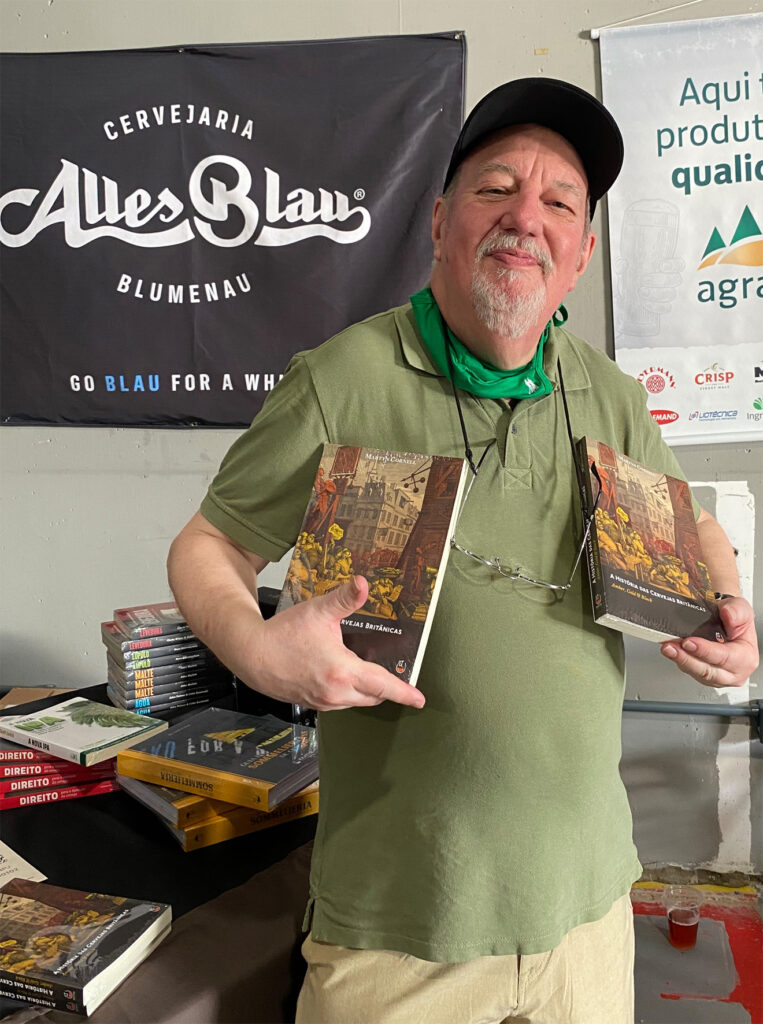

It’s not that they’re chanting my name in the favelas of Rio, or painting my portrait on walls in Salvador. But I don’t get dozens of people at a time in Britain queueing up to get me to sign a copy of my latest book, and have a selfie taken with me, Britons by the score have not been sending me friend requests on Facebook in the past month, unlike Brazilians (I’ve put on more than 50 FB friends since February), and only in Brazil have I given four talks in nine days to attentive audiences eager to hear what a fat elderly Englishman has to say about the history of IPA, or the Fuggle hop, or British beer in general.

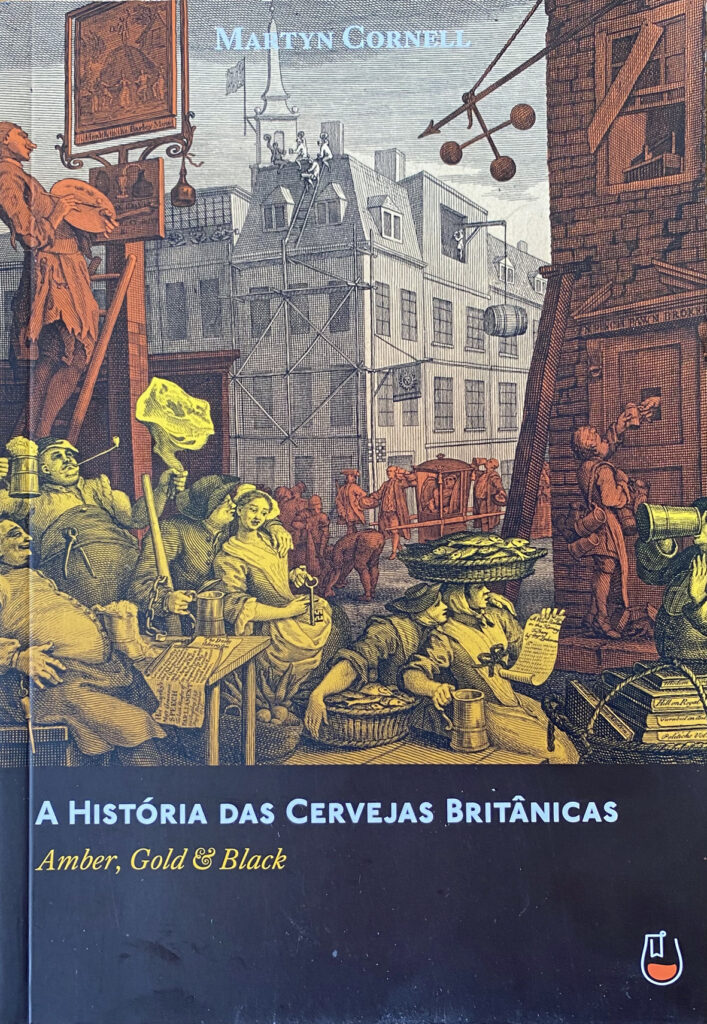

All this sprang out of the publication of a Portuguese version of the book I wrote back in 2010, Amber Gold and Black, which was the first ever history of British beer styles, from porter to bitter to Burton ale to mild. AGB has been out of print for five years or so now, and if you want a second-hand copy you won’t find one for sale for less than £60: the Kindle version is still selling steadily, and brought in £150 in royalties in the last tax year, which for the electronic version of a 12-year-old book on the history of beer is pretty good, I think. (It is, incidentally, the only book I have written that never won anything in the BGBW awards: to all those who whinge on about how unfair awards are, it’s great to win them, but the best indication of a book’s worth is continuing sales, not awards.)

Editora Krater, a publisher specialising in books about beer, based in São Paulo, Brazil, contacted me last year about the possibility of bringing out a Portuguese version to take advantage of the growing craft beer scene in Brazil, and the big interest among Brazilian brewers in historic beer styles from around the world. I, of course, said yes straight away, and the result was that, since I had been invited to be a judge at the 2022 Brazilian Beer Contest, South America’s biggest beer competition, with more than 530 breweries and 3,600 beers, which takes place in Blumenau, the “beer capital” of Brazil, and I was also a speaker at the International Beer Conference which was happening right after the beer judging, it was decided that this could be combined with several “personal appearances” to launch the book, in Blumenau and São Paulo.

So: why the big reaction in Brazil to the appearance of a translation of a 12-year-old book about British beer styles and their history? The answer is that many Brazilians today are hugely enthusiastic about beer outside the bland mega-lagers, and eager to learn more: they are sure they don’t know enough, and they turn to books like mine to teach them, mostly because there are very few other similar resources telling you just exactly how, in detail, porter developed over the centuries, or modern milds grew out of much stronger, paler ancestors. And when I say “very few”, I mean “In Portuguese, exactly none.”

Sure, if you want to know which 999 beers to drink before joining AlAnon, or what foods to pair with an obscure Pyrenean wheat beer made with Andorran pine nuts, you have a wide choice of books to read, even in Brazil. In-depth beer history, not so much – and Brazilian beer enthusiasts turn out to have a delightful thirst for just the sort of stuff I can supply. In Britain, however, most beer drinkers think they already know enough about the history of the beers they drink not to need to buy any more books about the subject, just as any German or Czech beer drinker believes their beer knowledge is as good as it needs to be, or any French drinker thinks they already know everything they need to about wine.

Of course – and I’m not just saying this because I want to sell more books and articles about beer history – most British beer drinkers (and American beer drinkers), even those who think of themselves as experts, don’t know anything like as much about beer styles, and particularly the history of beer styles, as they think they do. For any British beer drinker over 40, in particular they almost certainly received their beer history education at a time when the big myths were still unchallenged, so that they probably still believe that porter was first brewed in 1722 to replace a beer called three-threads, and India Pale Ale was invented by a man called George Hodgson, who brewed it extra strong because weaker beers would not survive the journey east. All untrue, as regular readers of this blog know.

I’m far from the first British beer writer to have a Brazilian edition of one of their books published, I must stress. Tim Hampson, Mark Dredge (who is, I note, currently number two in the “drinks” section on Brazilian Amazon with his Cerveja E Gastronomia), Melissa Cole, Zak Avery and, of course, Michael Jackson have all been published in Portuguese in Brazil, and so have plenty of Americans, including Randy Mosher, Garrett Oliver and Stan Hieronymus.

Can I also interject here that I do recognise how incredibly lucky I am. I shall be 70 in a couple of months, and yet a few weeks ago I was standing in a Brazilian craft brewery telling an audience of 40 or more attentive Brazilians the history of Indian Pale Ale. Who knew a nerdish obsession with ferreting out the obscurest, and sometimes dullest of facts about a subject that is extraordinarily far down the list of Most Important Topics in the World Today could take you so far – 6,000 miles, in this case, that being the almost exact distance between my home and São Paulo.

The Brazilian craft beer scene is tiny compared to the overall beer business in the country, which is dominated by big brands such as Skol and Brahma, and the enormous AmBev, part of AB InBev, largest brewer in the world. But it is wildly enthusiastic and throbbing, and producing a fascinatingly wide range of beers, many using local ingredients such as the many fruits only found in Brazil, and woods from native Brazilian trees that give fascination flavours to beers matured in them. They are, however, also hugely interested in European brewing traditions. The overall winner of the Blumenau beer contest was a Brazilian-brewed Grodziskie, a Polish style of low-alcohol smoked wheat beer from the town of Grodzisk that died out earlier this century and was revived by Polish craft beer enthusiasts. I doubt many craft beer brewers in Britain have heard of it.

I was pretty uniformly impressed, again, as I was when I first came to Brazil in 2020, with the very high standard of almost all the beers I drank in bars and at breweries, and delighted to make my acquaintance, again, with Brazil’s home-grown beer style, the Catharina Sour. Neither sour beers nor fruit beers are high on my list of favourite styles, but this combination of fruit – anything from pineapple to cashew berries via guava and mango – with a kettle-soured wheat beer rarely seems to be other than excellent in Brazilian hands, combining tartness, sweetness, full fruit flavours and depth. I was also delighted to meet Alexandre Mello, now head man at the Alles Blau brewery near Blumenau. (“Alles Blau” is a jokey translation into German of the Brazilian Portuguese expression “tudo azul”, literally “all blue” but meaning “all’s well” – Blumenau was heavily settled by German immigrants in the 19th century, hence its long involvement with the brewing industry.) Alexandre was one of the people, together with the cousins brothers Fernando and Carlo Lapolli, and Nuno Silva, who developed the original, ur-Catharina Sour, which was released commercially as Sun of a Peach by Cervejaria Blumenau. He told me the true origins of the style’s name, which I’m not going to tell you because I’m saving it for a book, but let’s just say it’s not the version you’ll read elsewhere.

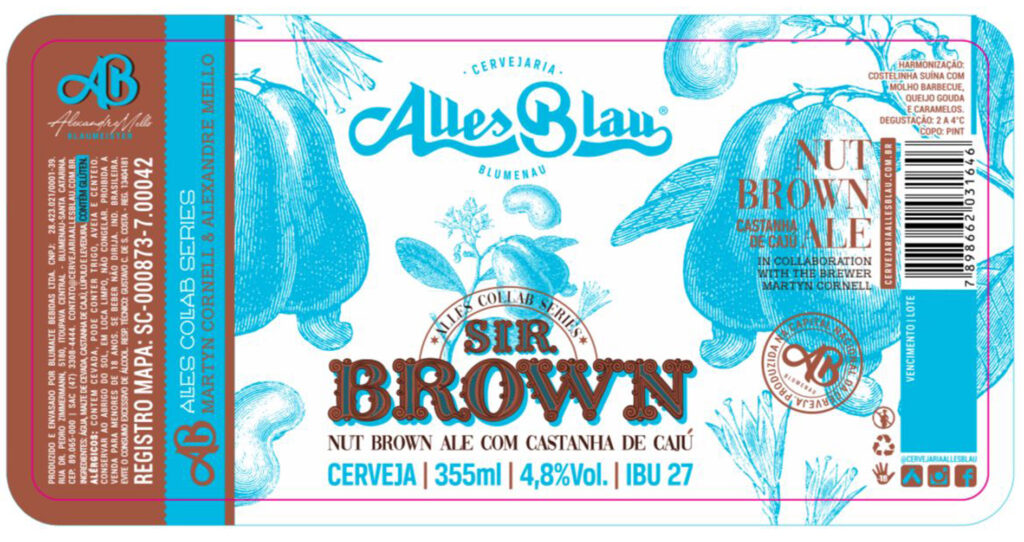

Alexandre had invited me to put together a recipe for an Anglo-Brazilian collaboration, to honour the launch of my book at the Alles Blau brewery. I was hoping to make a Catharina Sour with Fuggle hops in, to mark the 150th anniversary of the first harvest of Fuggle hop this year, but that would have taken too long to organise, because of the kettle souring element. Instead we decided on a “Brazilian nut brown ale” including Maris Otter malt from Crisps in Britain and 25kg of toasted cashew nuts, with – well, Alexandre couldn’t source any Fuggle hops, so he used Willamette instead, since Willamette is basically a triploid version of the hop the Fuggle brothers pioneered back in the early 1870s. I have no idea whether I will get to try any of the finished beer, but I did get to taste the wort, which was nicely nutty.

I barely touched on the beery attractions of São Paulo in my couple of days there, but I thoroughly enjoyed meeting Junior Bottura, founder of Cerveja Avós (which translates as “Grannies’ brewery”, very roughly), another hugely enthusiastic brewer, who has a great little brewpub/restaurant on the Rua Croata serving excellent beers – can’t recommend it highly enough. I also loved another brewpub, Cerveja Croma, on the Rua Harmonia in Vila Madalena, SP, which knocked my trainers off with a deep red brew called Brazilian Storm, made with açaí berries, banana and “Frutas Vermelhas” – red fruits. This 7 per cent abv beauty is described as a “smoothie-style sour”, a phrase that would normally have me clutching desperately at the cross and garlic in horror. It was, however, absolutely delicious, dry, fruity and a great end to a meal: a tremendous advert for the idea that if you know what you are doing – and Brazilian brewers clearly do – heavily fruited beers can work very well indeed.

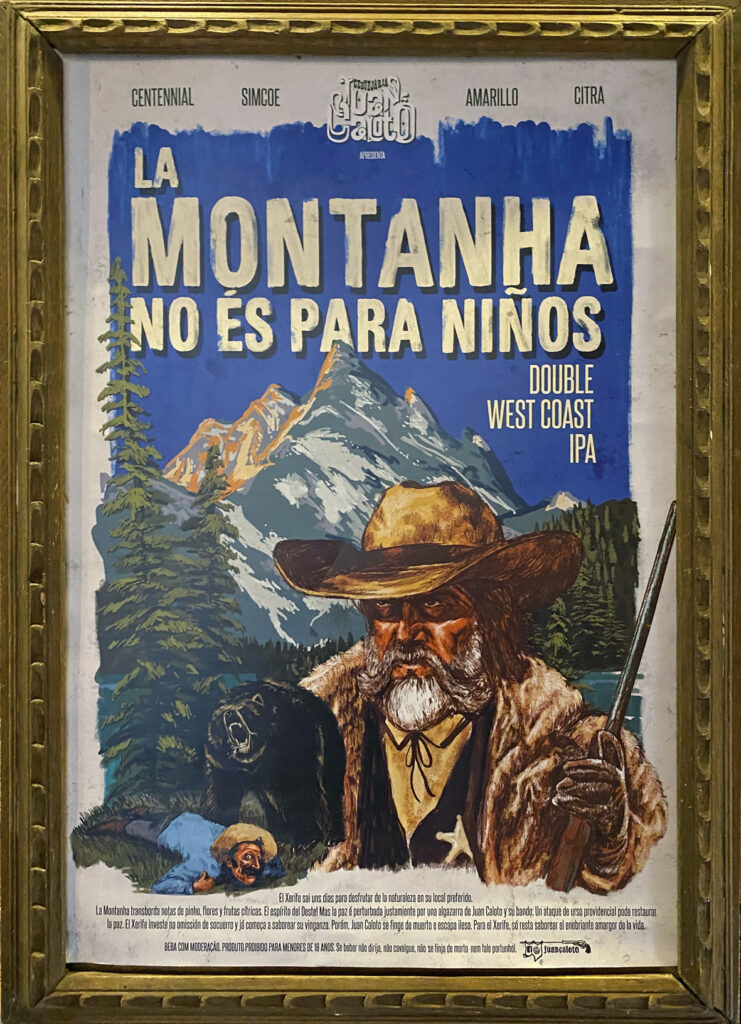

My third top tip is Esconderijo Juan Caloto, “Juan Caloto’s Hideout”, on Rua Gandavo, run by the gipsy brewery Cervejaria Juan Caloto. The theme here is “spaghetti western”, riffing off The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, and all the signs, posters and marketing are done in a deliberate mixture of Spanish and Portuguese – Spanguese, if you will, Spanish words with Portuguese endings and vice-versa – that both Spanish speakers (who call the mixture Portuñol) and Portuguese speakers (who call it Portunhol) find hilarious: think Franglais. The marketing may be jokey, but the beers are very good, and for reasons I’m really not sure about this was the bar most like a pub that I have found in Brazil so far: possibly, I think, because it is, or certainly looks like, a converted home.

I learnt, as usual, a vast amount on this trip, including the fact that in Brazilian Portuguese, “Oi!” is the equivalent to “Hi!”, so that you will hear people on the phone saying “Oi!” to each other. Brazilians were amused to learn that if a Londoner says “Oi!” to you, it contains a considerably more aggressive aspect than it does in Rio or São Paulo – ie, a punch in the maaaf is most likely only a short time away..

For the sake of openness, all flights and most of the taxis on this trip were paid for by me, including the extra ticket I had to buy after LATAM, the evil bastards, cancelled my booking on one leg of the journey without telling me or offering any explanation. Accommodation and most meals were paid for by either Concurso Brasileiro de Cervejas Blumenau or Editora Krater, to whom my very grateful thanks. It was huge fun meeting up with old pals – Tim Webb, Ron Pattinson, Susan Boyle, Chris Flaskamp of the Tübinger brewery in Chile, to name only a few. In particular I’d like to thank Doug Merlo of CBC for inviting me back to be a judge again, Diego Masiero of Editora Krater for being a great companion and an impeccable host, all the other Editora Krater people I met, for the free T-shirts especially, and all the many Brazilian beer fans and brewers who treated me with such hospitality, friendliness and enthusiasm. Eu vou voltar!

You’ve no doubt covered this elsewhere but is there any chance of a UK reprint of Amber, Black and Gold, perhaps in larger type? Or would folks be better off with the Kindle edition on both counts?

While AGB stands up remarkably well after 12 years – in my opinion, at least – I’d rather do something radically different the next time I tackle the history of styles, I think, rather than a reprint …

why is that? and how radically?…..(I have AGB and is my reference book when I am quoted “facts” on history of IPA…..surely AGB warrants a reprint)

Never mind blogging, writing a book is clearly the key to international (or at lest Brazilian) fame and recognition. Might give it a bash some time – how hard can it be? (Joke.)

Just for the record, the much-missed* Ticketybrew made a Grodziskie. I had a 330 ml bottle of it once, about half of which threw itself out of the bottle with some force as soon as I opened it. I don’t think it ever made it to large-scale production, possibly for that reason. Nice beer, though.

*if only by me

Great write-up!

Do you happen to know if the edition will get distribution in Portugal?

Cheers,

Alex.

No, but I’m sure Editora Krater will be able to tell you

The new cover is great. Ah it’s entirely Hogarth’s “Beer Lane”.

If you make a few corrections and re-publish, I’d probably by a second copy 😉

Ah, correction, “Beer Street”. I certainly mashed that up.

“Alles blau”, in colloquial German could, at a pinch, mean “They’re all hungover”.

Probably just a coincidence.

Hmmmm …

It actually means “All drunk/sloshed/hammered” in colloquial German. But I’m sure the Brazilians meant it to be a pun on the Brazilian phrase “Tudo azul” meaning “all great/thumbs up” (like Martyn says in the write-up). It does add another interesting variable, though, especially for my German friends when they see me wearing the brand’s hat. Cheers!

Yes, you’re right. I must have had a little brain fapse there, confusing the event with it’s aftermath. Personally I blame the fact that I haven’t been to Germany (or Austria) for over two and a half years (the longest period in my whole life) due to you know what.

Nevertheless, it is a jokey beer-related reference to the fact that a very similar phrase means two different things in German v Portugese. It’s not exactly a pun, but we agree that it’s an intentional cross reference.

Sorry, addendum – when I said “probably a coincidence” above, I was being a bit ironic, as Martyn recognised – it is obviously a deliberate reference to the (actually rather dated but never mind) German phrase, as you say.

Fun! Especially in a country where what is now ABInBev made big money with selling cheap beer that was advertised to drink as cold as possible (somewhere in the second half of the nineties I think).

70s, 80s and 90s…until today actually. Craft beer, with over 1,500 breweries, accounts for only 1-2% of the market…dominated by 3 giants.