It’s a small error, as they go, but it has been around for at least 40 years, and it appears everywhere from Michael Jackson’s World Guide to Beer to the labels on bottles of Harvey’s Imperial Extra Double Stout, so let’s try to stamp it to death: Albert Le Coq was NOT a Belgian.

Le Coq is remembered as a 19th century exporter of Imperial stout from London to St Petersburg, whose firm eventually took over a brewery in what is now Tartu, in Estonia to brew Imperial stout on what was then Russian soil. The brewery is still going, it took back the name A Le Coq in the 1990s, and an Imperial stout bearing its brand has been brewed since 1999, though by Harvey’s of Lewes, in Sussex, not in Estonia. But every reference to the company founder, Albert Le Coq, apart from in the official history of the Tartu brewery – which is almost completely in Estonian – says he was a Belgian. He wasn’t.

In fact the Le Coq family were originally French Huguenots, who had fled to Prussia in the 17th century from religious persecution in their home in Metz, Lorraine, after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV in 1685. They prospered in their new home, operating mostly as merchants, though one, Paul Ludwig (or Louis) Le Coq, (1773-1824), the great-grandson of Jean Le Coq, born in Metz in 1669, rose to be chief of police in Berlin. It looks as if Paul had a brother, Jean Pierre Le Coq (1768-1801), born in Berlin, who was a merchant in Hamburg, and his branch of the family also became wine merchants, owning a winery in Kempten, near Bingen, on the borders of the Prussian Rhineland.

The year before Jean Pierre died he had a son, born in Berlin (although some sources say Bingen), called Jean Louis Albert, who became better known under the German version of his name, Albert Johann Ludwig Le Coq. Plenty of sources going back to at least 1939 claim the family company was founded as A Le Coq & Co in 1807, when Albert was just seven years old: there seems no documentary evidence of this, however. Nor is it clear when, and by whom, the wine business in Kempten was acquired. At any rate Albert was living in Kempten in 1827, when his eldest child, Andreas August, was born there.

Some time in the 1830s Albert Le Coq moved to London, apparently to develop a trade in Britain for the family wine business. In 1851 Albert claimed he had been living in England for 20 years, implying he moved to London in 1831, though the births of all his children up to the youngest, Molli, born 1836 in Frankfurt, were in the same region of Germany as Bingen. Albert was certainly settled in London by 1841, when the census found him living in Mornington Crescent, St Pancras. He had probably been in business in Britain for some time, however, for the partnership of Albert Le Coq and Charles Seidler, merchants of Mark Lane in the City, operating as Le Coq & Co, was dissolved “by mutual agreement” on July 1 1841. Within a few years, of this, if not before, Le Coq had expanded from wine into exporting beer, not just stout but, surviving bottle labels show, pale ale, to Danzig, Riga and St Petersburg. One source suggests the trade was prompted by the opportunity to fill the holds of the returning fleets of ships were now coming the other way, from the Baltic to Britain, with cheap, high-quality barley from Livonia (covering parts of modern Latvia and Estonia) after the abolition in Britain in 1846 of the Corn Laws, which had previously placed high tariffs on imported grain.

Strong stout had been exported from Britain to Russia since at least the late 18th century, notably by Barclay Perkins’s Anchor brewery in Southwark, earlier known as Thrale’s. The landscape painter Joseph Farington wrote in his diary for August 20 1796: “I drank some Porter Mr Lindoe had from Thrale’s Brewhouse. He said it was specially brewed for the Empress of Russia and would keep seven years.” The average imports of porter and English beer into St Petersburg between 1780 and 1790, according to William Tooke, writing in 1800, were worth 262,000 roubles a year, when the rouble was five to the pound sterling. In 1818 almost 214,000 bottles of porter were exported to St Petersburg, with the figure for 1819 being just under 122,600 bottles.

From early on, Le Coq exported beers to Russia in bottles embossed with the firm’s name, bottles which the Russians were happy to recycle: according to Ronald Seth, writing in 1939, the first Russian wines from the Caucasus ever seen in Britain, on show at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park in 1851 as part of the Great Exhibition, were in repurposed A Le Coq beer bottles. The Crimea War, which lasted from 1853 to 1856, put a short stop to exports to Russia, but at the end of the war, again according to Seth, Russian officers entertained their British guests at Sevastopol with A. Le Coq porter.

Albert settled in England firmly enough to want to become a British citizen, which he did in 1851 (when the claim about living in the country 20 years was made, and when his home and office were at 1 Muscovy Court, Trinity Square, Tower Hill). His business partners by now included the wine and drink merchants Thomas Butcher and William Henry Howes, John Watson and the shipping agent George Lee: in January 1858 the partnership of Le Coq and Watson of Muscovy Court was dissolved. The size of deals Le Coq was doing can be gauged from the wreck of the motor sail ship Oliva in 1869 on its way from London to Danzig, when it ran into reefs off the coast of Norway during a storm and went down shortly afterwards with a cargo that included bottled beer from Barclay Perkins’s brewery being exported under the A Le Coq name worth £751 – perhaps £150,000 today.

Albert retired from the business in 1861, and returned to Berlin, where he died in 1875, and the firm of A Le Coq & Co was left in the hands of two more partners, John Turnbull and Richard Sillem. The Sillems were also originally German, from Hamburg, where they had been merchants since at least the 16th century, and where they must have known Albert’s father. Richard’s father Herman had come to England at the beginning of the 19th century. However, Richard Sillem died aged 37 in 1866, and his place in the partnership was evidently taken by his brother Oscar Hyde Sillem, born 1838. After Albert Le Coq’s death his son, Andreas August was no longer interested in the London beer exporting business, preferring, it appears, to run the seeds business he had set up in Darmstadt, Hesse, and in 1881 the London export operation was sold to Oscar Sillem, though still operating under the A Le Coq name. (Back in Germany the Le Coqs were raised to the aristocracy, becoming Von Le Coq: Albert’s great-grandson, August Robert Gerhard Albert von Le Coq, was an officer in the German army, and died, aged 20, in 1917, on the Western Front, ironically not far from where his ancestors had lived two centuries earlier.)

In Britain, meanwhile, business flourished, with Oscar Sillem never having to visit Russia himself: the beer was shipped out, and the Russian merchants who bought it would turn up unannounced at A Le Coq’s offices in Orange Street, Southwark to pay upfront with Tsarist gold rubles. The firm had agents across Russia and into Siberia, and was even selling its stout in China, while “from the mysterious country of Tibet, even, reports had come of the long, slender A Le Coq bottles being used as candlesticks.” Andreas August Le Coq was in China from 1852 to 1855, having sailed out round the Cape and arrived in Hong Kong late in 1851: his son Albert August von Le Coq became a famous archaeological and ethnographic explorer in Central Asia and China, taking part in four expeditions to Chinese Turkmenistan that brought back hundreds of crates of material to Berlin.)

However, in the early 1890s Le Coq’s trade in Russia began a rapid decline, and in 1895 Oscar sent his 28-year-old son Herbert Oscar Sillem to St Petersburg to investigate the reasons for the drop-off in orders. Herbert did not, at that time, speak Russian, but he had been educated in Switzerland and did speak German and French. The latter was of particular benefit in dealing with the business community in St Petersburg, since French was the preferred language for communication in Russian high society.

Herbert quickly found there were two big problems. The first was the high tariffs imposed on imported beers, coupled with the high freight charges put on foreign beers by the Russian railways, four or five times higher for imports than for Russian ones. These together pushed up the price of A Le Coq’s products on the Russian market, hampering sales compared to cheaper local brands. The second problem was the enormous amount of fake A Le Coq Imperial Extra Double Stout being sold, produced by “several” different brewers. Acting as his own detective, Herbert Sillem uncovered “huge” warehouses in St Petersburg filled with counterfeit A Le Coq beer. However, when he reported this to the police, nothing happened.

The Russian finance ministry told Herbert explicitly that no change would be made to the high import charges, and the Sillems eventually decided that to protect their market they would have to move their headquarters to St Petersburg and start bottling in Russia, particularly after the import tax went up another 50 per cent in 1900 to 72 kopeks, or 1s 6d, per quart bottle, having risen from 15 kopeks a quart bottle in 1881. A warehouse was thus rented in Italyanskaya in St Petersburg, in 1906, a short distance from the Nevsky Prospect, where a bottling plant was installed, while Herbert Sillem lived next door in the Hotel d’Europe. A Le Coq dropped its long-time supplier, Barclay Perkins, and the beer supplied for bottling in Russia came instead from another big London stout and porter brewer, Reid & Co, which had merged with two of its rivals in 1898 to form Watney Combe & Reid: Reid’s had made a strong “Russian stout”, with an OG of 1100, for many years.

The Sillems also began looking for a brewery inside Russia where they could brew their own Imperial Extra Double Stout (instead of having to import it from England), and thus be taxed as a local product rather than a foreign one. Some had doubts that stout could be brewed in Russia successfully. But Oswald Pearce Serocold, a director at Reid’s, promised “counsel and help” in getting a brewery in Russia to brew good stout.

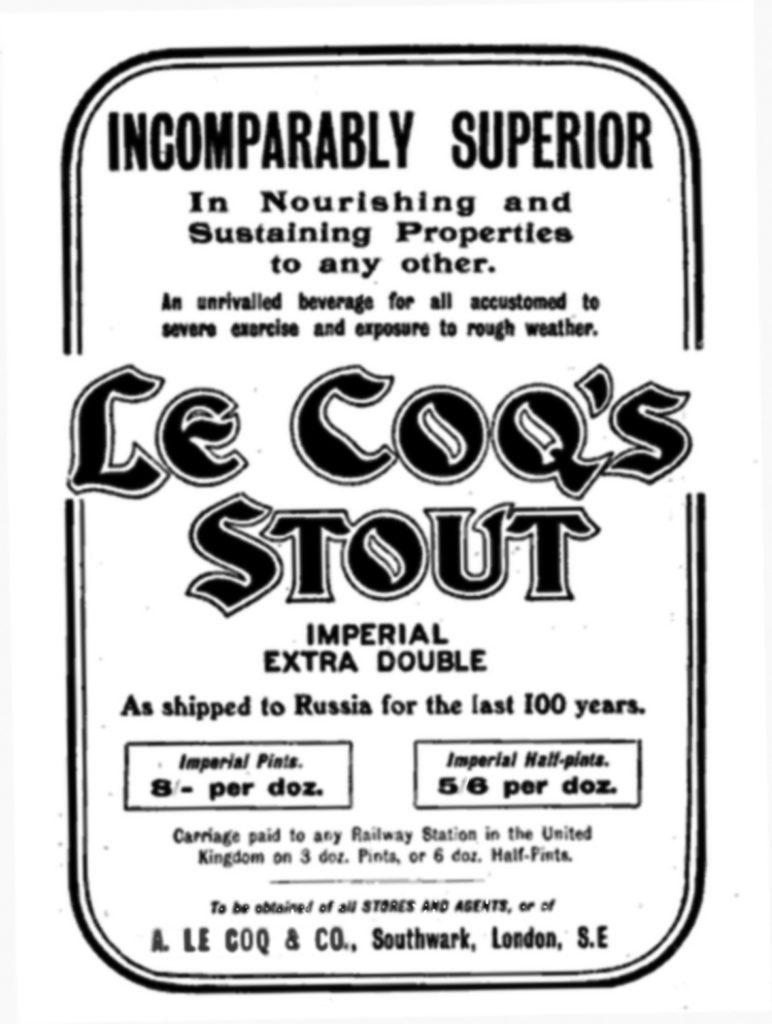

Before this happened, around 1903, A Le Coq began selling the Imperial Extra Double Stout in Britain, in pints and half-pints, advertising it in Country Life and Golf Illustrated as “Incomparably superior in nourishing and sustaining properties to any other … an unrivalled beverage for all accustomed to severe exercise and exposure to rough weather.” The Lancet magazine reviewed it, as it did other beers, finding the stout, “shipped hitherto exclusively to Russia”, had an abv of 11.61, “a rich malty flavour”, “a very considerable proportion of nutritives”, and was “free from excessive acidity”.

Eventually, in 1911, after a long search for a brewery in Russia, the A Le Coq directors picked the Tivoli lager brewery in Dorpat, Livonia, the town now known as Tartu, in modern-day Estonia. The operation had been started in 1827 by a man called Justus Reinhold Schramm, and a big new brewery had been built in 1894-96, with modern equipment, including a new drum maltings that was claimed to be only the second of its kind in the world. However, the owner since 1885, Julius Moritz Friedrich, had decided he wanted to sell up. Tests on water taken from boreholes at the brewery showed it was for “all practical purposes, identical with the water of the London Brewery which has hitherto supplied Messers A Le Coq and Co,” and it was acquired for £91,000.

In its prospectus to potential investors in the brewery in 1912, A Le Coq said the Tivoli operation would be able, once the brewery plant had been extended, to supply “a first-class Stout at a price within the reach of the general Russian public.” Oswald Serocold helped A Le Coq recruit an English brewer and a maltster to produce stout at the new plant in Dorpat. After problems were found with the plans for the new stout plant, which were designed in England, delaying the start of stout brewing for three months, the first sample batch arrived in April 1913. Unfortunately for British investors in A Le Coq, barely more than a year after the start of attempts to brew within the borders of the Russian empire, the First World War erupted, with Russia eventually banning alcohol as part of the war effort. Then came the Russian Revolution, which cut off the brewery, now in an independent Estonia, from its previous major market.

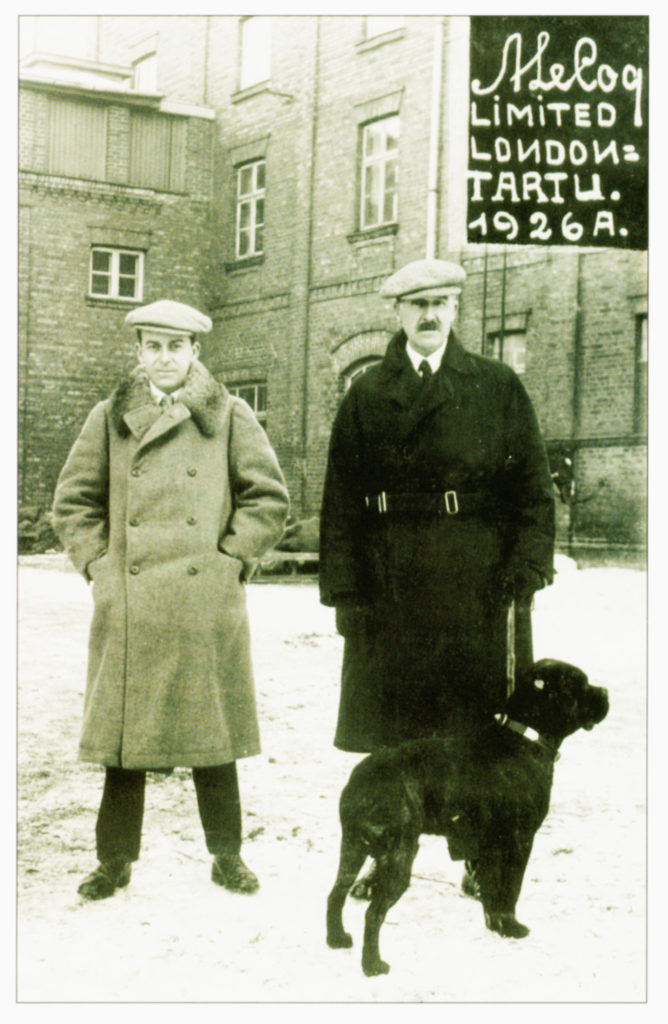

All the same, in 1921 the A Le Coq brewery reopened in what was now Tartu under the Sillems, making light and dark lager for the Estonian market, and in the 1920s it brewed approximately a third of all the beer brewed in Estonia. In 1926 it began production of imperial stout again. There was even an attempt, in 1929, to export imperial stout to Germany, with a couple of boxes of bottles being sent to Hamburg: the arrival of the Great Depression, however, put an end to that. By 1937 stout was just 0.4 per cent of the brewery’s total production, with 61 per cent being pilsen lager.

Then the Second World War came, and in 1940 the Soviet Red Army annexed Estonia, which was eventually incorporated into the USSR. The brewery, like every other industrial concern in the country, was nationalised, and its last director, Herbert Sillem’s son James Herbert, left Estonia: he and the other shareholders in A Le Coq were eventually compensated by the British government in 1969 for the appropriation of the brewery, from money made by selling the gold reserves of the former Republic of Estonia, which had been frozen in the Bank of England. During the Nazi occupation of Estonia the Tivoli brewery operated as the Bierbrauerei Dorpat, with around 80 per cent of production being consumed by the German army. After the Soviets swept back in the autumn of 1944, the brewery in Tartu eventually became one of the leading brewing concerns in the USSR, though it no longer made stout.

In 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed, and Estonia declared its independence. Although the brewery was still owned by the state, the name A Le Coq was brought back for some of its beer brands in 1992. In 1994 it brewed stout for the first time in decades, though critics described the beer as “a little too lager-like”. A year later the Tartu brewery was privatised, and in 1997 it was bought by Olvi Oy, the last remaining large independent brewery in Finland, which renamed its entire Estonian operation A Le Coq Ltd in 2003.

Meanwhile, the beer writer Michael Jackson had mentioned A Le Coq’s Imperial Extra Double Stout in his World Guide to Beer, published in 1977. By then about the only Imperial Stout still being brewed was the original Barclay Perkins one, now made by the company that had taken Barclays over in 1955, Courage, whose brewery stood alongside Tower Bridge. But in the 1990s an increasing number of American craft brewers were making Imperial Stouts, and in 1998 an American importer, evidently inspired by Jackson’s account of a genuinely Russian Russian Stout, decided to try to get an authentic version of the beer recreated. The Tartu brewery was happy to put the A Le Coq name to the beer, but it was agreed that it should be brewed in England, with the Estonians insisting that it be made by a small, independent brewery with experience of making porter-style beers. The company chosen was Harvey & Son of Lewes in Sussex. What those who picked Harvey’s could not have known was that Harvey’s head brewer, Miles Jenner, came from a family that had actually brewed imperial stout itself at its own brewery in Southwark in the 19th century, long before they moved to the seaside.

Jenner and his team set about trying to recreate a recipe for Imperial Extra Double Stout, leaning on the memories of brewers who had produced Barclay Perkins Russian Stout in the 1950s. The well water at Harvey’s was similar to that used by Barclay’s, with levels of calcium carbonate, calcium sulphate and sodium chloride that matched quite closely, and those same levels of minerals also fitted old descriptions of the best sort of liquor for brewing stouts with. The ingredients were 54 per cent Maris Otter pale malt, 33 per cent a mixture of amber, brown and black malts and 13 per cent invert sugar, to give an original gravity of 1106 and a final alcohol level of 9%. The historical hop rate was 15 pounds to the quarter, but Jenner and his team decided to lower that figure to 11 pounds to account for modern hops containing more alpha acid than they did in the past. Even so, the resultant 6lb per barrel was six times the hops that went into Harvey’s best bitter.

The first brew was made in 1999, and after nine months of conditioning it was bottled in corked bottles and released for sale in February 2000. Drinkers raved over its complex mixture of flavours. But something was still happening in the beer, Unknown to Harvey’s, a wild yeast called Debaromyces hanseni was lurking in the bottles, and after nine months it began making itself known, consuming the remaining “heavy” sugars and producing carbon dioxide, which started pushing the corks out. Luckily, the Debaromyces added even more complexity of flavour to the finished beer, as well as raising its level of alcohol, and Harvey’s have been happy to leave it to do its work, adding another three months to the time the beer is left in tanks to let it finish. The final conditioning by wild yeast is, in fact, the last touch of authenticity: there is no doubt that the original 19th century Russian stouts would have been part-fermented by wild yeasts such as Brettanomyces as well.

Today A Le Coq Imperial Extra Double Stout is brewed once a year, 27 barrels at a time, and is matured in either stainless steel or glass-lined mild steel tanks. Harvey’s also now bottles a what Miles Jenner calls a “nouveau” version of the beer, within six weeks of fermentation, and sold under the name Prince of Denmark. “Originally we produced it as a bit of fun for the Copenhagen Beer Festival,” Jenner says. “It was chilled, filtered and pasteurised but was surprisingly good and we kept it going as, invariably, people got tired of waiting for the new IEDS vintages while we ruminated as to whether they were ready or not! That said, it’s not bad and, among its many awards, won the Supreme Championship at the International Beer Challenge in 2012, having beaten IEDS to the Stout and Porter trophy. Such are the unexpected joys of brewing!”

An estonian and a russian craft brewery recently used the original recipe of the double stout brewed a hundred years ago…

https://www.ratebeer.com/beer/puhaste–af-brew-imperial-extra-double-stout/488015/

Anything the a.le coq factory makes nowadays is not even worth mentioning

In response to ME I would say that tastes are different and Estonian biggest brewery surely is making beer that “some” beer lovers like.

[…] https://zythophile.co.uk/2017/03/10/albert-le-coq-is-not-a-famous-belgian/ […]