So, what was it like, the ancient lager Carlsberg spent two years and hundreds of thousands of kroner recreating, resurrecting yeast out of a bottle dating back to 1883, pulling out 130-year-old brewing records, growing an ancient barley variety, hiring a floor maltings, working out the most likely hop varieties to use, reproducing the original brewing water, having oak casks made in a Lithuanian cooperage, making moulds of vintage bottles so that new versions could be hand-blown, and then flying in dozens of journalists and beer writers to Copenhagen from as far away as Malaysia and California to drink the result.

It was … OK.

And that, of course, was entirely the point. The Re-brew project, which culminated in a tasting in Copenhagen last week, was a celebration of the unexceptional, a tribute to the work of the Carlsberg scientist Emil Christian Hansen, whose invention 133 years ago of pure yeast cultivation enabled brewers for the first time to produce guaranteed standardised beers, so that the buying public could be sure the pint they were about to open would be as good as yesterday’s, and the one the day before, and the one tomorrow, without exception. That the world’s beer drinkers appreciated this can be easily demonstrated by the wealth amassed by the Jacobsens, owners of Carlsberg, and the way Carlsberg became literally a name known in every household, not only in Denmark but around the world.

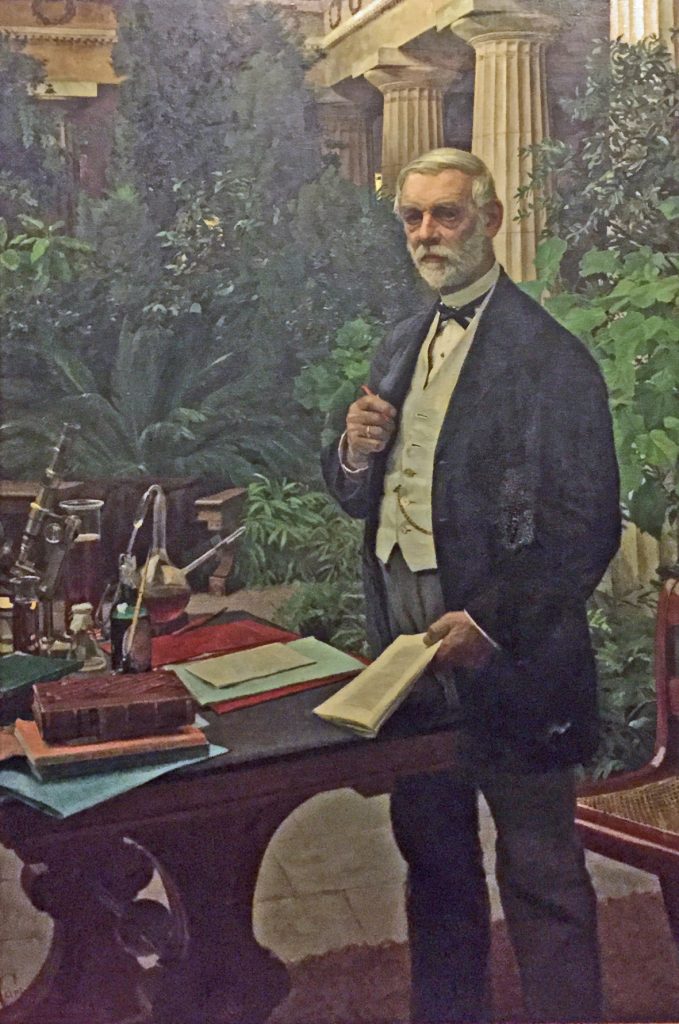

Standing in the huge pillared conservatory at JC Jacobsen’s former home in Valby, Copenhagen, sipping the re-brewed 1883-style beer, a clear, clean, bright, copper-coloured Vienna-style lager, slightly sweet, a tiny bit lacking in condition, made with a barley variety called Gammel Dansk, literally “Old Danish”, and lightly hopped with Hallertau Mittelfrüh (the records showed only that the hops game from the Hallertau region, so the variety was a guess) while Carlsberg’s chairman, Flemming Besenbacher, and CEO, Cees ’t Hart, made speeches and photographers bumped elbows trying to get shots of Eric Lund, head brewer at Carlsberg’s laboratories, filling glasses from a wooden cask (hence the lack of condition), it would be fair to wonder what the fuss was about. This was certainly not a beer to knock anyone’s socks off.

But sock-knocking potential was not what this beer was ever about. The aim of Hansen – and his boss – was to give Carlsberg drinkers value-for-money consistency, and that’s what they got. In isolating the pure strain of yeast that was then used to make the beer in the bottle from 1883, and every other bottle of Carlsberg lager since (more or less: today’s Carlsberg yeast has apparently changed only slightly, genetically), Hansen invented modern industrial brewing. If the phrase “industrial brewing” makes your lip curl like a wine drinker on first encountering a Belgian brown sour, I’m afraid you don’t really understand beer. Dismissing mass-market beers is like dismissing the Ford Focus and saying F1 racers are the only valid form of motor car. Some terrible crimes have been committed under the banner of industrial beer, that’s true. But overall, industrial beer has brought more happiness to the mass of humanity than craft beer ever will, and EC Hansen is a vastly more important person in the history of beer than Ken Grossman. (Not least because Hansen’s boss, JC Jacobsen, refused to keep the Carlsberg lab’s findings for the company’s sole profit, and made the science – and the pure Carlsberg yeast strain – available to any brewer who wanted it.)

Even so, and accepting that bottle of 1883 lager’s importance in the history of beer, was it worth reproducing the beer inside it? It’s fun for geeks like me, as I told the Danish newspaper Politiken, to taste “hvad vores oldeforældre drak. Her kan jeg i så høj grad som muligt dele en oplevelse, de havde. Det er en forbindelse tilbage i tiden.” (except in English, of course.) It was fun for all those involved at Carlsberg, too: Birgitte Skadhauge, vice-president for research at Carlsberg, who was in overall charge of the project, told me that everybody at the company was very excited about it, and I’m sure that’s accurate. The level of detail in reproducing the old beer was fanatic: the brewing liquor, for example, was first purified and then mineral salts added to match the water from a 68-feet-deep well dug out in January 1883, that is, exactly contemporary with the yeast.

The excellent internal PR available from this sort of venture should never be underestimated. If, as a Carlsberger, you get fed up with sniping from the beer snobs who only rate (in all senses) brews from “craft” concerns, it’s great to get involved in something with history and heft, something no small brewery would have the resources to pull off, in time or money or technological expertise, something that underlines the history the company has, and its importance in the history of beer brewing as a whole. Carlsberg’s influence goes beyond its perfection of techniques to isolate and propagate pure yeast strains that even the tiniest craft brewer today benefits from. For example, plenty of craft brewers make their wackiest beers with Brettanomyces yeast, but Brettanomyces was first properly discovered, studied and named by someone working in the Carlsberg labs in Copenhagen.

I’m sure when the research guys went to the Carlsberg Foundation, which controls the company, and said: “We’ve found this old beer bottle from 1883, the year EC Hansen perfected pure yeast cultures, that still seems to have viable yeast cells in – wouldn’t it be a great idea to recreate an 1883-style lager with it, and can we have the cash to do so?”, the foundation immediately spotted the trumpet-blowing possibilities, both inside and outside Carlsberg’s walls, and happily opened the corporate wallet. The 140th anniversary of the foundation itself, in 2016, was approaching, and here was something that could be tied in with the anniversary, and used to make Carlsberg people feel good about Carlsberg, as well as, hopefully, make other people feel good about Carlsberg. They could make a film about it (warning – contains scenes of me in a pub), they could fly in loads of journos who would surely say nice thinks about how clever Carlsberg was, and they could round it off with an excellent meal for 140 people prepared by a man who used to work at Noma in Copenhagen, probably the best restaurant in the world, with the Crown Prince of Denmark turning up to sprinkle his royal blessing over us. (Strangely, the last and only other time I was in a room with the Crown Prince of Denmark was when he was promoting another Danish brewer entirely, Mikkeller, during a Danish Trade Week in Hong Kong.)

And so we have it. Loads of effort for, um, something that wierdo beer geeks like me, and plenty of people at Carlsberg, certainly enjoyed, but you can watch the Canadian beer writer Stephen Beaumont and the Californian beer writer Jay Brooks struggle to be complimentary about the result here. I wonder what, say, the 15 or so journos flown in from Israel, or the guy from the paper in Malaysia, both places where Carlsberg is an increasingly big player (and wants to be bigger), thought when they tasted this new/old beer. “Is that all there is?”, I fear.

Still, I’d like to thank Carlsberg very much for enabling me to have another great night in the Taphouse with what must be the finest line-up of beer writers ever gathered around a Copenhagen bar table, including not just Stephen Beaumont and Jay Brooks but Jeff “Beer Bible” Alworth and Stan Hieronymus, also from the US, Pete Brown from the UK, Evan Rail from Czechia and Ron Pattinson from the Netherlands. And I certainly found more challenging beers to drink in Copenhagen than Carlsberg’s Re-brew project. The next day I tried a lunch-time trip to Mikkeller’s new-ish Øl & Brød cafe, just up the street from the original Copenhagen Mikkeller bar in Viktoriagade, where I had an excellent karrysild smørrebrod –slightly spiced herring open sandwich on rye bread with a lightly poached egg – accompanied by a small glass of Hvedegoop, a fine wheat-based barley wine from Mikkeller and Three Floyds, followed by what was basically rhubarb crumble à la danoise, with a small glass of Mikkeller passionfruit Berliner Weisse, which went absolutely brilliantly together, the tartness of the rhubarb and the sourness of the beer complementing each other superbly, a marvellous example of a beer-and-food pairing where the sum was considerably greater than the two pretty-good-on-their-own parts. The one downer was that lunch for one, albeit a very tasty lunch for one, cost me 306 kroner – £32 for one small sandwich, a bowl of crumble and two small beers.

To put that in context, my ticket to the Copenhagen Beer Festival later that afternoon, including 20 beer tokens, only cost me 325kr, and as a Camra member I was given more beer tokens for free: indeed, I had so many tokens in the end, I gave quite a few away to Stephen Beaumont, who was returning to the festival the next day. The Copenhagen fest is “American-style”, meaning you only get “tasters” of 10cl (for standard beers) or 5cl (for strong beers): that’s fine for some of the stuff on offer, but nothing like enough for the more drinkable beers. There were some 80-plus stalls, serving mostly Danish beers, and staffed, frequently, by the brewers themselves (something Camra still mostly doesn’t get right), though there was at least one Polish brewer represented, some Americans (Sierra Nevada, Brooklyn, Rogue, Widmer and others) at least two or three German (Schneider, Crew Republic, a microbrewery in Munich), quite a few British brewers’ beers (Fuller’s, BrewDog, Sam Smith’s, St Austell, Wychwood to namecheck four), some Belgians, including Westmalle and, to my personal amusement, Grimbergen (apparently Carlsberg now how the distribution rights outside Belgium for Grimbergen: big brewers from the days of Watney’s more than 30 years ago have been trying to promote Grimbergen’s abbey-style brews, with no success, for the excellent reason that they’re not very good); several from Italy, notably Baladin and Del Borgo; O’Hara’s from Carlow in Ireland; at least one Faroese brewery; Einstök from Iceland; and one stall each from the Taybeh brewery in Palestine and the Alexander brewery in Israel (these two were at the furthermost ends of the hall, a converted locomotive shed, from each other, though I was told that in fact the brewers are friends, and I believe it – beer accepts no boundaries).

The crowd looked a proper cross-section of Danish society – much more so than you would see at the GBBF, with a fair number of smart older middle-aged couples, and a definite lack of large groups of men in their 30s. The beers were solidly “eurocraft” – almost 100 per cent keg or bottled (I saw only three handpumps), large numbers of imperial stouts and double IPAs – though with a Danish spin, thanks to the influence of the Ny Nordisk Øl movement and its emphasis on local ingredients, so that there were plenty of beers around with sea buckthorn, sweet gale and the like as their bitterers, rather than hops, and even one “amber ale” with real extract of (presumably Baltic) amber in it, Cold Hawaii (the name of a Danish surfing centre), from Thisted Bryghus: distinctly resiny, and not one I’ll rush back to.

Unlike Copenhagen, which I’d definitely rush back to: lovely city, friendly, welcoming people, great bars. And if Carlsberg decide their next revival will be the double brown stout they used to brew in the 19th century from a recipe JC Jacobsen’s son Carl apparently nicked off William Younger when he was apprenticed to the Edinburgh brewer, I’d even pay my own air fare …

For more of my take on the Re-brew project, go here

Wow–that video of Stephen and Jay was one of the most awkward things I’ve seen. (It pretty well replicates the discussion Stan Hieronymus, Evan Rail, Jackie Dodd, and I had when we tasted it, too.)

Indeed. There’s a great quote from Birgitte Skadhauge in that Politiken article I link to where she tastes the beer and says in English: “Could be worse.” I think Carlsberg would have been a lot better off if they had actually said: “Look, we’re recreating what was an everyday beer here, so please appreciate it on that level and understand it on that level.”

Do you really not believe there are small Brewers with the technological expertise to recreate this beer?

Technological expertise to cultivate up a 133-year-old yeast sample? Maybe. Time, money and will to recreate what is, ultimately, an ordinary drinking lager? Including getting Memel oak casks made, ditto hand-blown bottles, ditto grow up a field of barley and specially hire a floor maltings? Very few if any.

[…] Martyn Cornell med bloggen Zytophile, var där den där dagen och han skriver om det på sin blogg Zytophile – en blogg som för övrigt alla bör läsa. Välskriven och […]

[…] were quite good. Two special beers were made available: the Carlsberg Rebrew (read about this on Cornell’s and Pattison’s blogs), which I very much enjoyed, though struggled to discover the […]