Descriptions of London’s big porter breweries in the 19th century by an actual brewer are exceedingly rare. One of the few such reports was made by a young Canadian named William Helliwell, who visited four of the capital’s big breweries in the summer of 1832, and left his impressions in a diary.

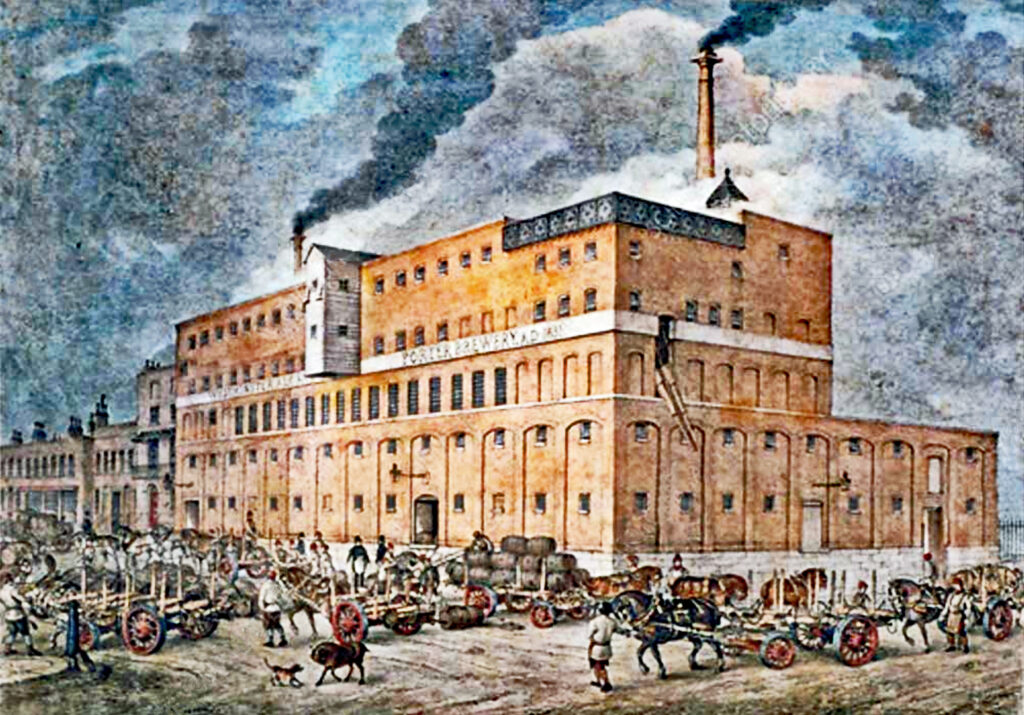

William’s father, Thomas Helliwell, had come to Canada in 1818 with his family from Tormorden, on the Lancashire-Yorkshire border. Thomas Helliwell set up a distillery in Niagara before moving to what is today called Toronto and was then still called York in 1820, settling by the banks of the Don river, some four miles from York, and building the Don Brewery. Thomas died in 1825, and the business was carried on by his widow Sarah and their sons. After Sarah retired, the business continued, ostensibly under the name of the eldest son, Thomas junior, as Thomas Helliwell & Brothers. Thomas had other business interests, and most of the responsibility for the brewery devolved onto William, the third son, born 1811. He became a partner in the business in 1832, when he was 21, and was immediately sent to England to study the operations of the great breweries of London.

William seems to have seized every chance to look round breweries on his journey: he visited two in Rochester, New York state and two more in nearby Albany on his way to New York to catch a ship to England, where he arrived in mid-June after a six-week journey from Canada. In London he had an introduction to Timothy Thorne, owner of the Westminster Brewery on Horseferry Road, from Thorne’s son Charles, whom William knew in York. The brewery, which made ale and porter, had been founded by Timothy Thorne in 1826. (It was eventually acquired in 1914 by the Lion Brewery across the river: another branch of the Thorne family ran a brewery at Nine Elms, Battersea that was bought by Meux’s of Tottenham Court Road, who moved their operations to Nine Elms in 1921.)

William’s diary did not record any details of his trip round Thorne’s premises. However, he left the world fascinating glimpses of three other big London breweries he visited, Calvert’s, in Thames Street, Elliott’s in Pimlico (later Watney’s) and Barclay Perkins, in Southwark.

At Calvert’s, which sat hard by the Thames next door to Charing Cross station, he was shown first round the porter brewery, with sights including a mash tun 30 feet in diameter and eight feet deep, which held 120 quarters of malt, some 19 tons of grain. Of the two coppers, the largest held 1,200 barrels, and included a mechanical rouser, operated by steam, that prevented the hops from settling to the bottom. Brewing water was held in a cast-iron reservoir at the top of the brewery “as large as a quarter-acre field,” that is, perhaps 120 feet long by 90 feet wide. There were four coolers, each 126 feet by 20 feet, and fermenting tuns “like little houses, being built square, with doors in at the side.” The beer was “worked off,” that is, finished fermentation, in round casks that held four butts, 532 gallons, each. When that process was complete the porter was then pumped into a common square, where it remained for a few hours to settle before being transferred into storage vats.

The brewery held 11 vats, eight 36 feet high and 15 in diameter, each held together by 24 hoops, and two 40 feet high and 20 in diameter, which could hold a week’s worth of brewings, according to William (although the maths does not look to support this). He was also shown the malt bins, 12 in number, 30 feet wide and 15 square, and the yeast reservoir, made of stone, sunk into the ground, and measuring ten feet square and six deep, which would have held around 3,500 gallons of yeast.

William next went through the stables, where he saw “about 20 Hosses like elephants” (spelling was not one of his strengths), and was told that the brewery owned some 70 horses in total. After that he was taken to see Calvert’s new ale brewery, built “on the most improoved plan & verey extensive.” This was not yet two years after the passing of the Beer House Act in England, which had led to more than 30,000 new beerhouses openings, and most of the big London porter brewers, of which Calvert’s was one, had started brewing ale as well as porter to supply these new outlets. Ale brewing looks to have been conducted with considerably more attention paid to hygiene: William commented that “I could not help remarking the vast differance which appeared in these two conserns with regard to cleenleness in the Porter brewery they appeared to pay no attention to it at all but in the Ale Brewery everey thing was as cleen as Parlors.”

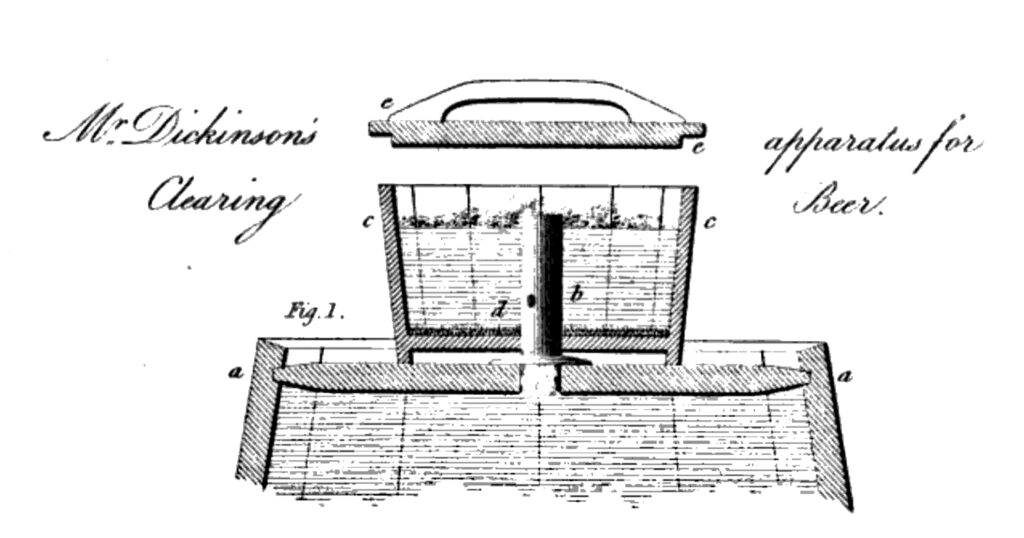

He also recorded the “casks of curious contrivance of pipes” that the ale was worked off in. According to William’s slightly confused description, the casks “allways remain full for as the work out it runs into supply the loss.” This is clearly one of the precursors to the Burton Union system that appeared in the 1820s and early 1830s, designed to automate the topping up of casks of fermenting beer. It was possibly the apparatus for which Robert Dickinson of the Albany brewery in Camberwell, South London won the Large Silver Medal of the Society of Arts in 1824, where a tub sat on top of each cask of fermenting wort, connected to it by a pewter pipe, up and out the top of which flowed the excess yeast and down which, through a hole in the side, flowed replacement wort. However, the major unusual visual component of Dickinson’s apparatus would have been the tub, which William did not mention, suggesting he saw someone else’s apparatus.

The next day, a Friday, William visited Elliott’s Stag brewery in Pimlico, close to Buckingham Palace, another of the big London porter brewers. There he saw a vat room with 27 vats ranging in size from 400 butts to 1,200 butts, or 3,600 barrels. The porter was fermented in rounds, and then run into a large stone “resevoy” (reservoir) to settle, before being pumped into the store vats. The vats, William wrote, were cooled by a “Frigerator.” The brewery employed 260 men, had two steam engines, and 160 horses.

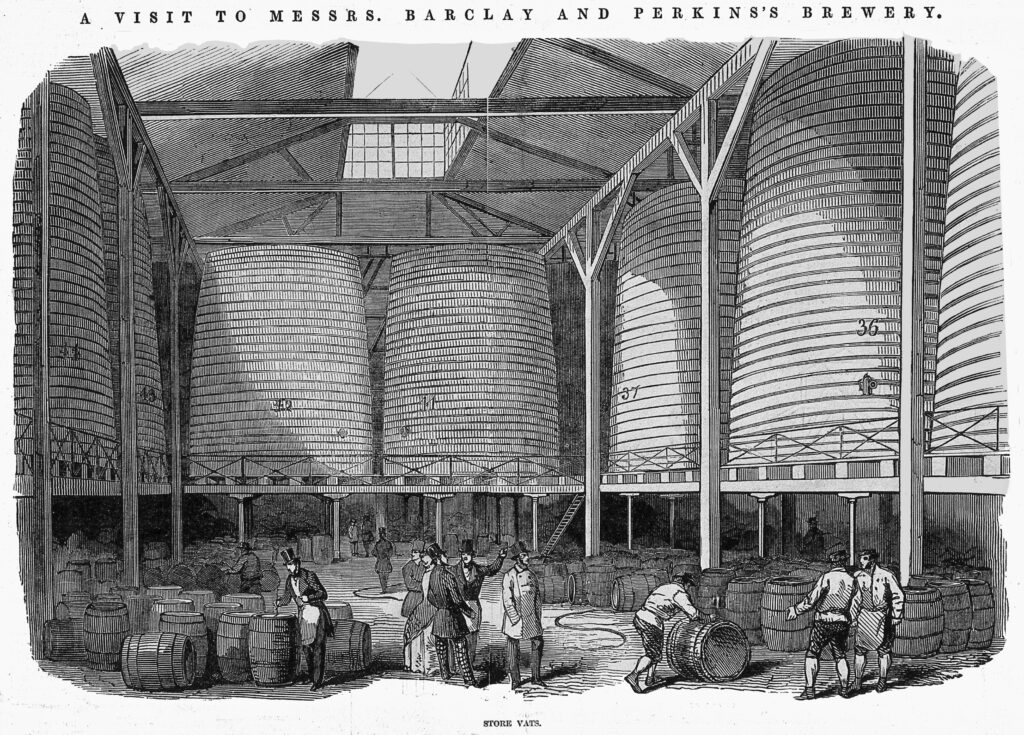

Finally William finished his London brewery tour with a trip on Saturday to the biggest of all, Barclay Perkins, in Park Street, Southwark. The street outside, and the brewery yard, were “so crouded” (sic) with Barclay’s drays that it was “allmost the labour of a Hercules to win my way through them,” William wrote. The brewery had suffered a devastating fire a month earlier (“extinguished by 200 buts of Poter [sic],” according to William), which caused damage estimated at £100,000, perhaps £9 million today. The clean-up was still continuing, with, William estimated, 200 to 300 men involved in repairing the damage and dismantling wrecked machinery, including pulling to pieces the giant coppers, 20 feet in diameter. The fermenting rooms and vat rooms appear to have been largely unhurt in the fire, and William recorded that there were 120 store vats, most holding 2,000 butts—6,000 barrels—of porter each. He was most impressed by Barclay’s method of steam-cleaning their casks, though he also recorded with awe the numbers employed—three to four hundred—at the brewery, “beyond doubt the most extensive consern in the World it is like a Town itself,” and the large number of partners in the business, 80, “with nearly a million sterling of capitol.”

The next day William left London to visit his relatives in Todmorden, departing from the Spread Eagle in Gracechurch Street on the Red Rover coach at 8:30 in the morning, and travelling “at a rate little Short of the wind it self over roads as smooth and hard as the Bay of York when it is frozen over.” Dinner was at Northampton, tea at “Leister”, and around midnight the coach passed through Burton upon Trent, after 120 miles at an average speed, including stops, of a little under eight miles an hour. At Burslem in the Potteries William changed for the Manchester coach, arriving at noon, where he had a five-hour wait for the coach to Todmorden.

William spent just over five weeks in Todmorden, visiting relatives and being entertained, before taking the coach to Manchester and then the not-yet-two-years-old Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the first inter-city railway in the world (travelling at a heady top speed of a mile in two minutes) to book a ship from Liverpool back to Canada. Just before he left Todmorden he witnessed the celebrations given by the owner of the local cotton mill magnate, and radical politician, John Fielder (whom William called “John Feilding”) to mark the passing of the Reform Act, given royal assent by William IV on June 7 1832, which abolished almost 60 “rotten boroughs”, gave MPs to places such as Manchester and Birmingham, and extended the franchise by some 50 per cent. The festivities included processions with bands and banners, and the serving up to more than 5,000 people of vast quantities of beef “of the best possable quality” and “verey rich Hunters Pudding” (a type of plum pudding), while “the Ale & Porter was excelant and in sufficient quantity.” According to the report in the Preston Chronicle, 15 cows had been killed for the event, with between 300 and 400 puddings cooked, each weighing 7 or 8lb, and 24 barrels of “good brown stout” provided.

In Liverpool William fitted in visits to “two or three small Breerys,” before finding a brig to take him back to Quebec, a journey that took “38 days of the most tedious time that I ever passed in My life” just to get to the Gulf of St Lawrence and another nine to travel the 630 miles to Québec City.

Whether the Don brewery was making porter before William’s trip to England does not seem to be recorded, but it certainly was by 1836: in February 1837 William recorded that he erected a small still “for the purpose of stilling our old ale,” and immediately “ran one still of old Portor [sic].” Porter whiskey – mmmm. In December the same year he “was at home all day Brewing Portor.”

Ten years later, in January 1847, Helliwell Brothers’ brewery and distillery burned down, after a fire that started in the cooling room. The total lost was estimated at £5,000 to £6,000, with insurance cover of only £1,000, and the Helliwells decided, after more than 25 years, not to rebuilt the brewery, concentrating instead on milling and other activities. (Big hat tip to Jordan St John for providing me with a transcript of William Helliwell’s diary.

One of the Barclay Perkins records in the archives is all scorched around the edges as a result of the fire.

I used to think it was the Beer Act that prompted Porter brewers to diversify into Ale. I’m now more inclined to think it was the reform in measures in 1829, when beer and ale casks became the same size.