The canard that brewers in London did not brew with water from the Thames because the river was, supposedly, full of sewage and dead dogs quacked up on Beer Twitter last week, so I thought it would be useful to run an extract from the (long-overdue) Great Porter History Book to try to squash this particular myth forever: London brewers were still using Thames water until the middle of the 19th century. I’ve included the footnotes, for once, in case any scholar wants to copy this.

Supplies of potable water were always a problem as London’s population grew, and the brewing industry needed considerable quantities of water to malt and mash with. The Thames was one resource, of course, and despite the mythology that surrounds the river’s historic alleged unwholesomeness, brewers made use of its water to brew their beer for centuries: In 1509 the Bishop of Winchester (who owned considerable land alongside the river in Southwark – much of it occupied by brothels[1]) and the Priory of St Mary Overies granted a license to the brewers of Southwark to have passage with their carts “from ye Borough of Southwark until the Themmys … to fetch water … to brew with,” so long as the brewers did not try to claim the passage as a highway, a license renewed by later bishops[2]. (The Thames at Southwark is surprisingly shallow at low tide, and horse-drawn carts could be driven some way out into the stream to collect water in casks.)

Early in the 17th century, a hundred years later, brewers in St Giles Without Cripplegate parish, on the northern edge of the City of London, which covered an area including Chiswell Street, Whitecross Street, Golden Lane and Old Street, were carrying water in carts three quarters of a mile from the Dowgate sluice on the banks of the Thames to their brewhouses to make their beer and ale with[3]. As more and more water was required, this method of collecting it became inadequate. In 1617, led by a brewer named George Beale of the Crown brewhouse in Red Cross Street, the brewers in the parish petitioned the City of London to be allowed to lease the waterhouse at Dowgate, and run pipes all the way to their breweries. The City agreed, though there was some pressure from the Royal court to make the brewers use the water from the “new stream” that had just been built by Hugh Myddleton to bring water from Hertfordshire to London: the scheme had been part-funded by King James I in return for a share of the profits, and the king did not want his income from selling water undercut by people getting suppliers from elsewhere. In the end the brewers had to agree to “take in Myddleton’s water for their other uses, and to pay reasonable rents for the same.”[4]

The brewers of St Giles Without Cripplegate, who would eventually include such porter giants as Samuel Whitbread and John Calvert (whose Peacock brewery took over the Crown brewery and used it as a store), doubtless eventually stopped using Dowgate Sluice water entirely in favor of Hugh Myddleton’s New River supply. The building of the New River, opened in 1613 to bring water from springs in Great Amwell, Hertfordshire to a reservoir at New River Head in Finsbury, North London[5], 18 miles as the London crow flies but 28 miles by the route taken to allow gravity to carry the water from the springs to their destination, which demanded advances in the technology of surveying and canal-digging, resulted in a considerable number of big London brewers brewing with water ultimately sourced in Hertfordshire.

The New River Company signed at least one contract with the brewers of London in Charles II’s time, and probably more[6]. The six largest of the New River Company’s customers in 1769 were all big porter brewers: Gyfford & Co of Castle Street, Covent Garden (later Combe Delafield & Co); Truman & Baker of Brick Lane; Samuel Whitbread in Chiswell Street; Calvert’s Peacock Brewhouse in Whitecross Street; Robert Hucks in Hyde Street; and Chase & Cox in Great Russell Street, later Meux. In Covent Garden, Gyfford & Co was using 1.8 million gallons of water a year, almost 5,000 gallons a day, with Whitbread, Truman and Calvert not far behind, and Hucks, and Chase & Cox on just over a million gallons a year. In all, 19 of the water company’s 34 largest customers were brewers, including the Victual Office at Tower Hill, supplier of beer to the Royal Navy, while one was a distiller[7]. The New River springs at Amwell tapped into precisely that semi-hard, calcium carbonate-impregnated water that was most suitable for brewing dark beers. and brewers supplied by the New River produced at least a third of London’s porter[8].

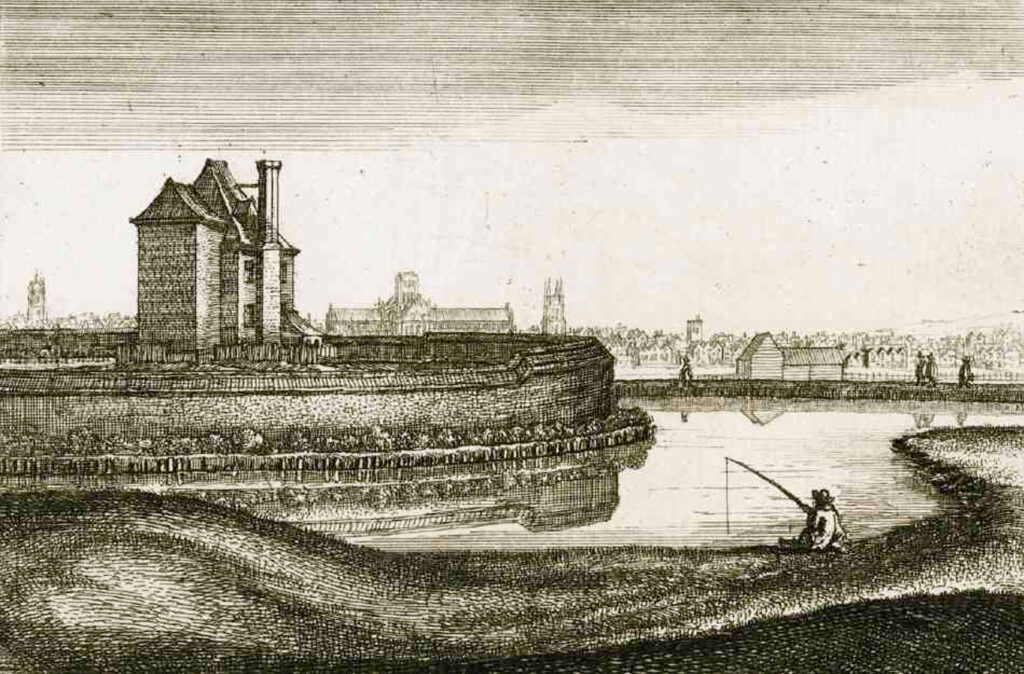

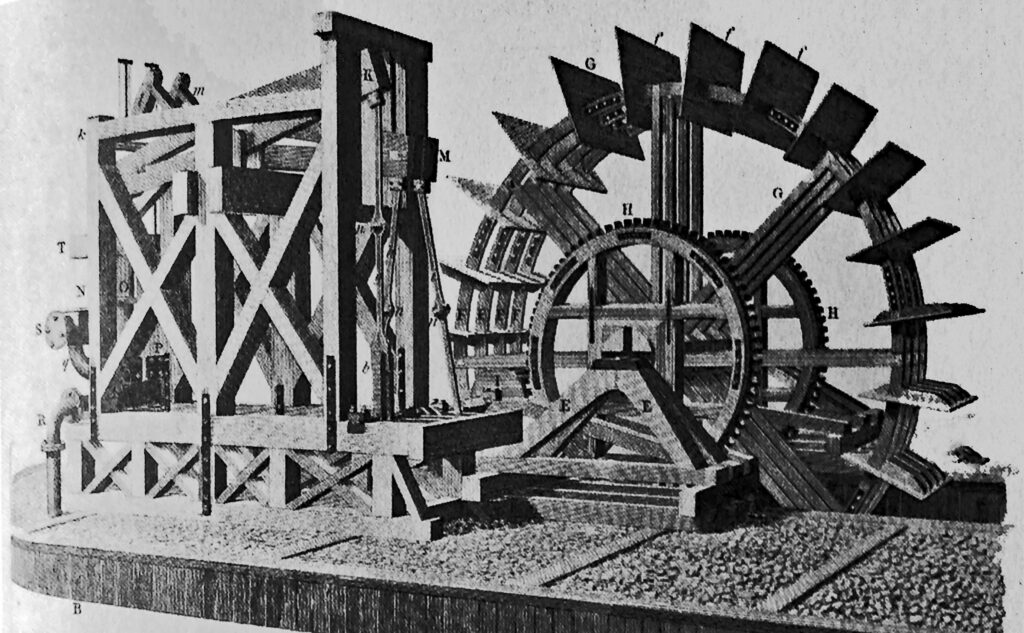

A fair number of London’s porter brewers, in an area stretching from Fleet Street in the west to the Whitechapel Road in the east, and perhaps some in Southwark as well, probably received their water supplies from the London Bridge Water Works, a now almost forgotten engineering marvel that used water wheels in the arches of old London Bridge, powered by the tides, to pump water from the Thames to its customers. The first waterwheel-powered pumps had been installed under the northernmost of the bridge’s 19 or so arches in 1582 by an engineer from continental Europe called, variously, Peter Morris, Morice or Moritz (sources differ on whether he was German or Dutch) using technology developed in Germany[9]. It ran for another 240 years, surviving the Great Fire of London in 1666, constantly updating its pumping technology, until 1822, when the City of London Corporation decided to rebuild London Bridge without the waterworks, and the London Bridge Water Works’ network was taken over by the larger New River Water Company[10].

At least one brewer found a private way to tap the Thames: Henry Thrale, the big porter brewer of the Anchor brewery in Southwark (later Barclay Perkins), had a waterworks built at Bankside in 1763 to pump water to his brewery, with the pumps operated by horses, until he sold it to the Borough Water-Works company, which installed a steam engine about 1770 to work the pumps[11].

The best answer to water shortages, though, lay below brewers’ feet: wells had been dug in London from the Roman era[12], though the first deep wells do not appear to have been dug through the London Clay into the underlying water-bearing sands until the late 1780s[13]. But as well-digging technology improved, so did the ability of London’s brewers to tap sufficient water hundreds of feet down to keep up with demand for their ales and beers. Whitbread in Chiswell Street had a deep well by 1810, which evidently tapped a widely linked source: when “much” water was drawn from Whitbread’s well, a well failed at St Bartholomew’s hospital, 750 yards away, and vice-versa[14]. Even the Thames-side brewers eventually used deep well-water, though it was discovered that when Calvert’s Hour Glass brewery on Upper Thames Street in the City was pumping water from its well, the level of water went down in the well at Barclay Perkins in Southwark on the opposite bank of the Thames: both were tapping into the same water-bearing stratum, which ran under the river[15].

All the same, it was written in 1839 that four London porter brewers were still using Thames water to make their beer, though that represented “not a sixth part” of the total production of porter in the capital, and “the breweries have in most cases private wells.”[16]

[1] E. J. Burford, The Bishop’s Brothels, London, England, 1993, p38

[2] Sir Howard Roberts and Walter H. Godfrey (eds), Survey of London, Volume XXII: Bankside, London County Council, England, 1950, p78.

[3] London Metropolitan Archives City Lands Estates ref CLA/008/EM/02/01/002/009v/03

[4] W. H. and H. C. Overall, Analytical Index to the Series of Records Known as the Remembrancia A. D. 1579-1664, London, England, 1878, pp557-8

[5] Leslie Tomory, The History of the London Water Industry 1580-1820, Johns Hopkins University Press, Maryland, 2017, p54

[6] John R. Krenzke, Change is Brewing: The Industrialization of the London Beer-Brewing Trade, 1400-1750, PhD dissertation, Loyola University, Chicago, Illinois, 2014, p126

[7] Tomory, p190

[8] Ibid., p200

[9] Ibid., p32

[10] Ibid., p237

[11] Matthew Concane and Aaron Morgan, The History and Antiquities of the Parish of St. Saviour’s, Southwark, London, 1795, pp49 and 234

[12] Roger S.O. Tomlin, Roman London’s First Voices, Museum of London Archaeology, England, 2016, p9

[13] Edward P.F. Rose and J.D. Mather, eds, Military Aspects of Hydrogeology, London, England, 2012, p43

[14] John Wallis, London: Being a Complete Guide to the British Capital, London, England, 1810, pp265-6

[15] The Repertory of Patent Inventions, London, England, new series vol IV, no XIX,July 1835, pp42-3

[16] Chambers Edinburgh Journal, quoted in The Museum of Foreign Literature, Science and Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, vol 35, February 1839, p261

Fanatastic article, as ever. One tiny niggle, though (and apologies for the pedantry). I thought this was a UK blog, yet you say “the Priory of St Mary Overies granted a license to the brewers of Southwark…”. I would have thought that it as a “licence” that was granted – a word which is rapidly disappearing from UK English today but was in use in 1509.

That whole blogpost was copied-and-pasted from a book I am writing for an American publisher, hence the American spelling of licence. I ought to alter it to BrE spelling, but I CBA, frankly …

Understood! And forgiven.

Great article. I read many moons ago that Porter was made dark because it made it easier to hide the use of “not ideal water”. Always wondered if that true?

No, that would be a myth, I’m afraid.

How did the Anchor Brewery by St. Luke’s Church in Chelsea, Britten Street, get it’s water? Was there a well, and if so what happened to it?

Is there any way of finding out?

I would really like to know

Try looking at old large-scale Ordnance Survey maps, which may plot wells.