It’s a curious fact that the expression “pale ale” does not seem to appear in the English language until 1705, in a catalogue of newly published books sold at a shop in Little Britain, a street just off Smithfield. What makes this particularly surprising is that pale-coloured ales had been available for a very long time: many thousands of years, in fact. Indeed, it has to be pretty certain that the first beers we know of, brewed 13,000 years ago in the Middle East, were pale ales.

Excavations between 2004 and 2011 of a burial site at Raquefet (or Raqefet) Cave in Israel, used by the people we call Natufians 13,000 years ago, showed evidence of crushing grains of malted wheat or barley and brewing beer in stone pits dug into the floor of the cave, quite likely as part of funereal feasts.

The Natufians, who were named for the Wadi en-Natuf near the Palestinian town of Shuqba, in the Judaean Mountains, where the first evidence of their culture was uncovered by archaeologists in the 1920s, were a semi-nomadic people whose diet included gazelles, and the grains of wild barley, Hordeum spontaneum, the ancestor of modern brewing barley. This grows throughout the Fertile Crescent, the area in south-west Asia that saw the birth of Western agriculture. Even today, in some parts, wild barley “often occurs in very dense stands in large populations”.

The exploitation of wild barley as a food goes back before modern humanity: studies carried out on the teeth of Neanderthal skeletons from 60,000-plus years ago found in the Shanidar cave, on the edge of the Fertile Crescent, in modern Iraq, suggest they were eating cooked barley grains. Grains were being harvested by the Sea of Galilee, not far from Raquefet cave, by modern humans 23,000 years ago: we know this because of the remains found on the microliths used to make reaping scythes from that period.

Barley grains are hard and not that pleasant to eat, but if you soak them in water, and let them begin to sprout, they become both softer and sweeter, as the enzymes in the barley seed start to turn the starches into the barley into sugar. If you then dry the sprouting barley seeds before they use all their sugar up to grow into new barley plants, you have a product – malt – you can keep, and transform into different foodstuffs – including beer.

How humanity worked out that malt could be turned into beer is something we still don’t know, but you can be pretty sure it wasn’t some kind of accident, because if you start leaving wet grain around, the most likely result is mouldy grain, not anything drinkable. My personal favourite theory at the moment is that the evidence shows Neolithic peoples were exploiting honey, which makes it quite likely they knew diluted honey could undergo a transformation – fermentation – into happy juice. (If you think this is unlikely, the San people in Southern Africa hunt out babobab trees after rainstorms, since they know honey beers make their nests in the hollows of the trees, and after the nests are flooded and the honey diluted, it will turn into natural mead.) Our ancestors were just as intelligent as we are, and they must have noted the similarity between sweet diluted honey and the sweet wort obtained from malted grain. If one ferments, they very probably thought, why not the other, and set about adding fermented honey to sweet wort …

(A huge hat-tip here to Graham Dineley for his suggestion that the Hebrew expression “ארץ זבת חלב ודבש”, which occurs more than 20 times in the Bible, and is usually translated as “land of milk and honey”, is better translated as “land of milk and sweet wort”.)

Anyway, let us not distract ourselves. How did the Natufians dry their malted grain? It’s the Middle East – you don’t need a fire, Just leave it out in the sun. And what colour malt do you get if you dry your malt in the sun? And what colour will the beer be that you make from sun-dried malt? Let’s quote the great Norwegian recorder of traditional brewing practices, Odd Nordland, from 1969:

“The malt was dried on stones in the sun. It was spread out on rugs, or on furs … The sun-dried malt produced a very pale ale.”

So: the Natufians, 13,000 years ago, were brewing (if they were brewing: not everybody agrees that’s what the evidence shows) with pale sun-dried malt a pale ale. So were the Sumerians, ten thousand years later. As Merryn Dinely wrote in 2016:

“The earliest written description of how to make malt and brew beer is the Hymn to Ninkasi, inscribed on a Sumerian clay tablet and dated to around 1800BC … A floor maltster today would recognise the techniques undertaken by those Sumerian maltsters thousands of years ago … Grain was steeped in water, then it was spread out on a floor and finally the malt was dried in the sun.” (My emphasis)

A slightly more sophisticated method of drying malt looks to have developed by around 7,000 years ago. At Jarmo, a Neolithic village in the Zagros mountains, in modern-day Iraq, occupied around 5000BC, structures described as “baked in place basins”, ovoid depressions with burnished clay rims, have been found by archaeologists. The suggestion is that a fire was lit on the surface, then cleared away once the clay was hot enough to dry the malt.

It may have looked like this grain-drying area at Ses Tanquettes farm, Majorca, Spain. Note the gutter around the edge which, when filled with water, would have kept insects away from the drying grain.

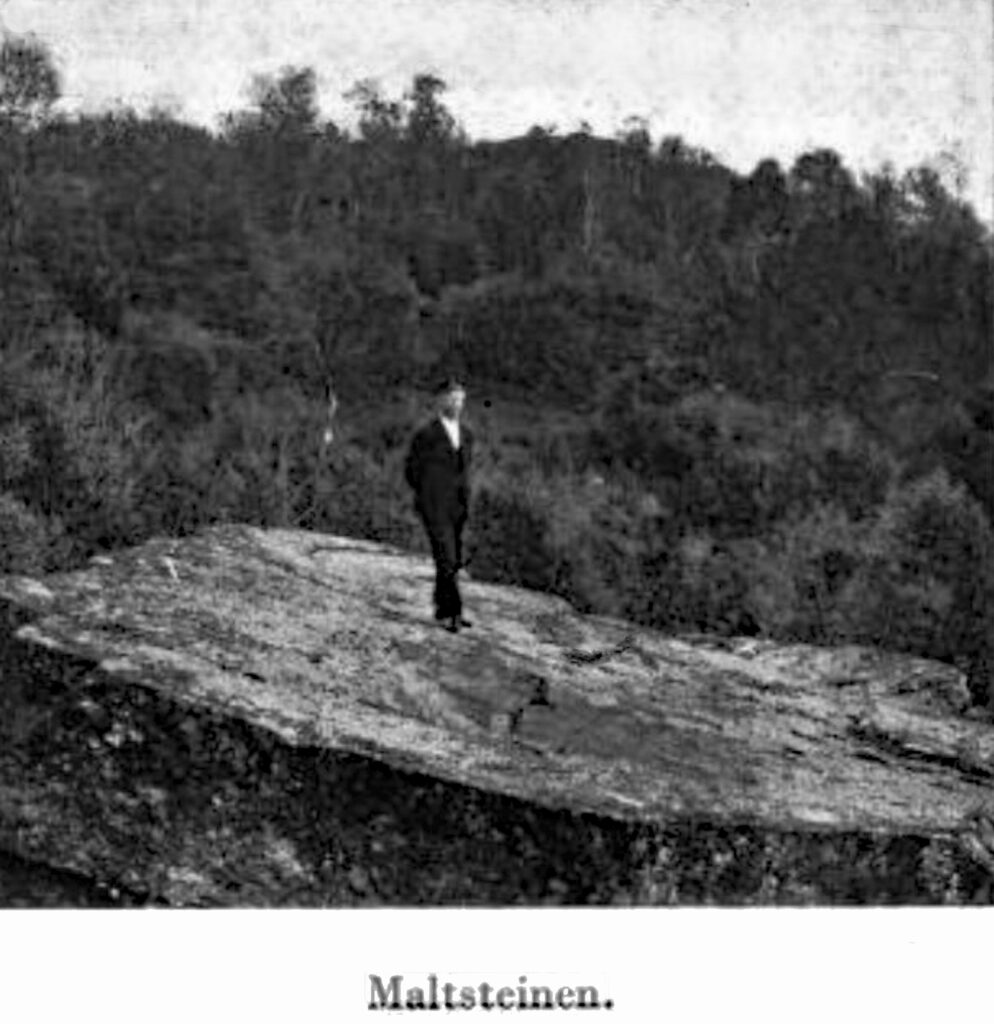

From around 8,500 years ago, agriculture, including the growing of grains such as barley, began to spread from south-west Asia into colder, wetter, less sunny areas of Europe, reaching Scandinavia and Britain about 6,000 years ago. But did this mean the end of sun-dried malt? It did not. At Rauland, in Telemark County, southern Norway, is Maltsteinen, “the malt stone”, used by farmers in the past to dry their malt on in the sun. It lies further north than anywhere in mainland Britain. If you can sun-dry malt in southern Norway, you can sun-dry malt anywhere in the British Isles. And when you use sun-dried malt, you’re making pale ale. (Hat-tip due to Lars Marius Garshol here for telling me about Maltsteinen.)

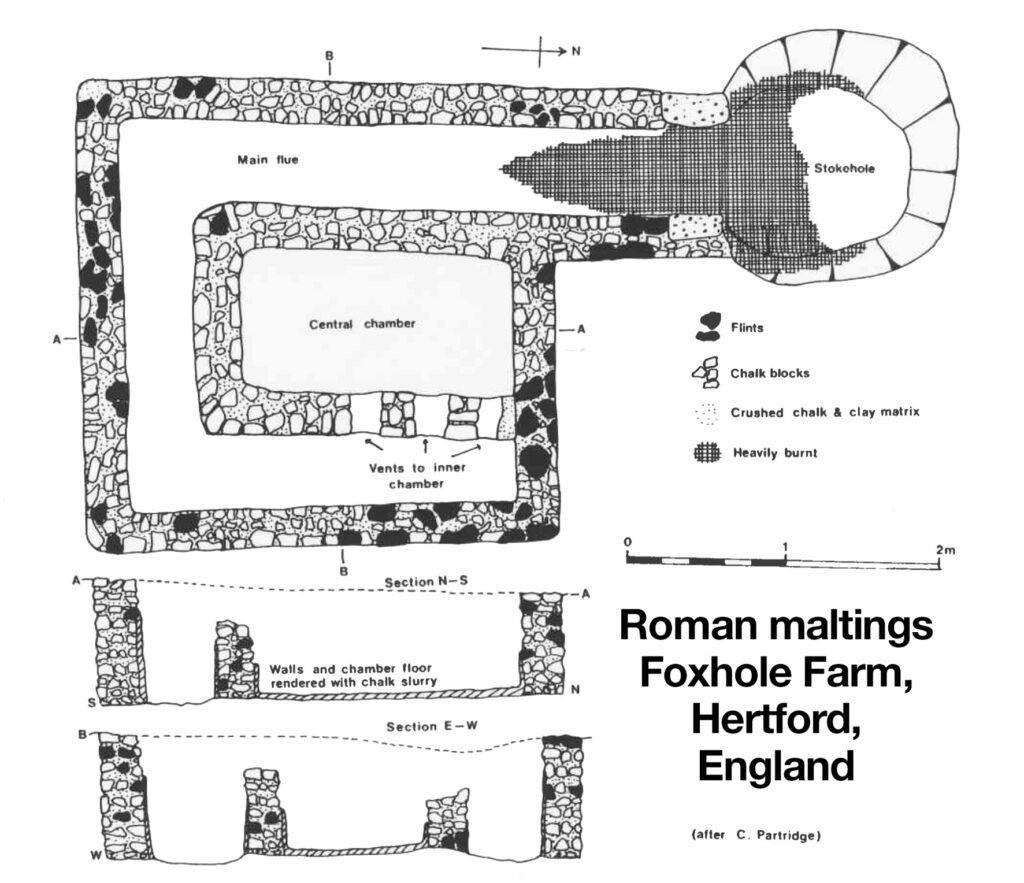

Of course, much of the time the weather in Britain and Ireland won’t be sunny enough to dry malt in the open successfully, and by the Iron Age, at the latest, artificial methods of drying malt had been developed, using fires that delivered remote heat to malted grain to dry it. Here’s a plan of a Roman-era malting kiln founds on the edge of Hertford, a few miles from the town of Ware, which from the 18th to mid-20th centuries was THE big malting centre in England. The Foxhole Farm maltings was reconstructed, and found to be capable of producing a perfectly acceptable amber-coloured malt.

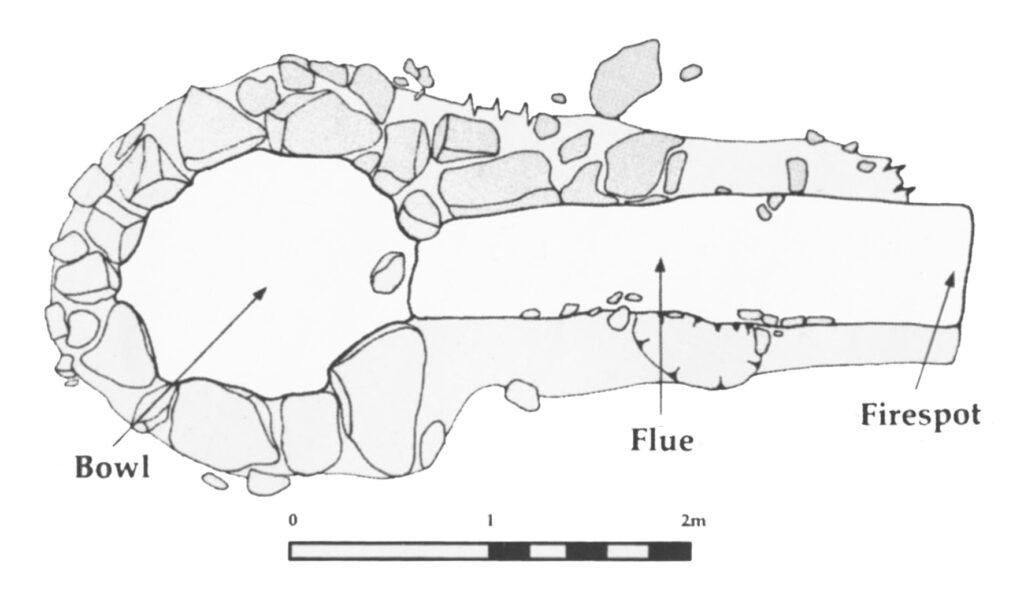

After the Romans left, a slightly different method of drying malt was developed. There are hundreds of examples of remains of grain dryers/malt kilns in Britain and Ireland from the post-Roman to the Early Modern periods constructed on a “keyhole” plan.

All the same, sun-drying malt persisted. Thomas Tryon wrote in The New Art of Brewing Ale and Other Malt Liquors in 1691:

“The best and most natural way of drying Mault is in the Sun in April or May, especially for those that makes but small Quantities for their own use, this makes, not only the palest, but the most Kindly and Wholesome of all others; the Drink made thereof has a delicate fine mildness, being of a warming exilerating quality, not so apt to heat the Body, nor send Fumes into the Head. In all hot Seasons it may be done, every Man may dry enough for his own use.”

It was said of the 1st Duke of Beaufort, Henry Somerset (1629-1700), who lived at Badminton House in Gloucestershire with a household of 200 servants, that “all the drink that came to the duke’s table was of malt sun-dried upon the leads of his house”, “leads” here meaning “window sills”. (Thank you, Marc Meltonville, for explaining to me what leads were!) As you can see from this illustration of the duke’s unassuming little home, he had a very large number of windows, and this, presumably, a very large number of nicely wide sills on which to spread malt to dry, protected by the glass from birds and vermin.

Commercial malt, and thus commercially brewed ale – and beer – remained generally brown until the first use of coke to dry malt, in Derbyshire around 1642. William Ellis wrote in The London and Country Brewer, in 1736, that “the Coak is reckoned by most to exceed all others for making Drink of the finest Flavour and pale Colour, because it sends no Smoak forth to hurt the Malt with any offensive Tang, that Wood, Fern, and Straw are apt to do.” But just as important was the introduction of indirect heating. At the same time as the introduction of coke to dry malt came a host of patents for kilns to dry malt with indirect heat, starting with Sir Nicholas Halse in 1635, with an invention ”for the dryinge of mault and hops wth seacole, turffe, or any other fewell, wthout touching of smoake”

Continental brewers, in particular German brewers, noted these “English malt kins”, using indirect heat: an “englische Malzdarre”, English malt kiln, which dries the malt using hot air generated by hot smoke passing through pipes to heat the malt without the smoke ever coming into contact with the malt, was mentioned and illustrated in a book published in Dresden in 1785. These were the sort of “English maltings” installed at the Citizens’ brewery in Pilsen in 1842 to produce pale malt.

However, continental brewers continued with air-drying to make pale malt, as described by Georges La Cambre in Traité complet de la fabrication des bières et de la distillation, published in Brussels in 1856:

“Sometimes the germinated grains are dried on kilns or hot-air dryers, sometimes in attics, that is to say in the open air or in other words, in the wind, as is the practice in some localities, in Belgium, in Holland, and in Germany, for certain beers.

“In order to effect the desiccation of malt in the open air, they were still content at Louvain to spread it in very thin layers on the floor of vast, well-ventilated attics, and to stir it by means of wooden rakes.“All the malt used in Louvain is germinated for a very long time, air-dried and always brewed without first separating the rootlets which exist in large enough quantities to give the white beer its taste of a bitterness and a particular odour.”

In summary, then:

● It has been possible for at least 13,000 years to brew pale ales and beers with sun-dried or air-dried malt

● English brewers, able to make pale malts with coke-fuelled maltings, abandoned air-drying

● Continental brewers, for diverse reasons, kept on with air-dried malts, so that there was a witbier/Weissbier band using air-dried pale malt across Northern Europe from Belgium to Poland

At least one reason for this is that air-dryed malt is highly diastasic, meaning brewers could use large amounts of unmalted wheat to make their wit/Weisse beers.

(This is, in effect, the talk I gave to the second Ales Through the Ages conference at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia in November. My grateful thanks to Frank Clark, Whitney Thornberry and all at Colonial Williamsburg for organising a tremendous weekend of fascinating talks from great speakers on the history of beer and brewing, probably the best beer conference I have ever been to.)

The “pale ales” being referred to in the early eighteenth century were, given the distinction then between ale and beer, presumably pale versions of mild or old ales rather than the bitter beers which appeared about a hundred and twenty years later. Does anyone know how the meaning shifted from the former to the latter?

The sense of “ale” as lightly hopped, versus beer as well-hopped, seems to have disappeared in the 1820s, and the difference then became ale equals pale, beer equals dark (ie stout). This was reinforced when pale bitter ales became a widespread “thing” from the early 1840s onwards. Because pale ale copuld now be mild of bitter, that’s when drinkers started asking for “bitter, please”.

Surely ‘leads’ are the leaded roofs of the hall?

You would think: but Marc Meltonville, who knows much more about this stuff than I do, says “leads” means window sills, and if leads DON’T mean window sills, at least occasionally, then this quote from William Ellis’s London & Country Brewer, 7th ed, 1759, p254, doesn’t make sense: “He also was a nice Person, that had his Malt dried on Leads, through Glass Windows, by the Sun only; as it was performed by one in Sussex.”

Most interesting and informative.

Many thanks,

Trevor Heywood

Mr. Cornell, Do you know if the speakers at the second Ales Through the Ages conference at Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia were recorded? If they were do you know if there is a posting of the speakers text anywhere on the internet? I have been following your blog for a few years now and always am delighted when I find an email sharing your most recent post. Thank you for sharing what you learn about beer and brewing in general, in your travels and studies.

Wishing you a Merry Christmas and Happy New Beer, I mean Year.

Peace

Joe Wood

I beliueve they were recorded, but you need to ask the organisers, not me.

I think Mr Dineley’s speculation is quite unlikely. Date honey is a well known middle eastern delicacy, still consumed in the levant today, and dates are a prominent food both in the biblical and archeological records. It’s possible דבש typically refers to date honey (although sometimes it clearly refers to bee honey, for example, the Samson narrative), and beer is significantly less prominent. While it was clearly consumed in the land of Israel during the neolithic period, that doesn’t mean it was a popular foodstuff in the Iron Age.

There are a number of problems with your criticisms (1) “It’s possible דבש typically refers to date honey ” – many things are possible, but just because something is possible, it doesn’t make something else “quite unlikely”. (2) beer was drunk by people to the south (Egypt), the north (the Hittites) and the east (the Sumerians) and yet you want us to reject the idea that it could be popular in Palestine/Israel? (3) The lack of prominence of “beer” in the Bible is at least as likely to be an artifact of translators’ idiosyncracies: שֵׁכָר seems generally to have been translaterd into English as “strong drink”, but quite probably much of the time meant “beer”. We don’t actually know what שֵׁכָר meant for certain, but since šikaru was the Akkadian for beer, then “beer” seems as likely a meaning for שֵׁכָר as not

There are a great many problems with your response. To wit: A. It is very apparent you have copy-pasted the Hebrew words from wikipedia which somewhat undermines the validity of your argument. B. It is incredibly anachronistic to refer to Iron Age Israel and Judah as ‘Palestine/Israel’. No serious scholar would do so. You may have been looking for the word Canaan. C. I do not read the Bible in translation, but as I was referring to the material culture and archeological record, this is only marginally relevant. The plain fact, accessible in any excavation report of Iron Age Israelite and Judahite sites, is that there is wide-scale evidence for industrial-scale olive oil and wine production, wide-scale evidence for consumption of wine and grape products, and a paucity of evidence for beer consumption. D. The climates and cultures of Egypt, Sumeria, the Hittite lands, and the Levant are not remotely similar. If you presented significant evidence of beer consumption and production in Ammon or Aram-Damascus, you would have an argument. I agree that שכר is almost certainly etymologically connected to the Akkadian but refer to a Biblical lexicon: how many instances are there of שכר as compared to יין (Yayin/wine)? Compare to the Egyptian literature: how many references are there to beer there?

“It is very apparent you have copy-pasted the Hebrew words from wikipedia which somewhat undermines the validity of your argument.”

Why?

“It is incredibly anachronistic to refer to Iron Age Israel and Judah as ‘Palestine/Israel’. ”

So what?

“No serious scholar would do so.”

Who cares? Please don’t think you can embarrass me by telling me I don’t use the terminology “serious scholars” use – that’s just petty amnd pretentious snobbery, and frankly not worthy of someone attempting to pose as a “serious scholar” themselves. You knew what I meant.

The absence of evidence for industrial-scale beer brewing in Israel/Judah compared to industrial-scale wine making and olive oil production isn’t the least surprising, and certainly does not prove beer brewing was not taking place: wine and olive oil are tradeable products thanks to their long shelf-lives. Pre-hop beer – ale, properly, but achaeologists insist on using the anachronistic term “beer”, so we’ll stick with that – would have lasted not much longer than, eg, bread before spoiling, would not have been traded, would not, therefore, have been produced on an industrial scale, and would have been produced, in Judah/Israel, only domestically, and on a domestic scale. Domestic-scale brewing required pots and other implements that would be pretty much indistinguishable from any other sort of domestic pot, in the archaeological record. Industrial-scale brewing was taking place in Egypt and Sumer, because they had large and permanent establishments, such as temples, which required large supplies of beer to supply the people there. (Indeed, the invention of writing, of course, sprang directly from the need to track and record supplies to such places.) No such establishments existed in Judah/Israel, no my knowledge – I have no doubt at all you will tell me if I am wrong.

Further, if beer WAS solely a domestic drink, and not a status drink, as wine appears to have been, one would not expect multiple references in biblical source. So again the absence of multplle references to beer in the Bible is not evidence of beer’s absence from life in Israel/Judah.

Whatever the Jewish tribes were doing, in any case, according to a publication by Michel Dayagi-Mendels put out by The Israel Museum in Jerusalem (Drink and Be Merry: Wine and Beer in Ancient Times, 1999, p124) “In the late 2nd Millennium BCE, the custom of beer-drinking seems to have been widespread among the Philistines,” referencing Judges 14:10-12, and among the illustrations (p122) are a Philistine beer jug from the 12th century BCE and three pottery beer jugs from the 9th to 8th century BCE found in Northern Israel. These jugs have a pierced strainer and a spout at the side, and a handle at right-angles to the spout, suggesting the contents were drunk straight from the jug, and contained grains or grain fragments, that needed straining out. According to Drink and Be Merry, “jugs such as these began to appear in the early 1st millennium BCE in Israelite settlements as well.” So there is certainly evidence of beer consumption in a Palestinian/Israelite context.

Excellent research and a very interesting article. It resets the presumptions on beer once more, txs!

Thank you Martin, for the best Christmas present, hat-tipping the “land of milk and honey”.

In another blog I suggest how these Paleolithic people could have stumbled upon proper malting, including the raking and turning to inhibit growth, that is the critical bit that most people miss. Findings of carbonised, processed food, in the Shanidar cave indicate that there was sophisticated processing 70,000 years ago:

https://merryn.dineley.com/2020/08/origins-of-grain-agriculture-some.html

In this blog I attempt to dispel the confusion between beerstone and calcium oxalate:

https://merryn.dineley.com/2021/11/beerstone-is-not-calcium-oxalate-and.html

Merry Christmas, everybody.

I’m always very happy to steal your ideas, Graham – and Merryn’s too!

Bavarian brewers/maltsters saw making air-dried malt as the proper step for making darker kilned malts. Germination was pretty much always stopped by air-drying the green malt on a separate floor, the *Schwelkboden*, before this air-dried malt was put on a kiln to dry it even further. From what I could gather, this only stopped when double floor kilns popular, as the pre-drying step could now be done on the top floor of the (usually) hot air kiln, which took hours instead of days.

That’s extremely interesting, Andreas – do you know what Bavarian wheat beer/Weisse brewers did?

Sorry for replying so late. At least in the 19th century, they either just air-dried their malt (both wheat and barley malt) for their Weißbier, or in some cases, kilned the air-dried malt at very low temperatures (IIRC, 30 to 40°C), but always ensuring that the malt remained as pale as possible.

No apologies needed – that’s what I would have guessed, so it’s great to have it confirmed.

A truly excellent summary of the genre.

Thank you Clive, you’re very kind

Its not necessary to dry malt to make beer? It can be pounded into a slurry when its malted and then used to mash with a bit of stirring. I wonder if drying came in when the process was industrialised and as the grain is a lot easier to crush when dried but pounding does introduce a lot of small particles of husk which can be difficult to filter.

Drying, I sujspect, came in simply when people wanted to make beer later, rather than right away after germinating the grain. The “bits” are why you see Sumerians (and others) drinking through straws …

Drying, I suspect, came in simply when people wanted to make beer later, rather than right away after germinating the grain. The “bits” are why you see Sumerians (and others) drinking through straws …

Great article. Bamberg is still celebrating the date of the first patent for indirect kilning as the dying date of smoked beer. https://www.wiesentbote.de/2021/07/21/23-juli-wird-tag-der-rauchbierbewahrung/

That’s very funny, Christoph – the date they are marking is when Sir Nicholas Halse registered his patent for an indirect-heat malting method in London. I wouldn’t think anyone started using indirect heating on Germany for another 50 years at least. (Their maths is also wrong: they’re claiminbgf it was 486 years previously, it was, of course, only 386 years …)

Yes, I always found that ironic. Guess they tried to find as old a date as possible. And yes, the newspaper guys were not good with their maths 😀

[…] missed this by Martyn in last week’s round up, a neatly parallel piece to mine in 2014 on how beers in the past […]

Hocam Ellerinize Saglık Güzel Makale Olmuş Detaylı

Martyn, thank you for this great article. It was an amazing read as I am now wandering into this air-dried malt stuff which is truly an eye opening moment for me.

There is a couple of questions which I wish you can help me fill the void as follows.

1) Do you have any idea of how popular (or how common) the use of air-dried malt or ale that was brewed with this particular type of malt before the introduction of pale malt from indirect fire kilning technique in Britain?

2) Do you find any disadvantages of air-dried malt in comparison with malt that is produced by using Wood, Fern, and Straw as a heat source in kilning process?

Here are my opinions:

– First, the air-dried malt will required a lot more of time and labor, hence higher price.

– Second, I would also assume that it can be produced in a small quantity per batch because of the aforementioned reason.

– Moreover, I suspect that the moisture content in air-dried malt will be higher than those that are subjected to higher temperature heat source (fire/smoke). Therefore, it creates an environment which better favors the growth of microbes which lead to poor malt shelf life.

– And lastly, it is deems to be difficult for maltster to deliver consistence malts batch after batch.

Please let me know on your thought.

Thank you and Cheers!

Hi, Napat, thanks for your comments. In answer to your questions:

1) No idea: I don’t know of anycomments as to the popular9ity of air-dried malt in Britain

2) Air-dried malt is going to be much more dependent for its making on the weather: you need a hot, sunny day. But apart from that, it has a number of advantages over kiln-dried malt: no cost of fuel; no smoky tang; much more diastasic;m lovel golden colour of the wort.

I’m not sure the air-dried malt would have needed more time and labour: kilns need watching, and the grain still needs turning. Plus, as I said before, you are saving on the cost of fuel for the kiln.

I would certainly guess that the moisture content would be higher in air-dried malt, but I don’t know enough to say what that would mean in terma of shelf life etc.

I don ‘t believe the maltster was that bothered about a consistent product: that’s an Industgrial Age concept.

Cheers, Martyn

Martyn, thank you for the feedback. I am very fascinated by this air-dried malt topic. Now it makes me wonder because this can be considered as one of the oldest techniques to dry green malt in which a super pale color (+high diastatic power) malt is achieved.

However, it seems like the perception of medieval-time beers or 16-17th century beers in Europe are sort of dark-color muddy one (I’m thinking about Braunbier in Bavaria, Bock bier from Einbeck or Porter in Britain). This come with an exception of Wissebier in Bavaria as I understand that from historical record they included the used of this air-dried malt in the brew hence the pale color beer is yielded. My point is shouldn’t there be more of pale color beers mentioned in the history prior those that we now know today as pale ale, pilsner and etc. This is what I wonder…

Cheers!

Napat

This is exactly what I needed to read today. Thank you.