Beer made from immature “green” barley – who knew such a thing was possible? Or “red lager” made from actual red-coloured barley? And what does a beer taste like made with barley so controversial it caused a protest led by a marching band through the streets of Munich back in June?

If you’re one of the people who believes no beer writer should ever accept hospitality from a brewer, for fear of being corrupted, then you’ll need to stop reading this post now, because everything that follows was gathered on a trip to Copenhagen last week paid for by Carlsberg. I wasn’t on my own, of course: there were also a dozen or so beer writers and trade journos, and, more importantly from Carlsberg’s viewpoint, 250 or so assorted others including customers from key markets, staff from Carlsberg operations around the globe (I met some very nice men and women from Tuborg Turkey who insisted on having their pictures taken with me, having seen me in the film I was paid to appear in about last year’s Carlsberg ReBrew project, recreating an 1883 lager), people from PR and design companies who have Carlsberg as a client and mates of the Carlsberg Foundation (Carlsberg’s owner), all there to help celebrate 170 years since JC Jacobsen opened the Carlsberg brewery in the Copenhagen suburb of Valby.

For unknown reasons, this trip has encouraged a mountain of scorn and mockery from the rigidly puritan, obsessively put on public record every free pint anybody ever bought you end of the beer-writing world, with the top of that mountain of scorn claimed as the moral high ground. There are a host of reasons for believing this is a stupid and nonsensical position to take, but here are just three before we return to the important stuff. If you believe you have responsibilities to your readers as a writer about beer, you ought to take every opportunity to uncover information they will find interesting. If that includes accepting a free trip from a brewer, and you prefer to insist that your integrity will suffer unless you stay at home, you’re badly letting your readers down by refusing to go and learn stuff on their behalf. Next, if you accept payment in magazines or newspapers for your writings on beer, what do you think the ultimate source of that payment is? The advertising budgets of those brewers you refuse to accept direct hospitality from, of course.

Finally, does anyone think Michael Jackson paid for all his trips round the world to investigate breweries in dozens of different countries? Of course he didn’t: they were paid for by brewers, maltsters, distillers and the like, and those paid-for trips helped him become the massively influential beer (and whisky) writer he was. I have a book written by Michael, and translated into Polish and published by the Tyskie brewery in Poland, a subsidiary (at the time) of SAB Miller. If you had suggested to the Beer Hunter that by his accepting a commission from a multinational brewer to write a book his other work was irrecoverably compromised, he would have looked at you over his glasses with an expression that told you exactly what he thought you were. I’m not Michael Jackson, but I’ve learnt something useful on every trip any brewer has paid for me to go on, and that all feeds back into what I write.

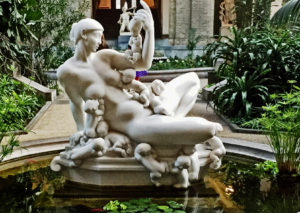

Back to Copenhagen. The highlight of the trip was supposed to be a TEDx event on the subject “Trust Uncertainty”, held for the 250-plus attendees in a hall at the deeply impressive Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, the art museum founded by JC Jacobsen’s son Carl, and paid for, of course, by the sale of many millions of pints of lager. (It has copies of Rodin’s Burghers of Calais and Degas’s Little Dancer of 14 years, and would be worth visiting just to stand in front of either one of those. You can see another copy of the Burghers outdoors in Victoria Tower Gardens, by the Thames in London, but for me the darkened, indoors setting of the Glyptotek greatly heightens the emotional impact of Rodin’s six stoic, heroic, literally monumental figures, depicted in the moments when they still believed they were about to be executed by the English, having chosen to sacrifice themselves to save their fellow citizens from being massacred.)

The TED talks were, I’m afraid, TEDious: what you need at these kind of events is at least one speaker with a little charisma. The finale was a speech by JC Jacobsen, founder of Carlsberg, who died 130 years ago, but appeared in front of the audience apparently resurrected and talking live (using what was described in the publicity as “holographic technology”, but which was actually the 155-year-old theatrical technique of Pepper’s Ghost). The talk by JC Jacobsen (ror rather, the actor playing Jacobsen) was, again, on “embracing uncertainty”. This was, as someone else (Pete Brown?) remarked, deeply ironic, since the real Jacobsen’s entire career, and also that of his great protégé Emil Christian Hansen, who pioneered pure yeast cell cultivation, was devoted to removing as much uncertainty as possible from beer brewing. But it was very much an internal PR event for Carlsberg, as these shows generally are: it was being streamed live so more than 4,000 company employees around the world could tune in.

The “break-out session” at the end, however, was much greater fun, since our group was taken off to the Carlsberg research laboratories for a presentation by Erik Lund, head brewer at the labs, and Zoran Gojkovic, the director of brewing science and technology, on three pioneering beers. The tall, thin, ascetic and slightly starchy Dane and the rounder, jollier, goatee-bearded Serbian make a great double act, powered by the huge enthusiasm they both obviously have for their jobs.

The first beer they gave us was made from what Carlsberg is calling its “fourth generation barley”, a variety grown in New Zealand that has had the lipids that give papery, cardboardy flavours when a beer gets stale, the polyphenols that give rise to haze in beer, and the compounds that end up as dimethyl sulphide, DMS, which gives an unwanted “sweetcorn” taste to beer, bred out. The result, said Zoran, is ” a very, very stable beer, it’s a very clear beer, you don’t have to stabilise it at all, because there is no haze development as happens with a normal barley.” According to Erik, “if you kept this beer in your home for six to nine months you would hopefully find it will stay fresh longer.” The other advantages, from the brewers’ viewpoint, is that they can use less energy in malting and wort boiling to educe DMS, they don’t have to “lager” the beer to wait for any DMS flavour to disappear and the beer to clear, and they don’t have to filter it or chill it to just above its freezing point and add clarifiers remove either the protein fraction or the polyphenol fraction which cause haze in beer, because the haze-causing polyphenols are not there. This, of course, saves energy, money and time.

The problem for Carlsberg is that its attempt to apply for patents surrounding the development of this new barley have been greeted with much angry protesting from organisations such as Greenpeace and No Patents on Seeds, who claim the patents the company has been granted are illegal under EU law. Carlsberg, for its part, says the patents were not for the barley but for the technique used in its development. It’s a slightly uncomfortable row for the company whose founder specifically refused to patent the crucially important techniques for pure yeast cultivation his laboratory worked out in the 1880s, and instead gave the secrets away to anyone who asked. But just because you didn’t patent one technique 130 years ago, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to protect your investment in much later research. Nice-tasting beer, anyway, whatever side you take on the controversy, unpasteurised, fermented with a newly developed Carlsberg lager yeast at 16ºc, lightly hopped to 17 BU, and then slightly dry-hoppwd with Nelson Sauvin, straw-coloured, and 5 per cent abv.

The next beer up was almost certainly unique, and we were the first people outside the Carlsberg labs to try it: lager made from green, unripened barley. This project started, according to Erik, “after we were asked, ‘Could you make a beer in Greenland?’ It’s nicely cold already, you wouldn’t have to expend so much energy in cooling the lager, and that would be good, and we said, ‘Yes, of course we could do it.’ Then we were asked, ‘But could you grow barley?’ Yes, you can grow barley in Greenland, but there’s no time for it to mature. But what will happen if you take a really immature, fresh barley grain? No one will make wine or cider from unripe fruits, because sugar only appears when fruit matures, it comes at the end of maturation,. But with barley, with cereals, it’s different. You start with the free sugars and then they get integrated into starch, which you then have to break to release sugars for the fermentation.”

So on June 20 this year, Erik went to the island of Funen, in the middle of Denmark, and under the full, hot sun he harvested unripe barley, six weeks ahead of normal harvesting time, with an old-fashioned hand sickle borrowed from the barley labs at Carlsberg – getting a sunburnt neck in the process. Back at the labs in Copenhagen the green young barley was frozen, and then later juiced, stalks and all, and a beer brewed with it on the pilot plant at the labs, with a ratio of 30 per cent green immature barley and 70 per cent standard malt. “We had to start somewhere and this is our first try,” Erik told us. “I didn’t know if it was going to be too much or too little. I was a little bit afraid about how much contribution we would get from the green barley, but we had quite a nice conversion. In future we could certainly go to 50 per cent green barley We could not use this 100 per cent, that would be difficult – I don’t think you would like it, and I would have to use conversion enzymes, because there’s nothing in the green barley.”

The juiced green barley was added at the lauter tun stage, rather than in the mash tun – “we are using everything here, including parts of the stalk, it would completely block our small pipes, which are the size of my thumb. In a big brewery it would work to add it to the mash tun,” Erik said. The final beer was a 5.5 per cent abv brew with a slight greenish tinge to the foam from the green barley, and a distinct aroma, to me, of green pea pods when first poured, though that soon vanished. According to Zoran, ” The idea behind it is that if you are harvesting young barley you may capture some interesting aromas and nutrients. We actually didn’t know until this morning how the final taste of the beer was going to be. This is the risk we took: ‘It’s a crazy idea, will it really work?’ – you tell me. You get a green, grassy freshness – it’s an off flavour in lots of beers, but there’s an additional part which is very nice. Sweetness is there, but these are not free sugars. We haven’t analysed yet the sugar composition of this beer, but the sweetness is probably coming from longer sugars that the yeast cannot ferment.”

Developing a “green barley beer”, Erik said, “offers the possibility of growing barley that can be used for making beer in parts of the world where it would be too cold to grow barley that would fully ripen, Maybe you could grow barley in Greenland and have a beer still – maybe you could grow barley first and have some other crops, or maybe in some places you could have two harvests in one year.”

The last beer was also, very probably, unique, and again we were the first people to try it, fresh out of the fermenter. Erik told us: “We were thinking, ‘Why is all barley being used the traditional kind? It gets malted into different colours, so you get dark beer to pale lagers, and you also have out there red ales, but they are all brewed with standard barley, being altered to some degree in order to get a reddish or darkish colour. We said, ‘Could you make a really red beer?’, and we were able to find in the seed bank a variety of red barley, which we cross-bred with a modern malting barley and propagated. There is no artificial colouring, no raspberries or other fruit in this beer, it’s red because it’s made from red barley.

The barley is red, Zoran added, “because it’s the way the plant protects itself from stress. You go to the beach, you get a nice tan, it’s the same mechanism, to protect yourself, but a different pigment. In the red barley it’s a complex mixture of anthocyanins, a little bit similar to red rice: extremely high in antioxidants, so probably the healthiest stuff you’ve drunk today. [Note for scientific cynics: there is no evidence consuming anthocyanins, which certainly act as antioxidents for plants, has a beneficial effect on human health.] The genetics of the colour is complex, but it’s easy to use classical plant breeding methods, because you can see the colour in the offspring, you can see which plant is red, which one is not. The red barley was originally from Asia, but our barley group spent a lot of time to breed a nice taste in, because these are originally wild plants, so we now have a lot of Carlsberg barley genes in there while keeping the colour.

“Your brain tricks you, because when you see this nice red colour your brain sends signals that say, ‘This must be some nice red fruits, this must be strawberries, raspberries, cherries’. But no, there is nothing like that in there.”

Brewing with the red barley, a huskless variety, again grown in New Zealand, was tricky: “Basically it’s the outer layer that is red, and when we tried to malt it, adding water to steep the kernels, we lost all the colour in the steeping water, even though we were very, very careful,” Erik said. “So we had to skip trying to use red malt, because we couldn’t produce it. In this beer, therefore, we have used a high proportion of unmalted barley, because we wanted to get as much red colour into the beer as possible. We used 45 per cent of this red barley and a standard malt for the remaining 55 per cent, then basically a normal mashing and brewing procedure, pretty gentle, not too long mashing, not too long a boil, in order to not exhaust the red colour too much.

The beer was hopped with Mosaic and Citra hops, and came out with an abv of 5.2 per cent, an EBU of around 13 and a relatively low attenuation of around 65 per cent, meaning a fuller, sweeter beer. Even so, to me there was an astringent dryness present I would put down to the anthocyanins that give the barley, and the beer, its red colour – the same sort of anthocyanins that make blood oranges so tart. It was also an extremely attractive-looking beer, a beautiful glowing crimson, with a great head. “We haven’t done a full analysis of the red barley beer yet, but the foam is remarkably stable, we did measure that, and we got a value for foam stability which I have never in my 25 years in brewing known,” Erik said. “We talk about a value of, say, 110, the seconds it takes the foam to collapse to half its volume, if you have a figure of 130 or 140 you’re into gold medal territory, and with this beer it was 170. I’ve never seen anything like it. We also saw during fermentation, the foam simply rose out of the fermentation tanks – maybe the yeast was so amused about the colour, I don’t know. I think it’s because of this enormously stable foam.

“Do we want to produce a red beer? I don’t know – at this point it was just to show the diversity within barley and what we are able to do. We can grow this barley in Denmark, but it’s not as red as that grown in New Zealand, because it’s the sun that encourages the colour.”

And on that, and after a brief discussion on why modern yeast strains, which produce much less diacetyl and sulphur compounds, make the 90-day lagering still practised by some Czech brewers unnecessary, we said goodbye to the Carlsberg labs. We’ll zoom past the dinner in the evening for 250 at JC Jacobsen’s old home, which was interesting – every ingredient had to be something that could be found in beer, so the only meat was oysters, as in oyster stout (clearly Carlsberg’s chefs had never heard of Mercer’s Meat Stout, which would have allowed them to use beef extract) and the main course featured black barley cooked risotto-style – but not, I think, worth deeper analysis. Instead let’s talk about another good reason for accepting invitations from brewers: it enables you to go off on your own after the “jolly” is over and do things you could never afford to do otherwise. The day after the TEDx talk I went out to Koelschip, the specialist Belgian “aged beer” bar next door to, and part of, Mikkeller & Friends in the suburb of Nørrebro, which is run by Dennis Vansant, another old “Facebook friend” I had never actually met.

Dennis, who moved from Belgium to run the bar, is one of the most knowledgeable people you will find on lambics, geuze (to use the Dutch spelling) and the like, the bar is filled with rare and unusual beers, many expensive (this being Denmark, where a round of four 40cl beers in a craft beer bar will see you hit for £25 – nearly £9 a pint), a few dear enough – over £100 a bottle – to give the twitterati blackouts, and I had a tremendous evening chatting to him about beer, beer and food, beer cocktails and the rest. Mikkeller & Friends/Koelschip is a fair trip out of central Copenhagen, but if you go to one bar in the city, I’d say make it this one.

I know a couple of homebrewers who tried to make a red beer from anthocyanin-rich red rice (as a high percentage adjunct); but they found the red pigment coalesced with the hot break and was left behind after the boil. I wonder if there is variation in anthocyanins which may cause some to bond with protein and some not.