If it wasn’t for the fact that Cooper, a mixture of porter and stout, is mentioned in one of the best-known antiquarian books on drink, John Bickerdyke’s The Curiosities of Ale and Beer, published in 1889 it might be as completely forgotten today as other mixed beers, such as brown-and-mild, or light-and-bitter.

A mixture of stout and porter was promoted by Isabella Beeton, author of the best-selling Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, first published in 1861, as ideal for the nursing mother:

“The nine or twelve months a woman usually suckles must be, to some extent, to most mothers, a period of privation and penance … She will see that the babe is acutely affected by all that in any way influences her, and willingly curtail her own enjoyments, rather than see her infant rendered feverish, irritable, and uncomfortable. As the best tonic, then, and the most efficacious indirect stimulant that a mother can take at such times, there is no potation equal to porter and stout, or, what is better still, an equal part of porter and stout … stout alone is too potent to admit of a full draught, from its proneness to affect the head; and quantity, as well as moderate strength, is required to make the draught effectual; the equal mixture, therefore, of stout and porter yields all the properties desired or desirable as a medicinal agent for this purpose.

“Independently of its invigorating influence on the constitution, porter exerts a marked and specific effect on the secretion of milk; more powerful in exciting an abundant supply of that fluid than any other article within the range of the physician’s art; and, in cases of deficient quantity, is the most certain, speedy, and the healthiest means that can be employed to insure a quick and abundant flow … The quantity to be taken must depend upon the natural strength of the mother, the age and demand made by the infant on the parent, and other causes; but the amount should vary from one to two pints a day, never taking less than half a pint at a time, which should be repeated three or four times a day.“

A mixture of stout and porter was originally known as “half-and-half”, a name also given to a blend of ale and porter, or “stout half-and-half”. From at least the early 1860s, the mixture was also known as “cooper”. The first known mention of “cooper” as a blend of “half stout and half porter”, otherwise “stout half-and-half”, came in John Camden Hotten’s Dictionary of Modern Slang, published in 1860. Two years later at Marylebone magistrates’ court in London a pub customer who explained “cooper” as “half stout and half porter” was corrected by the magistrate, who told him: ”That, I should say, is half-and-half”, suggesting the phrase was still not in common use. When Hotten brought out another edition of his slang dictionary in 1864, he added an explanation for the name: “Derived from the coopers at breweries being allowed so much stout and so much porter a day, which they have mixed sooner than drink the porter after the stout.

Other derivations have been suggested. John Bickerdyke (a pseudonym of the journalist and writer Charles H. Cooke), writing in 1889, and calling Cooper “a favourite mixture of modern Londoners”, said that “the best account of the origin of this name is one which attributes it to a publican by the name of Cooper, who kept a house in Broad Street, City … Cooper drank and recommended a mixture of porter and stout, the fame of which spread very rapidly. The combination became the fashion in the City, and finally it was brewed entire.” (There is, incidentally, little evidence that Cooper ever was brewed “entire”, that is, as a single drink, rather than being a blend of two already-brewed beers.)

Another supposed origin for the phrase was proposed by the Scottish journalist Andrew Halliday in an article written around 1863 in Charles Dickens’s magazine All the Year Round. Cooper, Halliday said, was named for the brewery functionary called the “Broad Cooper”, or abroad cooper, whose job was to inspect the brewery’s beer when it was in publicans’ cellars, to ensure that they were not adulterating it or watering it down. If the porter was indeed “below the mark”, Halliday said, the publican “slyly draws a dash of stout into it” to bring it up to strength, “and this trick is so common, and so well known, that a mixture of stout and porter has come to be known to the public, and asked for by the name of ‘Cooper’.”

One of the earliest advertisements for the drink appeared in 1862, when the Crown Brewery in Loam Pit Vale, Lewisham, on the edge of South-East London, was selling “Smee’s Half-and-Half (alias Cooper) Double Stout and Porter Mixed” at 10s 6d for nine gallons. The proprietor, Frederick Smee, also sold a typical line-up of 10 different ales, beers and stouts and porters, including two types of IPA, porter, single stout, Imperial Brown Stout, family ale, two types of mild ale and stock ale.

The following year a City wine merchant, Laidler and Fitch, of 52 Old Bailey, was advertising “Celebrated London Cooper” at 2s 6d for a dozen Imperial pints, no brewer named, and no explanation apparently necessary for what Cooper was.

In March 1862, the Cork brewer Beamish & Crawford signed a deal with a London beer bottler and wine merchant, Henry Hilditch Johnson, to export Beamish and Crawford beers to Britain and sell it at a price that would undercut Guinness. The Dublin brewery was now selling almost 242,000 barrels a year, of which 98,000 went to Great Britain. Beamish and Crawford in 1862 could only manage 94,000 barrels in total. The deal with Johnson would see the Cork Porter Brewery send him casks of year-old vatted extra treble stout, and porter, also known as single stout, to be blended and bottled at Johnson’s stores, the Circular Vaults in St Paul’s Churchyard in the City of London, and sold as Beamish & Crawford Cooper.

Johnson seems to have come up with another story to explain the name Cooper, which appeared in an “advertorial” plugging Beamish & Crawford‘s bottled cooper, originally in the Globe, London, and quickly reprinted in the Morning Post, Morning Advertiser and other London newspapers in November 1862. The report, supposedly repeating the words of a London omnibus driver, claimed that “old Jack Cooper, who used to drive one of the Bromptons” (a horse-drawn omnibus on the Brompton to Holloway or Islington routes) would always drink a glass of half stout and half porter when he pulled up at the White Horse Cellar in Piccadilly, one of the major coach and omnibus stops in central London, and “the potboy, seeing his ’bus pull up, would always sing out [to the barmaid], ‘Another glass of Cooper.’” Thus, it was claimed, the drink was given the name of the bus-driver.

Beamish & Crawford’s Cooper sold for 2s 6d per dozen imperial pint bottles, against the 4s per dozen charged in the London market for rival brands from Dublin such as Guinness and Robert Manders, and was advertised as “Bottled beer at draught prices.” The promotional campaign included a specially written song, “Where Do You Get Your Cooper?”, which, according to a handwritten note on a printed copy of the lyrics in the Beamish and Crawford archives in Cork, was sung by “Collins” — presumably meaning the era’s most famous stage Irishman, Sam Collins, best known for his rendition of “The Rocky Road to Dublin” — “and others at Dr Johnson’s [in Fleet Street], The Oxford [Oxford Street], The Frampton [Euston Road] and all other Concert Halls in London.” Given subsequent events, the claim, presumably by Henry Johnson, that a huge star of the stage was singing a promotional song for beer looks unlikely, at the politest, not least because “Where Do You Get Your Cooper?” was a terrible song. Its last verse went:

As it’s made in Cork it’s strong and light, not a headache in a puncheon;

A pint or two won’t hurt each day, before and after luncheon;

It’s the stuff to make you strong and cause a genuine sensation—

Beamish & Crawford’s Cooper’s safe to “Lick out all creation!”

Johnson had already failed as a wholesale tea dealer, in 1850, in a partnership with his father and brother, and been declared bankrupt. He had also failed as a hop merchant, with that business, Johnson and Hanson, collapsing in 1861. The deal with Beamish & Crawford quickly missed its expectations, despite the low price at which the cooper was being sold, and Johnson’s marketing efforts. He had told Richard Beamish that he would sell between 200 and 300 barrels in the first month of the arrangement, and increase sales every month after that. By September 1862 Beamish & Crawford were worried that sales seemed well short of target, but Johnson wrote to the firm insisting that he was selling 1,000 dozen pints of Cooper a week—equal to just under 200 barrels a month—and “before two months are out I shall sell 1,000 dozen a day.” In November, Richard Beamish traveled from Cork to London to check on sales himself, and found that Johnson had got rid of just 834 barrels in seven months, less than 40 per cent of the targeted figure. Beamish and Crawford had brewed 2,000 barrels of Extra Treble Stout for blending into Cooper in London, most of which remained unsold and “almost unfit for use.”

Back in Cork, Richard Beamish received an anonymous letter from London claiming that Johnson was filling empty Cork Porter Brewery casks with poorer-quality beer from the City of London brewery and sending them out as Beamish & Crawford porter, and topping up hogsheads from Cork with water and ullage (returned beer) from other breweries. Early in January 1863 Beamish wrote to Johnson telling him that the company would be ending its arrangement with him at the end of April, though he indicated that a new deal might be possible. Presumably thus encouraged, in March 1863 Johnson took out an advertisement in the Morning Post newspaper in London that seemed to blame any customer dissatisfaction with the beer he had been selling on an “unprecedented and suddenly increasing demand” for bottled cooper, which had supposedly “exceeded the most sanguine calculations.” Because of this, Johnson claimed, “it became for a short time absolutely impossible to keep up the stock in prime condition for immediate consumption. Many orders were declined, and others executed immediately after the Cooper was bottled, thereby doing great injustice to the quality.” The firm assured potential customers that “that difficulty no longer exists, a very large stock being now regularly kept in the primest possible condition.”

Even if this were true (and the surname Johnson does not inspire confidence ), Johnson’s business was running out of road. His partner in the firm, Henry Cremer, had left the previous August, presumably seeing the crash up ahead. On April 23 1863 Johnson was declared bankrupt, with net debts of almost £23,500.

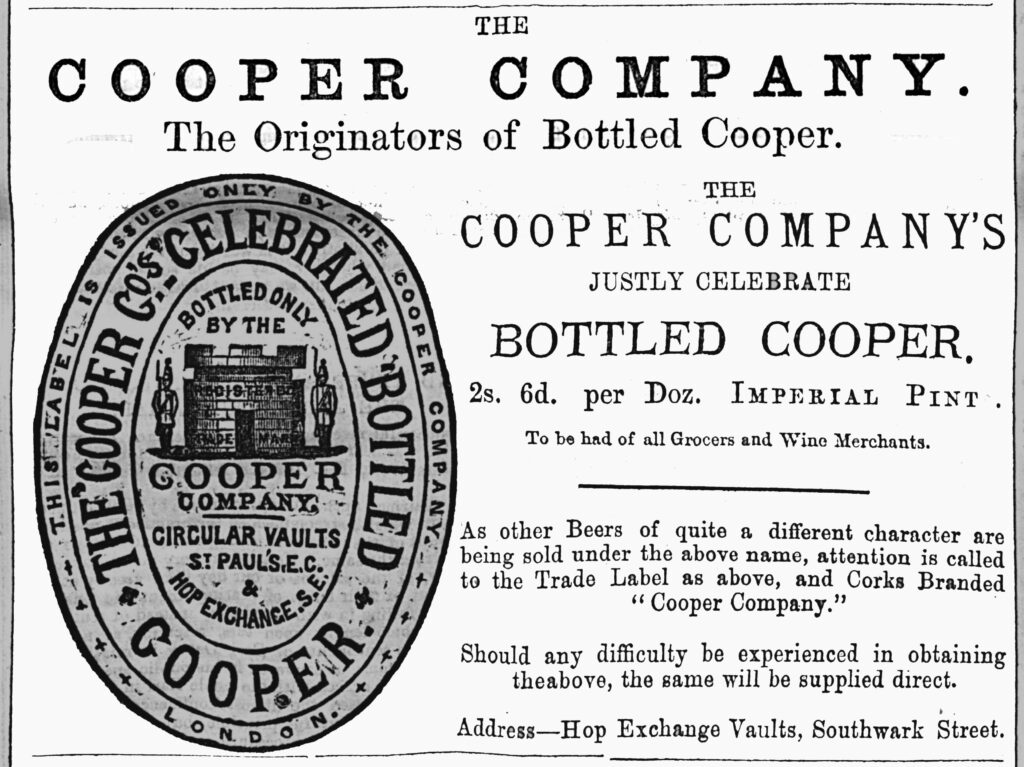

Three years later, in 1866, a firm called The Cooper Company arose like a phoenix from the Circular Vaults in St. Paul’s Churchyard, selling not just “The Cooper Company’s Celebrated Cooper” as 2s 6d per dozen Imperial pints, but also The Cooper Company’s Extra Treble Stout “for invalids” at 3s 6d a dozen, and The Cooper Company’s Strong Ale, Pale Ale and Family Ale, brewers all, again, unnamed. The firm used exactly the same trademark as Henry Hilditch Johnson, a castle with two armed guards, though apart from the trademark and the fact that it was using Johnson’’s old premises, no firm link between Johnson and the Cooper Company seems to be known. The company claimed in its advertising that “The term Cooper has been given to Stout which consists of Treble Stout and Single Stout,” and insisted that the Cooper Company “were the originators and are the only bottlers of ‘Bottled Cooper.’” Customers were warned to look out for “fresh brewed plain porter … sometimes … designated Cooper, a bad recommendation to the Genuine Article in one respect but a public recognition by the trade of its merits in another.”

The Cooper Company was still running in 1875, though it had moved south of the Thames to Borough in 1872, with its head office in the Hop Exchange Cellars in Southwark Street and “Export Cooper Cellars” nearby in Guildford Street. It was still claiming to be “the originators and introducers to the trade of bottled Cooper and Family Ale,” and advertised its Cooper as “not plain porter, under the assumed name of Cooper, but is what the Cooper Company originally professed it to be — viz., Dublin Vatted Stout and London Porter.” (If the Cooper Company was claiming descent from Johnson, this was, of course, untrue – the Cooper Johnson sold was a blend of Cork-brewed stout and porter.) The firm also sold pale ale, family ale, and “Mander’s” [sic] Invalid Stout from Dublin, suggesting that Manders’s brewery on the north side of St James’s Street in Dublin was also the source of the stout that went into the Cooper Company’s cooper.

Johnson, who was born in 1825 in Clapham, London, was still describing himself as a wine merchant, and based in Cannon Street in the City of London in 1868 when he registered “An Improved Mode of Advertising in Railway Tunnels and Cuttings”, which involved a series of illustrations, each changed slightly from the previous picture, to give the illusion of a moving picture to passengers zooming past in a train. Johnson’s “linear zoetrope” never seems to have gone into construction, and it would take another 120 years before a similar device to Johnson’s would be installed anywhere in the world.

Earlier, in September 1864 a wine merchant in Islington, North London was offering “The Celebrated Bottled Irish Cooper” at the usual 2s 6d a dozen pints, with potential customers told: “The term ‘Cooper’ has been given to Stout which consists of proportions of Treble Stout and Single Stout …” In the 1860s and 1870s Cooper was often sold by wine merchants, brewer unnamed, such as the “Extra London Cooper” on offer in 1865 from “sole agents” Henley and Son of Tooley Street, Southwark, “recommended for its purity, and free of that peculiarity identified with Irish beers.” Similarly a wine merchant in Lower Norwood, South London called Bennett & Co. was selling reputed quarts (two thirds of an Imperial quart) of Cooper in 1866 for 3s 6d a dozen, against 2s 9d a dozen for best porter and 4s 9d for Extra Double Stout, brewer(s) unnamed.

Another bottler, the Imperial Bottling Company, based in Henry Street, Bermondsey, South London, was selling “Scotch Cooper and Stout” (and “Scotch Dinner Ale”) in 1871, brewer unnamed. By 1872, however, the Imperial Bottling Company was selling “Lion Brewery Company’s Cooper”, presumably from the Lion Brewery in Belvedere Road, on the South Bank of the Thames, near Westminster Bridge.

Several small London brewers offered Cooper in cask: one was John Easterbrook, of the Gloucester brewery, Gloucester Road, Croydon, who advertised Cooper in 1873 at 10s 6d per nine-gallon firkin, halfway in price between his porter at 9s and his stout at 12s.

Bottled cooper had now begun to appear in London brewers’ price lists, not just in retailers’ offerings. Furze and Co. of the St. George Brewery, Whitechapel, East London was selling Cooper in 1868 at the standard 2s 6d for a dozen imperial pints. The next year Whitbread, which had only begun bottling its beer itself in 1868, announced the appointment of an agent, Robert Baker, to sell its bottled cooper, stout and ales. Its great London rival Truman Hanbury just under a mile to the east, was also retailing Cooper by 1870, again at 2s 6d the dozen. Combe and Co. of the Woodyard Brewery in Covent Garden, another big porter brewer, was offering London Cooper, London Stout and Extra Stout in 1872, all “Bottled at the Brewery Stores,” for 2s 6d, 3s and 3s 9d per dozen pint bottles respectively. By 1889 Truman’s was selling not just London Cooper, in corked or screw-stoppered bottles at 2s 3d per dozen pints, but Double Cooper at 2s 6d, alongside London Porter at 2s 6d, Brown Stout at 2s 6d, London Stout at 3s, Double Stout at 3s 6d, Invalid Stout, also at 3s 6d, and Imperial Stout at 4s.

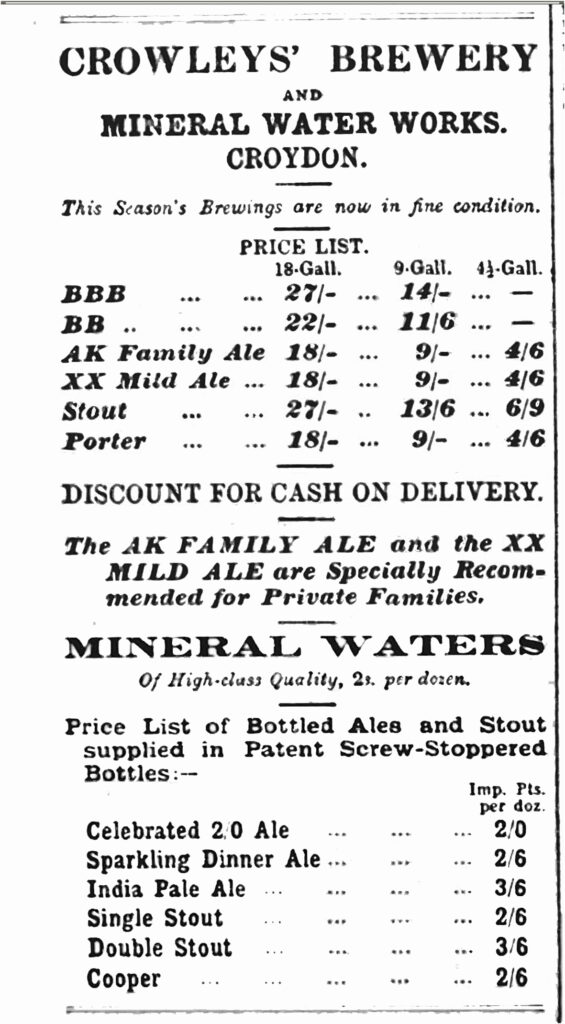

Whitbread, too, branded its cooper as London Cooper, from at least 1870. The mix was occasionally exported: by 1875 London Cooper (“A mixture of Ale and Stout”), bottled by the London Cooper Company, was on sale at five rupees, eight annas for a cask of three dozen quart bottles, in Bombay [Mumbai], India. Reid & Co. of Clerkenwell, another of the big porter brewers, was advertising in 1889 its “celebrated Cooper in Bottle of all Grocers and Wine Merchants, in small casks direct from brewery.” Crowley’s brewery in Croydon sold cooper at 2s 6d the dozen in 1889, alongside single and double stout; A. Gordon & Co. of the Caledonian Road, North London was offering it in 1891; Holt & Co.’s Marine Brewery in Ratcliff, East London in 1892; Henry Lovibond of the Cannon Brewery, Lillie Road, Fulham advertised bottled Cooper from 1893 while William Gomm of the Beehive Brewery in Brentford, Middlesex, was selling draft Cooper in 1895, its draft black beers helpfully labeled “P Porter”, “SP Cooper”, “S Stout,” and “DS Stout (for nursing)” at from 9s to 13s 9d per nine-gallon firkin.

The style also spread to brewers outside London in the surrounding counties. One of the earliest was the small Angel Brewery in Broad Street, Reading Berkshire, where Ferguson and Son were offering Ferguson’s Reading Cooper as early as 1869. By 1882 Ferguson’s larger local rivals, H. & G. Simonds, were selling bottled Reading Cooper as well. Benskin & Co. at the Cannon brewery in Watford, Hertfordshire had bottled Cooper in pints at the usual 2s 6d a dozen in 1886. Fremlin Brothers’ brewery in Maidstone, Kent sold bottled Cooper in 1890. Holmes & Co., which was running both the Greys Brewery in Henley on Thames, Oxfordshire and the Church Street Brewery in Stroud, Gloucestershire, 60 miles to the west, was offering Cooper alongside stout, mild ales and East India Pale Ale in 1891; Nicholson & Sons’ brewery of Maidenhead, Berkshire was selling bottled Cooper and Stouts in 1892, Ind Coope & Co. of Romford, Essex offered Cooper Special Stout in 1898 (alongside B.S. Nourishing Stout).

However, although Whitbread’s London Cooper was widely advertised as far north as Dundee, outside the South East of England brewers do not seem to have offered Cooper themselves. Gradually, in the first decade of the 20th century, even in London, Cooper faded out of the picture, along with the porter that was supposed to be part of its make-up. Whitbread’s Cooper appears in a price list issued by a West London wholesaler in 1913, at 2s 4d per dozen pints, but vanishes after that. A small Hertfordshire brewer, M. A. Sedgwick & Co. of Watford, was offering draft Cooper at 9s 6d a firkin in the same catalogue, with porter at 8s 6d and stout at 11s 6d.

A retailer in Gravesend, Kent in November 1915 was offering customers a remarkable range of bottled stouts, including Barclay’s London Cooper at 3s for a dozen pints, Barclay’s London Stout at 3s 6d, Luncheon, Nourishing, Invalid and Extra Stouts from the London & Burton Brewery Company of Stepney, East London at 3s to 4s, Fremlin’s Oatmeal Stout from Kent at 3s 6d, Mackeson’s Milk Stout at 4s 6d, the same price as Guinness, and Peter Walker’s Dietetic Stout at 3s 6d from either Burton upon Trent or Warrington. That, however, was about the last sighting of Cooper on sale anywhere. A style that had once been “a favorite of modern Londoners” had risen and fallen in little more than half a century.

Excellent piece Martyn, shedding more light on a little-known beer. Having written about Cooper myself in the past, I am pleased to think that your wider platform will introduce it to many more beer aficionados I first came across Cooper many years ago when Bill Wickett, the last Head Brewer at the Black Eagle Brewery, Westerham, gave me a Bushell, Watkins & Smith Ltd. Cooper label. At that time nobody seemed to know what Cooper was, so I was naturally intrigued.

Your usual meticulous research has built upon my piece for the Newsletter of the Brewery History Society (NL81, June 2018) and extended our knowledge of the style and of the promotional antics of Henry Johnson! If I might be permitted one tiny criticism… as a native of Croydon I know that until 1965 the town was in Surrey!

As a proud son of Middlesex, the “vanished” county, I appreciate your feelings. It’s always difficult, writing historical pieces, to know whether to use the “old” county names opr not, a bit like not knowing whether to write about the East India Company sailing to Bombay or Mumbai.

Martyn what was Luncheon stout?

Another remakable, and fascinating, piece of research on a beer style that many, perhaps most, of us have never even heard of.

Lots of good stuff in there.

From looking at lots of price lists, in many cases Cooper just looks like bottled Porter. The Crowley’s price list in your post is an example. Porter and AK are both 18/- a kilderkin, and what I assume are the bottled versions, Sparkling Dinner Ale and Cooper are both 2s 6d per dozen. The bottled Stout must have been the same as the Porter, too, as the prices are the same.

Porter was a bit like Mild and after a certain point the name was rarely used for a bottled beer.

I’m sure you’re right, Ron

[…] Zythophile Martyn Cornell has written about London Cooper, a briefly trendy mix of stout and […]

“and porter, also known as single stout”

Were these names truely interchangeable? I always thought that single stout or stout porter was one step higher on the gravity latter than porter.

It depended on the brewery. Guinness, for example, referred to its single stout internally as porter.

I see. Thanks for the clarification!

I would add that Cairnes used single stout for it’s weakest and double stout for the stronger version.

I have an Original Poster c 1890 – 1910 for Bottled WHITBREAD COOPER . Sorry can’t post a picture because you don’t seem to offer that function , Cheers

You can email it to me at mcorn311@gmail.com, Ross, if you like …