In view of recent events, I thought people might be interested in a short history of Asahi Breweries …

Beer was introduced into Japan by the Dutch, who were the only Europeans allowed to trade with the country after the expulsion of the Portuguese early in the 17th century, and who would take biiru with them when they made their compulsory once-a-year trip from their base in Nagasaki to the Emperor’s palace in Edo (now Tokyo). However, it was not until Commodore Matthew Perry of the US Navy arrived in Japan in the 1850s to try to push the shogunate into opening diplomatic relationships with the United States that the locals made any proper analysis of this new drink, after the American delegation on Perry’s second trip to Japan in 1854 presented officials with gifts including three casks of beer. Japanese opinion was divided: one called it “magic water”, while another described the beer as “bitter horse-piss wine”.

Beer was introduced into Japan by the Dutch, who were the only Europeans allowed to trade with the country after the expulsion of the Portuguese early in the 17th century, and who would take biiru with them when they made their compulsory once-a-year trip from their base in Nagasaki to the Emperor’s palace in Edo (now Tokyo). However, it was not until Commodore Matthew Perry of the US Navy arrived in Japan in the 1850s to try to push the shogunate into opening diplomatic relationships with the United States that the locals made any proper analysis of this new drink, after the American delegation on Perry’s second trip to Japan in 1854 presented officials with gifts including three casks of beer. Japanese opinion was divided: one called it “magic water”, while another described the beer as “bitter horse-piss wine”.

The treaties signed between Japan and the US saw Yokohama opened from 1858 as a place for European traders to settle, and in 1863 military forces from Britain and France arrived in Yokohama to protect the increasing numbers of their nationals based in the city. Two years later, according to an article published in the China Mail newspaper in Hong Kong on October 19 1878, two foreigners, one an Englishman called Campbell and the other an American called Langthorne, began to brew beer in Yokohama, at the first commercial brewery in Japan. Campbell and Langthorne are deeply obscure and nothing more seems to be known of them, not even their first names. Their business did not last long, according to the China Mail, at least in part because of increasing imports of beer from Europe and America: the newspaper wrote that “either because in those days the foreign denizens of Yokohama were so rich or so extravagant as to despise any but the produce of the famed distant vats of Burton, Edinburgh and Dublin, or because the projectors had not sufficient knowledge of their art to make their liquor palatable, or capital enough to work and wait until it had created a reputation and a market, they soon abandoned their enterprise; and the buildings they erected were subsequently pulled down.”

In 1868, however, the wonderfully named Marinus Johannes Benjamin Noordhoek Hegt, born in the Netherlands in 1821, a sea captain and merchant who came to Yokohama in 1860, opened a small brewery at No 46 Bluff, part of Yokohama’s designated European district, where there was a deep well on the site. Hegt hired as his brewer Emil Wiegand, a brewer from Germany who had emigrated from Hessen at the end of 1853, aged 19, via Bremen, arriving in New York on January 6, 1854. Wiegand was apparently naturalised in Philadelphia in 1856, and looks to have spent 11 years in the eastern US, presumably working in local German-run breweries, before leaving New York on December 1 1867 to travel to California via Nicaragua. He spent barely a year in San Francisco before moving to Japan, arriving there, according to a deposition he made later in a tribunal at the US consulate general, in 1869 after signing a contract to manage the “Japan Yokohama Brewery”.

Hegt’s brewery inspired a man called William Copeland, born Johan Bartinius – sic– Thoresen in Tromøy, in southern Norway, in May 1834, to build a brewery of his own on the site first used by Campbell and Langthorne, No 123 Bluff, which had as its chief attraction a source of “singularly pure” water, and which became known as the Spring Valley Brewery. Copeland, who had arrived in Japan in 1864 (and whose middle name changed to Martinius at some point) made his first brew in January 1870, shortly after Hegt had moved to larger premises at Bluff lot 68 in 1869. The two rival breweries ran in competition with each other until June 1876, when the owners agreed to a merger, and Copeland and Wiegand brewed at the Spring Valley Brewery site, using Bluff lot 68 as a maltings, until the maltings were destroyed by fire in 1877.

Hegt’s brewery inspired a man called William Copeland, born Johan Bartinius – sic– Thoresen in Tromøy, in southern Norway, in May 1834, to build a brewery of his own on the site first used by Campbell and Langthorne, No 123 Bluff, which had as its chief attraction a source of “singularly pure” water, and which became known as the Spring Valley Brewery. Copeland, who had arrived in Japan in 1864 (and whose middle name changed to Martinius at some point) made his first brew in January 1870, shortly after Hegt had moved to larger premises at Bluff lot 68 in 1869. The two rival breweries ran in competition with each other until June 1876, when the owners agreed to a merger, and Copeland and Wiegand brewed at the Spring Valley Brewery site, using Bluff lot 68 as a maltings, until the maltings were destroyed by fire in 1877.

The Spring Valley Brewery made lager during the summer, and “‘English ale’, ‘Bock’ and ‘Bavarian’ beer, demanded by the better sort of customer” during the winter. The beer was exported to Tokyo, Nagasaki and other Japanese towns, and as far away as Shanghai and Hong Kong. Copeland and Wiegand brewed together as co-partners until the end of 1879, when Wiegand filed a bill with the US consular court in Yokohama for a dissolution of the partnership, alleging “fraudulent acts and other irregularities” by Copeland. The American consul general, who had the legal right to hear cases in Japan involving American citizens, found Copeland not guilty, but it was agreed that the partnership should be dissolved anyway and the firm wound up, with its assets sold. The brewery was estimated to be worth some £32,500, and Wiegand, who had bought much less to the partnership than Copeland, was due $6,250 of that. Unfortunately the only bidder for the brewery was Copeland, who bought the business back in February 1880 for just $12,000, which meant that not only did Wiegand not get anything, he now owed Copeland several thousand dollars. Wiegand eventually died in San Francisco in 1887, aged 47.

In 1880, meanwhile, Copeland was involved in another lawsuit between himself and his head clerk, which was again settled by the US consul in favour of Copeland. However, the suit bankrupted the Spring Valley business, and though Copeland continued brewing by himself until 1882, the business went under in an economic recession. Two years later, on July 1884, the Spring Valley brewery was sold by the US Marshall by order of the US Consular Court for $11,500. The London and China Telegraph of September 22 1884 wrote that “this property is estimated to have cost the late proprietor over $60,000.” Who bought it remains unclear, but on April 27 1885 the London and China Telegraph reported that two fires had recently broken out at the premises of the Spring Valley Brewery on the Bluff, Yokohama, and in the first, which began at 8pm on March 13, the block was destroyed which housed in its lower portion the “extensive” brewery plant. The plant and buildings were insured for $5,000 in the Lancashire and the City of London Insurance Companies, but “the brewery plant could not be replaced for at least three times that amount.”

Two months after the fire, in May 1885, the first meeting was held of resident foreigners in Yokohama that would eventually lead to the foundation of the Japan Brewery Company Ltd, set up with mixed Japanese and foreign investment. This company quickly acquired the Spring Valley brewery site to build its own brewery, taking advantage of the site’s water supply. The new concern eventually launched its “Kirin beer” in 1888, and changed its name to Kirin in 1906.

Two months after the fire, in May 1885, the first meeting was held of resident foreigners in Yokohama that would eventually lead to the foundation of the Japan Brewery Company Ltd, set up with mixed Japanese and foreign investment. This company quickly acquired the Spring Valley brewery site to build its own brewery, taking advantage of the site’s water supply. The new concern eventually launched its “Kirin beer” in 1888, and changed its name to Kirin in 1906.

By now the Japanese brewing industry had become thoroughly “Nipponised”, helped by men such as Nakagawa Seibei. Nakagawa (in Japan, surnames are given first) travelled at his own expense from his homeland to Germany in 1872, hoping to learn a foreign skill he could use back in Japan. He was advised to study brewing, and spent more than two years, from 1873 to 1875, at a brewery in Fürstenwald owned by the Berlin brewery Tivoli.

It is difficult to imagine what it must have been like for Nakagawa, who was only 24 when he arrived in Germany, where everything – the language, the architecture, the food and drink, the clothing, the entire way of life – was utterly alien to all he had known previously. On his return to Japan with a certificate of study from the Tivoli brewery, Nakagawa was hired by the Japanese government to build a brewery in the newly founded city of Sapporo, on the northern island of Hokkaido, which was being rapidly developed in response to a possible invasion threat from Russia. The brewery made its first German-style lager in 1876, and was sold by the government to private investors ten years later.

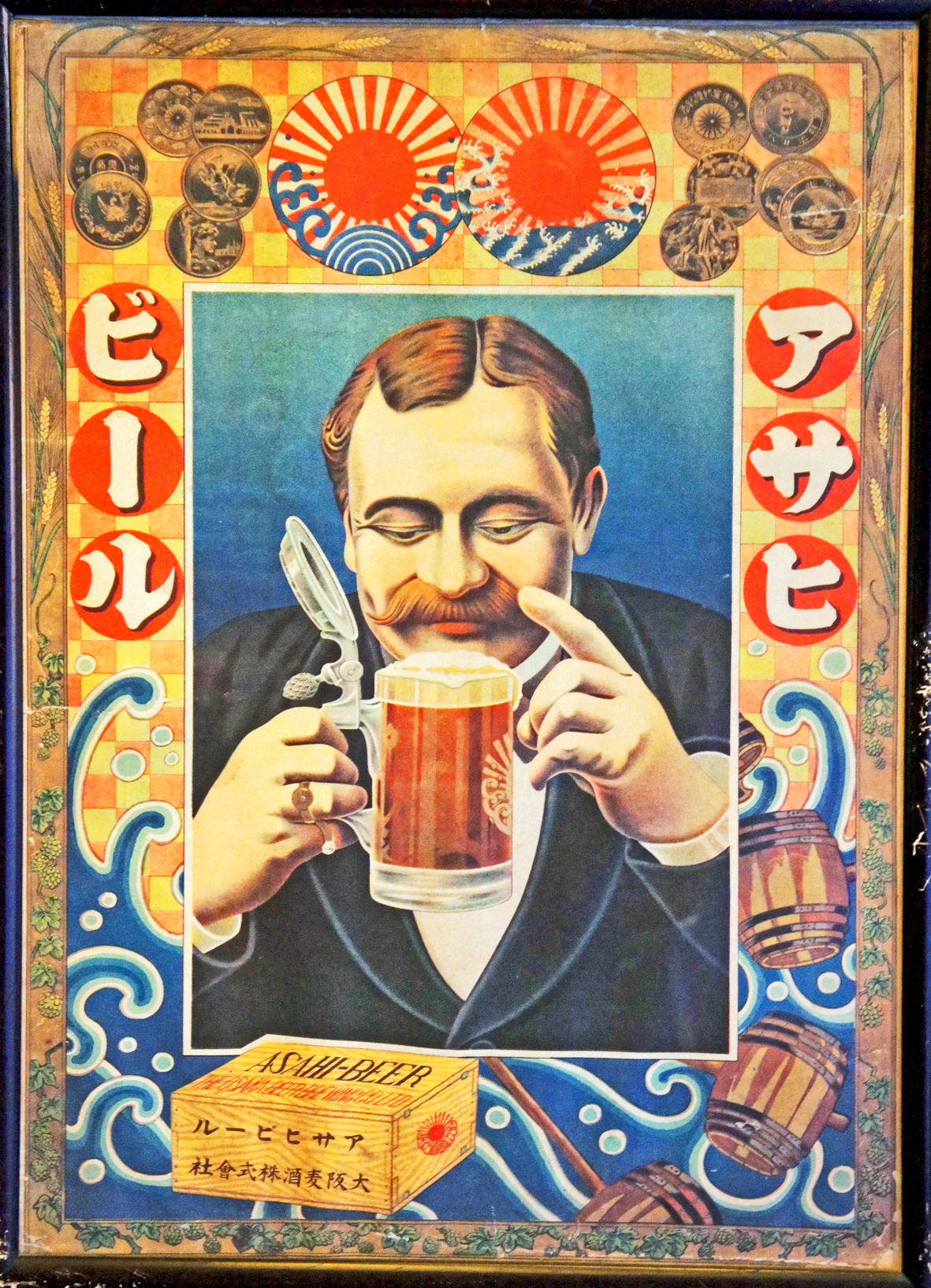

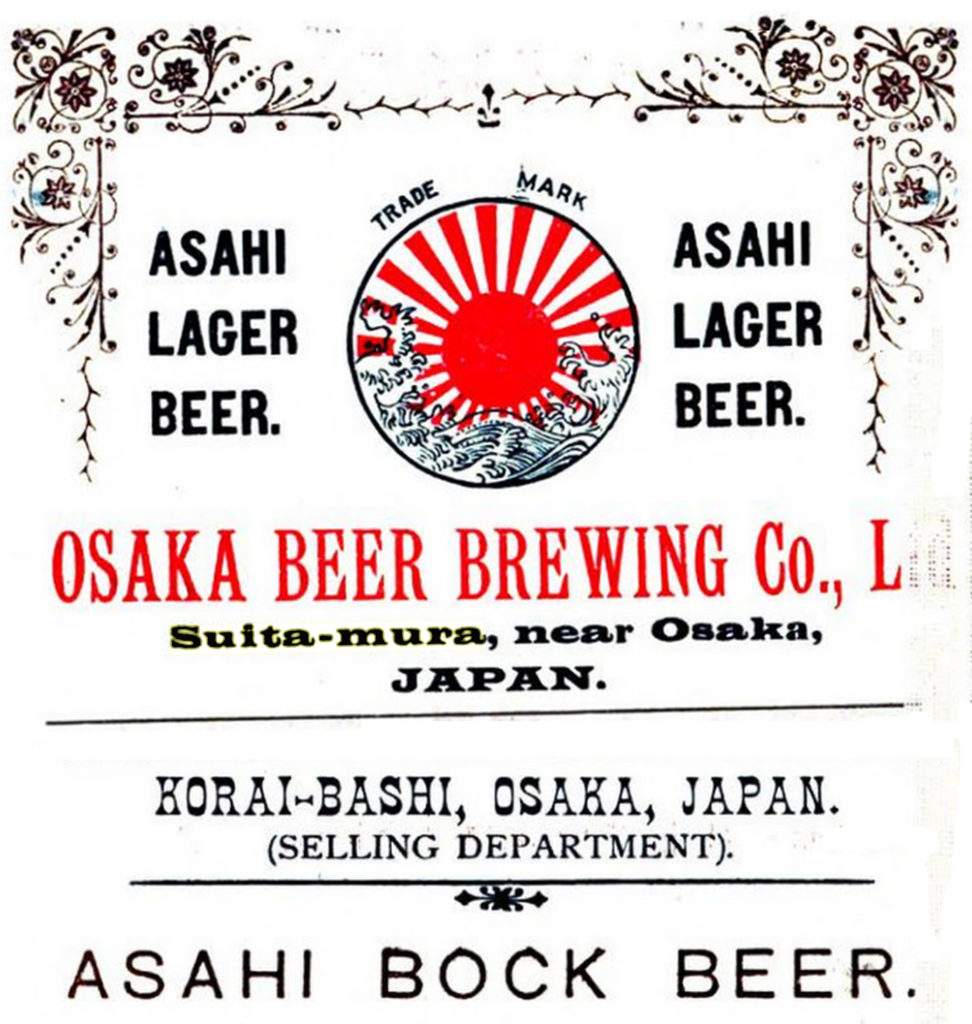

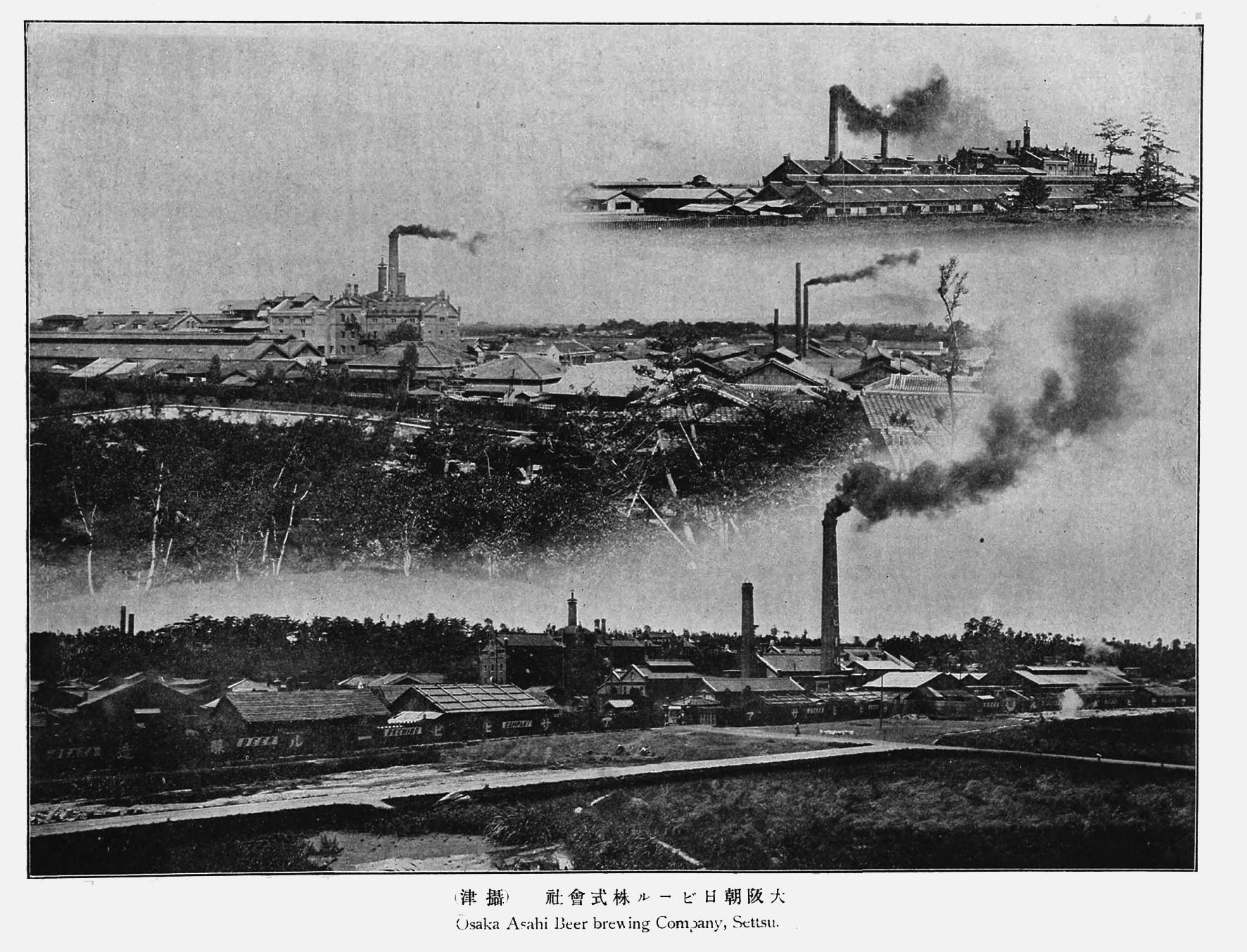

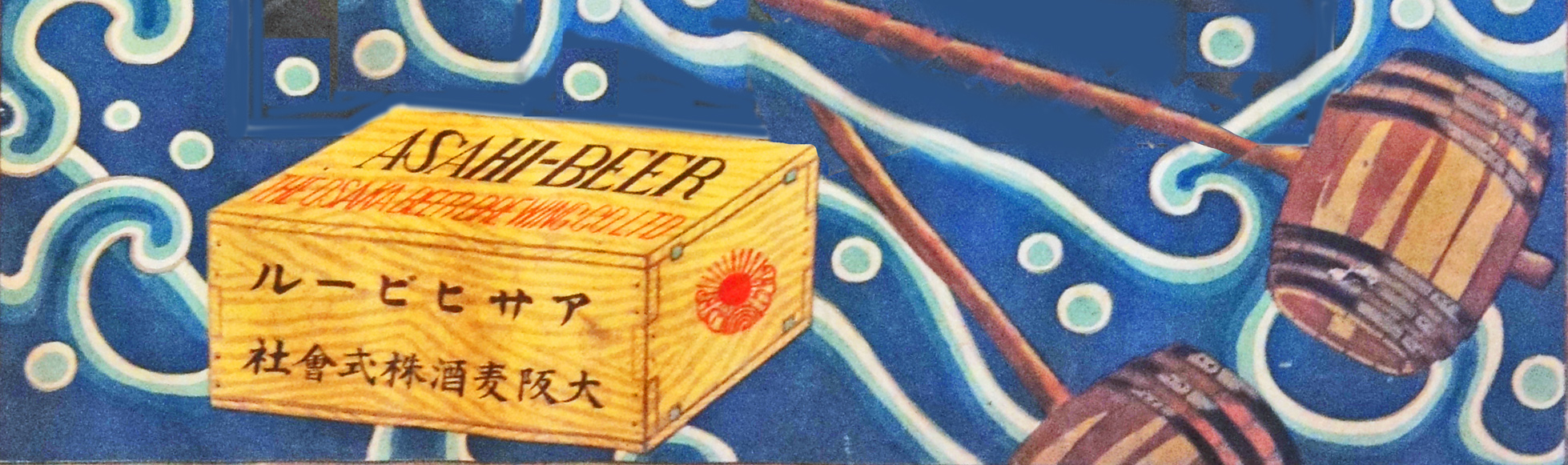

Between 1869 and 1872 there were more than a hundred brewery start-ups in Japan, most being small and deeply obscure, with very little now known about them. All, or at least all those about whom sufficient details are known, concentrated on producing German-style beers, mostly because Japanese beer drinkers needed the reassurance that domestic brewers were using the same techniques and ingredients as foreign brewers in order to buy Japanese-brewed rather than imported beer. Among the start-ups was one begun by Torii Komakichi, a well-known sake brewer from Sakai, south of Osaka, a city in the south-central region of Japan’s main island, Honshu. In 1888 Torii’s Osaka Beer Brewing Company sent Ikuta Hiizu to Germany to study brewing at the brewery school in Weihenstephan, Bavaria. Ikuta returned to Japan in 1889, where he was appointed manager and technical director of a new brewery built at Suita Mura, on the edge of Osaka, which was completed in 1891. The plans for the brewery were drawn up in Germany, although it was built by an Osaka constructor, and all the brewing machinery was from Germany, though most of the malt and hops was imported, initially, from the US west coast.

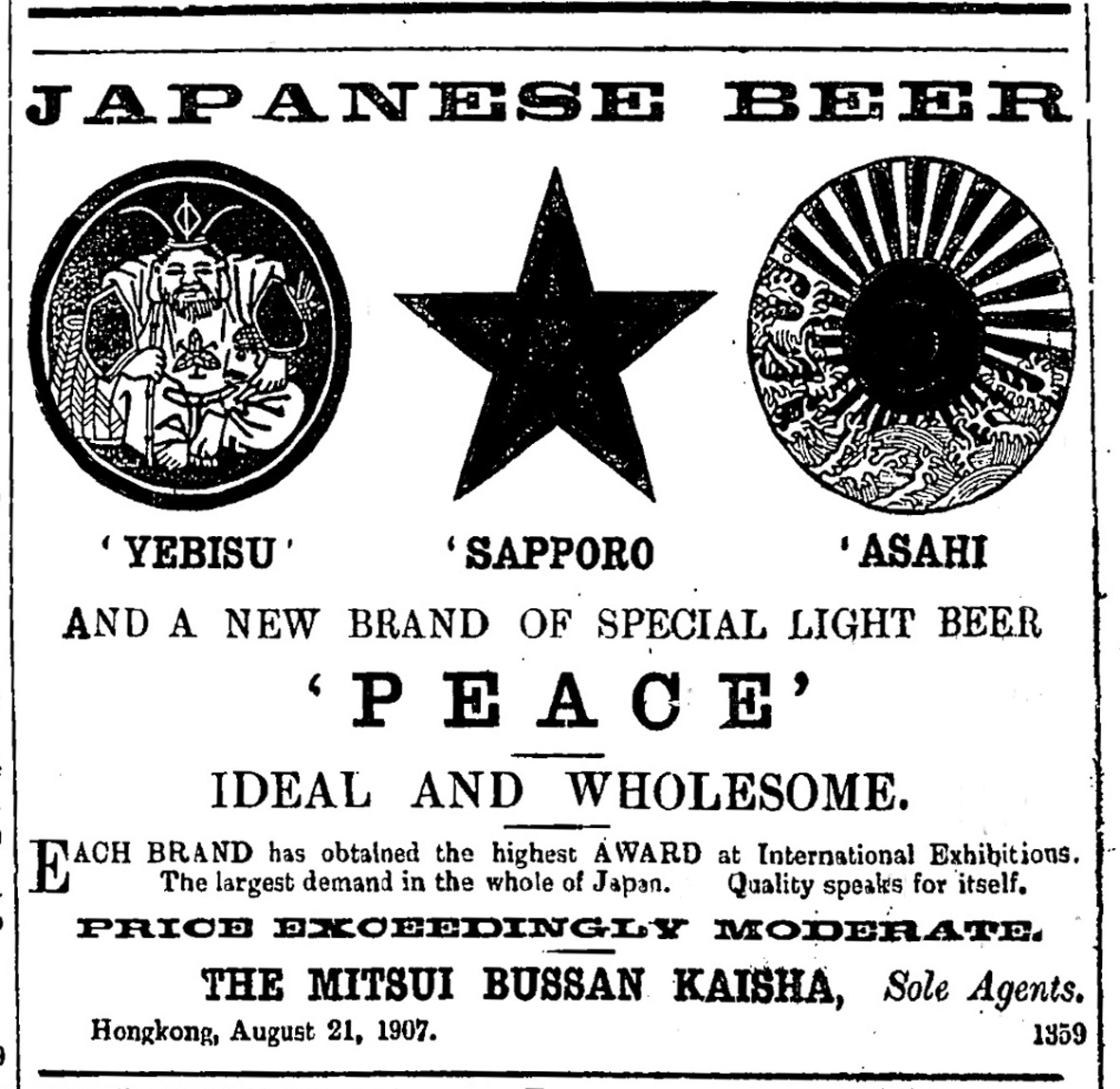

In 1892 the company launched a beer under the name Asahi, meaning “morning sun”. The Osaka brewery showed its beer at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, where it was noted that the company was using Japan-grown barley of the Golden Melon variety, which stood up to the hot and humid climate of Honshu, and which had been introduced into the country from the United States in 1885. The same year Osaka was reorganised as Osaka Breweries Ltd. An “Asahi Beer Hall” was opened in nearby Kyoto in 1896 to promote the company’s beer to thirsty tourist. By 1901 it was the second biggest brewery in Japan, at 53,500 hectolitres, well ahead of the Japan Brewery Company/Kirin at 28,500hl and Sapporo at 24,517hl, but behind the Nippon Beer Co of Tokyo, whose main brand was Yebisu, on 59,450hl.

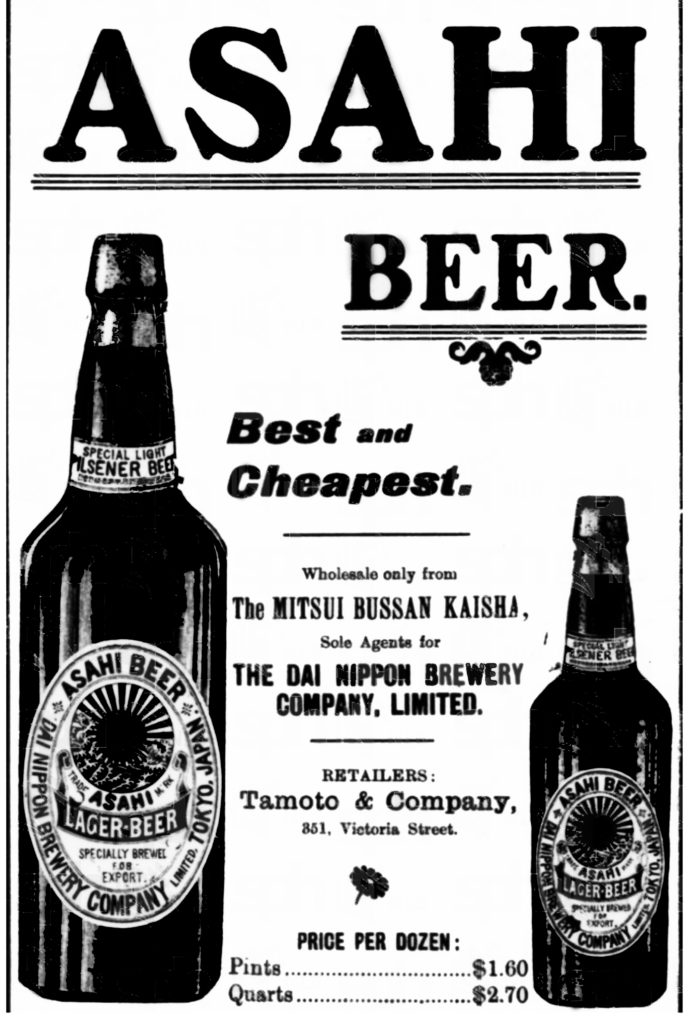

The same year the Japanese government introduced a “brutal” new beer tax, which hammered the smaller brewers. The “big four” battled on, but in 1906, in an attempt to reduce competition, which was damaging profits, Sapporo, Osaka Beer Co and Nippon Beer agreed to merge under the name Dai Nippon (“Greater Japan”) Beer Company. From then until after the Second World War, the Japanese beer industry was almost totally dominated by Dai Nippon Beer and Kirin, both producing – until 1941, at least – heavily German-influenced beers. However, the pair were unable to stop retail outlets conducting a vicious price war. This only ended in 1933, when the two giants of Japanese brewing signed an agreement to form the “Co-operative Beer Sales Company Inc”, a deal brokered by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, which gave Dai Nippon 70 per cent of joint sales and Kirin 30 per cent. In the total market, Dai Nippon had a 56 per cent share and Kirin 28 per cent, giving the Co-operative Beer Sales Company 84 per cent of the domestic Japanese beer market. Through the 1930s Asahi and Kirin fought each other for the title of Japan’s best-selling beer brand, with Asahi on an average of 30 per cent of the market and Kirin on 27.5 per cent. Meanwhile Dai Nippon Beer’s Asahi division was opening new breweries, in Hakata, Fukuoka, on Japan’s southernmost large island, Kyushu, in 1921 and Nishinomiya, a few miles from Osaka, in 1927.

When Japan went to war with China in 1937, a conflict which eventually widened into bitter conflict with the United States and the UK in 1941, the beer industry in Japan became more and more tightly controlled by the government, not least because through taxation it generated essential funds for the war effort. In 1939, sake was still the dominant alcoholic beverage in Japan, selling 4.5 times as much as beer, which was largely an expensive middle and upper-class luxury. But as rice production was diverted into foodstuffs, sake production was halted by the end of 1940. Beer took its place, since barley was only a grade-B foodstuff. At the same time, with supplies of hops no longer available for import from Germany, Japan’s brewer began to make their beers less bitter. Small brewers disappeared completely, leaving only Dai Nippon and Kirin by 1943.

After Japan’s defeat in 1945, in the seven-year occupation that followed, much effort was made by the occupiers to break up Japan’s economic conglomerates, the zaibatsu. Dai Nippon did not wait to be broken up, instead putting forward its own arrangement in which, in 1949, it split into two, one side taking the Asahi brand, the other, initially called Nippon Breweries, the Sapporo and Yebatsu brands. Asahi had 36 per cent of the market, Nippon Breweries 38.7 per cent and Kirin 25.3 per cent. The three operated an informal cartel that eliminated price competition, while Japan’s ministry of finance kept import duties on foreign beers high, with an (under world trade rules, illegal) agreement that the three brewers would, as a quid pro quo, buy expensive Japanese-grown barley rather than much cheaper foreign barley.

Until the middle of 1949, the occupying forces had barred Japanese from going to restaurants, bars or beer halls. The reopening of the “on-trade” saw beer sales boom: one bar in Osaka was selling 120 wooden crates of 24 bottles each night, an entire truckload in a day. In 1954 Asahi began to pull ahead of its rivals, capturing 37 per cent of the market, after leading the way in marketing efforts that included sponsoring radio and television programmes, films (including Gone With the Wind when it returned to Japanese cinemas in 1952) and boxing matches. In 1958, Asahi introduced Japan’s first canned beer. Meanwhile the Japanese alcohol market was changing, with sake falling from 71 per cent of all alcohol beverages sold before the Second World War, against beer’s 16 per cent share, to 29 per cent in 1959, against beer’s 44 per cent.

As well as canned beer (which today has more than 60 per cent of the Japanese market), Asahi also pioneered the first outdoor fermentation and lagering tank, the “Asahi Tank”, launched in 1965 and soon licensed to a German brewery construction firm, Ziemann.

By now Asahi had seen its share of sales drift down, leaving it with just 27.9 per cent of the Japanese market in 1961, barely ahead of Sapporo on 27.8 per cent, while Kirin had 41.7 per cent. Kirin’s dominance enabled it to set prices that hampered its rivals’ attempts to match them and still be profitable, and by the mid-1980s its share of the market was more than 60 per cent, with Sapporo on 20 per cent and Asahi on 11 per cent, while Suntory, a distiller that had entered the beer market in 1963, had seven per cent.

At the same time, the beer produced by the three firms continued to be the comparatively light, lightly hopped drink Japan’s brewers had been forced to change to during the Second World War, a style of beer which both proved popular with the increasing numbers of women drinkers, and beer rapidly left sake sales far behind. While the trend in the 1950s and 1960s towards less-bitter beers could be also seen in, for example, the United States, from the 1970s, Japan’s brewing industry began to exhibit some peculiarly Japanese developments. One was the introduction of “beer-like” brews, or happoshu (literally “sparkling spirit”), containing little or no barley, a reaction to both the high price of barley itself and the high taxes on barley brews in Japan. Another was the rise of “draught-style” bottled and canned beers from the late 1970s, with Asahi launching its own Draft Beer brand in 1986.

This did not stop Asahi striking deals with brewers elsewhere in Asia: in 1971 it signed an agreement with United Breweries of New Guinea that saw a brewery built in Port Moresby to make Asahi beers, and in 1986 another contract was signed with San Miguel to start brewing Asahi brands in Indonesia. In 1990 Asahi bought just under 20 per cent of the Australian beer giant Foster’s Group (sold in 1997 back to Foster’s).

What saved the company, however, was the introduction of “dry beer” in 1987 to try to compete with Kirin, which by then had 63 per cent of the domestic market, with Asahi far behind in third place on just 10 per cent. In 1982 one of Japan’s leading banks, Sumitomo Group, which held 12 per cent of Asahi’s shares, sent in a bank executive specialising in corporate turn-arounds, Murai Tsutomu. Murai made the brewery conduct market surveys which came back with the message that 98 per cent of beer drinkers surveyed wanted Asahi to change the taste of its beer. Drinkers said they wanted a beer that was rich but left no aftertaste. Asahi’s brewers told Murai that was not possible. Murai insisted that it had to be done, and the result was Asahi Super Dry, stronger, at 5 per cent alcohol, than most Japanese mainstream beers, generally 4.5 per cent, but with less sugar, sharper and with no aftertaste. It became instantly popular, particularly among younger drinkers. The launch doubled Asahi’s share of the domestic beer market in a year, and sent it to 37 per cent by 2001. This was the only Japanese brewing initiative to have any impact overseas, with US and European brewers also introducing “dry” beers: by 1990 there were more than 20 “dry” beers on sale in the US market.

Japan’s brewers had been protected for many years from new entrants into the market by a law that required a minimum annual output for anyone wanting a brewery licence of 20,000 hectolitres. In 1994 the country’s Ministry of Finance cut that requirement to just 600 hectolitres, making it viable at last for new microbreweries to start up. The first opened in Japan in 1995, and by 1999 the country had 242 new small breweries. In an attempt to head off this new competition, in 2001 Asahi opened its own “microbrewery” operation, Sumidagawa Brewing, a brewpub in Tokyo.

Super Dry was launched Canada in 1994 and the United States in 1995. It went into in 12 European countries in 1997, and in 2000 Asahi struck a deal with Bass in the UK for a Czech subsidiary of Bass to brew Super Dry under licence. But with the UK becoming the biggest market for the beer in Europe, in 2005 production was switched to Shepherd Neame in Kent. Meanwhile at home beer sales were falling, with the “big four” of Asahi, Kirin, Sapporo and Suntory suffering a volume decline between them of 23 per cent between 1994 and 2000. At the same time, sales of the cheaper happoshu were climbing, hitting 30 per cent of the Japanese beer market in 2001, the year Asahi finally launched a happoshu of its own. Two years later sales of happoshu for home consumption passed those of “real” beer.

Asahi had regained the number one spot among Japan’s brewers in 1998, and its share of the “real” beer market rose past 50 per cent by the end of 2008, though its share of the total “beer-like” market was only 37.8 per cent, barely ahead of Kirin on 37.2 per cent. Domestic beer sales were badly hit by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, and took several years to recover, but Asahi was seeing big rises in sales to China, where increasing affluence was powering what was becoming the biggest market for beer in the world. It began acquiring shares in five Chinese breweries in 1994 and 1995, and entered into an agreement with the then largest brewer in China, Tsingtao Brewery, to build a brewery in Shenzen, near Hong Kong, which opened in 1999. In 2009 it bought a 19.9 per cent stake in Tsingtao Brewery, reviving a link from before the Second World War, when Dai Nippon Beer Company owned Tsingtao.

Asahi had regained the number one spot among Japan’s brewers in 1998, and its share of the “real” beer market rose past 50 per cent by the end of 2008, though its share of the total “beer-like” market was only 37.8 per cent, barely ahead of Kirin on 37.2 per cent. Domestic beer sales were badly hit by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, and took several years to recover, but Asahi was seeing big rises in sales to China, where increasing affluence was powering what was becoming the biggest market for beer in the world. It began acquiring shares in five Chinese breweries in 1994 and 1995, and entered into an agreement with the then largest brewer in China, Tsingtao Brewery, to build a brewery in Shenzen, near Hong Kong, which opened in 1999. In 2009 it bought a 19.9 per cent stake in Tsingtao Brewery, reviving a link from before the Second World War, when Dai Nippon Beer Company owned Tsingtao.

An Australian craft beer brewery, Cricketers Arms, in Melbourne, was acquired in 2013, followed by a second in 2015, Mountain Goat Beer in Richmond, Victoria. The next year, as part of the fall-out from AB InBev’s acquisition of SAB Miller, Asahi bought SAB Miller’s beer business in Western Europe, including Peroni in Italy, Grolsch in the Netherlands, the St Stephanus “abbey” brand from Belgium and, in the UK, Meantime Brewing Company, for a total of $2.9 billion. Meantime, based in Greenwich and founded in 2000, had only been bought by SAB Miller two years earlier, for £125 million. Early in 2017 Asahi swallowed SAB Miller’s Eastern European business as well, including Pilsner Urquell in the Czech Republic; Dreher Breweries in Hungary; Ursus Breweries, the biggest beer brewer in Romania; Tychy and Lech in Poland; and Šariš in Slovakia, for another $7.8 billion. The deal made Asahi the third biggest brewing company in Europe, with 9 per cent of the market, after Heineken and Carlsberg. The same year it sold off its interest in Tsingtao for $844 million, as part of a general pull-out from the Chinese market to concentrate on Europe.

Earlier this week it was announced that Asahi had acquired the brewing assets of the London-based craft ale specialist, family brewer and pub and hotel owner Fuller, Smith & Turner, for £250 million. The deal includes the brewery in Chiswick, but not, it is speculated, the entire brewery site. It gives Asahi ten breweries in Europe, against the eight it runs in Japan, including the Hokkaido brewery in Sapporo, opened in 1970; Ibaraki, on the coast north-east of Tokyo, opened in 1991; and on Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, opened in 1998. It is currently the biggest brewer in Japan, fifth biggest in Asia and seventh biggest in the world.

Very thorough, as we’ve come to expect.

The paucity of comments (so far) leads me to think Asahi evokes little love among the cognoscenti. Its reach in Europe, which encompasses some reputed names, as you well-limned, justifies a revision of this view.

This tid-bit may interest, which I came across the other day when searching something else. It involves a dispute before a consular court between two foreign parties resident in Japan. One was the brewer Hegt, the other was Copeland, also a brewer.

It sheds light on c.1880 brewing practices in Yokohama and elsewhere in the region, especially the use of English materials and, evidently, top-fermentation.

It’s the very kind of problem raised in the case that no doubt greatly spurred lager-production in Asia.

https://books.google.ca/books?id=fSFCAQAAMAAJ&pg=RA1-PA439&dq=copeland+beer+Yokohama&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi8p9-FhZbgAhXL54MKHYS-Bj8Q6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=copeland%20beer%20Yokohama&f=false

Very interesting indeed, Gary, all the characters in that story, including Harryman and Eyton, appear in directories of the time: strange that despite the court case between Copeland and the Hegt brewery, the two should merge a short tim afterwards.

I enjoy Asahi, which is contract brewed in the US by Anheuser/Busch. Way tastier than their own brands, IMO.

Hi there… just a small correction, Asahi in the US is either imported directly from Japan or brewed by Molson in Canada (depending on the type of package). Kirin in the US is contract brewed by A.B., however.

We spent ten days in Japan about ten years ago visiting our son, who was stationed there with the US Navy, and tried a number of beers and sakes. Yebisu stood out clearly to my taste, especially on draft. It seemed to be in the Dortmunder style. I learned that it is pronounced A-B-Soo. I sought it out and drank a lot of it.

Do you have links to the references you utilized?

They’re all easy to find online, which is where I found them.

good article

Is that Marinus Johannes Benjamin Noordhoek Hegt in the Beer Poster above?

I wouldn’t think so – the features are rather oriental

A weird coincidence, because the figure looks exactly like my 2xGreatGrandfather William Adrian Johannes Noordhoek Hegt Brother of Marinus Johannes Benjamin Noordhoek Hegt.

Thanks for your reply