If not actually unique (always a dangerous claim to make), it was certainly a very rare sight in the cellar bar at Thornbridge Hall in Derbyshire last Monday: four draught lagers on tap from four different British craft brewers, Meantime in Greenwich (its smoked bock); the Cotswold Brewing Company; Taddington, a new Derbyshire brewery, with Moravka; and Harviestoun (Schiehallion), and no draught ale at all. Thornbridge Hall, of course, has its own brewery, and it was also where the British Guild of Beer Writers held a successful seminar on wood-aged beers last year This year it was the first seminar on lager ever organised by the guild in its 20 years of existence (a shameful omission considering lager is the beer of choice for 70 per cent or more of British beer drinkers now) and prompted by the fact that, thanks to people like Alastair Hook at Meantime and Richard Keene of Cotswold, Britons generally are starting to realise there is more to lager than being fizzy, yellow and cold.

British beer writers, naturally, would like to claim that we knew that already. But even so there has been the unspoken feeling, I suspect, that lager was something they did “over there” (points across English Channel, North Sea and Atlantic) and we didn’t have to concern ourselves with it except when we went “over there” ourselves, where we could be free to pontificate about lagering periods and decoction mashing.

There was also, as Roger Protz, who was the first speaker at Monday’s seminar, made a point of saying, a misunderstanding among British beer writers for a long time that lager was a “new” beer, invented in the 19th century, “a modern style made possible by the new technologies of the industrial revolution.” In fact, as Roger illustrated, cold storing of beer was being practised in places such as Bamberg in the 14th century, and may well go back to the 11th century at Weihenstephan, near Munich. The documentary evidence for the depth of history behind cold-brewed lager beer, of course, has just been given firm scientific support by genetic studies of lager yeast that show it developed several hundred years ago, almost certainly in Bavaria.

Paul Buttrick, a former brewer with Whitbread, revealed that even Stella Artois used to receive a respectable 42 days’ lagering, against the seven to 11 days the beer receives today. Blame the accountants? However, if building a 300,000-barrel brewery costs £6 million for 40 lagering tanks in which the beer will be stored for two weeks, but £36 million for 240 tanks in which the beer could be stored for 12 weeks, and you can’t show a 12-week lagering period produces a beer so much better than a two-week lagering period that you could charge an appropriate premium to cover your costs, then you’ve got to give the accountants some sympathy.

At the same time, Paul said, technological advances have meant better handling for beer, giving greatly reduced oxygen levels in the final packaged product, so that a beer will remain fresh for three to four months after packaging, against the two to three weeks of 50 years ago. So “lager beer is certainly higher quality today – but does it taste better?”

Alastair Hook from Meantime then gave a typically passionate account of his personal journey into an appreciation of lager as a family of beers. He expanded on points Roger Protz was making, pointing out that in Lübeck and other Hansa towns in North Germany, low-temperature kilning was seeing pale malts being produced as far back as the 12th and 13th centuries. This means Josef Groll’s “invention” of pale lager in Pilsen in 1842 was probably not the big surprise it is often painted. Alastair also underlined the need to ally the technological advances outlined by Paul Buttrick with the enthusiasm and dedication to taste experience of the modern craft brewer.

A sampling session in the Thornbridge Hall bar included some bottles brought over from Italy by Agostino Arioli of Birrificio Italiano, which is based some 20 miles north-west of Milan. Dr Arioli was one of the four panel speakers for the seminar’s second session: the others were Stuart Cail, head brewer at Harviestoun, talking about the success of Schiehallion, the brewery’s “cask conditioned” lager and currently its second-biggest seller after Bitter and Twisted; Kelly Ryan, one of the brewers at Thornbridge, but originally from New Zealand, talked about lager brewing on the other side of the world, with particular reference to Morton Coutts, the inventor of a continuous fermentation system that, basically, saw a continuous stream of raw sweet wort flow in one end and a continuous stream of lager flow out the other. Kelly confirmed what I had suspected, that it didn’t matter what this beer tasted like, since it was being sold during the years of the “six o’clock swill”, when all bars in New Zealand closed on the chime of 18:00 hours, and drinkers were anxious simply to get as much down their necks as possible.

The fourth panel speaker was me, talking about the surprisingly early beginnings of lager brewing in Britain. The “father” of modern lager brewing, Gabriel Sedlmayr, of the Spaten brewery in Munich, made at least a couple of trips to Britain as a young man in the 1830s, and one of the brewers he visited, in 1833, was a man called John Muir in Edinburgh. According to a history of the Spaten brewery published in 1997 (translation courtesy of Ron Pattinson), Sedlmayr sent Muir (whose premises were probably the Calton Hill brewery in North Back Canongate, Edinburgh) some Munich yeast, and Muir brewed several times with it in 1835. Scottish landlords seemed to love the beer made with the Munich yeast, but Muir couldn’t keep the strain pure and stopped using it. It is one of brewing history’s more titillating “what ifs” – what if Muir HAD been able to keep brewing with Munich yeast, the way Jacobsen did at Carlsberg and Heineken did in the Netherlands?

His failure, however, meant that British brewers ignored the developments that were taking place on the Continent for another 40-plus years. There were attempts to start a native lager-brewing tradition in Britain: our first lager-only brewery may have been the Bayerische Lager Beer Brewery Ltd, formed in 1881 to acquire the Eltham Brewery in Kent. However, it had vanished by 1888 (if, indeed, it ever actually opened), no more successful than almost all the other dozen or so lager brewing operations in Britain before the First World War.

(There’s always one in every audience, and on this occasion it was Mr B Glover of Cardiff, who enquired sweetly why I hadn’t mentioned the Anglo-Bavarian Brewery in Shepton Mallet, founded in 1871, which is often said to be the first lager brewery in Britain, on the grounds of its name and the fact that it brought brewers over from Bavaria to make the beer. The trouble is that there is no evidence at all that the brewery ever produced anything called “lager” or used Bavarian-style mashing and/or fermenting and maturing techniques. Alfred Barnard visited the brewery in 1890 and made no mention of lager, which he surely would have done if the “Anglo” was brewing the beer.)

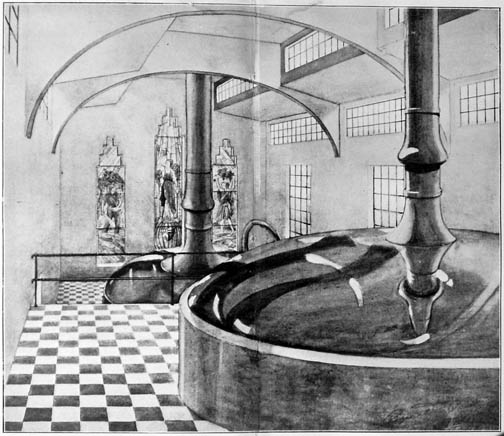

You can read much more about the history of British lager in Amber Gold and Black, my history of beer styles in Britain, including the story of how Barclay Perkins, one of London’s largest stout and porter brewers, built a complete new lager brewery in Southwark in 1921 and tried to persuade the British to drink lagers light and dark, only to be foiled because British pub landlords would NOT put the bottles on ice …

Great article, as usual. It is nice to see some of the myths about lager debunked.

On 9th January 1891, p.7 of The Irish Times had this piece under the heading “Irish Lager Beer”:

A new industry capable of much development has just been commenced in Dublin. During the present week Messrs. Stoer and Sons have started a Lager Beer Brewery at Dartry on the River Dodder, where they have been busy for the last four months rebuilding an old mill, destroyed some ten years ago by fire. The premises have been fitted up with a view to meet the present demand for Lager beer in this country, but have been so constructed that, with very slight structural alteration, the capacity can be largely increased. The building now presents a solid

and businesslike appearance and forms a strong contrast to the dilapidated condition in which it has been allowed to remain for the last ten or twelve years. A large water wheel, one of the largest, we believe, in the country, is attached to the brewery, and will be utilised to a considerable extent in working machinery. One of the special features claimed for the new beer will be its freedom from injurious clarifying ingredients which are so much used in many other beers, and as the management have had large experience in Bavarian and American breweries they confidently expect to turn out a good article. As Lager beer takes some weeks to mature it will probably be the

middle of February before the public are given an opportunity of sampling the new brew.

Perhaps inevitably, this followed on 12th August 1893 (p.8):

For Sale. The Dublin Lager Beer Brewery, situated at Dartry, Rathmines, in full working order. An enterprising party with capital would find it a very good investment. Half purchase money could

remain, or would be taken in shares. For particulars apply to John Stoer, Hanover quay, Dublin.

No-one was quite that enterprising, or stupid, it seems.

You could read from your article that continuous fermentation is a thing of the past, alas if only that were so!

One of the our 2 major brewers Dominion Breweries still uses almost exclusively Continuous Fermentation for its products, from this it brews many products including some that are marketed as ‘Craft Beers’. In particular the process has brought out a distinct amyl acetate character (banana ester) along with some other unpleasant vegital notes.

The process Morton Coutts invented was genius but then so was the atomic bomb.

Wrexham did open in 1882 by two German immigrants, Ivan Levinstein and Otto Isler, wanting to reproduce a taste of Saxony (http://www.wrexham.gov.uk/english/heritage/brewery_tour/lager_brewery.htm)

[…] that the first lager brewery in the UK was the Anglo-Bavarian brewery in Shepton Mallet. As I said here, despite its name, there is no evidence that the Anglo ever brewed lager. You can read an extremely […]

[…] This observation fits hand in glove with the key date of 1835, when Muir became the first brewer of lager in Scotland, using a Munich yeast sent to him by the pioneering lager brewer Gabriel Sedlmayer of the Spaten brewery. The experiment was short-lived, but according to Martyn Cornell: […]

[…] 🍺Lager: the truth (or some of it) | Zythophile – https://zythophile.co.uk/2008/10/13/lager-the-truth-or-some-of-it/ 🍺Lager Beer May Originate in South America and Not Germany, Research Suggests – […]