Autumn, season of mists and mellow, fruity ales, as John Keats might have written, if he hadn’t been more of a blushful hippocrene, beaker of the warm South man. As the early evenings darken, and the leaves and the temperatures fall, it’s one of the joys of the season that we can start drinking strong, dark beers again, sitting by the fire in the snug – or by the fire in your own home, if you prefer. I often do. I have a place at one end of the sofa, close enough to the fire that I can toast my toes, with an old oak blanket box alongside that I rest my beerglass on, where I sit and read, or listen to music, while whatever the weather is doing outside can be ignored.

If you have been looking at national newspaper feature pages recently, you will not have been able to avoid articles discussing hygge, the Danish word meaning something allegedly untranslatable in between and greater than “cosy” and “comfortable” and “safe” that is the condition all Danes allegedly seek to attain. Of course, we actually have a perfect translation of hygge in English, or at least a word that describes the equivalent state of warmth and comfort and safety Britons desire: snug.

More than 230 years ago the poet William Cowper wrote: “There is hardly to be found upon the earth, I suppose, so snug a creature as an Englishman by his fire-side in the Winter.” He wasn’t wrong. And outside the home, some pubs provide us with a room where this blissful level of being can be achieved, a room generally only to be entered from inside the pub, with no street windows or doors, private and secure, almost always small enough that half-a-dozen will be a heaving crowd, and ideally with its own servery hatch to place orders at the bar. This room of happiness is actually named for the state of safe comfort, like the bug cuddled down deep in the protective tufts of his rug, that we seek between its enclosing walls: the snuggery or snug.

Far fewer snugs exist now than once: I mourn the snug at the Pelham Arms in Lewes, long torn down and thrown away as part of the marchto the future, which sat between the front and back bars: just room for one table and six chairs, its own section of the island bar, where serving staff could be easily and speedily hailed – it was as good as having your own private pub.

Far fewer snug beers still exist, too. One of the finest, Young’s Winter Warmer, remains with us, thanks be to Gambrinus, though no longer brewed in London. But still this morning the first casks of the 2016/17 season were tapped at the Thames-side White Cross in Richmond, the 25th year that the ceremony of the nouveau rechauffement d’hiver has been enacted, attracting 120 or so early drinkers happy to pay £12.50 for the traditional two-pints-and-a-full-English-breakfast. Winter Warmer, regular readers know, was called Young’s Burton until 1971. It’s a ruby-brown classic of the sort of ales that developed from those brewed in Burton upon Trent before that town became best known for heavily hopped pale ales and IPAs: well-rounded, mellow, old-oak dark, 1055 OG, but only five per cent ABV, and with a brown, fruity sugar tang (from the “YSM”, Young’s special, proprietorial mixture of brewing sugars that go into the copper along with the wort) offset by a hint of bitter undercurrent. It’s the beer equivalent of a thick scarf and warm woolly gloves, and yea, a couple of pints will leave you truly snug.

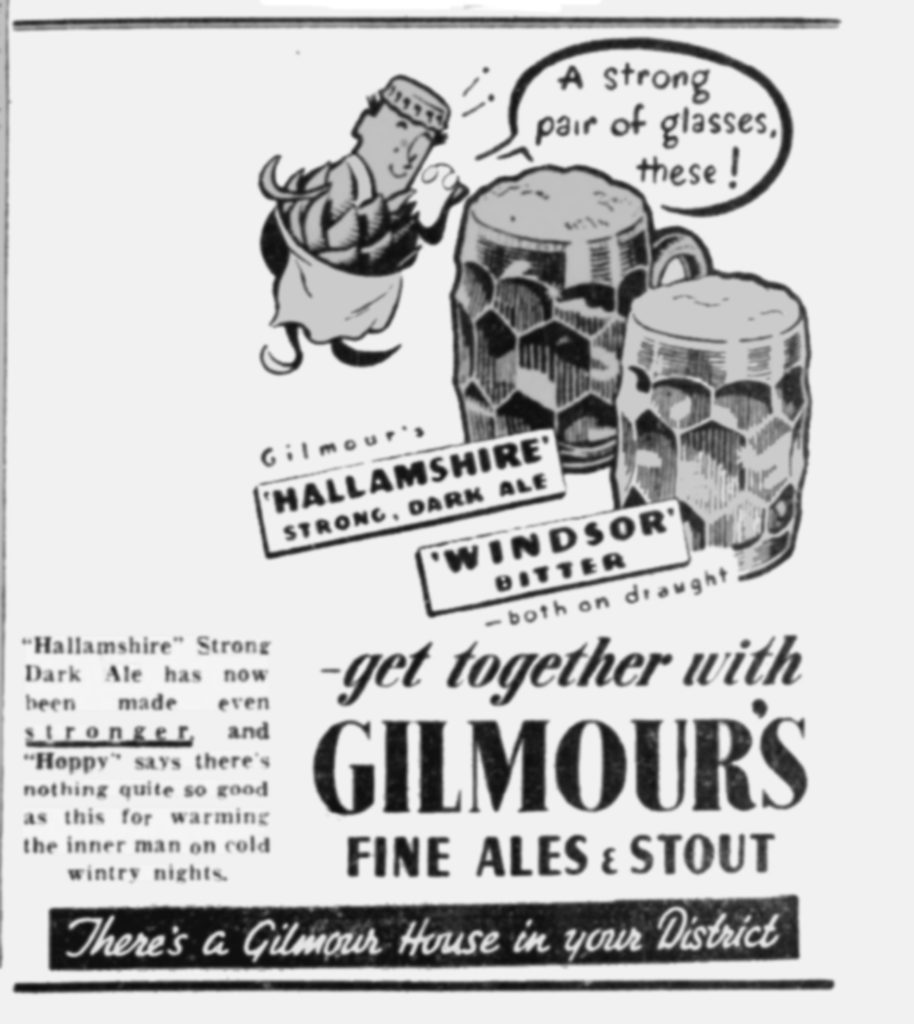

Once almost every London brewery made beers like this for winter consumption, and large numbers of other brewers around the country did so too, on draught and in bottle. This was a beer with its roots in the lightly hopped ales of the 18th century and earlier, where malt flavours and strength were the qualities brewers and drinkers sought, not hoppiness.

There are “snug” comfort foods to go with these beers, too: not just the FEB, or grilled lamb chops, or liver-and-bacon, but macaroni cheese (my top tip: don’t put too much cheese in the sauce, but make a first grilling with a good cheesy crust, then beat that crust into the macaroni-and-cheese mix and put another layer of cheese on top, grilling that in turn), or risotto, or dumplings and stew (SUCH an under-rated dish): all work well with dark ale as an accompaniment – and, indeed, ingredient, in the stew.

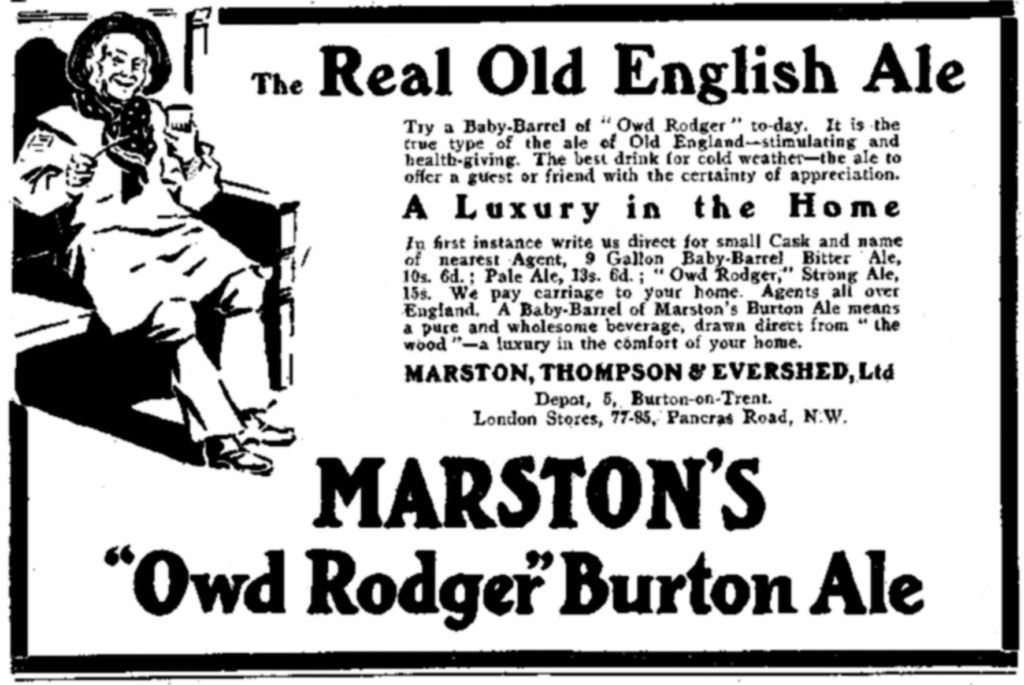

Alas, “mac ’n’ cheese” is strangely trendy today, but Burton old ale must be the least fashionable beer style on the planet. Strong dark ales haven’t been fashionable since the First World War, at least, being in the shadow of their weaker brethren, dark milds, although you can still find examples on sale from the 1920s to the 1950s, and from Sunderland to Portsmouth. Today Marston’s is still making Owd Rodger, another great fireside beer, after more than a century, about the last Burton Ale still regularly brewed in Burton, and the brewery is still using a drawing of the same besmocked old country bhoy to advertise the beer that it was in 1910.

Alas, “mac ’n’ cheese” is strangely trendy today, but Burton old ale must be the least fashionable beer style on the planet. Strong dark ales haven’t been fashionable since the First World War, at least, being in the shadow of their weaker brethren, dark milds, although you can still find examples on sale from the 1920s to the 1950s, and from Sunderland to Portsmouth. Today Marston’s is still making Owd Rodger, another great fireside beer, after more than a century, about the last Burton Ale still regularly brewed in Burton, and the brewery is still using a drawing of the same besmocked old country bhoy to advertise the beer that it was in 1910.

Other dark beer styles are available: Theakston’s Old Peculier, to me, doesn’t have the fruitiness that Winter Warmer and Owd Rodger have, and comes, I think, from a slightly different, rather drier tradition of dark strong ales. McEwan’s Champion, another beer I turn to with much anticipation when the trees start to turn to brown, is in Edinburgh’s line of fruity dark ales, very close to the Burton variety. Other “fireside beers”, by which I mean dark ales – so not stouts or porters, which are beers, or, rather, from the “beer” tradition – of between 5.5 per cent and 7.5 per cent abv, strongly malt forward, muted hop flavours, though with bitterness in the background, lacking the roast, chocolate and coffee flavours that stouts and porters have, with a balanced, often full and fruity sweetness, include Adnam’s Tally Ho (which has hints of liquorice, too), and Broadside, and Greene King’s Strong Suffolk, which is a blend of a beer called BPA, or Burton Pale Ale, a typically Burton-style sweet, darkish beer made with dark sugars and crystal malt, and aged 5X, a much stronger dark ale.

But you’ll spot that all these beers are decades and more old, and make by established brewers. Few “new” brewers make a dark ale. Burton ale effectively vanished in the 1960s, as did the snug bar soon afterwards. What we want is a Campaign for Real Snugness.

(A propos of things snug, here’s a tremendous video about snug bars in Dublin, which features the marvellous Ryan’s of Parkgate Street, one of my favourite bars in all These Islands.)

I have to give props to Chiltern 300s Old Ale, which I can’t get enough of right now! Wonderful Burton Ale that tastes stronger and richer than the 4.9%

What a great style to drink – I always look forward to it!

But on a possibly annoying pedantry-type note… would ‘old’ refer to an aged version and showing flavour notes associated with age?

Either way – great to highlight this wonderfully flavoursome style

“Old” certainly used to refer to an aged version with those flavour notes that came with maturity, and indeed it’s probably worth saying that may not be so true today …

Fullers 1845 is another great one. In fact I think Burton is my favourite style, rarely does anything else quite hit the spot as well.

[…] Martyn waxes lyrical about old ales and Burtons, singling out Young’s Winter Warmer, Marston’s Owd Roger, McEwan’s Champion and Theakston’s Old Peculier. I’ve long been a fan of these styles & others in the same neighbourhood (e.g. dark barley wines, dubbels & ‘quadrupel’s). I’m a particular fan of one that Martyn didn’t mention, Robinson’s Old Tom, which for several years now I’ve regarded as one of the best beers in the world. […]

Blind taste test with some surprising results – surprising to me, at least; I was expecting Owd Roger to finish a lot lower.