I remember exactly when and where I first ate a chocolate creme egg: in 1957, in the kitchen of my parents’ council house in Stevenage. My Uncle Bert, who had no children of his own, had clearly decided to treat his little nephew with an Easter novelty. My experience of chocolate Easter eggs to that point had been limited to the hollow variety: that a version filled with sticky sweet white and yellow gick existed was beyond my limited five-year-old ken. Thus, after I removed the foil from the egg, and, at the urging of Uncle Bert, whose motives I feel were not totally altruistic, I bit into the egg and discovered with surprise and trepidation that it was not, after all, hollow, as I had innocently suspected. The look on my face, I am sure, was the reward for his generosity that Bert was expecting: bit of a joker, Bert.

Those of you who have been paying attention to happenings in the world of confectionery will be puzzled at this point: surely Cadbury, king of the creme egg, has been celebrating 50 years of creme eggs this year: so how was I being startled by my first experience of one 64 years ago? The answer is, of course, that the history of confectionery is no less convoluted, complicated and paradox-filled than the history of anything else, be that beer, the British Empire, or baseball.

I’m sure proper confectionery historians will be swift to correct me, but the earliest reference to chocolate creme eggs I have found is from 1912, in the Denbighshire Free Press, North Wales, where J. Powell-Jones, wholesale and retail confectioner, of High Street, Denbigh, was offering for sale a range of Easter treats far wider than you might find today: not just plain chocolate eggs, but wooden eggs, tin eggs, cardboard eggs, “snake eggs” (no, no idea), marzipan eggs – and chocolate creme eggs, plain or tinfoiled, three old pennies a pop (about £1.30 in modern money).

How close Mr Powell-Jones’s creme eggs were to the modern Cadbury incarnation (or in-ovation – mildly amusing Latin pun alert) I have no clue. There were chocolate creme eggs on sale in the United States in the 1920s, and also a product called “Cream [sic] Eggs chuck full [sic again – that would be “chock full” in British English] of fruits and nuts, chocolate covered and packed in bunny boxes [sic a third time]”, and “Purest Jelly Bird Eggs”, which, assuming this is not a reference to something called the Jelly Bird, I am struggling to comprehend. My understanding is that “jelly” across the Atlantic covers that segment of the category known all-encompassingly in Britain and Ireland as “jam” that is made solely from fruit juice, rather than pureed fruit. Jam bird eggs? All suggestions welcome.

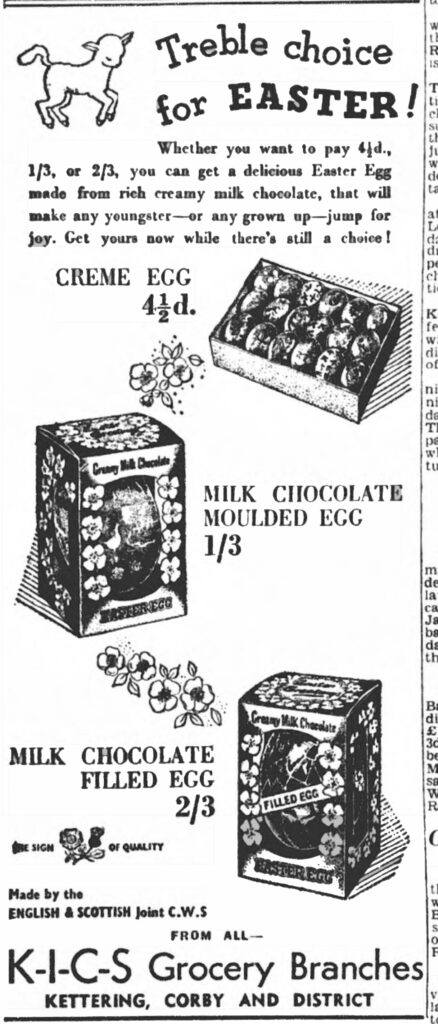

In Britain the chocolate creme egg looks to vanish, before reappearing in 1957, when they were being made by the Co-operative Wholesale Society, the manufacturing arm of the Co-op retail movement, which was a considerable force on the High Street in pre-supermarket days. Adverts show Co-op stores selling CWS creme eggs, clearly wrapped in printed foil, for 4½ (old) pence – a 50 per cent (nominal) price rise in 45 years, though in real terms those eggs cost the modern equivalent of 46p. I strongly suspect it was a Co-op egg Uncle Bert gave little nephew me for the lols of seeing my surprised face when I bit into it those many decades ago.

Internet sources suggest Fry’s, the former Bristol chocolate firm taken over by Cadbury’s, began making creme eggs in 1963, with the brand name changing to Cadbury’s Creme Egg in 1971 – hence the “Golden Goo-bilee” celebrations this year. I’ll put my slightly sticky, chocolate-stained hand up and admit to having an occasional Creme Egg since Uncle Bert introduced me to them: as Noël Coward would have said, if he had been addicted to Dairy Milk, “Strange how potent cheap chocolate can be.” I was, therefore, intrigued by the announcement that the Goose Island brewpub in Shoreditch, East London, offshoot of the Chicago-based, AB-Inbev owned brewery famous for its Bourbon County barrel-aged stout, was making a Creme Egg Stout in honour of the 50th anniversary of Cadbury’s Creme Eggs, In honour of Uncle Bert, I thought, I have to try that.

Alas, this turned into a massive PR disaster for Goose Island, as the beer went on sale on its website on a Monday morning a few weeks before Easter and sold out withing less than two minutes. Would-be Creme Egg Stout drinkers found that even though they had successfully completed the first part of their purchase, in the seconds it took to click through to “checkout” their order could not be fulfilled, because all the beer had been sold. Disgruntlement was spread wide, and I fear I might have had a little bit of a rant on Twitter at how foolish it was of Goose Island to massively underestimate the love the British have for Creme Eggs, and not realise that a Creme-Egg-themed beer was likely to be hugely popular, their failure leading to considerable bad feeling – certainly from me, anyway.

Hurrah, though, for Jonny Tyson of Beerwrangler.com, top, top man, highly recommended for all your advanced cicerone needs, IBD-certified beer sommelier, beer educator extraordinaire, who saw my distress and stepped up where Goose Island had fallen on its face to supply me with a precious can of the otherwise impossible-to-find Creme Egg Stout. What a warm, wonderful human being.

And, er, was it worth it? I was expecting something like a Creme Egg when it’s been sat on – a sticky mess. But it was actually rather good, clearly brewed by someone who knew what they were doing, and with all the nods to its ovoid inspiration one would hope for: the chocolate and vanilla came though well, the aroma was good, and there was just enough roasty bitter to balance the milk sugar sweetness. At 4.5 per cent abv it was rather thin – 5.5 per cent alcohol would have been better. But overall, while not a classic, this was a fair stab: silver medal level. Be encouraged to do it again next year, Goose Island – but make about ten times as much.

Here in the States, we say “chock full” also. Never heard the other.

Typo?

The beer sounds better than I (as someone who steers well clear of Peanut Butter Milk Stouts, and that sort of thing, as a rule) would have expected. Perhaps Gose Island will rew a bit more next Easter?

not just plain chocolate eggs, but wooden eggs, tin eggs, cardboard eggs, “snake eggs” (no, no idea), marzipan eggs

I have a very faint memory of my family having a set of painted (and lined) wooden eggs, which my parents would ‘give’ us every Easter – presumably filled with chocolate of some description, but I don’t even remember that. Seemed very special at the time, but you try it with kids these days… mutter mutter and as for advent calendars don’t get me started mutter mumble

I suspect that what was called “jelly bird eggs” would now be what we call jelly beans. And we Yanks do make a distinction between jelly and jam – jelly will typically be thickened with gelatin so it is a firm mass (Welch’s grape jelly being the stereotype), whereas jam is just pectin based and more fluid.

Mmmm, but in these islands anything made from tree fruits that you can spread on bread is a jam, even though it might be called “jelly” – we have “bramble jelly”, for example, which is made from blackberries, but it would still be recarded as falling in the “ja,” category. “Jelly” is reserved as an actual category for what Americans call jello, ie something that sets solid, cannot be spread, and is eaten as a dessert.

Separated by a common language 🙂

I am guessing jelly bird eggs are what is more commonly known as jelly beans (at least here in the US)

Cadbury creme eggs originally used the same trick as After Eights, which were introduced around the same time. The filling starts off solid, which allows it to be coated with chocolate in the same way as the original Fry’s Chocolate Cream, but the filling contains invertase which partially inverts the sucrose after a few days turning the solid into “goo”. It’s a really clever bit of food technology, originally proposed by H.S. Paine in 1924 – but relies on the availability of invertase in industrial quantities (although they now avoid the expense of the enzyme by putting liquid goo into frozen chocolate shells). From what I can tell invertase only became available in the kind of quantities needed in the late 1950s.

I suspect the early “cream” eggs were more like chocolate truffles, using actual cream to provide the texture.