It’s a huge thrill to uncover facts that totally rewrite history. You’ll read in a great many places – here, for example, in a book published in 2014 – that the first porter brewed in America was made by Robert Hare, son of a London porter brewer, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1775. So when in 2017 I found an advertisement in an 18th century newspaper that showed porter being brewed in the American colonies ten years earlier than that, by someone else, in an entirely different state, it was shirt-over-the-head, run-round-the-room time.

Except that I found this story while researching for a chapter I was writing on the global spread of porter for the latest in the “Geography of Beer” series, published by Springer. I really wanted to keep the story I had found as an exclusive for the book, so I decided I couldn’t publish anything until the book came out. Ne’er mind, I thought, ’twill only mean a wait until early next year. Except that for a number of unfortunate reasons, publication of the book was delayed. And delayed. And delayed a bit more, leaving me sweating in case someone else stumbled over these same facts, and published the true story of America’s first porter brewer before I did. I had done some more digging, and found that the whole tale had appeared in a book written in 1968 about the now long-vanished estate where the first American commercial porter brewery was based: the author of that book, however, had failed to realise the significance of the story in the history of brewing, being more interested in the archaeology of the site and what it said about social conditions of the time. [Add: An article in Brewery History, the journal of the Brewery History Society, in 2016, which I had forgotten about until reminded, mentioned the brewery concerned, and the fact that it made porter, but failed to point out that this was the earliest known brewing of the beer in America.]

So: The Geography of Beer: Culture and Economics (Nancy Hoalst-Pullen and Mark W. Patterson, eds) was finally published this month, and it being out and in the public domain, I can now tell you the full, short and ultimately rather sad and tragic story of America’s First Porter Brewery. Sit back, pour yourself something dark, and away we’ll go.

Britain’s American colonies in the mid-18th century provided a market for more than just the tea that was to cause problems in Boston in 1773. In 1766 the sums remitted to England for London porter by the merchants of New York, Boston, Philadelphia and elsewhere were described as “very considerable”.

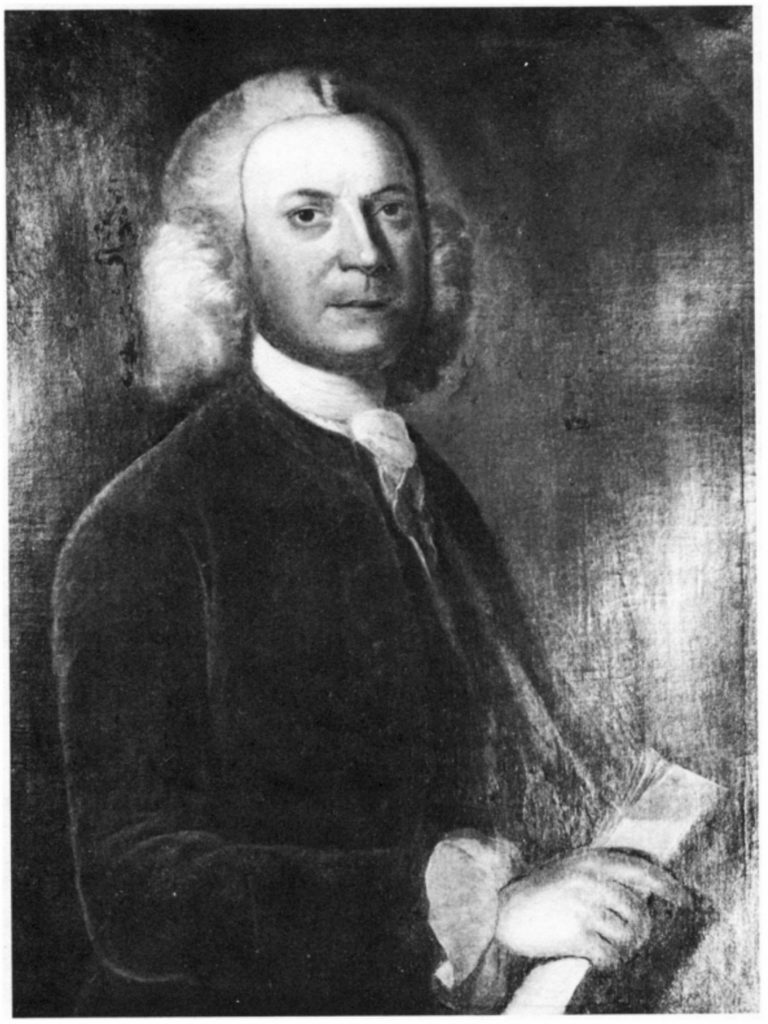

Growing imports of porter, and American colonists’ growing estrangement from Britain, eventually encouraged a Dublin-born American entrepreneur, lawyer and plantation owner, John Mercer, of Marlborough, Stafford County, Northern Virginia, to start brewing porter commercially, the first known porter brewery outside the British Isles. Mercer, the son of a Dublin merchant also named John, whose grandfather came from Chester in England, was born in February 1704 and came to America in 1720, aged 16. He had moved to Marlborough in 1726, initially leasing property in what was then a run-down settlement, and eventually built up a thriving tobacco plantation. He also began a career in the law and rose to be one of the top attorneys in Virginia, acting for George Washington among others, and a wealthy man. Late in the 1740s he poured money into turning his home in Marlborough into a Palladian manor house, filled with mirrors, marble-topped sideboards and furniture brought across the Atlantic from Europe.

As he entered his 60s, increasing illness, and deafness, forced Mercer to quit the law. He was also struggling with debts, and, looking around for a way to make money, decided “with self-deceptive optimism,” as one historian wrote, to start a brewery at Marlborough, reasoning that it could not fail to be profitable, because “our Ordinaries [inns and taverns] abound & daily increase, for drinking will continue longer than anything but eating.” He assured his son George that the venture “would quickly retrieve all my losses and misfortunes.” A brewery would, in any event, enable him to “brew for the family use, that they may have drink with their victuals” – the “family” here including Mercer’s black slaves, the Marlborough estate being home to “about 26 white people & 122 negroes.”

Mercer constructed a brewhouse and a malthouse, each 100 feet long and made of brick and stone, plus “Cellars, Cooper’s house [the brewery employed two coopers at £20 a year] & all the buildings, copper & utensils whatever, used about the brewery.” The purchases to equip the brewery included 50 yards of haircloth, a yard wide, for the malt kiln. Marlborough already had a windmill which could be used to grind the malt, but for the days when the wind did not blow, “I have now a hand-mill fixed in my brewhouse loft that will grind 50 bushels of malt (my coppers complement) every morning they brew.”

Mercer also laid out money on purchasing “about 40” black slaves, “to enable me to make Grain sufficient to carry on my brewery with my own hands,” and also began growing his own hops. He hired a man named Andrew Wales, or Wayles, “a young Scotch brewer,” who “affirmed that he had some years the charge of a brewhouse at Edinburgh,” and persuaded Mercer to spend £100 to alter the new malthouse. Another brewer, William King, arrived in September 1765, who condemned Wales’s alterations to the malthouse. King died the following month, but a short time later William Bailey arrived at Marlborough unannounced, sent by King’s nephew, a man named Wadman, and carrying with him a high recommendation as a brewer from his previous employer, Colonel John Tayloe, one of the richest plantation owners in Virginia. Tayloe said that Bailey’s brews had been “preferred by some gent. of distinction & good taste to very good Burton & other English ales.” Mercer wrote: “You may readily believe I did not hesitate to employ Bailey on such a recommendation, more especially as he agreed with King in blaming the alteration of the malt house & besides found great fault with Wales’s malting.”

Unsure which of the two, Bailey or Wales, was the better brewer, Mercer let both men brew separately. However, he wrote, “though Bailey found as much fault with Wales’s brewing as he did with his malting, that brewed by Wales was the only beer I had that Season fit to drink.” Bailey made enough beer to send a schooner-load of it to Norfolk, Virginia, but it was of such “bad character” that only two casks were sold. The rest had to be stored for two months, then returned to Marlborough. An attempt to distil it into whiskey was made, but with no success. Wales, although he had brewed drinkable beer, had only made around 550 gallons, the return on which was hardly enough to pay his £40 wages, let alone the maintenance for himself and his wife.

In 1766 the brewery made 550 bushels of malt, but the quality of much of the beer and ale produced was poor. Mercer wrote to his eldest son George that “Wales complains of my Overseer & says that he is obliged to wait for barley, coals & other things that are wanted which, if timely supplied with he could with six men & a boy manufacture 250 bushels a week which would clear £200 … My Overseer is a very good one & I believe as a planter equal to any in Virginia but you are sensible few planters are good farmers and barley is a farmer’s article.”

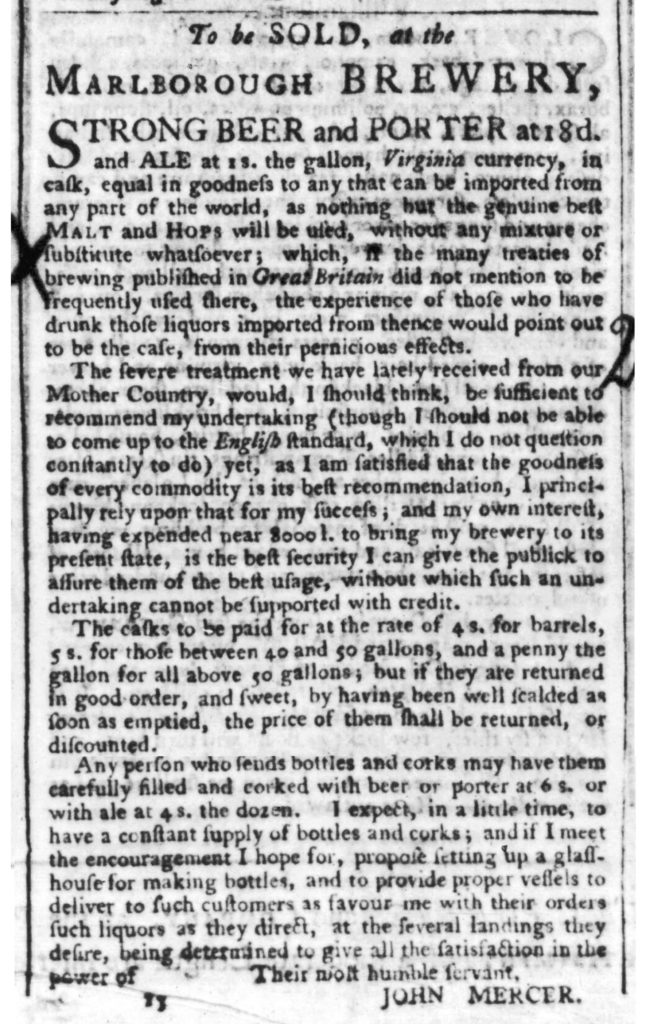

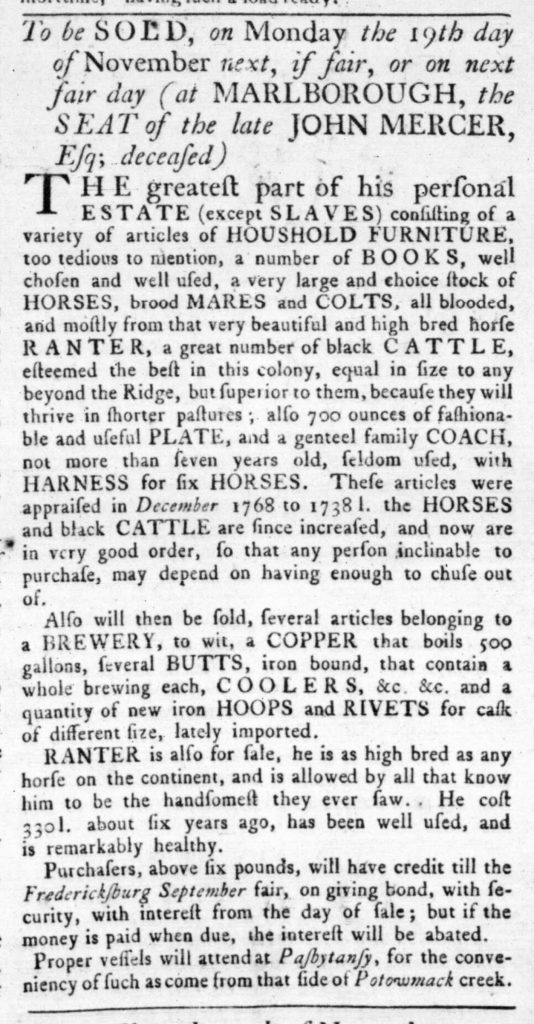

Despite the problems, in April 1766 Mercer took advertisements in the Virginia Gazette and the Maryland Gazette to promote the Marlborough Brewery’s “strong Beer and Porter at 18d and ale at 1s the gallon, Virginia currency, in cask, equal in goodness to any that can be imported from any part of the world,” and to give a kicking to the imported brew, declaring his own beer used “nothing but the genuine best Malt and Hops … without any mixture or substitute whatsoever, which, if the many treaties of brewing published in Great Britain did not mention to be frequently used there, the experience of those who have drunk those liquors imported from thence would point out to be the case, from their pernicious effects.”

Mercer revealed that he had spent “near 8000l to bring my brewery to its present state,” which, even assuming these were Virginian pounds, suggests an expenditure equivalent today to an enormous £1 million, and went on to say that “The severe treatment we have lately received from our Mother Country [a reference to the Stamp Act of 1765, introducing deeply unpopular taxes, and other revenue-raising legislation imposed on the colonies by London: Mercer was a committed and vociferous opponent of the Stamp Act], would, I should think, be sufficient to recommend my undertaking. (though I should not be able to come up to the English standard, which I do not question constantly to do).” The appeal to patriotic Americans to drink local porter in preference to imported was one that would be repeated by other brewers.

Bottles were a problem, and Mercer’s advertisement added: “Any person who sends bottles and corks may have them carefully filled and corked with beer or porter at 6s or with ale at 4s the dozen. I expect, in a little time, to have constant supply of bottles and corks; and if I meet the encouragement I hope for, propose setting up a glasshouse for making bottles, and to provide proper vessels to deliver to such customers as favour me with their orders such liquors as they direct, at the several landings they desire.”

Ignoring the problems with the quality of the beer produced at his brewery, Mercer remained optimistic, telling his son George: “It is affirmed that Virginia imports beer & ale to the amt of upwards of £30,000 Sterl. yearly (which is more than ten such breweries as mine could brew) little of what is imported is sold by any ordinary keeper who cannot import it on his own account, as there is little to be got by it, when purchased here whereas mine at 10d and 15d a gallon, to which I have reduc’d it upon the fall of exchange, will afford every ordinary keeper as much, if not more profit, than any other liquor he sells.”

He was also optimistic about starting his own glassworks to provide bottles for the brewery, telling George: “A Glass house to be built here must I am satisfied turn to great profit, they have some in New England & New York or the Jerseys & find by some resolves the New England men are determined to increase their number.” However, he was facing growing financial problems, despite employing a receiver to travel around northern Virginia calling on his debtors to try to recover the £10,000 he was owed. Still, he remained hugely optimistic, telling George early in 1768: “I can make my barley and hops, have coopers of my own, & beleive [sic] some of my own negroes coud malt & brew tho I shoud choose to employ an expert brewer & malster. Surely with so many advantages it is impossible I should fail, if I persevere.”

Just as the next brewing season began, however, in October 1768, Mercer died at home, leaving the heavily indebted estate in the control of his son James. James immediately started to sell off everything, from his father’s library of 1,200 books to his cattle and horses, including his prize stud horse Ranter, worth £330.

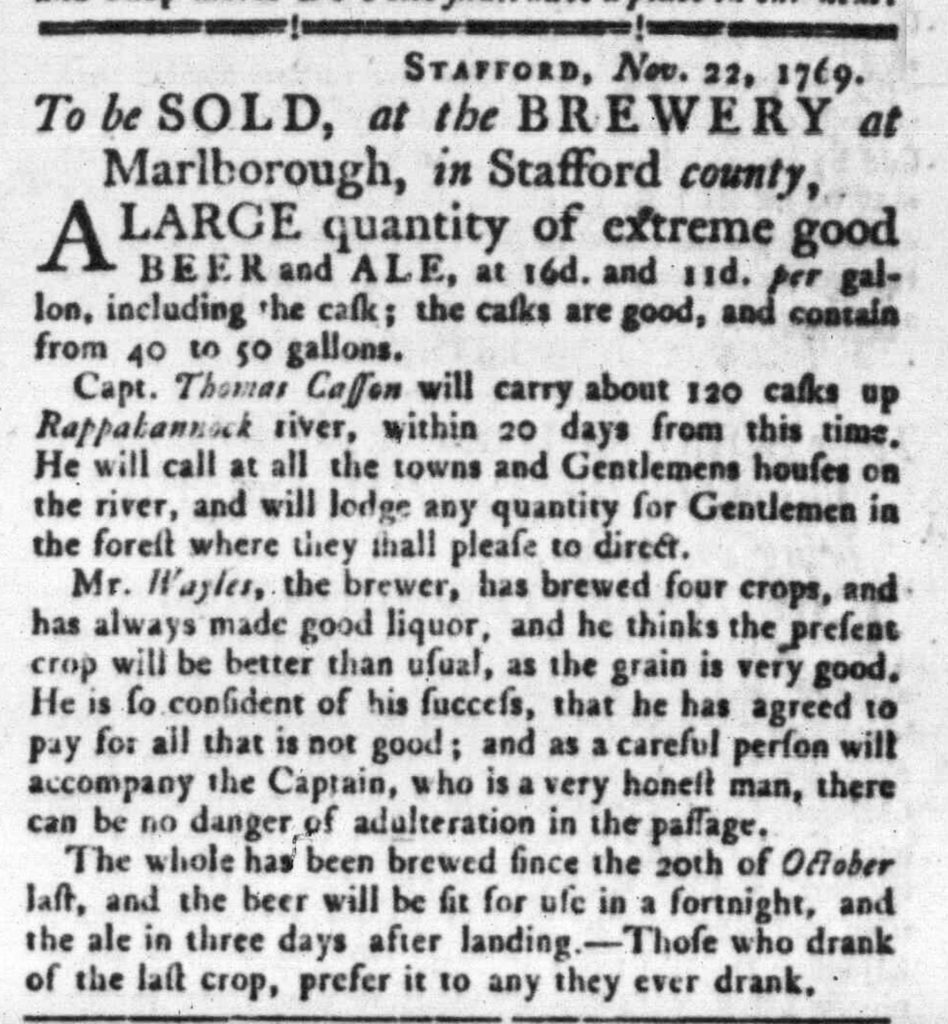

The brewery, however, kept going, under the control of Wales: on November 23 1769 the Virginia Gazette carried an advertisement from the Marlborough brewery for “a large quantity of extreme good beer and ale at 16d and 11d the gallon, including the casks; the casks are extremely good, and contain from 40 to 50 gallons.” “Mr Wayles the brewer” declared that he “has brewed four crops” (that is since the first in 1765) and has always made good liquor, and he thinks the present crop will be better than usual, as the grain is very good.” Indeed, “He is so confident of his success that he has agreed to pay for all that is not good … the whole has been brewed since the 20th of October last, and the beer will be fit for use in a fortnight, and the ale in three days after landing.” Such speedy maturation suggests the “beer” was now solely of the amber or pale kind, rather than porter. Would-be customers were told that “Captain Thomas Casson will carry about 120 casks up Rappahannock river within 20 days from this time,” and “he will call at all the towns and Gentlemens Houses on the river, and will lodge any quantity for Gentlemen in the forest where they shall please to direct.”

Commercial success clearly continued to elude the venture, and a year later, in November 1770, the brewery equipment, which included “a copper that boils 500 gallons, several iron bound buts [sic] that contain a whole brewing each, coolers, &c &c and a quantity of new iron hoops and rivets for casks of different forms, lately imported,” together with much of the rest of the estate’s assets, was put up for sale. The last echo looks to have come the following year, in August 1771, when among the items being sold at an auction of goods from the Marlborough estate were “about two Hundred Weight of Hops of last Crop.”) James Mercer, an important figure in the politics of revolutionary Virginia, and subsequently a judge of the state’s General Court, apparently continued to live at Marlborough until his death in 1791: the estate passed to his half-brother John Francis Mercer, a soldier and politician, who sold it around 1800, after which it decayed over the next couple of decades until it effectively disappeared.

Addendum: to learn more about the career of Andrew Wales, click here

More absolutely first-rate research Martyn.

Fascinating story – you are undoubtedly in a complete league of your own vis a vis British (and related, as here) brewing history.

*blush*

A fascinating account; thank you.

You’ve landed squarely on my turf here. Come on over and I’ll give you a tour of Williamsburg, modern Marlborough and the Rappahannock River. You’ve a landing pad and base of operations with us, as we’ve just moved back. There are plenty of very good breweries now to comfort the weary traveller.

This is a welcome story, even if they never did quite get their beer together.

I visited Williamsburg in 2016 for the beer history conference, which I am told by Frank Clark may be repeated next year, so I shall certainly take you up on that offer of a tour if it goes ahead …

This is fascinating. I think the claim regarding Hare is that it was the first brewery built specifically as a porter brewery during a time when there was that big race to build larger and larger vats (leading to the great London Porter Flood) because it wasn’t taxed as much as beer. Hare’s father had a porter brewery in London, where his son learned the trade. I don’t think taxes worked that way in America, so the porter “craze” didn’t happen here. Hare’s brewing notes are part of the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

I really enjoyed your article. Thank-you!

I have tried to get a look at those Hare brewing notes, which are apparently mislabelled “port recipe” rather than porter, but so far nobody seems to have got a peek …

[…] a bit of history was made this week as Martyn wrote the tale of a very early and not much good porter brewery in the US state of Virginia – which […]

Martyn, Thanks for this. Makes me feel like a complete idiot for reading these adds many times but never making the connection to the date! One of the thing that I always found the most interesting about Mercers advertisement was his insistence on commenting that it would be brewed only from the finest malt and hops and” without any mixture or substitution what so ever which if the great many treaties on brewing from Great Britain did not mention to be frequently in use there, the experience of those who had drunk the liquors imported from thence and had experienced their pernicious effects would point out to be the case.”

I guess this once again raises my curiosity about the use of adulterants in porter, It seems that even in the 18th century nobody really knew if or how much porter additives were being used. It may also just have been a little more patriotic propaganda to call English beer quality into question? I know the laws and that it was probably too much of risk for the largest London brewers to use them but the constant references have always made me think it wasn’t so cut and dry. This is especially true here in America were we do not see the same governmental restrictions on porter additives. I see a similar thing with chocolate makers who are accused of adding brick dust to their chocolate. Surely some must have done it or there would be no need for acts to prevent it but I guess my question is other than court records how do we find out about these cheaters?

Frank

Sorry to be late to the game in commenting on this post – I’ll blame COVID-19. This was an interesting read, as always, and points to the reality that “established” history often needs to be questioned. The point that Richard Wagner makes about Hare being the first porter brewery, rather than the first brewery making porter in America is a good one. Hare’s place as the first porter brewery is usually traced back to an assertion made by Stanley Baron, but Baron’s book is pretty broad-ranging in time and geography, and his access to sources was much more limited than now. So, he wasn’t necessarily digging deeply into every aspect of American brewing. Porter was regularly imported and sold in New York from pretty early on, so it’s clear that the taste for porter was here. In 1765 it’s noted that there were “two large breweries” in New York City “making beer after the manner of London Porter.” Unfortunately, there is no note of which breweries these were, but the likely candidates were Harrison’s on the North River and one of the Rutger’s breweries, although it could as easily have Robert Benson’s (they were all related by marriage in any event). These breweries all go back before the 1750s in terms of operation. In the 1770s when Jonathan Nash ran Rutger’s Maiden Lane brewery he advertised porter, and Samuel Atlee continued to make porter after taking over Harrison’s brewery in 1780. Atlee was the first to advertise “American Porter” in New York papers that I’ve seen, although Benjamin Williamson advertised “New-York Bottled Porter” in the mid-1770s (whether this was made in New York or just bottled in New York is a different question). Atlee’s whole push was a “buy American” thing, so that’s why he termed things as he did. All this to say that there’s a lot we don’t know, and probably won’t know, about who brewed what, when, etc., but pieces like yours really help to fill in the puzzle pieces.