There are many dozens – probably hundreds – of brewing traditions around the world, from the umqombothi of South Africa to the tiswin of the Apache, the kveik beers of Western Norway to the chicha of Latin America. Most are pretty much unknown to the barley beer drinkers of the Western European tradition. Few are more obscure than the beers of South East Asia. Did you even know that there is a long tradition of local beers made with local ingredients among the many peoples of South East Asia? Now a bright light has been shone on one country, Myanmar, with a book that celebrates a host of different local beers, wines and spirits lovingly and carefully made from rice, from sorghum and from millet using traditional ingredients, flavourings, techniques and knowledge handed down from mother to daughter (mostly), in villages across the country and consumed for the sake of pleasure, of custom and of conviviality by family, friends and neighbours.

The author of Heritage Drinks of Myanmar, Luke James Corbin, could not come from a better background, having studied anthropology at the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific in Canberra and then worked for Burbrit Brewery, a craft brewer in Yangon, Myanmar. Backed by dozens of excellent, evocative photographs from Shwe Paw Mya Tin, Corbin dives into descriptions of how each drink is made, with a brewer’s eye on the techniques and technology, and an anthropologist’s take on the place of these drinks and their brewers and makers, within the societies that make them and drink them

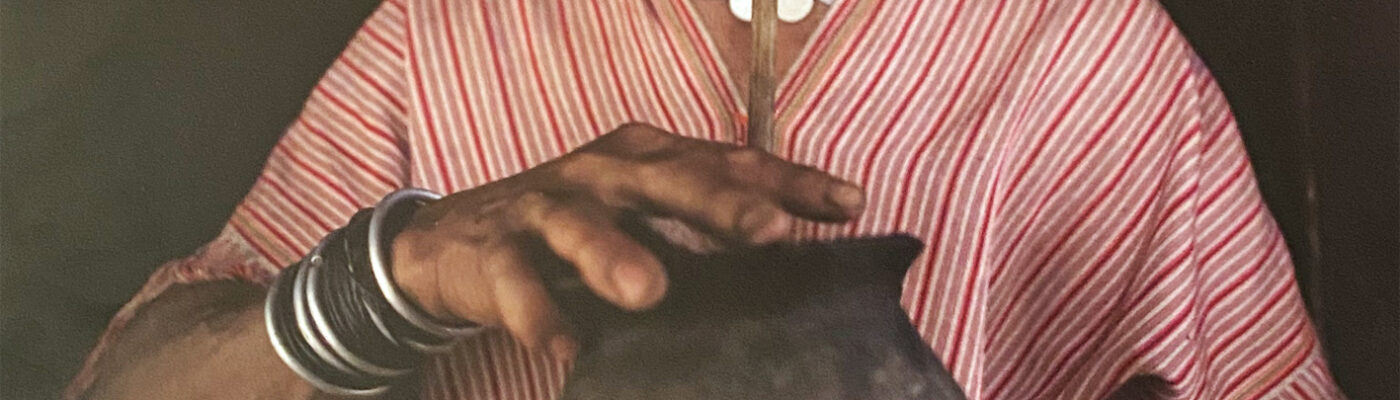

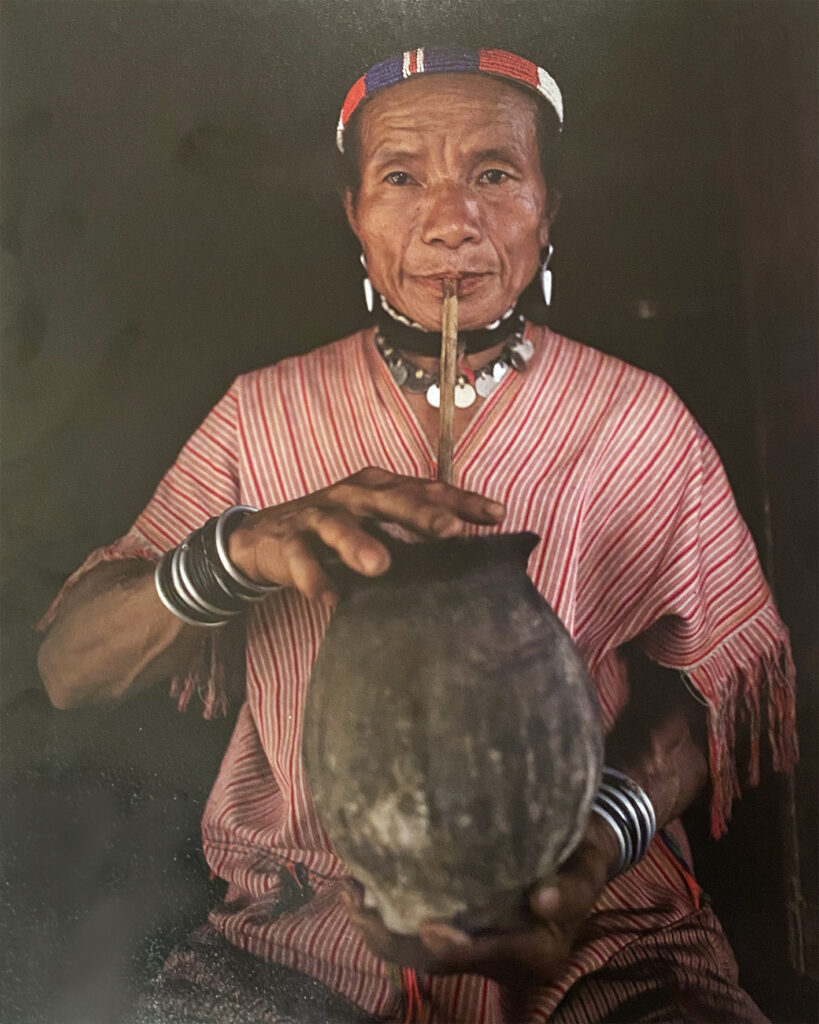

It is important not to exoticize these drinks. OK, that woman drinking chiya sorghum beer through a straw from a warm clay pot may be wearing rings that, to your eyes, make her look as if she has a strangely stretched neck, and that lout khu rice spirit may be flavoured with caterpillar fungus or infused with bees. But to the people with the neck rings, or drinking alcohol with bees in it, this is everyday stuff. Don’t judge others by your norms, Norm.

Corbin takes care to say that the drinks featured in the book, seven beers, five spirits and two wines, are not “a selection of the most peculiar or most representative” drinks to be found in the Golden Land, but “an attempt to balance breadth with depth”.

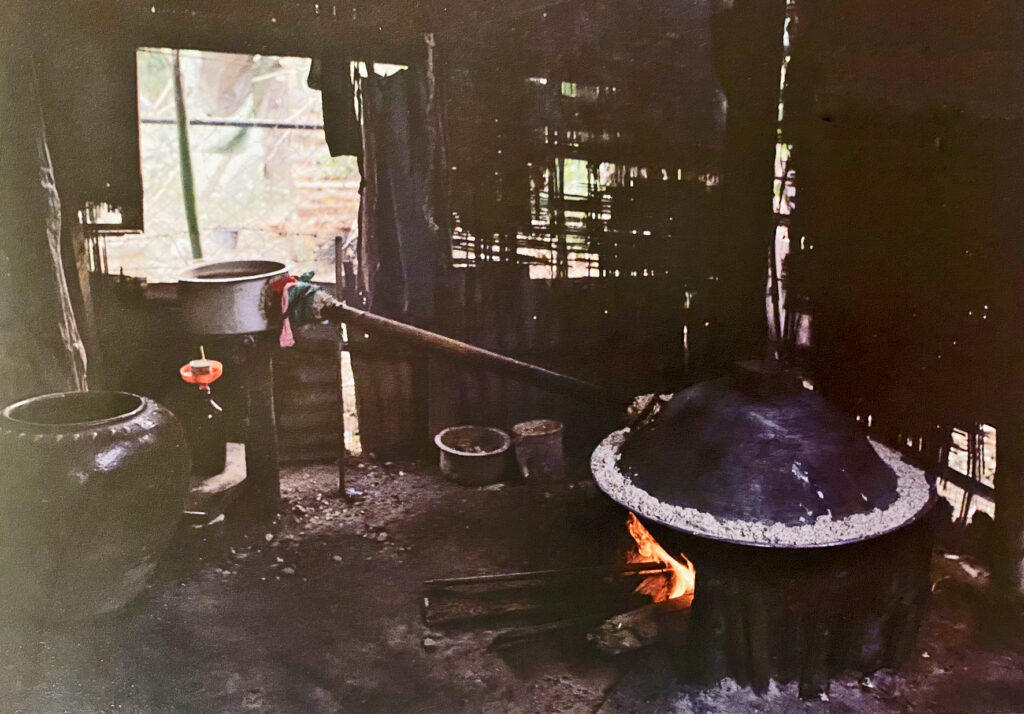

I could quote extensively from every single story, but let’s just concentrate on two or three. Hpwe ayeq is a rice spirit infusion from Northern Kayah State. In the village of Moe Bye, home mostly to Kayan people, nearly every household makes rice beer, but only a few take this one step further to produce te, a clear spirit distilled from this rice beer. The spirit is made from local broken rice, boiled until completely cooked, spread on a wooden table and left to cool. Yeast cakes, made from soft grain rice inoculated with a family strain of yeast, are then pounded and sprinkled over the grains. The yeast and cooked rice is then placed in clay pots and left to ferment for several days. The resultant creamy white rice beer is then distilled in a double-pot still, by being gently heated in the first pot, with the alcohol vapours running down into the second pot, filled with water, where it condenses and drips from a spout into a bottle.

Some of this spirit is infused with local herbs and flavourings, and one version, hpwe ayeq, is made with the assistance of the hpwe, the local name for a type of mole that collects plants it then carries back to its underground den. Hunters track the hpwe‘s molehills, dig down, and remove the herby contents in a sack, preferably after they have been underground for at least a month in a moist, warm environment that softens the plants and makes them particularly fragrant. The herbs gathered from the hpwe‘s den are then infused in the te for several weeks, turning the spirit a rich amber-red. On ordinary occasions the regular te is drunk without any infusions, but when guests arrive, or on special occasions, the hpwe ayeq is brought out. The philosophy behind the drink is that the hpwe is a healthy, thriving animal, and it naturally chooses the best herbs and plants to keep its den healthy.

Tar san ron, or red millet beer, is made by the Mwim, a group of Chin people in Mindat district, southern Chin State, in the north-west of Myanmar. In Chin State each village household is more likely to brew than not, and different households often maintain their own yeast strains. The Mwim use red millet to brew with because of its flavour and its ability to make a beer that stays fresh longer. The millet grains are harvested and dried, and then boiled slowly in a metal pot. The cooked millet is spread out on bamboo mats to cool. A yeast cake is then crushed and sprinkled over the grains. Each household, in the past, would prepare its own yeast, making a yeast cake from sticky rice into which part of an older yeast cake has been pounded, mixed with herbs and spices. The creamy brown mixture is formed into cakes, sprinkled with more old yeast and covered with banana leaves for two nights. The yeast cakes are then dried until they turn white. Today brewers will swap yeasts and sometimes use a mixture of different yeasts collected from neighbours. Men are not allowed to touch the yeast.

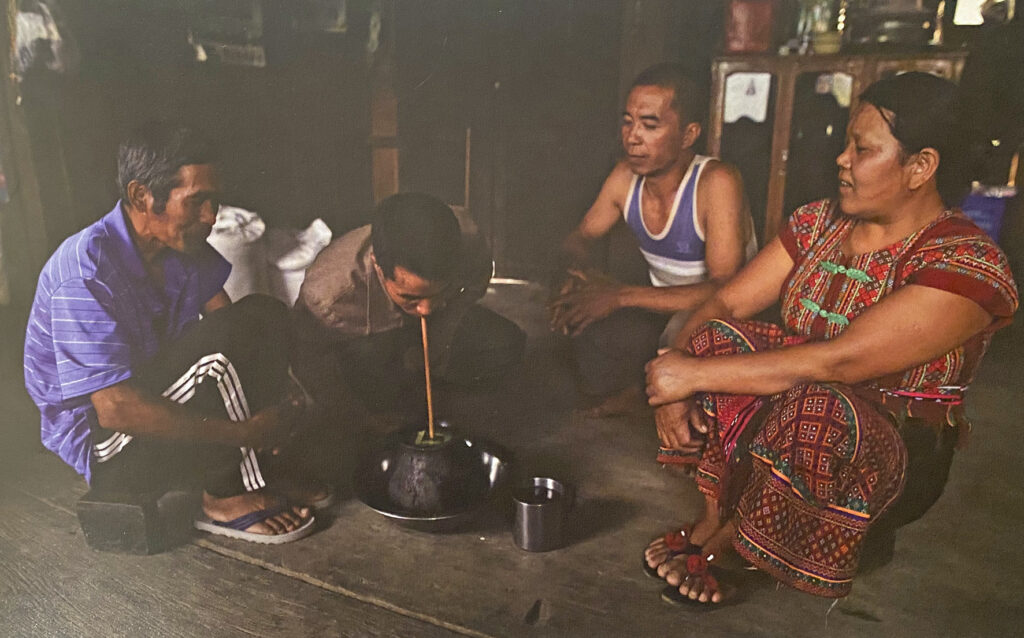

The yeast-and-millet mixture is transferred into a clay pot and covered with dry leaves – banana, mango or custard apple – and left for two weeks to a month. One ready for serving, the tar san ron is drunk from cups made from the horns of oxen, or from gourds, or from a communal pot through a filter straw. Tar san ron is both an everyday drink and a drink for festivities, funerals, weddings and housewarmings.

Many people in Myanmar make chiya, or sorghum beer, and it is a speciality of the Kayah, otherwise known the Red Karen, of south-west Kayah State. Sorghum beer is, of course, found widely across East and South Africa. As in East Africa, the Kayeh sip their sorghum beer through a straw from clay pots that are swimming with grains. (Drinking beer through straws, or reeds, from a pot is a tradition that goes back to the Sumerians around 4,600 years ago.) Only women make chiya, and mothers pass their brewing techniques on to their daughters. Kayah brewers boil sorghum grains for at least an hour, until they become sticky. They are then spread on mats and cooled, after which a yeast cake is mixed in with the grains. The grain-and-yeast mix is then put into a fibre basket and left for two days. When ready – often after a white fungus has spread over the top of the grains – the mixture is placed into a clay put, which is sealed tight. The final fermentation takes five to seven days. Chiya is drunk daily, with food such as roast chicken or pork, mostly by men, but it is also consumed at celebrations, wedding and funerals, and given as a gift. Chiya is economically important enough that whole villages grow sorghum just to supply the needs of brewers.

All these different ways of making intoxicating drink, in a country with a population about the same as that of England, reflecting traditions that go back certainly hundreds and probably thousands of years, suggest a multitude of fields of study. What light do the brewing and drink consumption traditions found in Myanmar throw on the likely brewing and drink consumption traditions found in Europe a thousand and more years ago? Even more interestingly, what organisms are found in those yeast cakes? Is it our old friend Saccharomyces cerevisiae? Surely … but if it is, how does it relate to the yeast found in Europe? And how do the yeasts found in, say, Chin State relate to those found in, for example, Kayah State?

I cannot recommend this book highly enough for anyone interested in beer, or in alcohol, outside the comparatively narrow traditions of modern Europe and urbanised North America. Corbin and his colleagues must be congratulated for giving us an essential insight into a set of traditions and drinking cultures that, while alive and mostly well, are still under threat from Western wines, beers and spirits – and well done Pernod Ricard Asia for sponsoring the book, and acknowledging in a foreword the value of these traditional cultures, and the convivialité they encourage. The original Myanmar government sponsors of the book are all now in jail, as a result of the coup of February 2021, which put the Myanmar military back in control of the country, and forced Luke to pull the book from its original publisher in Myanmar, find a new publisher in Thailand, and completely alter several sections.

Almost 80 years ago my father was in what was then still called Burma, aged 22 or so, with the Imperial Japanese Army lobbing mortar bombs at him and his fellow Chindits. Did he, while he was there, drink any of the beers in this book, or any like them? I would not be surprised. I would love to travel to the country, and try some myself, though with a military dictatorship currently in charge that is not going to happen soon.

As well as being rammed with fascinating facts, the book has been produced to a very high standard: the production values are excellent. It’s not cheap – $65/£52 a pop – but for UK/EU buyers, at least, while it remains in pre-order only, you can get 30% off using the coupon code “CSFS2022” You can pre-order it for UK/EU delivery using this link. Unfortunately the Ukraine War has sent freight charges soaring 400%, so no copies are being shipped in bulk to Europe or the US. For ordering, therefore, use the Silkworm Books website. I’m not sure if in North America the book can still be pre-ordered through the University of Washington Press –it’s on page 43 of the Spring 2022 catalogue.

What a great read – thanks Martyn.

Another great story! Well done Martyn!

Thanks for sharing Martyn! Was lucky to meet Luke during his days with Burbrit in Yangon. Good ol’ days… The latter is the first craft brewery in Myanmar

Fascinating article, Martyn! Thanks for story.

Well you’ve sold one book (once I figured out how to order it…)

This sounds lovely.

Ordered a copy via combinedacademic.co.uk a few days ago but just received a message that they can’t supply the book and are returning the payment.

So you might want to take their sourcing link out of the text.

Hope to order it elsewhere soon!

I’m trying to find out from the author what is going on …

Blame Putin for a huge leap in freight charges, which makes it uneconomical to ship in bulk from Thailand. You can still order through the Thai publisher’s website, https://silkwormbooks.com/collections/frontpage/products/heritage-drinks-of-myanmar

Sorry to say – the publiser cancelled the order, the book is not being published.

I’m trying to find out from the author what is going on …

Blame Putin for a huge leap in freight charges, which makes it uneconomical to ship in bulk from Thailand. You can still order through the Thai publisher’s website, https://silkwormbooks.com/collections/frontpage/products/heritage-drinks-of-myanmar

Another amazing reason to come back to Myanmar! Thank you, Martyn!

[…] Traditional brewing in Myanmar: an amazing heritage […]