Millions of words, and dozens of books, have been written about Guinness, the beer, the brewery, and the family, and a perhaps surprising amount of inaccurate mythology (and sometimes pure nonsense) has crept into the story. Here is a short list of some of the “facts” that writers, some of them supposedly authoritative sources, most frequently get wrong about Guinness, which you’ll find repeated all over the interwebs, whenever someone lazily repeats something someone else never bothered checking:

“Arthur Guinness was born in 1725.”

Almost certainly not. His memorial in Oughterard graveyard, Kildare, states that he was “aged 78 years” when he died on January 23 1803. This means that he must have been born some time between the last week in January 1724 and the first three weeks, two days of 1725, making it around 15 to 1 on that he was, in fact, born in 1724.

“Arthur’s father, Richard Guinness, brewed beer for Arthur Price, the Archbishop of Cashel … One of Richard Guinness’s duties was to supervise the brewing of beer for the workers on the Archbishop’s estate.”

There is no evidence at all – AT ALL – that Richard Guinness, or Arthur Guinness, ever brewed for Price, at any time. There was no brewing for “the estate workers” because the home that Price built in the village, Celbridge House (now Oakley Park) did not actually have an estate attached, only a few acres. In any case, if any household brewing took place, it would have been done by lower-grade servants, not someone who was being referred to in the 1740s as “Richard Guinness, gent”.

Richard Guinness worked for Arthur Price from at least 1722, when Price was Dean of Kildare (having been Vicar of Celbridge since 1704), and already on his way up the ecclesiastical career ladder to an eventual archbishop’s mitre. However, Richard’s role was as household agent, receiver, factotum and steward to Price, based in Celbridge.

The “Richard Guinness brewed for Archbishop Price” myth is sometimes supported with invented “facts” – here’s the Oxford Companion to Beer making stuff up:

“In 1722 Arthur Price purchased the small, local Kildrought Brewery and placed Richard Guinness in charge of production.”

An ounce of fact has been spun into a pound of fiction by people not thinking hard enough. Come on: what would a high-flying Protestant cleric be doing getting involved in anything as low-life as a commercial brewery? The facts: In 1722 Arthur Price bought a house, stables, garden and maltings in Celbridge that had previously been occupied by a brewer, James Carbery. The house was bought, apparently, as a home for Price’s employee Richard Guinness and Richard’s family. Carbery, meanwhile, stayed on in the brewery and inn next door, which is still in operation as a drinking place today. (“Kildrought”, incidentally, is the older form of Celbridge, from the Irtish Cill Droichid, “Church by the bridge.”

Edward Bourke in The Guinness Story claims on no known evidence that it was Richard Guinness who “leased James Carbery’s Brewery in Celbridge in 1722. (The location is now the Mucky Duck pub).” Three errors here the “Mucky Duck” site is the house that stood in front of James Carbery’s maltings, not the brewery, and it was this house that was Arthur Guinness’s first home: there is no evidence of brewing there, and it wasn’t leased by Richard Guinness, but bought by Arthur Price. (Celbridge pubs seem to have an unfortunate habit of changing their names: the Mucky Duck currently [March 2019] appears to be called simply the Duck, while James Carbery’s former brewery and pub became Breen’s Hotel, then King’s, then Norris’s, and is currently the Village Inn: on the wall of the Village Inn is a plaque that misspells Carbery’s surname.)

Sometimes the story develops into total fantasy. Here’s the idiocy that Stephen Mansfield, author of The Search for God and Guinness: A Biography of the Beer that Changed the World, came up with:

“The archbishop’s estate was known for the dark beer that was brewed there, the pride of Dr Price and the envy of his guests. Many a guest tried to question the reverend’s trusted agent to find out how he produced such a fine-tasting drink. Naturally, Richard, proud of his celebrated dark stout, would never say. Some said that Richard Guinness once accidentally roasted his barley too long and that the caramelized result was stronger and better than any other brew.”

Laughable. Barley roasted too long will never “caramelize,” of course, which requires the presence of sugar, and roasting certainly won’t make beer stronger: the opposite, indeed, since the roasting destroys starch that could become sugar that could become alcohol..

There’s worse, amazingly. Sometimes the story becomes garbled into total nonsense, like this, which is copied verbatim from, of all places, the Northern Ireland Tourist Guide hub:

“The original Guinness recipe is said to have been created by a Welshman known as Arthur Price. Arthur brought the recipe to Ireland and hired Richard Guinness as a servant. The recipe would be passed on to Guinness who would, of course, create the drink we all know and love.”

Another bizarre and distorted version of Richard Guinness’s early career appeared in a book called Here and There Memories by the sporting writer John Joseph Dunne, published in 1898. Dunne, whose other books include How and Where to Fish in Ireland: A Hand-guide for Anglers, was presumably spun the yarn while dipping his rod in the Liffey, which flows past Celbridge. According to Dunne, “the first Guinness was an ostler at the Bear and Ragged Staff, a little inn at Celbridge,” whose talent as a brewer (no, I don’t know what an ostler, whose place was in the stables, was doing in the brewhouse either) was spotted by a brewer called Sweetman from Dublin, who “brought him into his employ.” Multiple problems here: no evidence of an inn at Celbridge called the Bear and Ragged Staff (though there WAS a Bear Inn in the village in the mid-1800s); no evidence that Richard Guinness was ever an ostler, which would not, in any case, fit with his later career as man of business for the Reverend Dr Price, something that implies much more education than an ostler is likely to have had; no evidence tbat Guinness ever worked for the Sweetmans; and the Sweetmans were a dynasty of Catholic brewers, thus unlikely, anyway, to be hiring the Protestant Guinness.

However, Dunne’s story appealed enough to be repeated in at least one Irish paper, the marvellously mastheaded Nenagh News and Tipperary Vindicator (where do Irish traffic cops live? Nenagh, nenagh, nenagh …) and has subsequently polluted history, so that you can now find claims that Richard was actually the proprietor of a Celbridge inn called the Bear and Ragged Staff. In fact, the year Dr Price died, 1752, Richard married a widow called Elizabeth Clare, who had been leasing the White Hart inn in Celbridge since 1749, an inn that had been mentioned by an English traveller in 1732 in terms that suggested it was the main inn in the village. For inexplicable reasons a number of websites give Richard’s second wife’s surname as Clere: the marriage records clearly show it to be Clare, and when her son Benjamin married Richard’s daughter Elizabeth, the surname again was given as Clare. (When the White Hart disappeared does not seem to be known: it has been claimed that it was being run by a man called Thomas Coleman in the 1890s, but Coleman’s inn remains unnamed in all the mentions I have been able to find.)

Richard Guinness – and Arthur – most likely learned to brew after Richard’s marriage to Elizabeth Clare, and the Guinnesses’ new involvement with the White Hart, which happened when Arthur was 28. Three years after that, in 1755, Arthur acquired a proper brewery, in Leixlip, just two and a half miles away for an Irish crow, though rather further by Irish roads. Another persistent myth involves the £100 each that Richard Guinness and his son Arthur were left in Archbishop Price’s will when the prelate died in 1752. The Oxford Companion to Beer fantasising again, claims, that “Price … specified that [the £100] should be used to expand the brewery.” Of course, there is actually nothing in Price’s will to support this nonsense.

Plenty more people assert, again without evidence, and without thinking if the claim makes sense, that:

“Arthur Guinness inherited £100 from his godfather Archbishop Price in 1752, and used the money to set up a brewery in Leixlip.”

Ignoring the three-year gap between Arthur being left money by the archbishop and the acquisition of the Leixlip brewery, £100 in the mid-18th century is the equivalent today of only £14,000 today, not enough to start a business on. It is clear that, rather than Arthur relying on the archbishop’s bequest to start his career, Richard Guinness was able to save enough in the three decades he worked for Price, and then the three years he spent running the White Hart with his new wife, to help fund his eldest son’s move into commercial brewing, which would have needed much more than £100.

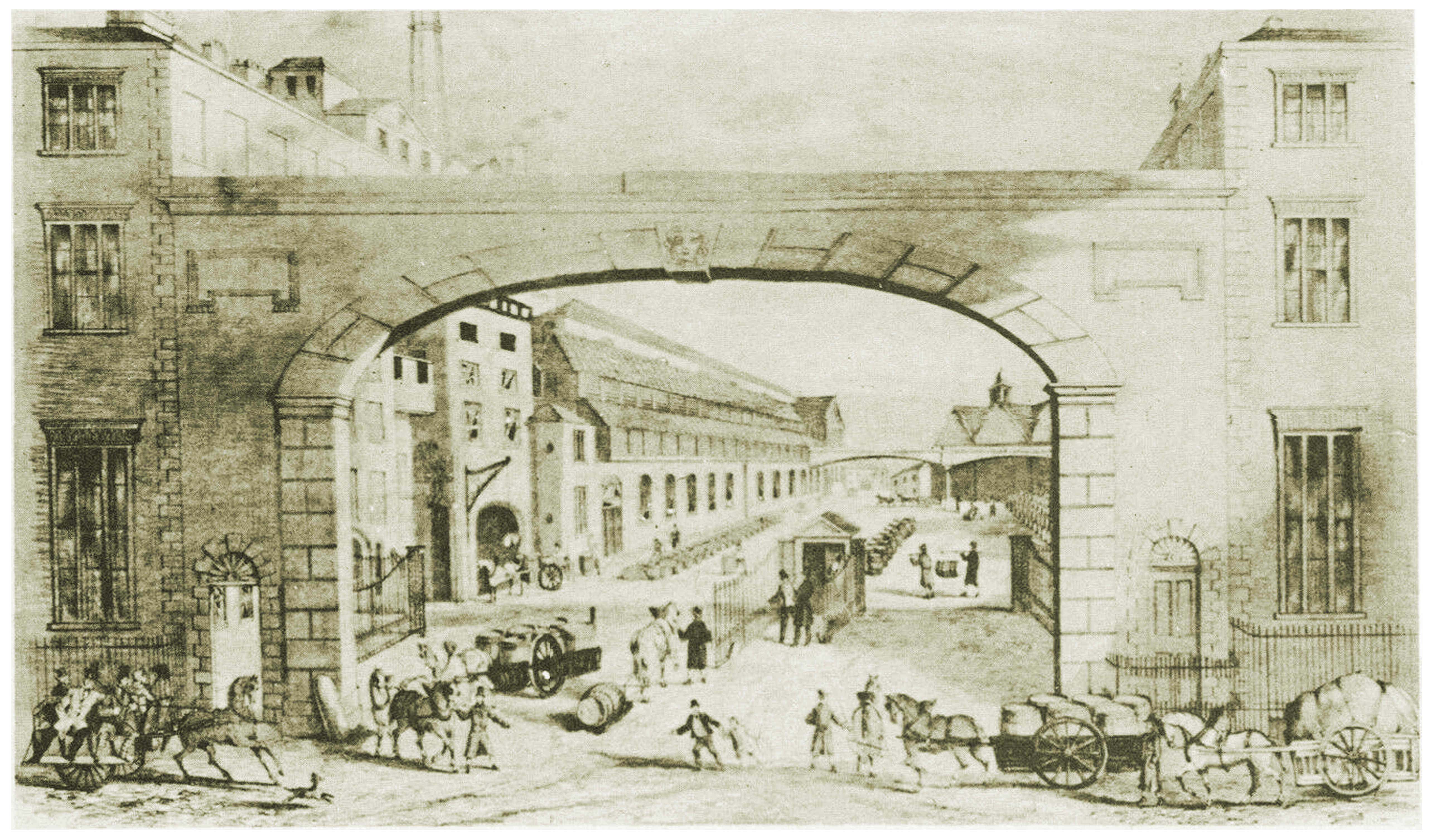

Occasionally the mythologists ignore the Leixlip brewery and try to claim Arthur used his £100 inheritance to purchase the lease at St James’s Gate. The date that Arthur acquired his first brewery is often incorrectly claimed as 1756. To be fair, a major study of Arthur’s earliest years, Lynch and Vaisey’s Guinness’s Brewery in the Irish Economy 1759-1876, gets this wrong, mixing up the brewery acquisition with a later land purchase in Leixlip by Arthur. The Leixlip brewery was taken on in 1755: Arthur was named as “of Leixlip, Co Kildare, brewer” in September that year, and in 1773 he was described as a brewer of 18 years’ standing. The date of 1756 applies to more property in Leixlip that Arthur began leasing that year from an American, “George Bryan of Philadelphia in the province of Pennsylvania.”

Occasionally the mythologists ignore the Leixlip brewery and try to claim Arthur used his £100 inheritance to purchase the lease at St James’s Gate. The date that Arthur acquired his first brewery is often incorrectly claimed as 1756. To be fair, a major study of Arthur’s earliest years, Lynch and Vaisey’s Guinness’s Brewery in the Irish Economy 1759-1876, gets this wrong, mixing up the brewery acquisition with a later land purchase in Leixlip by Arthur. The Leixlip brewery was taken on in 1755: Arthur was named as “of Leixlip, Co Kildare, brewer” in September that year, and in 1773 he was described as a brewer of 18 years’ standing. The date of 1756 applies to more property in Leixlip that Arthur began leasing that year from an American, “George Bryan of Philadelphia in the province of Pennsylvania.”

Can cap this. On a tour of the Halve Maan brewery, in Bruges, the guide solemnly assured us that the Guinness brewery had once been destroyed in a fire. When salvaging what remained, a quantity of burnt, black malt was found. Making the best of a bad job, this was brewed up, and lo! Guinness was born. Seemingly, I was the only guest not nodding sagely in agreement…

Foolish man … everybody knows it was accidentally burnt barley, not malt …

[…] Everything You Don’t Want To Know About Guinness: ten Guinness myths that need stamping out now.Not your average listicle. […]

If I would like to dig in to Guinness history, not necessary 18th century could be more recent also, do you have a book to recommend?

Joe Joyce’s The Guinnesses is probably the best all-rounder

I’m sorry, but I got my slightly different story from Hon. Desmond Guinness many years ago when he was the official historian of the Guinness Brewery (he’s now in his 90s, but highly regarded in Ireland as an historian). He said that Arthur Price was born in Dublin, but his father was originally from Wales, where stout and porter were indigenous drinks (Price is a Welsh name). As Archbishop Price was on his deathbed in 1752, he called in his servants (most of them members of the Guinness family) to give them a farewell present, and the unusual Price family recipe he had for brewing was one of the things that he left them. I don’t think you can get any closer than that to the horse’s mouth!

Thank you for your comment, John, but with the greatest respect to Desmond Guinness, that story simply does not match up to the known, verifiable facts about both the history of porter and Arthur Guinness’s involvement in brewing it.

“Wales, where stout and porter were indigenous drinks” – not true. Stout and porter come from London, originally. Porter was being imported from London to Dublin from the late 1730s at least.

There is no evidence that brewing was taking place at Price’s home in Celbridge.

There is no evidence at all that Arthur Guinness was brewing porter before the late 1770s – 25 years after Price’s death.

There is overwhelming evidence that Dublin brewers were fighting imports of porter from London, that they hired porter brewers from London to help them learn how to brew the drink, and it took a long time before they were able to match English porter brewers in quality.

There is no evidence at all for an “indigenous” Welsh stout and porter brewing tradition.

Price IS a Welsh name though – so that bit is true.

Porter was indeed a drink from Wales before it was from London. Young Welsh men looking for work went to London, where they got jobs as “porters” carrying goods on and off ships (there being few cranes in those days), and they quickly got London brewers to produce their home drink. The fact that Guinness did not immediately brew porter or stout has no bearing on whether Price gave out the recipe on his deathbed!

That, I am afraid, is what historians call “total and utter embarrasingly laughable nonsensical shite”.

Someone posted that my comment about Porter originating in Wales was “shite.” I’m sorry, but that sort of remark is in the nature of “ad hominem,” which is way below the level of discussion presupposed by this site. If he has solid evidence with which to dispute my comment, he should produce it.

‘that sort of remark is in the nature of “ad hominem,”’

Actually, it isn’t. An ad hominem argument is that claim that your argument is invalid because of who you are, not because of the facts and logic you present. The idea of an ad hominem is sometimes loosely extended to the practice of characterizing you based on your arguments. An example in the present instance would be to conclude that you are shite. But this is not in fact what was written. What was actually written is a characterization of your argument. There is no hominem involved.

I’m sorry, but you’re the one making the claim that the origins of porter are in Wales, and it’s up to you to provide the evidence to back that claim up – which you can’t do because it’s total nonsense. ALL the contemporary 18th century statements about the development of porter say it happened in London. There is no dispute about this at all.

I assert, as I have been told numerous times by people who should know, that illiterate young Welshmen came to London looking for work in the first 20 years of the eighteenth century. The only work that many of them could find was as porters for loading and unloading ships. These Welshmen missed their local ale-like drink and asked London brewers to make it for them. The earliest written mention of porter was thus in London in 1721. If these Welshmen were illiterate, why would it have been mentioned in Wales earlier? That does not preclude it from having been first a Welsh drink. Much of history, I’m afraid, has no surviving documentation, and this appears to be one of those cases.

“I have been told numerous times by people who should know” – I don’t care how many times you’ve been told, and who told you, that’s not evidence. What you need is actual written evidence from the early 18th century confirming this. There isn’t any.

“lliterate young Welshmen came to London looking for work in the first 20 years of the eighteenth century. The only work that many of them could find was as porters for loading and unloading ships. These Welshmen missed their local ale-like drink and asked London brewers to make it for them.” Nonsense on several levels. Ignoring, again, the utter lack of evidence for hordes of Welshmen being employed as porters in London, and anything like porter being brewed in Wales early in the 18th century, and the utter lack of any evidence of London brewers resonding to appeals by Welshmen to brew the beer they drank back home, it would have been impossible for outsiders to find employment loading and unloading ships: the portering trade was strictly regulated by the City of London, and only members of the Fellowship of Porters were allowed to do the work. Outsiders would not have got a look-in.

“Much of history, I’m afraid, has no surviving documentation” – but the history of porter has plenty of surviving documentation, and none of it, at all, mentions Welshmen or the roots of porter being in Wales. Instead the surviving documentation makes it perfectly clear that porter developed out of the London Brown Beer that had been brewed for a couple of centuries, and that it was done by London brewers with no outside promptings.

It looks as if we will simply have to agree to disagree. Just because people are illiterate and can’t write down their own history is no excuse for shutting them out of it.

I’m not “agreeing to disagree” at all, I’m telling you that you are talking total nonsense, and if you continue to repeat this ludicrous and evidence-free idiocy then you will be widely regarded as a fool.

Dear Martyn

I was looking at your site. Very enjoyable. I saw the ad for the Lantern 10-sided Tankard from Stephensons. I tried to order a couple but was told they do not deliver in the United States. Can you recommend anyone in the USA who might sell them? I tried Amazon but no luck.

Alas no, but you shoulkd be able to find them being sold occasionally on eBay …

[…] https://zythophile.co.uk/2019/03/30/everything-you-dont-want-to-know-about-guinness-ten-guinness-myth… […]

[…] https://zythophile.co.uk/2019/03/30/everything-you-dont-want-to-know-about-guinness-ten-guinness-myth… […]