In a shiny 12-storey building in Bishopsgate, on the edge of the Square Mile, is a company that represents the last faint echo of a time when one family ran the two biggest breweries in the world.

The City of London Investment Trust is, today, a £1 billion business with investments in everything from pharmaceuticals to mining, and power supply to media, and a record of increasing its dividend every year for the past half-century. But the firm started in 1860 as the City of London Brewery Co, and its roots lie in the brewing industry as far back as the 15th century.

The City of London Investment Trust is, today, a £1 billion business with investments in everything from pharmaceuticals to mining, and power supply to media, and a record of increasing its dividend every year for the past half-century. But the firm started in 1860 as the City of London Brewery Co, and its roots lie in the brewing industry as far back as the 15th century.

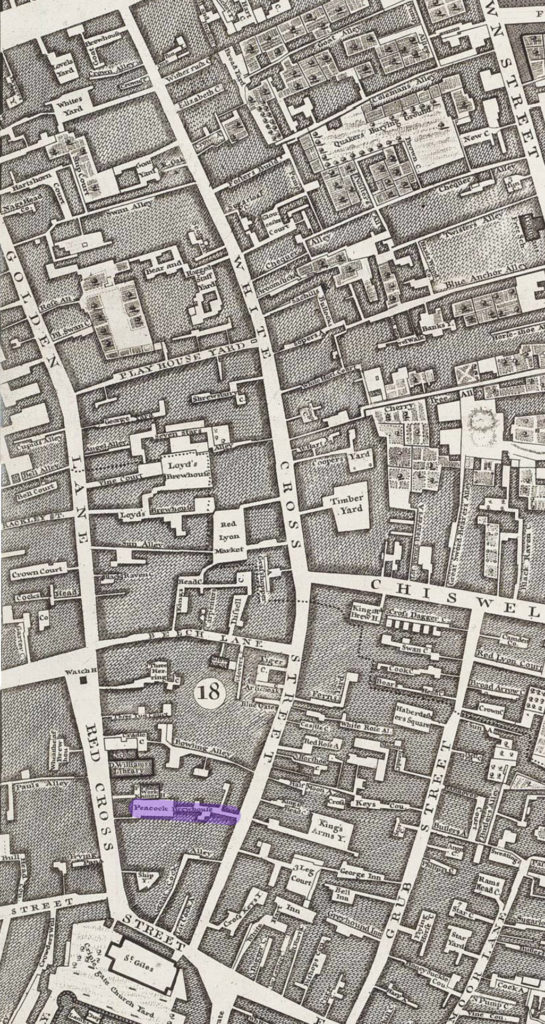

The family that dominated the early history of the concern were the Calverts, landowners from East Hertfordshire, who married into ownership of, first the Peacock brewhouse in Whitecross Street, by the Barbican, on the northern side of the City of London, and then the Hour Glass brewhouse, three quarters of a mile away off Thames Street, by the river. In the middle of the 18th century these were the two biggest porter breweries in London, and, therefore, the biggest breweries in the world.

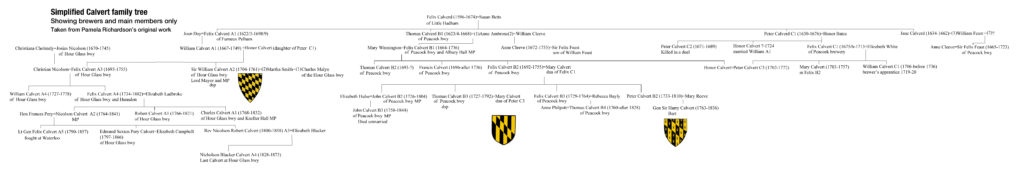

However, the Calverts today are much less well known than their rivals, such as Whitbread, Truman and Barclay Perkins, in part because the family name was taken off the business in the middle of the 19th century, partly because no physical trace remains of their brewing sites and partly because the firm they founded did not quit brewing so much as drift away from it. But one big reason for the Calverts’ current obscurity is the extreme difficulty involved in untangling the dense thicket that is their family tree, as the descendants of Felix, Thomas and Peter Calvert, the three sons of Felix Calverd (sic) the family’s 17th century patriarch, spread out and multiplied down the years.

The common habit of using the same first names down and across generations means that after the first Felix Calvert, or Calverd, was born in 1596 there were 12 Felix Calverts, seven William Calverts and seven Peter Calverts in the 17th to 19th centuries. Thanks to cousin marriage, one Felix Calvert, 1729-1764, a partner in the Peacock brewhouse, had a father also called Felix Calvert, and both his grandfathers were called Felix Calvert as well, while his great-grandfather’s great-nephew, Felix Calvert 1735-1802 (who also had a son called Felix Calvert), was a partner in the rival Hour Glass brewhouse.

The result is that there has not been a book or article mentioning the Calverts and their breweries that does not have major facts wrong. One book from 2011 has six errors in one six-line paragraph. Another recent publication called a high-profile member of the clan, Sir William Calvert, “the grandson of Thomas Calvert”, adding: “though there is some confusion in various books”. Indeed: Thomas was actually the one son of Felix Calverd that Sir William was not descended from. Cousin marriage meant his father (another William) was the son of Felix junior while his mother Honor was the daughter of Felix junior’s and Thomas’s brother Peter. The Museum of London Archaeology managed to invent a completely fictitious member of the family, “Henry”, and get the date the family acquired the Hour Glass brewhouse totally wrong.

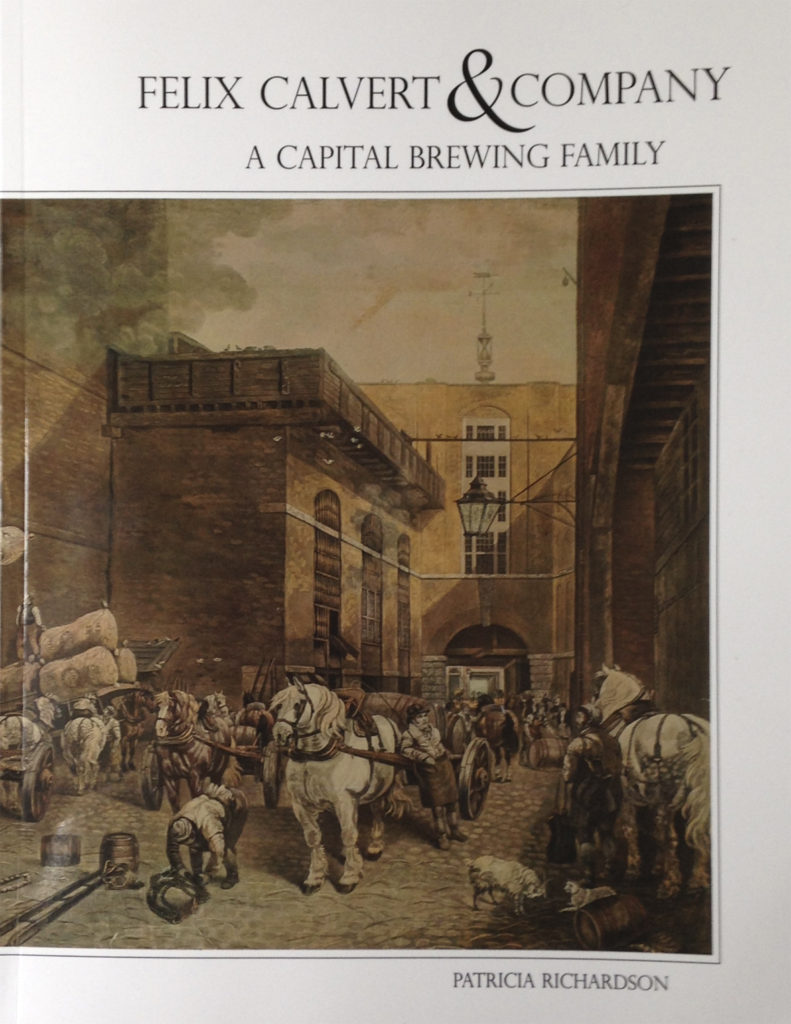

Hurrah and thrice hurrah, then, for Patricia Richardson – herself a tenth-generation descendant of Felix the patriarch – who has pulled apart all the different Calvert strands and published a book that is a readable, illuminating and fascinating telling of what could more than easily have been an extremely confusing story. She has solved the problem of tracing all those Felixes, Williams, Peters and the rest by labelling the families of Felix Calverd’s three sons A, B and C, and then numbering each new bearer of an old first name consecutively within the stream, so that, for example, Felix Calvert 1729-1764 of the Peacock brewery is Felix Calvert B3, his grandfathers are Felix Calvert B1 and C1 respectively, and his distant cousin at the Hour Glass brewery, Felix Calvert 1735-1802, is Felix Calvert A4.

Hurrah and thrice hurrah, then, for Patricia Richardson – herself a tenth-generation descendant of Felix the patriarch – who has pulled apart all the different Calvert strands and published a book that is a readable, illuminating and fascinating telling of what could more than easily have been an extremely confusing story. She has solved the problem of tracing all those Felixes, Williams, Peters and the rest by labelling the families of Felix Calverd’s three sons A, B and C, and then numbering each new bearer of an old first name consecutively within the stream, so that, for example, Felix Calvert 1729-1764 of the Peacock brewery is Felix Calvert B3, his grandfathers are Felix Calvert B1 and C1 respectively, and his distant cousin at the Hour Glass brewery, Felix Calvert 1735-1802, is Felix Calvert A4.

When the Irish genealogist John Burke quizzed the family in the 1830s he was told that Felix Calverd the patriarch’s father was “the Reverend Mr Calverd, minister of Andover”, and they were descended from the Calverds of Lancashire. It was certainly an ancient Lancashire name: Adam Calfherd was in trouble for cutting down trees in Cockerham, Lancashire in 1363. But as Patricia Richardson says, no Reverend Mr Calverd of Andover can be identified. In addition, when the Calverts later took up grants of arms, they used variations on the distinctive black and gold stripes of George Calvert of North Yorkshire, who had become the first Baron Baltimore in 1625 (and whose arms can be seen on the Maryland state flag).

Felix Calverd the patriarch worked as a tallow chandler, and as well as the family home in Much Hadham, East Hertfordshire, he also had a house in Tooley Street, Southwark. After the restoration of King Charles II in 1660, Felix’s three sons, Felix junior, Thomas and Peter (who seem to have decided to change the spelling of their surname to Calvert) all became tax farmers, that is, they bought the right from the king to collect taxes on his behalf, and all evidently became wealthy. But some time around 1657, Thomas Calverd/Calvert, born 1624, had married Anne Ambrose, the daughter of William Ambrose, senior partner in the Peacock brewhouse in Whitecross Street, in the parish of St Giles Without Cripplegate, and become involved in the brewing trade.

The Peacock brewhouse dated from at least 1550, when it was held by James Pullen. Thomas was only at the brewery for 11 more years after his marriage to Anne Ambrose, for he died suddenly in 1668, aged 46. His executors were his father-in-law, William Ambrose (who lived to be past 90, dying in 1698) and his brother Peter, who had been brought in as a partner in the brewhouse. Peter, too, died in his mid-40s, in 1676: the shares in the brewhouse owned by Thomas and Peter went to their respective second sons, both called Felix.

However, after Ambrose died, the position of lead partner at the Peacock brewery went to another member of the extended family, Felix Feast. Thomas, Peter and Felix Calvert had a sister, Jane, who had married William Feast of Little Hadham, and then died in 1662. William had then remarried, and Felix Feast was his son from this second marriage, born in 1665. Feast was also Felix Calvert B1’s brother-in-law, having married his half-sister Anne Cleere (William Ambrose’s grand-daughter – frequently, and mistakenly, called Anne Cleeve) in 1695. Under Feast the brewery thrived: he was called “a great Brewer in White Cross Street” in 1716, when he gave away 400 chaldron of coals – around 570 tons – to “such poor people that he found were great Sufferers, and were hindered from Working by the hard Frost.” The Peacock pub, the brewery tap in Whitecross Street, was called a “House of Humming Stingo” by Ned Ward in his London pub guide of circa 1718, the Vade Mecum for Malt Worm. In 1723 Feast was elected one of the two Sheriffs of London, and, as was usual with sheriffs, he was knighted by the King, in January 1724. However, he had only weeks to enjoy his new title: the next month, on February 22, he was “seized with the Dead Palsy”, dying two days later, aged 58.

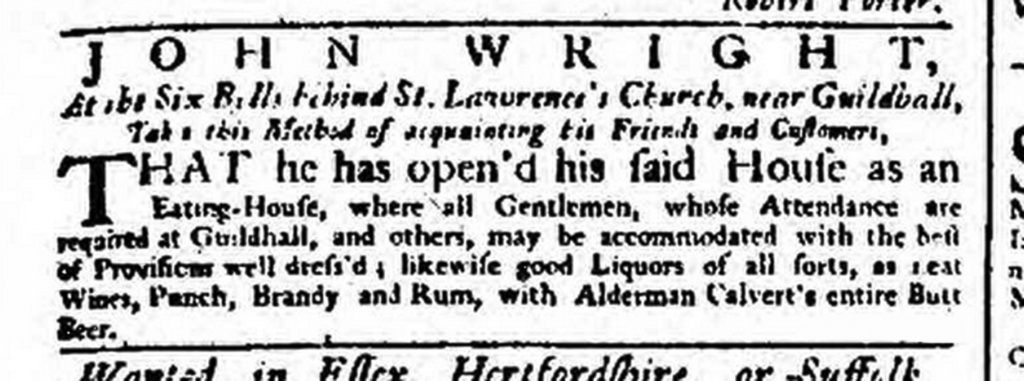

After Felix Feast senior died, the head of the Peacock partnership devolved to Thomas Calverd’s son Felix Calvert B1, who was also MP for Reading. Even in his late 60s he would ride from the brewery to his home in Berkshire, and in January 1733, aged 68, he was held up by a highwayman in Maidenhead Thicket and robbed of his gold watch and all the money he was carrying. He died at his London home alongside the brewery in Whitecross Street in 1736, and newspapers at the time described him as “a very great brewer … worth £80,000”, equivalent to more than £200 million today.

The Calverts continued as partners in the Peacock brewery, with cousins from the two junior lines having shares in the partnership. The Calverts also had on board one non-family partner, William Seward, who had been originally hired by Felix B4, and who appears to have become what today would be called the managing director. Although he only had a one-24th share of the partnership, the brewery was still known while he was in charge as Calvert & Seward, and under him the Peacock grew to be easily the biggest brewery in London, producing, in 1759/60, just under 75,000 barrels of beer, almost a fifth more than its nearest rival, Samuel Whitbread’s brewery in nearby Chiswell Street, on 63,400 barrels. Seward died in 1777, aged around 67, at his home in Colney Hatch.

Meanwhile the senior branch of the Calverts had gone into brewing themselves, around 60 years after Thomas Calverd, when Felix Calvert A3 of Furneux Pelham Hall in East Hertfordshire, great-grandson of Felix the patriarch, married Christian Nicolson, daughter of Josias Nicolson of the Hour Glass Brewery, Thames Street, in 1716, when he was 23 years old. Josias Nicolson was descended from a line of Southwark brewers going back at least as far as William Mayhew, who died in 1612. Josias seems to have become a partner in the Hour Glass brewhouse early in the 1690s, since he is described as a brewer “of All Hallows the Great”, the Hour Glass’s parish, when he married Christian (or Christiana) Cholmley in September 1693, aged about 26. Christian, incidentally, was the daughter of another big Southwark brewer, John Cholmley of St Olave’s, “the King’s brewer” (that is, a contract brewer for the army and navy) in 1681.

After the Hour Glass brewery was rebuilt in 1885, the fascia fronting the Thames carried the boast: “Established in 1580”. This was unnecessarily modest. In the records of the City of London an assignment dated February 1431 gives a list of brewing utensils in the custody of John Reynold, brewer, at the “Heywharf” in “Heywharflane”. Excavations between 2005 and 2007 on the site by Museum of London Archaeology found evidence for a series of keyhole-shaped stone hearths/furnaces, most likely used for heating water for dyeing or brewing, and dating from the 15th to 16th century. By 1552, in the reign of Edward VI, the brewery site looks to be occupied by Henry Campion, later beer brewer to Queen Elizabeth. Campion was certainly brewing there in 1563, since the London diarist Henry Machyn recorded that on 8 March that year “ther was a mad [maid] dwellyng in Hay lane with master Campyon berbruar in grett Allalowes in Temes strett dyd falle owt of a wyndow and brake her neke.”

In 1598, John Stow, writing in his Survey of London, suggested the brewhouse had originally been built by “one Pot”, which has led some historians to identify it as the premises of Henry Pott, a Thames-side brewer from at least 1534. But the evidence suggests Pott was brewing (until shortly before the end of 1550) in Grantham Lane, later Brewer’s Lane, five turnings further west along Thames Street from Haywharf Lane, in a “bierbrewhouse” run in the early 16th century by Sir Ralph Dodmore, brewer and, later, mercer, and Lord Mayor of London in 1529. According to Stow, Dodmore’s brewery was still running in 1598.

Haywharf Lane became known as Campion Lane, after Henry and his family. His son Abraham carried on brewing there, and was supplying the newly formed East India Company early in 1601with “beare” worth £646 15s for the four ships which set out for the Indies on the company’s first every trading voyage. (It looks as if he continued to supply the court of James VI and I, since in 1611 he was petitioning the Earl of Salisbury, the Lord High Treasurer, for a huge £7,277 12s 3d, “the surplus of his accounts due from the King and Prince for the past three years.” His nephew Richard still controlled the site in 1666, when the brewhouse was one of 16 breweries destroyed in the Great Fire of London. In 1668 Richard Campion struck a deal to lease the brewhouse grounds with John Hammond, though there was some dispute over whether Campion or Hammond should rebuilt the brewery buildings, which doers not appear to have been settled until 1669. By 1698 “Captain” Hammond was in a partnership at the brewery with Captain Henry Tate, and later William Tate was one of the partners in the Hour Glass concern with Josias Nicolson and Samuel Smith. Around 1719 “Nicholson and Tate” are mentioned by Ned Ward as suppliers to the Horse Shoe pub in Blowbladder Street (now part of Cheapside).

Josias’s middle daughter, named Christian after her mother, was born in 1695. She was a great catch: newspapers in 1716 reported that “Squire Calvert” of “Hattfordshire” was “marryed to Mr Nicholson’s Daughter, a great Brewer in Thames Street, with whom he is to have £10,000 Portion,” a sum equal to about £1.3 million today.

Exactly when Felix A3 entered into the Hour Glass brewery business as a partner is unclear, though he was named in an Old Bailey court case in February 1731 when a man called Barnaby Perry of Allhallows the Great parish was found guilty of stealing 50 pounds of lead “from the freehold of Messieurs Josiah Nicholson [sic] and Felix Calvert”. His youngest brother William A2, the later Lord Mayor and knight, married Martha, widow of Charles Malyn, brewer of Southwark, and daughter of Samuel Smith, one of Josias Nicolson’s, in 1732 and was reported at the time to have “lately entered into partnership with Mr Nicholson and Company, Brewers, in Thames-street”. (Richardson has William marrying Mary only in 1749, but the Universal Spectator and Weekly Journal reports his marriage to “Mrs Maylin, widow of — Maylin, late Water–Bailiff of this City” in its issue of June 10 1732.)

Richardson also writes that William initially joined his cousin Felix Calvert B2 at the Peacock brewery, and only “in later life, after his older brother’s death” (ie after 1755) moved to the Hour Glass brewery. However, this appears to be totally wrong. All the evidence, from the newspaper report of his joining the Nicolson partnership in 1732 onwards, puts him only at the Hour Glass throughout his career, and actually running it as senior partner after Josias Nicolson retired. On June 9 1744 the London Evening Post reported that “Yesterday morning, about one o’Clock, a Fire broke out in a Malt Warehouse in Coal-Harbour Lane, belonging to Sir William Calvert & Comp. Brewers, adjoining to the Brewhouse, which burned with great Fury above two hours, and consumed that with three others, in which were 4000 Quarters of Malt, besides a large Quantity of Hops &c, and very much damaged the Brewhouse, the Loss of which is computed at 15,000l.” “Coal-Harbour Lane” is Cole or Cold Harbour, the next lane east from Campion Lane, and the brewhouse involved was the Hour Glass. (The newspaper reported that the fire was put out “with the assistance of some engines”, and “The Prince of Wales was present at the Fire and gave great Encouragement to the Firemen and others to do their Duty.”)

William had an active political career: he was an Alderman from 1741, MP for the City of London from 1742 to 1754 and for the notorious “rotten borough” of Old Sarum from 1754 to 1760 (one of six Calvert MPs), knighted in 1743, when he was one of the Sheriffs, and Lord Mayor of London in 1748. He seems to have been meant originally for a career in the church – he went to Emmanuel College, Cambridge, becoming a Fellow of the college in 1728 – but diverted instead into brewing. When he became Lord Mayor, a mocking ballad parodied him as “Sir Billy Tinsel”, and suggested that it was the “hundreds a year” possessed by the “buxom brisk widow” Mrs Malyn that had lured him from his ambition to be a bishop one day.

In 1748, the year of his mayorality, Sir William at the Hour Glass brewhouse and his second cousin Felix Calvert B2 at the Peacock, around three quarters of a mile away to the north. were the two biggest brewers in London, at around 53,000 to 55,000 barrels a year each. Of the other major porter brewers, Ralph Thrale at the Anchor brewhouse, Southwark, across the river from the Hour Glass, was making under 36,000 barrels a year, Benjamin Truman in Brick Lane just under 40,000 barrels and Lady Parsons at the Red Lion brewhouse in St Katharine’s (widow of Alderman Humphrey Parsons), 39,000 barrels, while Samuel Whitbread was brewing, but still two years from buying the site in Chiswell Street where he made his fame and fortune.

Sir William carried on running the Hour Glass brewery until his death in 1761, aged 57, while at the Peacock William Seward was joined by Felix Calvert B2’s sons John B2, Felix B3 and Thomas B3. By 1759/60 the Peacock had pulled well ahead of all its London rivals, with Calvert & Seward producing 74,734 barrels in 12 months, Samuel Whitbread 63,408, Benjamin Truman 60,140, Hope & Co of the White Lion brewery, Spitalfields, 55,306 barrels, and Sir William Calvert at the Hour Glass fifth with 52,785.

On Sir William’s death, control of the Hour Glass concern went to William Calvert A4, the third son of Sir William’s brother Felix A3, and Felix Calvert A4, the fourth son, since the oldest surviving son, Nicolson, was heavily involved in politics. It looks as if the Hour Glass had a rebuilding in 1772, since Alfred Barnard noted that year’s date on “several” of the brewery’s walls when he visited in 1890. By now Calvert’s porter was being drunk all over the country, and across the Atlantic: in 1775, the Hour Glass brewery and its rival across the river, Henry Thrale’s Anchor brewery in Southwark, each won government contracts to supply British troops in Boston with 5,000 butts of porter. William A4 died in 1778, after which the concern was called Felix Calvert & Co.

At the Peacock brewery, when William Seward died in 1777 he left his 30-year-old son, also William, £15,000, about £1.7 million today. William Seward junior, unsurprisingly, never worked: he became famous as an intellectual dilettante and anecdotalist, and friend of Dr Samuel Johnson and his circle. The Peacock continued with John Calvert B2 as senior partner, and by 1786 production was up more than 30 per cent on 1760 to 94,000 barrels of strong beer a year. But it had slipped from its position as London’s number one, while the Hour Glass was the third largest in town, having more than doubled output to 118,000 barrels, though still behind Samuel Whitbread on 130,000 barrels and William Truman Read at the Black Eagle brewery in Brick Lane on 121,000 barrels.

Over the next decade and a half, the two Calvert concerns each began to fall further behind their rivals, so that by 1800 the Hour Glass had fallen to sixth largest in the capital, on just over 74,000 barrels a year, and the Peacock was down to eighth place, on 45,500 barrels. In 1802 Felix A4, then aged 67, killed himself, putting a pistol to his head in a private room at a coffee house, Don Saltero’s, in Chelsea after dining on two mutton chops and a pint of wine. Newspaper reports at the time described Felix as “the celebrated opulent brewer”. The Hour Glass brewery carried on under his two middle sons, Robert and Charles, though it kept the name of Felix Calvert & Co.

By 1808 the Hour Glass was in eighth place among London’s big brewers, with output having dropped to a little under 69,000 barrels a year, despite the takeover in 1806 of a smaller porter brewhouse, Thomas Stanley and John Cass’s Star brewery in New Crane, Wapping, and the removal of all its plant to Thames Street. (This may have been prompted by a major fire Richardson says took place at the Hour Glass brewery in 1805: unfortunately the fire seems to have been missed by all the newspapers of the period.) The Peacock, meanwhile, was down to 12th place, on 32,000 barrels, just a third of what it had been brewing at its peak. (The table on p551 of Peter Mathias’s Brewing Industry in England, incidentally, appears to have reversed the production figures for the two Calvert breweries, certainly from at least 1786 onwards, leading Richardson to believe, understandably, that the Peacock was the larger of the two: newspaper accounts from the late 18th and early 19th centuries give the correct picture.)

The Calverts’ answer was to merge the two breweries, with the Peacock brewhouse shutting some time soon after July 1809 (it was demolished soon after and a debtors’ prison built on the site) and production moving to the Hour Glass brewery Output at the Hour Glass brewery soared as a result, to almost 133,500 barrels in the 12 months to July 1810, putting it fourth on the porter brewers’ league table (though still far behind Barclay Perkins on almost 236,00 barrels and Meux Reid on 214,600). However, production slipped back to 108,000 barrels a year in 1812, and 100,000 in 1814, placing it sixth, and Calvert’s continued to hover around sixth and seventh place in London’s brewers’ league table for the next 50 years.

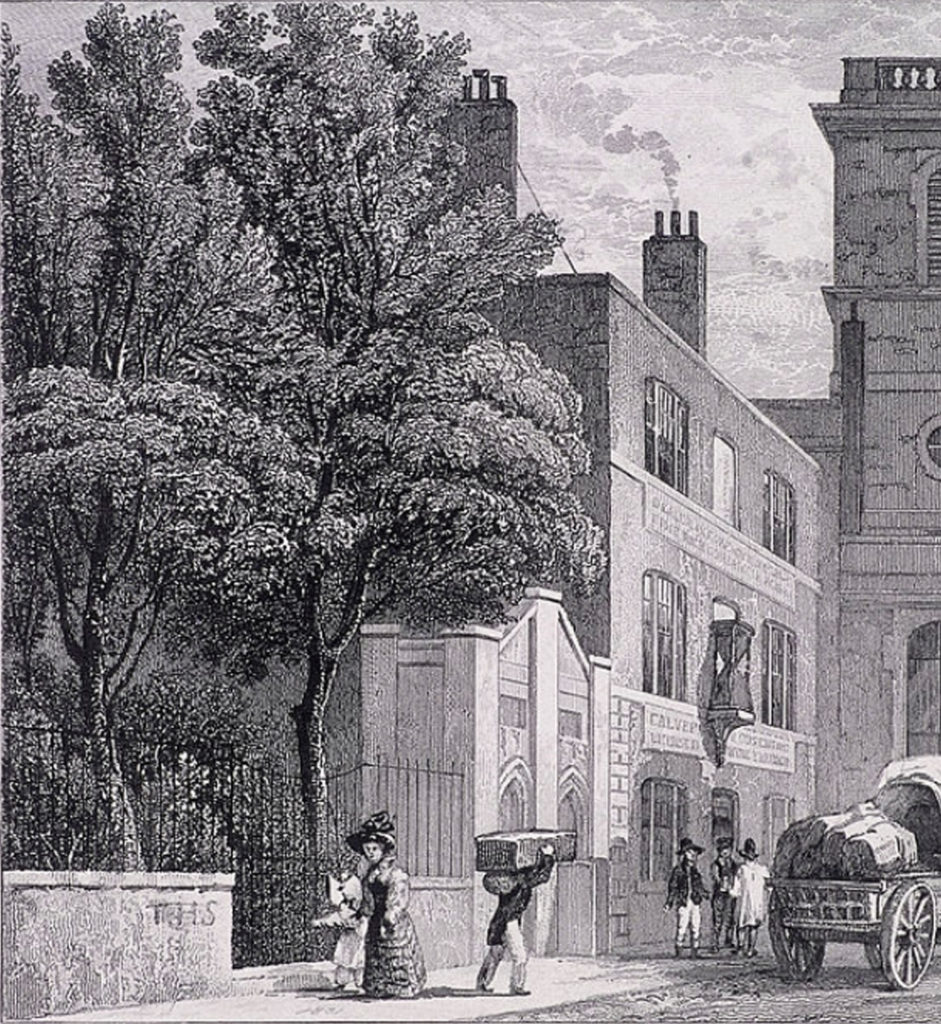

By the late 1850s be brewery was in a mess, financially, in 1858, the partners filed for bankruptcy, and in 1860 a new concern, the City of London Brewery Company, was incorporated to take over the Hour Glass brewery, the first big London brewing concern to become a limited company. The Calverts continued to own shares in the operation, and Nicolson Blacker Calvert, Robert’s and Charles’s great-nephew, was company secretary until his death in 1873 aged 45, the last Calvert to be actively involved in the brewing business (his first name reflected his descent from the Nicolsons, brewers of Southwark in early Stuart times). The Brewers’ Guardian recorded that when Nicolson Calvert’s coffin left the brewery (where, presumably, he had been living in the house on the site) on its way to Furneux Pelham in Hertfordshire to be buried in the family vault, “The whole of the staff of the counting-house, and all the men who could possibly be spared from their duties. spontaneously followed the hearse, and as the procession moved through a dense crowd of spectators in Thames-street, much feeling was displayed.”

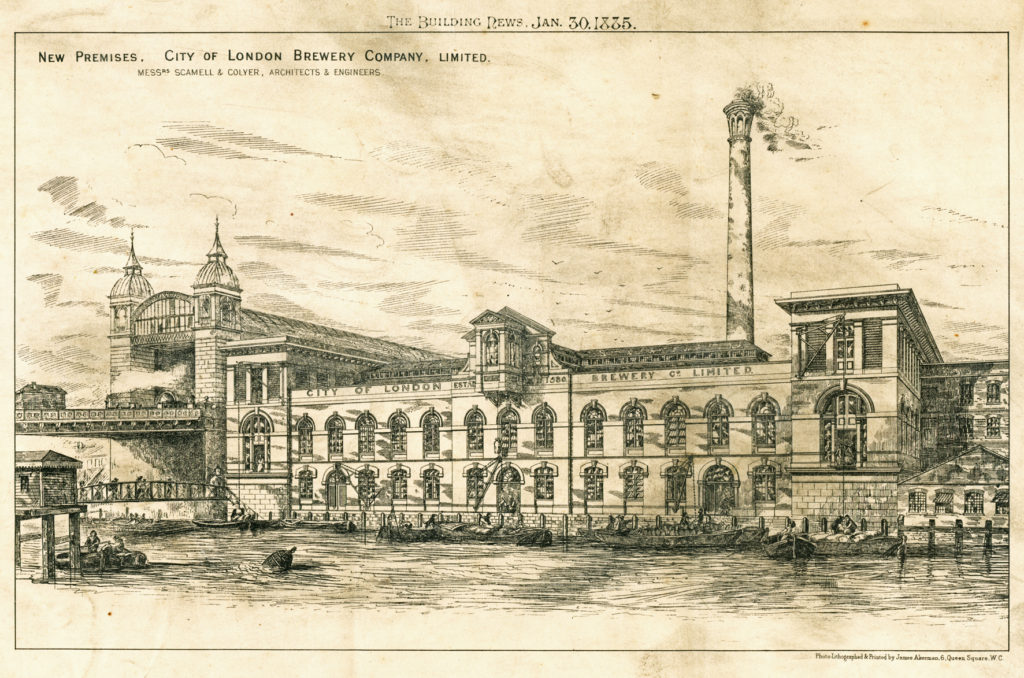

The company was thriving enough to pay for a rebuilding of the brewery in 1883, designed by the London brewery architects Scamell & Collyer (who designed a new brewery of John Smith’s of Tadcaster the same year). Production was now in two separate brewhouses, the West or old brewery, where the ales were brewed, and the new East Brewery, where production of the porters and stouts had been transferred. By now output had risen to an estimated 200,000 barrels a year,), but the company’s ranking had fallen to 10th. Another fiscal wobble in 1891 saw the firm reconstituted as the New City of London Brewery, though the “New” was dropped from the name four years later. In 1894, the church next door to the brewery site, All Hallows the Great, which had already lost its tower in 1876 to allow Thames Street to be widened, was pulled down completely, and the site sold to the City of London Brewery for £13,100, which built a new counting house on the spot.

Dividends had gone into decline from 1899, and by 1909-10 the company had stopped paying dividends completely. One of the problems, shareholders were told in 1905, was that in the “trade boom” of the 1890s, when brewers were snatching up as many pubs as they could before their rivals could get them, the CoLB “invested in a large number of public houses in the East End, and for a time the investment proved satisfactory. By degrees, however, the character of the East End population changed. It now consists very largely of the foreign element, and these foreigners, whatever else they may drink, do not drink beer. The consequence is that many of the company’s tied houses, which used to be very profitable, are much less so today.” The Daily Mail reported this as: “Unrestricted alien immigration into the East End was mentioned at the City of London Brewery Company’s meeting yesterday as one of the causes affecting their interests.”

Hoare & Co of the Red Lion brewery at St Katharine’s, to the east of the Tower of London, another former big porter brewery, was also struggling, and in 1911 a merger was suggested between the two firms. However, the City of London’s debenture stock holders failed to vote by a sufficient majority for the deal. A similar scheme was proposed the following year. Once again, however, a group of debenture stock holders refused to vote in favour, and the second scheme fell through.

A large brewery in the heart of the City of London was now a complete anachronism, and in 1914 the City of London Brewery agreed with Stansfeld & Co of the Swan Brewery, Walham Green, Fulham to lease the Swan Brewery for £3,000 a year, with the intention of transferring its production to Fulham. Unfortunately the outbreak of the First World War halted those plans, and brewing continued at the Hour Glass brewery. The revival of the move from Thames Street was not announced until 1921, being completed in 1922, with the two-acre Hour Glass site left “entirely empty”, and brewing carried on at Fulham “under the most modern conditions”.

Two years earlier, in 1919 the City of London Brewery had acquired a controlling interest in Nalder & Collyer’s Brewery Co in Croydon. The Croydon brewery continued brewing, and supplying its pubs. In 1926, meanwhile, the CoLB began a slow journey to extract itself from direct involvement in the brewery business. That year most of its own pubs were sold to Hoare’s for £1.4m and 200,000 £1 shares. The Swan brewery in Fulham and another 50 pubs were put up for sale in 1928, but failed to find a buyer. Eventually the Romford brewer Ind Coope bought 25 of the pubs, while the brewery was closed and converted into a soft drinks factory.

In 1931 the City of London Brewery Co officially changed its name to the City of London Brewery Investment Trust. The company secretary was Henry Groom, who had joined the firm in 1876, and retired in 1933 after 38 years in the same job. In April 1936 a deal was struck selling around 170 Nalder & Collyer’s pubs, mostly in Surrey, Sussex and Kent, to what was now Ind Coope & Allsopp, for a little over £2.2m, much of it in Ind Coope shares. CoLB kept the Croydon brewery, though not for very long, apparently, and a number of pubs, still run under the Nalder & Collyer name. By 1939 the City of London Brewery and Investment Trust was boasting that after Hoare’s brewery had been acquired by its East London rival Charrington’s, the CoLB was “among the largest shareholders” in both Charrington’s and Ind Coope & Allsopp.

The Hour Glass site, long used as warehousing, was hit and set on fire by German bombing in 1940 and again in May 1941, which left the brewery, and the former brewery tap, the Hour Glass pub at 89 Upper Thames Street, in ruins. The wrecked buildings were demolished in 1942: the hour glass that had been on the weather-vane at the top of the brewery clock tower was acquired by Adams’ brewery in Halstead, Essex. In October 1952 the Nalder & Collyer subsidiary put 22 licensed premises up for sale, all “country properties … being offered for sale because they are outside the range of the company’s normal activities.” It was hoped they would fetch £200,000.The trust’s last pub holdings were apparently sold in 1968.

In 1970 the City of London Brewery Investment Trust became part of the investment firm Touche Remnant. The brewery takeovers of the 1960s meant that its original holdings in Ind Coope were, by 1972, a £3.1m stake in Allied Breweries, while the holding in Hoare’s had become a £1.7m slice of another giant national brewer, Bass Charrington. It also owned shares in Scottish & Newcastle and Whitbread worth almost £1m. However, these were only a fraction of a total investment portfolio worth almost £39m, getting on for £1 billion today. The name itself had become an anachronism, and in 1981 it was changed to “City of London Investment Trust plc”. It is now run as part of Henderson Global Investors, which acquired Touche Remnant in 1992.

Felix Calvert & Company: A Capital Brewing Company

By Patricia Richardson

West Malling: Patricia Richardson

2015 pp232, £15

ISBN 978 0 957 4465 19

Fascinating stuff (although I may have skipped a Calvert or two). My micro-pub is definitely going to be called “The House of Humming Stingo”.

Interesting that beer was ‘humming’ in 1718; ‘humming ale’ features in some of the older folk songs. I’ve always wondered what it meant, and – checking the OED – it turns out that nobody knows, which is interesting if frustrating. The OED does record uses of ‘hum’ as a noun, meaning some kind of strong drink, from rather earlier than the first use of ‘humming’ in this sense, so it may be a back-formation – although that doesn’t help very much, because nobody knows where this ‘hum’ came from!

Re factual mistakes: the book cover shown says Patricia Richardson while the text refers to Pamela.

La la, don’t know what you mean, looks fine to me (hastily corrects egregious error …)

Thank you!

Hello Martyn,

I think there is a longstanding misreading of the name Cleeve in the records for this family. I read it as Cleere and this makes a very interesting connection with the carpenter architects, William and Richard Cleere and from my research, with Richard Cooper senior (1701-64), an important figure in the Scottish Enlightenment. You can read more about him here, where I’m sure you will come up with more questions, which I am happy to try and answer.

https://sites.google.com/site/richardcooperengraver/

Thank you, I’d certainly be delighted to hear more about yur findings.

Hello again,

I realised there was a repeated error while looking for the London ancestors of Richard Cooper, the Edinburgh engraver. To be fair they are not all misreadings of r and v, which is very easy to do, some are variant spellings (Cleare, Cleere, Clare). But by using wills and birth records it became obvious that William Cooper (1639-89) stationer, was married to Mary Cleere (1669) and not Cleeve as stated in the DNB. I wrote to the editor, provided the evidence and they changed the entry. His testament is witnessed by John Clarke sen. also a stationer and Richard Cooper’s master. Wills for the brothers Richard Cleere, (d. 1681) and William ‘Clare’ (d. 1682) famous as wood carvers and architects soon provided links to Mary Cleere, William Cooper’s wife. There is a very good article on the brothers here, in which the author makes a guess about some surnames but does get the first names right (https://georgiangroup.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/GGJ_2010_02_Smith.pdf

Sir Felix Feast was appointed Richard Cooper’s guardian by his mother, Elizabeth in 1709, her husband William, a bricklayer, having died unexpectedly in 1705. I discovered that Dame Anna Feast was pursued in Chancery ( 2 very long and tedious documents which I have transcribed!) by Richard’s maternal family in 1727 for payment of monies owed to him and his sister Elizabeth, by Anna Feast. I agree with you that Anna or Ann was the daughter of William Cleere, in fact the joiner above (second husband of your Anne Ambrose, wife of John Calverd B1).

I am still trying to work through these discoveries and make firm links to William Cooper the bricklayer, possibly a son of the stationer at the top of this comment. His apparently very early and unexpected death makes things a bit difficult.

Thank you very much, especially for all the hard work that clear;y went into unravelling all that – now corrected in the piece.

I notice that Patricia Richardson gives a birth date for Anna Feast. I have not been able to find that – does her book provide more genealogical detail on the Feast family?

Just a postscript: Richard Cooper senior sold a book ‘to teach distilling’ to a Scottish client in 1724, when he was just out of his apprenticeship and still in London. The proceedings in Chancery revealed that his father William, the bricklayer was still owed £1100 in a mortgage on the Spread Eagle Inn in Grace Church Street, which makes me wonder if he had built or rebuilt it before his death in 1705, possibly in partnership with his brother in law, the carpenter Henry Sell. [National Archives, C 11/772/52 Nicholls v Feast] – His sister Elizabeth was married to Francis Nicholls, a London mealman.

I am researching a Margaret Calvert (t), baptised Furneux Pelham 1651, who allegedly married a William Wright (no detail of this).

On Margaret’s baptism entry it says father was John.

Does the book give details of the wider family, or just those involved in the brewery?

Paul

Yes, Margaret is mentioned on pX of the book – she was the grand-daughter of the “first” Felix Calvert/Calverd and daughter of his son Felix Calverd 1623-1689

I thought that must be the case.

I came across a baptismal entry on F dMyPast and it said father was John. But that did not correlate with anything

Do you know If the book is still available to buy?

I’m afraid I have no idea if the book is still available or not. Try Amazon, or ABEbooks.