The Tipperary, in Fleet Street, has a fair claim to “oldest pub in London” status. You wouldn’t know this from the information you will find about it on the web, in books and magazines, and even the noticeboard outside the pub, which makes much of its storied past. Unfortunately, almost everything written about the history of the pub – including, shamefully, that noticeboard – is wildly, utterly wrong, a staggeringly inaccurate macedonie of untruths, misunderstandings, made-up nonsense, fake news and pure bollix of inexplicable ancestry. What is particularly tragic is that the pub actually has a fine back-story, which has become entirely submerged by layers of invented garbage.

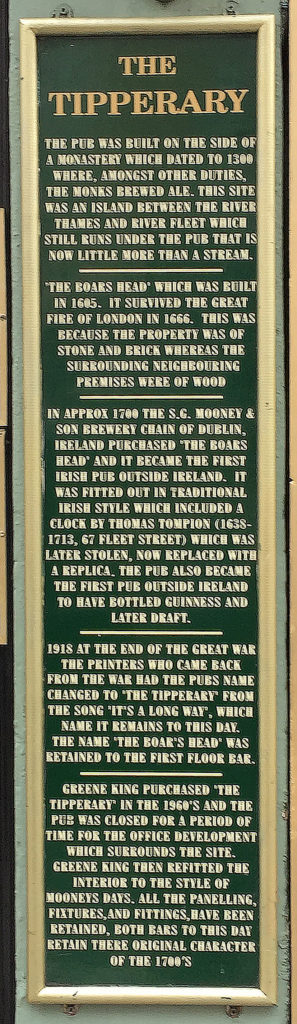

Let’s begin by deconstructing the noticeboard that hails customers as they enter this charming, if cramped, old Fleet Street boozer, with its delightful, slightly shabby shamrock-decorated mosaic floor and dark wood-panelled walls. (We’ll ignore, as much as we can, the grammatical infelicities and spelling errors on the board, though they constitute in themselves a grievous insult to the hundreds, or more, of newspaper sub-editors who, in the times of Fleet Street’s glory as more than just a metaphor for Britain’s national press, walked through the Tipp’s front door in search of liquid relief.)

Let’s begin by deconstructing the noticeboard that hails customers as they enter this charming, if cramped, old Fleet Street boozer, with its delightful, slightly shabby shamrock-decorated mosaic floor and dark wood-panelled walls. (We’ll ignore, as much as we can, the grammatical infelicities and spelling errors on the board, though they constitute in themselves a grievous insult to the hundreds, or more, of newspaper sub-editors who, in the times of Fleet Street’s glory as more than just a metaphor for Britain’s national press, walked through the Tipp’s front door in search of liquid relief.)

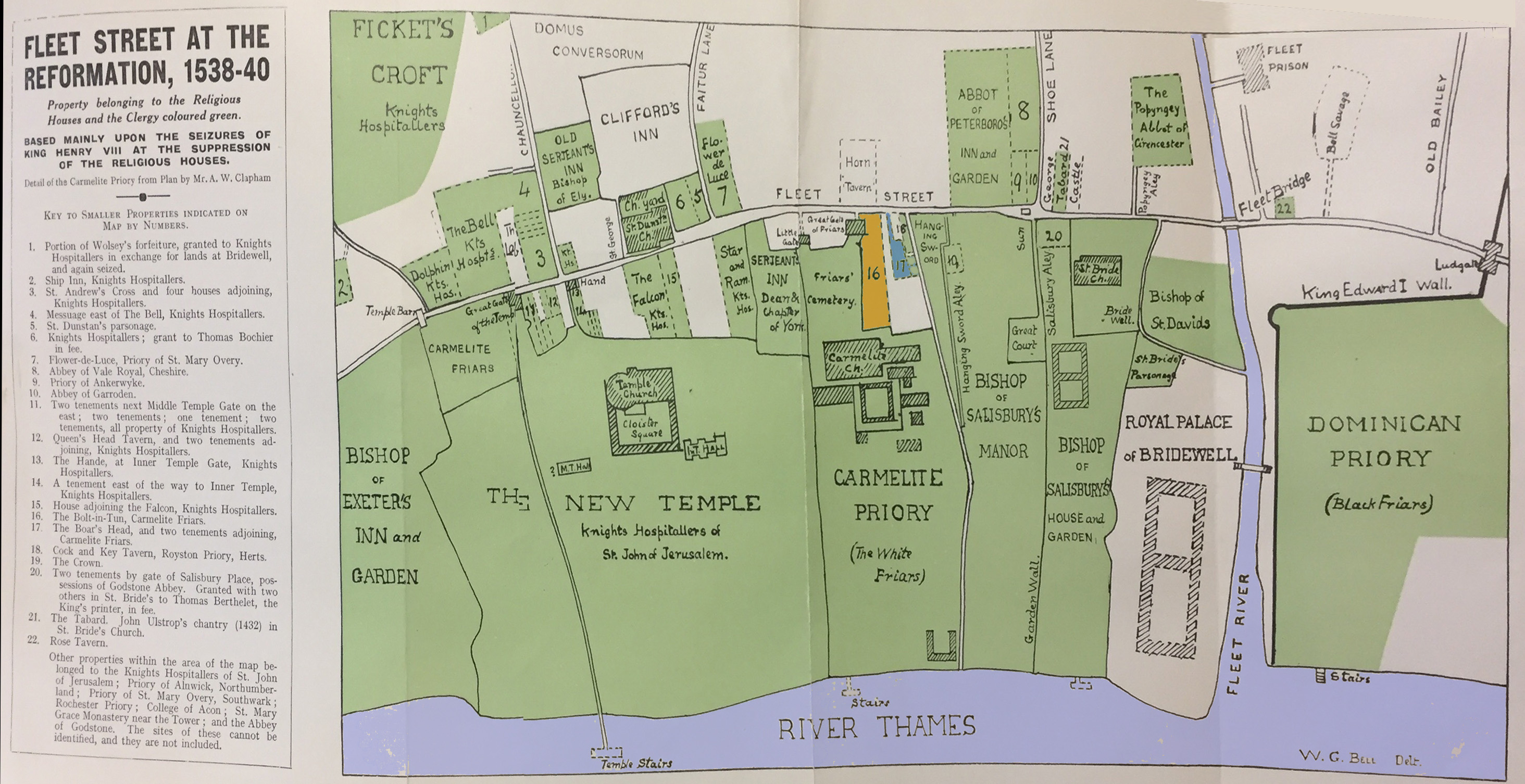

“The pub was built on the side [sic]of a monastery which dated to 1300 where, amongst other duties, the monks brewed ale.” – it was a friary, not a monastery. They were friars, not monks. A house for the Carmelites, more fully the Order of the Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel, was founded by Sir Richard Gray in Fleet Street in or about 1241, not 1300. (The Carmelites, as an aside, originated in the 12th century, and took their name from Mount Carmel in northern Israel, supposedly the home of the prophet Elijah. They were known as the “white friars”, from the white cloaks they wore, in contrast to the black-cloaked Dominicans, the “black friars”, whose main base in London was just across the Fleet river, and whose name is commemorated in a bridge, a railway station and one of the finest art nouveau pubs, inside and out, in the world.)

“This site was an island between the River Thames and the River Fleet which still runs under the pub that is now little more than a stream” – utter steaming garbage. The Tipperary is half-way up the hill that rises from what was once the west bank of the Fleet, which was 250 yards away to the east, not “under” the pub at all. The Fleet ran south along the line of what is now Farringdon Street – indeed, it still does, though now underground and converted into a sewer, which empties into the Thames under Blackfriars Bridge.

“‘The Boars Head’ which was built in 1605” – wrong again, though a rare example of a pub claiming to be much younger than it actually is, since “Le boreshede in Parish of St Dunstan in Fletestrete” was mentioned in the same grant to the Carmelite friars in 1443 as the Bolt and Tun inn next door. (This means, incidentally, that the Tipperary/Boar’s Head is at least 575 years old this year: there are only two or three other pubs in London that can reckon to be older.) “It survived the Great Fire of London in 1666. This is because the property was of stone and brick whereas the surrounding neighbouring premises were of wood.” More ahistoric nonsense. The fire destroyed all of Fleet Street to a point just past Fetter Lane, some 160 yards west of the Boar’s Head/Tipperary, which was one of the 13,000 buildings consumed in the blaze.

“In approx 1700 the S.G. Mooney & Son brewery chain of Dublin purchased ‘The Boars Head’ and it became the first Irish pub outside Ireland … The pub also became the first pub outside Ireland to have bottled Guinness and later draft.” I cannot fathom how or why anyone would invent this stuff, or have it so totally wrong. There is actually a gorgeous old mirror, probably more than 100 years old, on the wall inside the pub which gives the proper name of the pub chain – not “brewery chain”, whatever one of those is — that formerly owned the Boar’s Head/Tipperary, which makes getting the incorrect name outside the pub particularly inexcusable. It was JG Mooney and Co, not “SG Mooney & Son”: the company developed out of the licensed wholesaler and retailer business James G Mooney was running in Dublin from at least 1863. The Tipperary was not only emphatically NOT “the first Irish pub outside Ireland”, it wasn’t even JG Mooney’s first pub outside Ireland. The company acquired its first licensed outlet in London, on the Strand, in 1889, its second on High Holborn in 1892 and a third in Duke Street, on the south side of London Bridge, shortly afterwards. Mooney’s acquired the lease of the Boar’s Head, its fourth London pub, in November 1895. That’s not “approx 1700”, unless you think being nearly two centuries out is “approx”. (Mooney’s was to grow to at least 11 London outlets by 1940, all, or almost all, called “Mooney’s Irish House”: the one in Duke Street was known as “Mooney’s Dublin House”.) Nor, of course, was the Boar’s Head “the first pub outside Ireland to have bottled Guinness and later draft” (sic, again). Guinness was exporting to Bristol from at least 1825 (and to the West Indies earlier than that), in both cask and bottle.

“1918 At the end of the Great War the printers who came back from the war had the pubs [sic] name changed to ‘The Tipperary” from the song ‘It’s a Long Way’ [sic], which name it retains to this day.” But it was being called “Mooney’s Irish House (late Boar’s Head)” in 1895, and Kelly’s directories make it clear that the name of the pub was The Irish House right up to 1967. Only then did it change to The Tipperary. There are no references that I have been able to find to the pub as The Tipperary before this: it was certainly being referred to as “Mooney’s Irish House in Fleet Street” in the 1950s. (Strangely, there is a strong Fleet Street link to the song “It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary”, but it is nothing to do with returning printers. The song’s popularity with the British Army in France in August 1914 was spotted by a Daily Mail reporter, George Curnock, who cabled back to his news editor, Walter Fish that the soldiers were all singing the song as they marched from Boulogne to the front. According to Fleet Street mythology, “Fish visualised ‘Tipperary’ as a great national stimulative, the possible British counterpart of the ‘Marseillaise’, and to his delight found Lord, Northcliffe [owner of the Mail], with his fine flair for judging the public taste, equally enthusiastic. The words and the music of the pantomime song were secured and prominently displayed in the Mail, and from that day on it was on everybody’s tongue.”)

So: four paragraphs, at least 11 clunking, ludicrous errors, all of which could have been avoided with little effort. It took me two to three hours on the interwebs, and an hour in the Guildhall library looking at microfilms and consulting a couple of books, to put together the corrections above, and uncover a more accurate history of 66 Fleet Street. People, this is really not difficult. Don’t just repeat stuff you read – do your own research, because “stuff you read” is quite likely to be wrong.

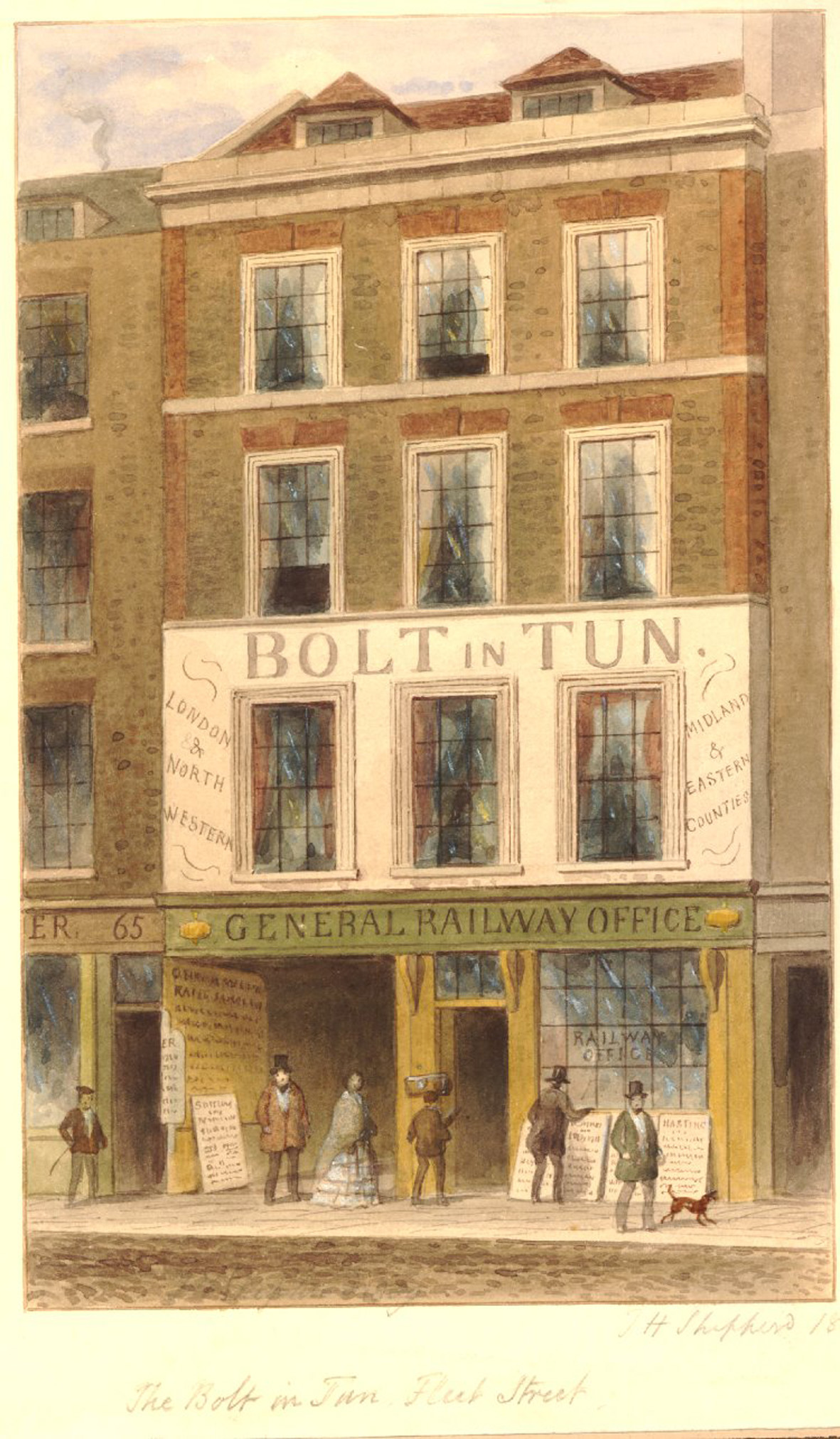

The Boar’s Head originally faced onto Whitefriars Street (named, of course, for the Carmelites, and originally, until at least the 1830s, known as Water Lane). To the south was an inn called the Bolt-in-Tun, with both premises having back entrances dog-legging out on to Fleet Street, at what would later be numbers 64 and 66. (To the east, at what would become 67 Fleet Street, was a tavern owned by Royston Priory in Hertfordshire called the Cock and Key.) In a licence of alienation to the Friars Carmelite of London of certain premises in the parish of St Dunstan, Fleet Street, in the Patent Roll of 21 Henry VI – that’s 1443 to me and thee – “Hospitium vocatum le Boltenton” is mentioned as a boundary. This would have been a building attached to the friary for accommodating guests. The hospitium, or at least a building on its site, was quite probably at least a century older than this, because the wording of an ordinance of King Edward III in council dated 1353 suggests that the road from the bridge over the Fleet to Temple Bar, where Fleet Street becomes the Strand, was by then already lined with dwellings and well-inhabited.

The inn’s name is a pun on “Bolton”, and its sign was a bolt – a crossbow arrow – sticking though a tun, or cask. How or why it was give that name remains unknown. (At least two sources try to claim that the inn’s name is ” derived … from Prior William Bolton of St. Bartholomew, Smithfield”, which is more nonsense on stilts, because while Prior Bolton certainly used the bolt-in-tun as a badge, he was born around 1450, after the first known mention of le Boltenton. It’s more likely, in fact, that Prior Bolton stole the idea of using a bolt sticking through a tun as his badge from the Carmelites’ inn.)

It looks as if the Carmelites used the premises to brew, because after Henry VIII nationalised their friary in November 1538, the list of buildings surrendered included “a tenement for brewing called ‘le Bolte and Tunne'”, and “a brewhouse called Le Bolt and Tunne in the parish of St Dunstan in Fletestrete, which belonged to the late Carmelite Friars there” was leased to one of Henry’s household officials, John Gilman, in 1541. As the only inn on Fleet Street, and thus effectively the first inn on the Great West Road, the Bolt-in-Tun developed into an important base for coaches travelling to Bristol, Plymouth and South Wales. In September 1665 a boy was found dead of the Plague in its hayloft. The Fire of London the following year at least cleansed the city of plague-carrying rats, and by 1704 regular coaches for Windsor were starting from the rebuilt inn. In 1741 services from the inn included “A Handsome Glass Coach and six able Horses” travelling regularly to Bath. Destinations from the Bolt-in-Tun in 1805 ranged from Cardiff to Hastings, and Newbury to Chichester, and in 1817 26 coaches a day left the inn for towns and cities across the south and south-west.

About 1822 the Water Lane side of the premises was renamed the Sussex Hotel, but the Bolt in Tun continued as the booking office and coach destination in Fleet Street. You could still get a drink there: in 1830, John Richardson, 38, was nabbed by a police officer in the Bolt-in-Tun tap for stealing a horse-blanket worth eight shillings from the Bolt-in-Tun’s stables. (His defence was that “I was very tipsy”: he was fined one shilling and discharged.) The stables still had a hayloft, of course, and in March 1838 a fire broke out in the Bolt-in-Tun hayloft which “extended its ravages with great rapidity”, destroying all the hay, while the adjoining house, “occupied by many poor families,” was also “considerably damaged”. The proprietor in charge of coaching operations was Robert Gray, whose partner was Moses Pickwick – a surname that a young Fleet Street reporter called Dickens found a use for.

The coaching era, however, was nearing its end. From 1838 onwards, London was increasingly connected to the rest of Britain by railways, and in the 1840s the Bolt-in-Tun was described by its proprietor as a “Mail, Coach, and Railway Establishment”. Gradually the railway side took over, and by 1859 the Bolt-in-Tun was purely a booking office and parcel collection point for the railway companies. Eventually, in late 1882 or early 1883, most of the Bolt-in-Tun was demolished, ending a history of more than 440 years.

Timothy Richards and James Stevens Curl, authors of City of London Pubs, published in 1973, thoroughly screwed up the history of the Bolt-in-Tun, completely confusing it with the Tipperary, and claiming that “shortly after 1883 the Irish house of Mooney erected a new pub on the site of the Bolt-in-Tun, and it is this building that now stands.” This is, of course, as egregiously wrong as anything on the Tipperary’s signboard. Mr Curl is an extremely distinguished architectural historian, a member of the Royal Irish Academy, a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London, a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Chartered Architects of the City of London. He is a Professor at the School of Architecture and Design, Ulster University, Professor Emeritus at De Montfort University, Leicester, and a former Visiting Fellow at Peterhouse, Cambridge. He has written more than 30 books. Let us say that the entry on the Tipperary in City of London Pubs was not his finest hour.

The Boar’s Head led a comparatively quiet life compared to its neighbour. Boar’s Head Alley, alongside the pub, is first mentioned in 1570, and two inhabitants of the alley had to appear at a ward inquest in 1595 for not having chimneys in their houses. The first known licensee was William Hayley or Healey, there in 1664 and 1665. The next year the pub was destroyed in the Great Fire, but Hayley was back in business within a couple of years, and issuing a trade token bearing the words “William Healey at the [picture of a boar’s head] in Fleet Street • 1668 • His Halfe Penny”. How much of today’s pub dates from the post-Great Fire rebuilding I don’t know, but the City of London’s own “Fleet Street Conservation Area Character Summary and Management Strategy” paper from February 2016 named it as one of only “a handful of survivors immediately post-Great Fire” in the conservation area. The report dated the pub building to “circa 1667”, saying that the “slightly crooked window details” hint at its age, and adding that it has a “later, traditional pub frontage and stuccoed upper floors on a narrow historic plot.”

Behind the Boar’s Head, the rectangle of land bounded by the Thames, the walls of the Temple, Fleet Street and Water Lane/Whitefriars Street was known in the 17th century as “Alsatia”. It still had some of the privileges of sanctuary left behind from the days when it was the site of the Carmelites’ friary, which privileges were confirmed and enlarged by a royal charter issued by James I in 1608. The rule of law thus did not run in “Alsatia” as firmly as it did in the rest of the city, so that it was a refuge for on-the-run debtors, and “a hiding-place to cheats, false witnesses, forgers, highwaymen and other loose characters who have openly resisted the execution of legal process”, until the privileges of the liberty of Whitefriars were extinguished by William III in 1697.

The district continued to be lively. The Boar’s Head had all its windows smashed by a Jacobite mob during the “mug house” riots of 1716, because the landlord, Mr Gosling, was “well-affected to his Majesty King George and the present Government.” (It was described in news reports as an “ale house”, putting it one rung down the ladder from an inn like the Bolt in Tun.) Gosling was lucky: the mob’s real target was Mrs Read’s Coffee House in Salisbury Court, the next street east from Water Lane, which was a centre of Whiggish support for Britain’s new Hanoverian ruler. The Jacobite supporters stormed the coffee house, and when the landlady’s husband, Robert Read, shot dead the leader of the rioters, Daniel Vaughan, they smashed their way in, mad with fury. While Read and some of the coffee house clients escaped “with some difficulty” out the back, and others sheltered behind a barricade on an upper floor, the rioters trashed the downstairs rooms, smashing all the furniture to sticks and drinking all the ale, or letting it pour onto the floor. The Sheriff came and read the Riot Act, passed only the year before, and when that failed to have any effect, mounted troops were called in. The tumult finally ceased, arrests were made, and five rioters were later hanged in Fleet Street opposite Salisbury Court. Read, meanwhile, was found not guilty of Vaughan’s murder. You don’t get THAT kind of thing happening in Starbucks …

Gosling and the Boar’s Head were given a page in Ned Ward’s rhyming pub guide to London, A Vade Mecum for Malt Worms, written around the same as the mug house riots. This makes the Tipperary today one of the few among the 200-plus pubs Ward wrote about in the Vade Mecum and its companion, the Guide for Malt Worms that are still open. Ward described the Boar’s Head’s landlord as “justly prais’d/and by his Courage and good Drink emblaz’d/Is to some height of reputation rais’d.”

He had a better reputation than a later landlady. In 1775 there was a complaint by the wardmote inquest against Sarah Fortescue, widow and victualler of the Boar’s Head alehouse in Fleet Street, for keeping her house open at unseasonable hours, frequently the greatest part of the night, and for harbouring and entertaining “lewd women and other infamous and disorderly persons to the great disquietude and disturbance of her neighbours.”

Some time after the premises had risen from mere alehouse status: in 1812 the Boar’s Head was described as “That well known and long established first rate Wine Vault and Liquor Shop,” brick-built, four storeys high, and in the occupation and on lease to Mrs Geary at “the very low rent of 50£ per annum.”

The Boar’s Head survived the demolition of its neighbour, the Bolt-in-Tun, and then became the fourth of the Mooney’s Irish House chain in London in 1895, four years after the death of JG Mooney himself (the company continued under his sons Gerald and John Joseph, the latter a nationalist MP and, in 1900, the youngest member of the House of Commons.) The Mooneys brought in an English architect, RL Cox, to refurbish the pub, and it was presumably under his direction that the mosaic floor was put in, and the front step installed that still says “Mooney’s”. A fifth pub, near Piccadilly, was bought in 1896. The original premises in the Strand were closed when Kingsway was built, but a new bar was opened at 395 The Strand in 1900 which, until it shut around 1967, was famed for having the longest bar in London. At one point the company had another pub in Fleet Street, at No 154, formerly the Portugal, which closed in 1910. The serving staff in all its pubs were all male and Irish – no barmaids, apart, apparently from a brief experiment around 1963 – and Mooney’s Irish Houses were known for excellent service, excellent prices and excellent food.

Through the 1960s the company began to retreat from London, with the former Boar’s Head disposed of in about 1966-67, which is when the name change from Mooney’s Irish House to The Tipperary looks to have taken place. At the same time the name The Boar’s Head seems to have been resurrected for the upstairs dining room, as indicated on the signboard outside the pub: I am sure I can remember that the name “The Boar’s Head” used to be visible between first and second-floor level on the pub’s fascia in the 1980s or 1990s. Greene King is supposed to have taken the pub over in the 1960s: I haven’t researched this particularly, but the 1979 Camra “real beer in London” guide shows the Tipperary selling Everard’s Tiger and Wethered’s bitter, which suggests this is as inaccurate as the rest of the signboard’s claims about the pub. It apparently closed for a couple of years around the start of the 1980s, I believe, for a refurbishment, and it was certainly a Greene King pub in 1986, when it was listed for the ’87 Good Beer Guide as selling IPA, Abbot and the much-missed (by me) Rayment’s BBA. I am middlingly sure I drank Rayments in the Tipperary about that time, since I would have hunted out a rare central London outlet for one of my favourite beers, though that was 32 years ago. GK looks to have sold the pub a few years back, and it is now under independent ownership.

That’s it: a vastly, vastly more accurate history of one of London’s oldest pubs than you will find anywhere. What are the chances of promoting the correct version of events over the one on the signboard? Not good, I fear: there are at least five books, a number of newspaper and magazine articles (including one from the Daily Mirror which was, again, wrong in every sentence) and dozens of websites repeating the total nonsense version, including one book published a couple of years ago that talks of “the famous Dublin brewer SG Mooney & Sons” – they can’t be that “famous”, mate, you’ve never heard of them before, because THEY DON’T BLAHDY EXIST. And the more observant of you will have spotted that this particular author can’t even copy inaccuracy accurately: the signboard outside the Tipperary says “& Son”, not “& Sons”.

(Astonishingly, should you have £46 to throw away, you can buy a Tipperary pub Christmas decoration, 7.5cm high, to hang on your tree – down from £82, apparently.)

Great take-down of inaccuracy and grammatical/typographical error. Particularly apposite for the location, as you say. Such a shame, then, that you include: “but it is NOTING to do with returning printers…”

Or was that deliberate? 😉

No, it was a typo, which I’m happy to say I spotted and corrected BEFORE seeing your message (honest, guv).

Cracking research as always and a fascinating view into the City’s past.

Nice one, though possibly a bit unfair on the rats. Recent research indicates that they couldn’t spread plague as fast as it went and the fleas more likely travelled human-to-human.

The Parnell Mooney on Parnell Street was, I think, the last vestige of the former Mooney chain in Dublin. It was rebranded as simply “The Parnell” about ten years ago. The Grafton Mooney is now Bruxelles and The Baggot Mooney is a bank. In Ulysses, Joyce refers to “Mooney’s en ville” and “Mooney’s sur mer”, meaning the Abbey Street and Eden Quay branches, respectively. Both were destroyed in the 1916 Rising.

Disused pub becomes a bank? O tempora! O mores!

I first went there in the late 70s and worked nearby from 82. While an Irish bar the bitter was certainly Everard’s Tiger. The hand pumps were downstairs (street level), but if you went upstairs they’d order down and bring them up a dumb waiter

This excellent article inspired me to create a Wikipedia page for the New Hall Inn, otherwise known as the Hole in t’Wall at Bowness on Windermere.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Hall_Inn

Not for want of trying, but I didn’t do quite as good a job as you Martyn!

Mr. Cornell–

You may not be interested in this, it doesn’t really affect anything you’ve written regarding the Tipperary, but I have for several years, off and on, researched what I assume to be the first ever London pub guide: The Vade Mecum for Malt-Worms, etc. (c 1715). I had over the years found three pubs mentioned in that book still in existence: The Ship Inn behind Holborn Station, the Magpie & Stump at 18 Old Bailey, and, as you noted, the Tipperary, nee the Boar’s Head. There may be others, but my time for pursuit is spotty and the author of “Vade Mecum”, whomever he was, wasn’t as helpful with addresses as one might wish.

You no doubt note, I’ve questioned the authorship of the Vade Mecum. As you say, do a little research and you might learn something. Three or four years ago I came upon a book published in 1946 by Harvard University Press, NED WARD OF GRUB STREET by Howard William Troyer. Troyer only makes mention of the Vade Mecum in the back pages, a detailed timeline of published works by, and citing, Ned Ward. It is his thought that Ward had nothing to do with the writing of the Vade Mecum and that it is actually the work of several writers. I’d cite chapter and verse, but I am in London just now and the book is cozy and warm on a shelf in my den in the States.

Thank you: I note that Google Books won’t let one see the relevant part of Mr Troyer’s book, but it’s available quite cheaply through ABE Books, so I have ordered a copy … a fourth still-open pub is the Flying Horse in Moorgate.

I won’t ruin it for you. Just say that it’s on page 281. And Troyer gives the date of the “Vade Mecum” publication to be around 1720, five years or so after most estimates.

Thank you for your continuing marvelous posts

Well done for clearing that up. Sadly, you made an error yourself. “The Fire of London the following year at least cleansed the city of plague-carrying rats” just isn’t true. if you consider the areas where the highest proportion of the population died in the Plague, none of them were touched by the Fire. Not St Giles Cripplegate, not St Giles in the Fields, not St Botolph Aldgate, none of the Borough. Still, all credit to you for the rest of the research. Some friends and I visited every pub in the Square Mile a few years back, the Tipperary included. We enjoyed the beer, but noted that in common with most pubs, their research was decidedly iffy. I did some research on the Hoop and Grapes on Farringdon Road, and found that it’s probably the last building still standing that faced the Fleet River. Enjoy the pubs – I live in Portugal nowadays and the piss that deputises for beer here isn’t worth the name.

Right – so that was why the plague continued to rage after the Great Fire. No, wait …

You’re right that the Plague happened then the Fire, and that the Plague never returned after the Fire. And it’s too easy to assume that the latter destroyed the former, but it’s simply not the case. In fact nobody knows why the Plague never returned to London, but we do know that the areas most affected by the Plague were untouched by the Fire. We also know from population records that after the Plague and the Fire those areas remained just as densely populated as before, just as unsanitary. You can find maps with the density of fatalities and compare them to maps of where the Fire destroyed if you don’t believe me. I don’t mind either way.

[…] The Tipperary – Grade II listed too (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1251734), but, apparently, nowhere near as historical as it claims to be: https://zythophile.co.uk/2018/09/27/the-tipperary-fleet-street-its-a-long-long-way-from-accurate-hist… […]

A little aside — the song “It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary” had absolutely nothing to do with the Great War. It was composed and first recorded in 1912 – two full years before the war started. I collect records from that period and have a copy, with all the original verses (this one sung by Albert Farrington). The song is about an Irishman marooned in London writing to his sweetheart whom he misses terribly. Very peaceful. No trenches, guns, bombs, etc. There are endless recordings of it made by different singers of the time after it became “adopted” by the soldiers, the most popular of which is by John McCormack recorded in 1914.

I lived in Mooney’s Fleet Street, and prior to that Mooney’s in The Strand. My dad was the publican, Dermot Gray, living in the flats above Mooney’s pubs. I moved in months old and moved out of Fleet Street in 1966 shortly after dad’s death aged 11. The pub was never called The Tipperary and always Mooney’s Fleet Street. There was another at London Bridge. All were popular but all sold in the later 1960s.

[…] tendency of pubs to tell outright fibs about this kind of thing. It turns out that many such claims can be dismantled with a bit of work and you soon learn to ignore any information board that opens with it “It is […]

[…] hyviä, koska niiden mukaan vanhin on Lontoon Fleet Streetin The Tipperary -pubi (vuodelta 1700). Martyn Cornell on todistanut, että kyseisestä keskiaikaisesta pubista tuli “irlantilainen pubi”, Mooney’s Irish House, […]

Another little snippet to add to your store!

George Paul LLD, who was Vicar General of Canterbury and later the Kings Advocate, says in his Will proved in 1775:

“I give devise and bequeath all my Estate in Fleet Street consisting of houses in Johnsons Court & Boarshead Court the Bolt and Tun Inn Bolt and Tunn Passage to my dear Wife with all the Right property I enjoy in them ………..”

Spelling and lack of punctuation are correct!

Georgina

Dear Martyn,

In your very interesting blog you describe how Moony bought the lease to No 66 that was described in 1812 as “a long established first rate Wine Vault and Wine (SHOP) so not a pub. Could it therefore be that Moony used the name of the former pub on the next premises on the corner of Water Lane/ White Friars that burnt down in 1666 to merge the history and identity of former pub the Boars Head with their premises. Can you explain to me where the 1812 quote came from ? as this would be most helpful to me.

The 1812 quote is from an advertisement in the Morning Chronicle, Saturday June 6 1812, p4. Mooney’s only ever called the pub Mooney’s Irish Bar.

Thank you Martyn, I’m very grateful to you.

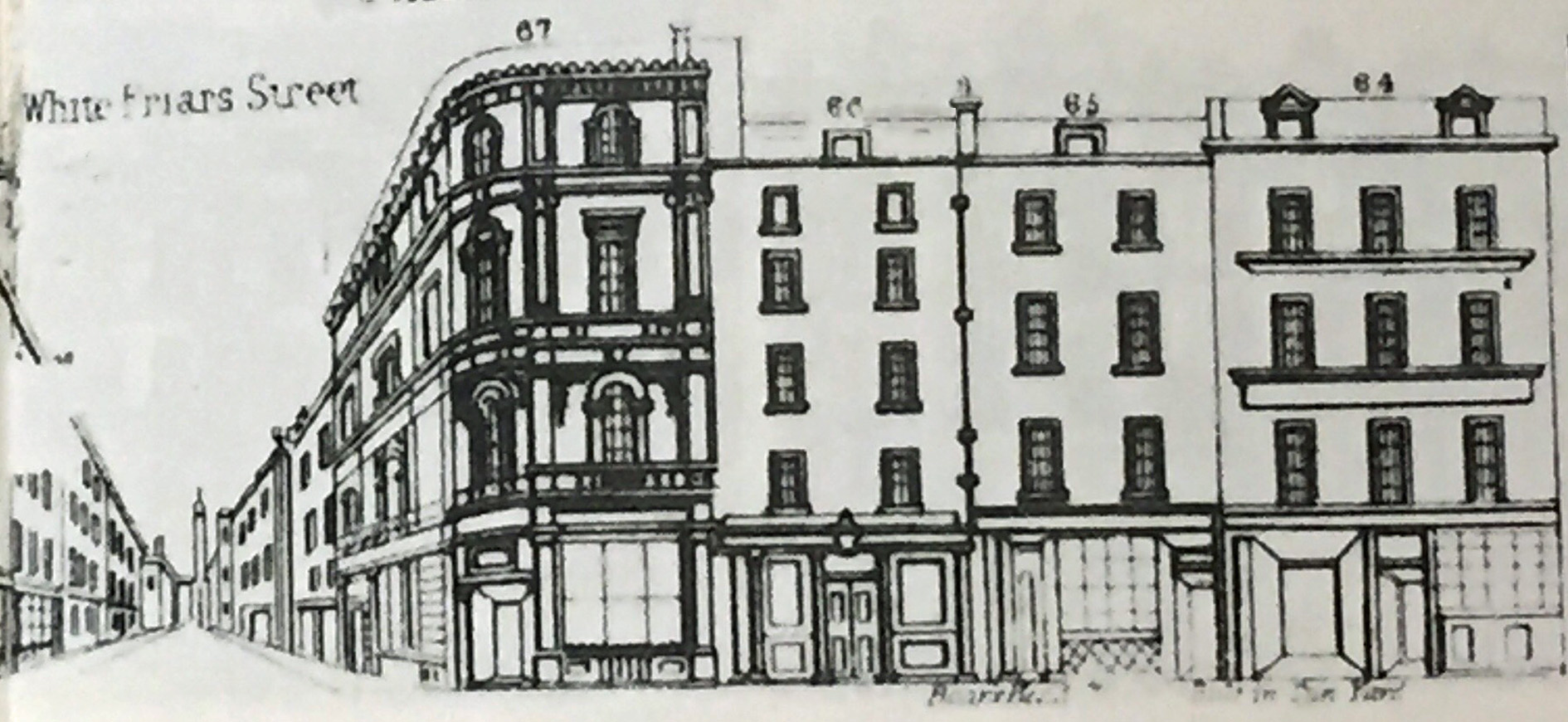

Clearly the Tipperary premises No 66 were spared demolition for a very special reason since all the remaining premises in the terrace between WhiteFriars Lane and Bouvery Street had suffered this despite their lineage. The new radiused corner property next door on the corner of today White Friars Street therefore must have been erected in the 19th century to support the very old ‘Party Wall’ at no 66 which was probably originally on the corner of WhiteFriars/Water Lane. Subsequently White Friars/ Water lane would have been moved slightly Eastwards. The only reason the Council would save this building would be if someone very famous had been associated with it, so probably not because Moony’s had moved to the site, but maybe someone buried in Westminster Abbey who was granted this special privilege ?

Your blog has certainly opened up new possibilities.

Regards,

Bren Calver..

Martyn,

Just one final question. Did you find any evidence to support the ‘Boars Head’ being spared demolition, since as the account in the 1812 Morning Chronicle stated the Boars Head had 4 floors but, clearly today as the Tipparary it has only 3? Could it be todays No 66 was actually No 67 on the corner that did have 3 floors. It seems from later street scene’s to have had a modern 19th century building erected against its outside wall to make it a Party Wall for safety, with the new building facing onto White Friars Street? There had to be a reason why this building got spared when 4 got demolished.

Regards

Bren.

No, I never explored the site history that deeply. Far too m uch else on my plate, alas …

What you have already done in the time you have is a really good effort which others I note also appreciate too. On the matter of post 1895 I raised as to what building actually got reprieved from demolition I suspect we will never know since records have probably perished through flood, fire, and neglect, otherwise someone would have researched them by now with the answer. The assumption has been it was no 67 but that belonged to a famoue clockmaker therefore it could hasve been No 66 and street numbers shunned eastwards as old WaterLane was to become renamed WhiteFriars Street again. It is amazing when 4 buildings of equal importance historically got destroyed, someone decided to save this one.. Therefore there must have been a very special reason since it wasn’t a pub then but a wine and licquer shop. Thanks for the interesting read good drinking!

Following on from my comments on 27 April, this may also be useful. Dr George Paul’s wife Susanna died two years later in 1757 and her Will states:

“I give devise and bequeath unto the beforementioned Doctor Edward Simpson and Edward Rushworth (the Trustees) All those twelve freehold Messuages or Tenaments situate and being in Johnson’s Court in Fleet Street London with the Appertenances And also all that freehold Messuage Tenament or Inn called the Bolt and Tunn in Fleet Street London And all those five freehold Messuages or Tenaments near thereto adjoining situate in a certain Court called Bolt and Tunn Court And all those four other freehold messuages or Tenaments situate in Boarshead Court near the Said Bolt and Tunn Inn And also all that Leasehold Messuage or Tenament and Ground situate on the West side of the said Inn …..”

The Will goes on to say that various properties including these are to be sold to give an annuity to her son. Interestingly, one of the executors of the Will was Robert Snow, her son-in-law, who was part of the Snow bank a little further west at 217 Strand. Robert Snow was married to Margaret Strahan, a granddaughter of William Strahan the printer of Little New Street, close to Johnson’s Court, who was known to drink in the Mitre!

Dear Martyn,

Has the Tipparay got a cellar since looking at outside photos there doesnt appear trap doors to one. Maybe there is storage at the rear of the pub. Its important since I’ve seen documents that suggest it doesn’t.

Hi Martyn,

Just under the Shamrock picture three paragraph’s down there an interesting extract from somewhere about Mr Geary that describes her Licquer shop at the Boars Head. Was this from an old Chronical?

Bren.

Georgina,

Forgive me interjecting in a conversation with Martyn and my apologies to Martyn also but, you say “George Paul LLD, who was Vicar General of Canterbury and later the Kings Advocate, had his Will proved in 1775” and then his wife died two years later in 1757 left the Boars Head tenements for sale and the proceeds for her son? Are these dates correct and it took 18 years to prove his Will? Have I missed a communication since.

Bren

I’m sorry it has taken so long to reply! I’m afraid it was a typo, my mistake! George Paul died in 1755 and his wife Susanna 2 years later in 1757. Sorry about that. I see I mis-stated it in my comment of April last year as well, so I must have picked up the date from that comment rather than his actual Will. How awful of me to leave an inaccuracy on Martyn’s excellent site which is all about accurate reporting!

Georgina

[…] draught – and could also lay claim to being the narrowest in London. (London Remembers and Zythophile have debunked most of these claims, […]

I was visited Mooney Irish Bar while I was stationed in England in 1963-64. I spoke with a Mooney who was, as I remember, an owner and treated to a pint, I was. That bar was the longest bar I had ever seen….I mean LONG! Am returning in Aug.’23 and plan to visit the premises again, 60 years later. Should be interesting……And thank you for your research.

I fear you’ll find it’s long vanished, Thomas. It was Mooney’s on the Strand that you visited, and I believe the site is now occupied by a shop for stamp collectors.

pardon the typo……I visited.

[…] the history of the pub, which is, as I pointed out six years ago, wildly inaccurate in every book and article that mentions the pub, has become even more muddied. […]