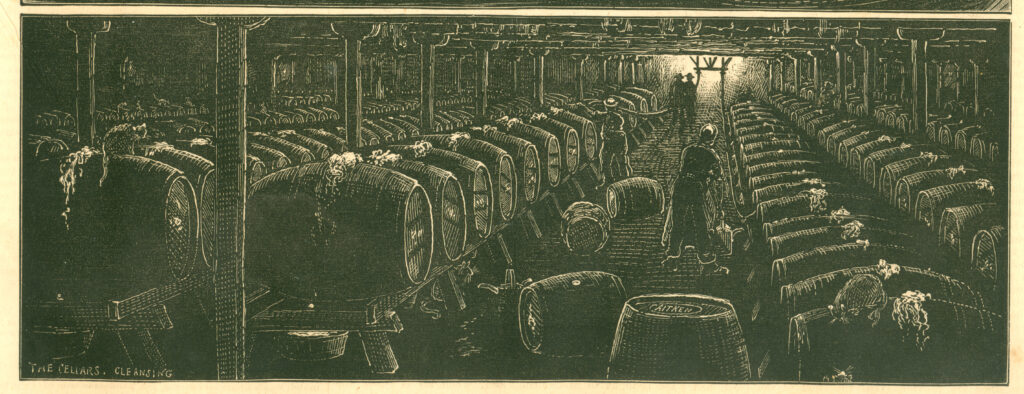

This is a fascinating picture, and not just because of the cats: it depicts the sort of labour-intensive cellar practice that the Burton union system was invented in the 1830s to eliminate, though this engraving dates from 1875. It illustrates the scene in the cellar at Thomas Aitken’s Victoria Parade brewery in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and what it shows is beer undergoing “cleansing”, having been let down from the initial fermenting vessels after two or three days into butts, where the beer will continue fermenting for another four days or so until it is ready for transferring into smaller casks for sending out into trade.

The illustration appeared in a publication called The Australasian Sketcher in April 1875, and the Sketcher‘s writer described the process well:

“After being fermented the liquid is drawn off in pipes to the cleansing butts, that lie in extensive cellars, running all round the building, and here it is known for the first time by the name of beer. These butts form part of the plant of the brewery, and never leave the premises. Between every two cleansers are placed tubs to hold the yeast that oozes up through the bung holes; and, as the yeast works, fresh beer has to be put into the butts to supply its place. After it lies in them till it has ceased to work it is racked off by syphons into ‘travellers’, the technical, and expressive name by which the barrels, with whose sight we are all familiar are known. Every butt has marked upon it in chalk (instrument of writing so freely used in the retail trade of the article) the quality of the beer and the date of the brewing.

“Fixing our eyes searchingly on Mr. Aitken, who had accompanied us in our walk, and endeavoured in the most painstaking manner to make things clear, we said, pointing at random to a butt whose superscription showed it was just nine days old, ‘Is the liquor in that cask fit for human drinking?’ He answered by filling a glass, which he proffered us, but seeing a slight movement of hesitation on our part, he reassured us by drinking it off himself. It seemed to do him good, and we allowed ourselves to be beguiled into following his example. We are bound to say that our hesitation was uncalled for. The beer was good, not only fit for human drinking, but actually of such a nature as to make one desire a repetition of the dose. It was not the highest quality beer we had fixed upon – it was the ‘£4’ article; and yet we, whose judgment in the matter of malt liquors induced the editor of The Australasian Sketcher to select us for the office of ale-conner, are fain to confess that it was very good.”

This method of “cleansing” beer was not only deeply old-fashioned by 1875, it was also highly labour-intensive. A description of brewing using cleansing casks from about 1880 by an anonymous British brewer said that:

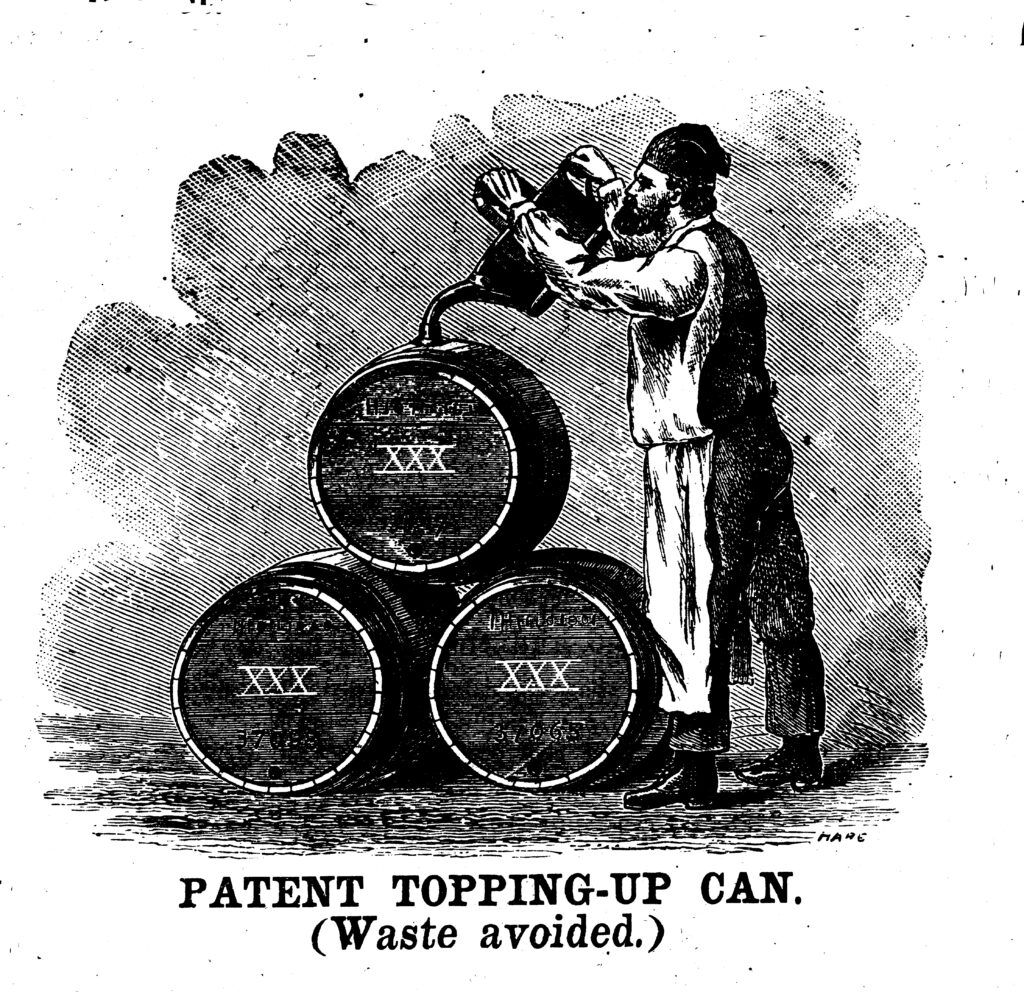

“The fermenting Beer or Stout when in the Cleansing Casks, should be filled up for the first 20 hours, about every two hour, and every 3 hours for about 20 hours more; and then about 3 times during the day, and once during the third night.”

This mean that a brewery worker had to go round with a large “watering can” filled with wort – you can see two on the cellar floor in the illustration – topping up the dozens of butts filled with fermenting beer, which were fobbing yeast out of their bungholes and down their sides into the tubs below.

The Burton union, and other systems such as the Yorkshire square and the ponto set-up were designed to automate the refilling of the casks as the rising yeast carried beer up and out of the fermenters, and also to try to make the process more hygienic: and yet Aitken, who had come from Scotland to Victoria in 1842 aged 19, and opened the Victoria Parade brewery, which became one of the largest in Melbourne, in the early 1850s, was happy to carry on “cleansing” his ale and porter the old-fashioned way.

And what about those cats? According to the Sketcher,

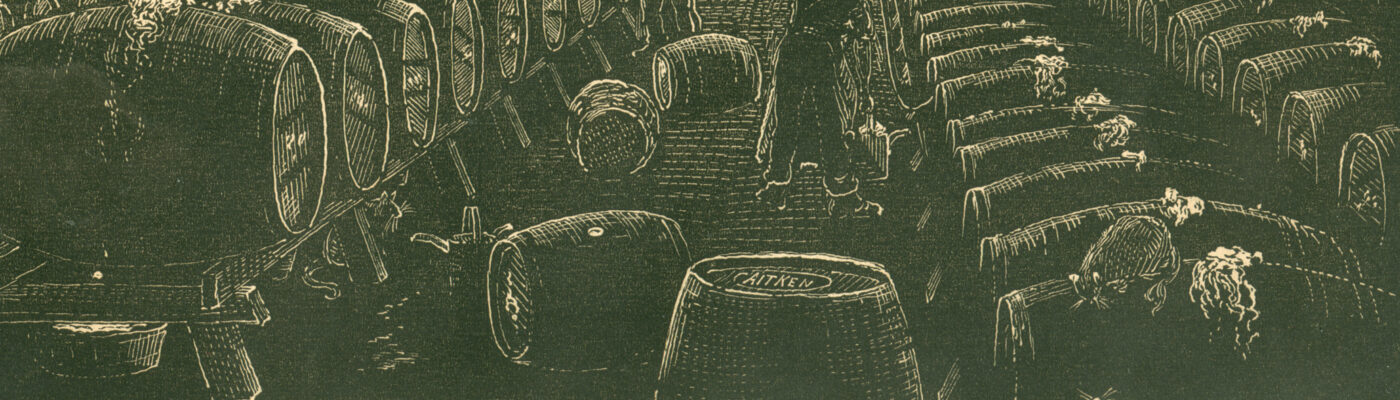

“Cats were so numerous in every quarter of the establishment that they will ever remain indelibly impressed on our mind as connected with the art of brewing. A malt-house would be a paradise for rats but for the destroying angels, in the shape of cats, that the maltster keeps to guard his portals. The rat that would attempt to eat the sack that held the malt would speedily be killed by the cats in the brewery that Mr. Aitken has built. He actually doesn’t know how many cats he has. He said at one time, mildly, about 1,000; afterwards, that he was personally acquainted with at least 50, but that there were wild ones in the recesses of his cellars at whose presence he trembled. There must be queer games played on the roofs of a brewery on moonlight nights. We know what the educated and domestic animal is capable of in the musical line. Strong men have been driven to the verge of distraction by the performances of creatures that dose [sic] away their noonday existence on the hearthrug or the sofa but what hundreds – there were certainly hundreds – of half-starved and uncivilised cats must be able to do in the way of a concert, can only he properly known to a brewer.”

Thomas Aitken died in 1884 and the business passed to his son Archibald. He retired in 1887, and the brewery passed through several hands until it was acquired by a rival Melbourne concern, the Carlton Brewery Ltd, in 1905. The Victoria Brewery survived the creation of Carlton and United Breweries in 1907 and carried on operating until 1983, making, among other beers, its namesake Victoria Bitter, which is still one of the biggest sellers in Australia. In the 1990s the main brewery building was converted to residential use. Whether there are still hundreds of cats around, I don’t know …

How many cats are in the cellar? I spotted at least eight …

This vermin prevention method continues to this very day. The Empirical Brwy. on Chicago’s north side (in its Malt Row district) harbors a number of feral cats in its brewery.

As for the puzzle, I also believed there were eight cats in the illustration.