double doors that it did in a painting from 1835 (which painting also shows that the Boar’s Head was selling Barclay Perkins’ Entire, or porter). The entrance to Boar’s Head Court is still between numbers 66 and 65, which it would not have been if 66 was by then occupying the site previously number 67. The 1847 drawing also shows a chimney stack on the boundary between 66 and 65: there is the same chimney stack in the drawing from 1838, but no chimney stack between 67 and 66.

As for the claim that the original vault belonging to the Boar’s Head was found under new number 65 in 1991, I fear Calver is confused. There WAS a vault found on the Whitefriars site, but in Britton’s Court, about 100 yards down Whitefriars Street, and thus nothing to do with the Boar’s Head. This vault, first discovered in 1867 and then forgotten about until 1895, was lifted out in one piece in 1991 to allow for redevelopment of the site, and moved to nearby Ashen Tree Court, Magpie Alley for public viewing. (According to Peter Tombs, the engineer on the project, the vault “basically went back to its original location.”) The vault was identified as probably 14th century, and it probably lay under the prior’s house.

So: sorry, Bren, you’re wrong.

Still, I had fun doing the research, and I uncovered some fascinating new stuff: that the White Friars had a brewery on their site, for example, on the southern edge, hard by what was then the banks of the Thames, which doubtless supplied the brewery with its water (the building of the Victoria Embankment means the site of the White Friars’ brewery is now some 120 yards from the modern river’s edge). Henry VIII “nationalised” the Carmelite priory in 1538 as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and in May 1541 a slice of the White Friars’ site, including “the Brew House”, was granted to Erasmus Crykener and his wife Agnes. Did that brewhouse supply the Boar’s Head with its ale? It seems very possible. The White Friars’ brewhouse, incidentally, was one of at least three religious breweries within less than half a mile: the Black Friars’ priory just the other side of the River Fleet had a brewhouse, and so did Old St Paul’s.

The sale of the brewery to the Crykeners was very probably far from an isolated event: doubtless many former monastic breweries around the country were sold off as Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell closed nearly 900 religious houses across England. Are there later commercial breweries with roots in former monastic brewhouses? I confess I don’t know of any. The former White Friars’ brewhouse is shown on a map drawn around 1635, so it survived for a century after the priory was dissolved, at least.

Another interesting – to me – little titbit was the discovery that it was William Hickson who got the name of Water Lane changed to Whitefriars Street, in October 1844. His complaint was that there were three Water Lanes in the City of London, all close to each other, and he claimed to the vestry of the parish of St Bride that if the Fleet Street Water Lane were renamed, “the value of property in the thoroughfare would much improve””

I also found a photograph from circa 1971, some three years after Mooney‘s had sold the Irish House and it had been renamed the Tipperary, showing the pub was then part of the Chef & Brewer chain. Chef & Brewer was founded by Ezekiel Levy and his brother-in-law, Harry Franks, in 1901. The business was sold to the then hotels and catering operation Grand Metropolitan in 1966. Grand Met, of course, later moved into brewing, acquiring first Truman’s and then Watney Mann. It seems to have sold the Tipperary at some time, and by the mid-1980s the pub was being run by Greene King. By coincidence, after several rounds of corporate pass-the-parcel, Greene King is the current owner of the Chef and Brewer brand …

“…actually, absence of evidence IS evidence of absence, it’s just not conclusive proof of it.”

Very good point and one that is all too often not appreciated (naming no names…)

Interesting post Martyn. Pub history unless it is late 19th century establishment onwards can be very muddled and confused.

Errrmmmm

‘The fire destroyed buildings along Fleet Street as far as Fetter Lane, around 160 years west of the Boar’s Head, and the Boar’s Head was one of those burnt down.’

Yards, or time travel as well? 🙂

Ooops – thank you, now corrected

Remarkable research, as to be expected