Sitting 30 feet below the surface at a table in a workmen’s refuge dug out of the soft Bohemian sandstone, drinking unfiltered, unpasteurised lager made in 80-year-old open wooden fermenting vessels and poured from big copper jugs, I reflected on how long it had taken me to make this journey. Being a beer writer who has never visited the Czech Republic is highly embarrassing, like being an art historian who has never seen Florence. But every attempt I had made to get to the birthplace of pale lager, in more years of trying than I want to recall, had gone wrong: until now. Another tick on the bucket list, at last.

Two ticks, actually: one for finally getting to the Pilsner Urquell brewery, and its fabled caves, and another for finally drinking at U Fleků, Prague’s almost legendary home-brew pub, eulogised by Michael Jackson 40 years ago in the first edition of the World Guide to Beer and somewhere I had wanted to drink ever since I read about it. The gods of beer guided my hand: it turned out the hotel I had booked in Prague, based solely on a balance of cheapness and closeness to the city centre, was just two minutes from U Fleků (which looks to translate as “The Spot” – as in “hits”, perhaps …).

Reviews I had read years ago suggested the locals at U Fleků did not appreciate all the tourists disturbing their drinking, but on a warm Central European afternoon, parked at one of a dozen big black trestle tables in the pub’s tree-shaded central courtyard sipping a cool glass of Flekovské pivo, the only beer U Fleků makes, a typically fine Czech dark lager, I noticed no such vibe: possibly because the place was still pretty quiet, and tourists were the only customers. But the waiters were attentive, the beer both cheap (compared to West London) and excellent, the snacks first-rate (based on my deep-fried beery cheese) and even the twinkling elderly accordianist over on one side of the courtyard wasn’t too irritating. I need to go back when the place is busier and sample drinking in one of the pub’s big refectory table-filled rooms, all empty of customers when I was there, but it was a good start to my first visit to Prague.

Next for something completely different: this was a trip organised by the Brewery History Society, ably aided by Max “Pivni Filosof” Bahnson, Argentine-in-exile and author of Prague: A Pisshead’s Pub Guide (a fine book, apart from the dodgy maps), who was acting as our cicerone and translator. Max had suggested we all meet in Hostomická nalévárna, a pub in Prague Old Town that acts as the brewery tap for the “resurrected” Pivovar Hostomice, based in the town of the same name south-east of Prague, which, like a lot of new Czech breweries, makes only classic Czech lagers. (The Czech drinker, as well as topping the table for the most beer consumed per head, at 142 litres a year, 40 per cent more than the Germans and more than twice as much as the UK’s frankly paltry 67 litres, is also the world’s most conservative beer consumer, it appears: IPAs are starting to become popular, but with a distinctly Czech spin – more bitter, less floral than the American version.) Hostomická nalévárna is pretty much your basic Czech locals’ boozing bar, which is surprisingly similar to your basic British locals’ boozing bar, plainly decorated in the dark-brown-and-cream colour scheme Richard Boston identified as the classic pub look, matchboarding walls, furnished with utility as the prime intent, and excellent for that reason: there are fewer and fewer places like this left in Britain, something to be regretted as gentrification sweeps the simple boozer down the drain.

Max, who is another old internet friend I had “known” for years before finally meeting him on this trip, then took us to Prague’s newest own-brew restaurant, Lod’ Pivovar, which is actually on a boat moored in the Vltava river – something you could guess if you spoke Czech (I don’t), as lod’ means ship. I wasn’t taking notes, so I can’t tell you about the beers, though the brewing kit, which filled much of one of the boat’s decks, looked beautiful: if you want to know more, read Max’s blog review.

This being the BHS trip to Bohemia, old breweries, rather than new ones, were our primary target, and the next day Max led us on a two-hour train-and-bus journey to the small village of Kostelec nad Černými lesy (which translates as “Churchtown underabove the black forest”). The Czechs’ vast consumption of beer means that even small communities – Kostelec’s current population is fewer than 4,000 – had big breweries: Cernokostelecký pivovar was producing more than 62,000 hectolitres a year before it was closed in 1987 after the wood-fired brewery boiler packed up and was decreed too expensive to repair. In 2001 a Czech beer historian, Milan Starec, and some colleagues acquired the brewery site to use as a home for old brewing artefacts, and have been working to restore it under the name Černokostelecký zájezdní pivovar. In the meantime a microbrewery, Minipivovar Šnajdr has been installed in part of the old brewery premises; it produces a draught dark beer, Černá svině (“Black Swine”) and a bottled Baltic Porter, imperial stouts being one of the “craft” styles the Czech drinker appreciates.

Milan himself took us round the brewery, starting in the restaurant, which has a tremendous collection of old Czech breweriana on its walls from dozens of now-closed breweries (and lavatories that contain repurposed malt-barrows, japonky in Czech, as washbasins), then on to the huge and frankly beautiful polygonal malt-mill, once horse-powered, and built as a result without a single internal column so nothing would get in the way of the horse as it trudged on its daily circular journey (the bracing in the roof is a carpenter’s dream) and the maltings, which contain the only granite steeping tank I have seen. The main brewery building was filled with ancient kit: huge disused coppers, mash tuns and lauter tuns, enormous coolships, and the biggest vertical cooler I have ever come across, around seven feet high and eighteen feet long.

Milan told us that the coolships would take the hot wort down to around 60ºC, and the vertical cooler, which had cold water running through the interior as the wort ran down the outside, would drop it to 9ºC. Once cooled, the wort was run into open fermenting vessels – old-fashioned even when the brewery closed – before being lagered in huge casks in the permanently cold cellars below the brewery. The cellars also contain some original, long-disused wooden fermenting vessels; and a new microbrewery, which opened on New Year’s Eve 2013 and is named for one of the people involved in its construction, Jaroslava Šnajdra.

The next day was another train journey, out to Pilsen. Bizarrely, the bus is faster: the train takes almost 1hr 40mins for a journey of just over 50 miles. But with the average age of BHS Team Bohemia well past the half-century mark, we older travellers like to ensure our comfort breaks will be properly catered for. As an official trip to the Pilsner Urquell brewery, the six of us had our own guide, a very nice young woman called Markéta, though, alas, we could not get to see the brewery archives, as all the archive staff were “on holiday”. The story of Pilsner Urquell should be too well known for me to have to repeat it: the town the Czechs call Plzeň is ground zero for the style of pale lager known as pilsner, invented here in 1842 at the newly built Citizens’ (or Burghers’) Brewery (Měšťanský Pivovar in Czech, Bürgerliches Bräuhaus in German) by combining English malting techniques with Bavarian cool bottom-fermentation and cold maturation to make a brew that is parent to 90 per cent of the beer drunk today. It is, therefore, correctly, a place of pilgrimage, with three quarters of a million people visiting the Pilsner Urquell brewery every year – 2,000 a day. Unsurprisingly, rather than have those thousands wander around the site, visitors are bussed around. More surprisingly, perhaps, the place is so big, there is enough space for all the trippers to not keep tripping over each other.

For lovers of shiny copper (and who isn’t?) the Pilsner Urquell brewery is a marvel: lots of lovely big copper vessels in the old part, lots of even bigger copper vessels in the new part, plus a couple of massive stainless steel lauter tuns. Then it’s down into the cellars, where once all the beer the brewery produced was fermented and lagered, through a doorway dated 1839, when the construction of the brewery started. If you get lost in the miles of cellars, says Markéta, just follow the flow of the water that runs in gutters down the passageways and you will come to the entrance.

Here a small amount of beer is still made the old way, in open wooden fermenting vessels, and lagered in big wooden vats lined with pitch to stop the flavour of the wood getting into the brew: (Markéta was surprised when I told her than British brewers never lined their wooden casks.) The beer brewed in the cellars is made old-style to give something to check the lager made in the new brewhouse against: theoretically the one should taste just like the other. Visitors get to try some of the cellar beer, unfiltered and unpasteurised, served straight from the vat: most have to stand around and drink, but we were privileged to be allowed into an underground restroom lined with artefacts and photographs, where jugs of smooth, cool pilsen, perfectly conditioned, golden and slightly cloudy, were set upon the table, and we drank until we felt we had done enough to honour our hosts and the BHS.

The next day began with a trip to the Research Institute of Brewing and Malting in Prague, which has its roots in an organisation founded in 1873, the Society of the Brewing Industry in the Kingdom of Bohemia. The institute’s home is a building in Prague New Town called Brewing House – Pivovarský dům in Czech – and the ground floor is home to a microbrewery, bar and restaurant also called Pivovarský dům, started by former institute employees in 1998. This means that with the two sets of experimental brewing kit in the institute, and the microbrewery in the bar, the one building contains three separate breweries – four if you count the RIBM’s now disused old kit, lovingly polished up and on display next to a statue of František Ondřej Poupě, pioneering 18th century Czech brewer, who introduced the thermometer and the hydrometer (and who also wrote about bottom-fermentation yeast being used in Bohemia more than half a century before the invention of pilsen).

After a look at the tiny brewery squeezed into one corner of Pivovarský dům (including open fermenting vessels you can see from the bar), and a very Czech lunch in its dining room at (mmmm – dumplings! Dark lager!) we were away by metro train and bus to another microbrewery in a disused much larger establishment. Únětický Pivovar, in the village of Únětice, just six or seven miles from the centre of Prague was established in 1710 and shut down in 1949, after being nationalised. It reopened as a brewery (with new kit) and restaurant in 2011 and is now producing around 12,000hl a year. It is also probably the only brewery in the world to boast an indoor pétanque pitch, known as the Ubulodrom, from the name of the local pétanque club, United Balls of Únětice. (No, I don’t know why a Czech pétanque team has an English name.)

And then it was time for me to hurtle back to Prague and catch my return plane to Heathrow (the rest of Team BHS Bohemia were staying on). I had drunk excellent beer in a series of widely differing venues, and not scratched the surface of Czech beer culture: plenty of reason to make a return, which will definitely not take as many years to organise as the first trip did.

ADDENDUM: CZECH BREWING ICONOGRAPHY

The attentive traveller around Czech breweries cannot fail to notice the same iconography, with only unimportant variations, appearing repeatedly: almost identical symbols, for example carved into the lintel above the entrance to the cellars at Pilsner Urquell, on the beermats at U Fleků, in the brewhouse at Cernokostelecký pivovar and on the windows of Pivovarský dům.

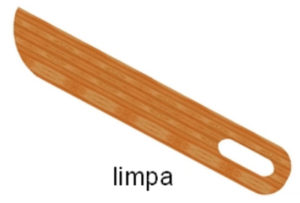

They are clearly related to the symbols many German brewers use as a badge in brewery trademarks and on bottle labels, the Malzschaufel (malt shovel), Maischegabel (mash fork), and Bierschöpfer (beer scoop). But the Czechs also include another tool, looking like a large wooden knife blade, with a slot for the hand at one end.

This, we were told by Martin Slabý, head of the technological department at the Prague brewing research institute, is the “limpa”, used in maltings to make furrows in the malt as it lies on the maltings floor. According to a thesis by Dagmar Chytková of Masaryk University in Brno on “Oldest Czech brewing terminology” from 2008, the limpa was a wooden tool used “který sloužil k shrnování kvasných pokrývek po kvašení ak přehazování sladu.” My Czech being non-existent, and Google Translate not being up to much, I have struggled with this, but it appears to mean that the limpa was used to sweep off excess yeast from the top of fermenting vessels at the end of fermentation, as well as smooth flat the malt in the maltings. Chytková says the origin of the word “limpa” is “unclear”, but points to “dolnolužický”, Lower Lusatian, which I believe is the Slavonic language known in English as Lower Sorbian (Lusatia, home of the Sorbs, is to the immediate north of Bohemia), where “limpa” means “čepel nože” – knife blade. That looks pretty clear to me.

Team BHS Bohemia struggled to think of an English word that adequately translated “limpa”, but I thought that a limpa looks rather like a strike, the tool used to smooth off malt when it is being measured in a bushel (hence the pub name Bushel and Strike) – and lo, in Z histore piva, a reprint of a book from 1900 on the history of brewing in Czech that I found while browsing one of Prague’s second-hand bookshops, is a picture of a limpa resting on what looks like the Bohemian equivalent of the bushel. So: for “limpa”, read “strike”.

Excellent work on the limpa research Martyn!

It’s staggering how much stuff you can uncover via the internet now.

An excellent article Martyn, which has whetted my appetite for a return visit to the Czech Republic. I have been there several times, and on each occasion seem to discover more really good beers, as well as places in which to enjoy them.

It sounds like Pilsner Urquell pulled out all the stops for your party; unlike the standard tour, which I did five years ago. Mind you, I had the VIP treatment back in 1984, when I visited the brewery as part of a trip organised by the short-lived CAMRA Travel. Back then, all fermentation and maturation took place in wooden vessels, and the cellars were used much more extensively than they are today.

A great visit and some good memories; apart from the food, which was stodgy, repetitive and uninspiring. Also, there weren’t hordes of tourists clogging up the streets.

I was on one of those Czech trips – there were actually two run back-to-back due to demand. I remember that we weren’t allowed to take any pictures inside the brewery, and that they had a scale model inside which we were told could actually be used for brewing – is that still there today? It would make a superb home brew kit for anyone with a large enough kitchen.

It was actually the first time that I ever went on a plane – landing on a snow covered runway at Praga made it an interesting experience. We were held up at immigration because tour leader Brian Glover had unwisely declared his occupation as ‘journalist’ on his visa form.