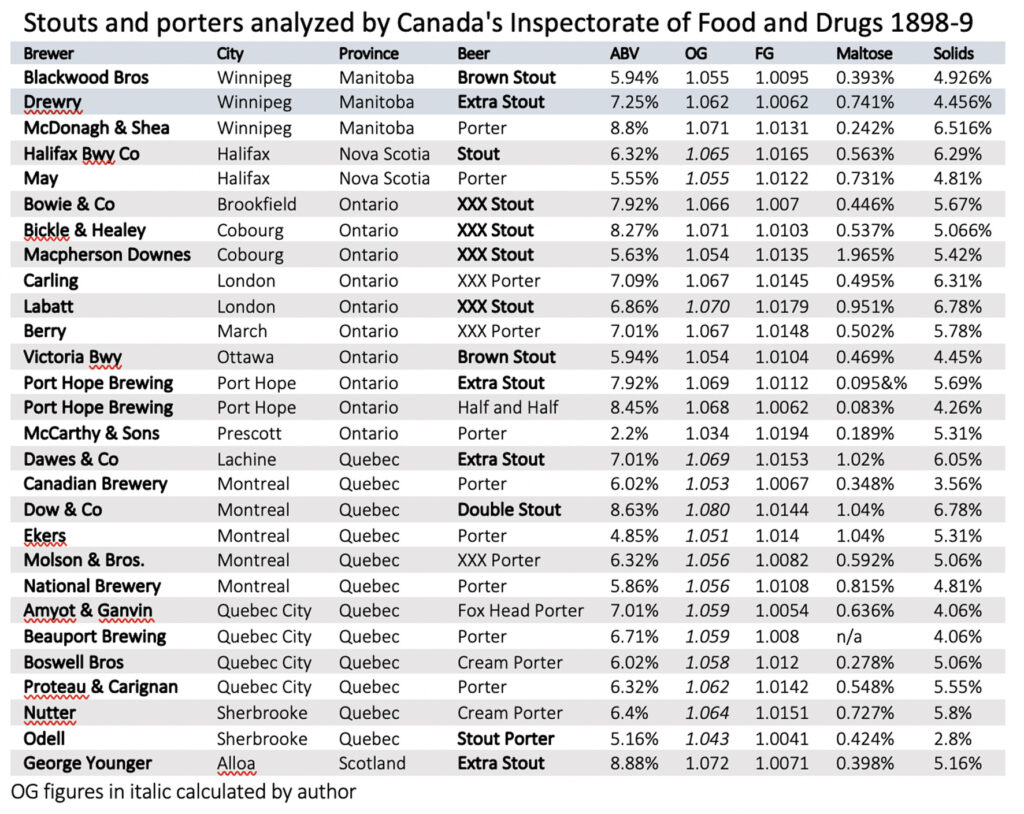

In 1898-9, Canada’s Inspectorate of Foods and Drugs analyzed beers from 33 Canadian breweries in four provinces, of which 27 brewed a porter or a stout, and one stout brewer sold a half-and-half. They also analyzed the extra stout from George Younger’s brewery in Alloa, Scotland, to give historians a useful comparison with stout brewing in Britain.

The figures show up the differences between porter and stout in the 1890s, as brewed in Canada, at least. The average strength of the 11 Canadian stouts analyzed was 7.06 per cent alcohol by volume. This was rather less than George Younger’s Extra Stout, at 8.88 per cent abv, but more than all bar two of the 15 porters. Taking out the strongest of the porters, brewed to 8.8 per cent abv by McDonagh & Shea of Winnipeg, Manitoba, the average strength of the Canadian porters was 5.73 per cent abv, nearly 20 per cent less than the average stout strength. The two beers had almost identical average apparent attenuation, at 81.4 per cent for the porters, and 81.5 per cent for the stouts. Other analyses show big differences, however. The average percentage of maltose in the finished beer was 0.594 per cent for the porters, and 0.747 per cent for the stouts. The average percentage of solids in the finished beers was 4.99 per cent for porters and 5.6 per cent for the stouts[i].

We can conclude, therefore, that Canadian porters at the end of the 19th century were, on average, weaker, as one would expect, than Canadian stouts, and, given residual maltose as a likely proxy for apparent sweetness and percentage solids as a likely proxy for mouthfeel, the stouts were 25 per cent sweeter than the porters, and they had a 12 per cent greater mouthfeel, giving, together with the higher alcohol, a fuller, more powerful beer.

Younger’s Extra Stout, by comparison, looks to be probably drier-tasting than most of the other stouts, with a mouthfeel slightly below the Canadian stout average. Those average figures, however, hide some wild outliers: the XXX Stout from Macpherson Downes in Cobourg, Ontario had more than 20 times the residual maltose that was found in the Extra Stout from Port Hope Brewing a few miles east along the shoreline of Lake Ontario. (Macpherson Downes looks to have become Macpherson Gordon soon after, and did not, it appears, have long to celebrate any “sweetest stout in Canada” title: the brewery burned down in early 1899, with a loss of C$20,000.)

[i] Report, Returns and Statistics of the Inland Revenues of the Dominion of Canada for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30 1899 Part III Adulteration of Food Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 1899, pp28-33

There’s a lot of relatively low final gravities there for a porter or stout. I rarely get any any dark beer finishing much lower than 1012 – with big stouts around 1020. Yet quite a few of these are under 1008. Would this be the result of Brettanomyces ? Maybe it’s time to test with a mixed fermentation.

I would imagine that yes, Brett is indeed the answer …

Martyn –

an interesting article, as always.

However, as I know you would agree, this is a snapshot of a certain place at a certain time.

I think it is pretty much established that, overall, through different times and places, there is not a hard and fast set of criteria which define and seperate the two types.

A few years ago we had these endless, sterile debates centering around the BJCP rules about “porter is this, stout is that…” – please let’s not revive that argument…. No-one has the energy. Do they?

I’m not reviving any argument, mate: just making what I hoped was an interesting observation about how stout and porter differed in one place at one time.

Martyn –

My comments were not aimed at you, as I hoped I had made clear, and hopefully the BJCP “not true to style” etc nonsense is behind us now.

As a snapshot, the article is very interesting.