It’s a beer fact guaranteed to make British drinkers boggle in disbelief: one of the biggest selling beer styles among black working-class South African men is milk stout

While milk stout has seen a tiny renaissance in the UK, with craft beer brewers producing examples of the style, it is still mostly thought of, if it is though of at all, as the beer drunk by little old ladies sitting in the saloon bar on their own. The last person in Britain to be known for drinking milk stout was Ena Sharples, sour-faced harridan of the soap opera Coronation Street, who disappeared from television screens almost 40 years ago.

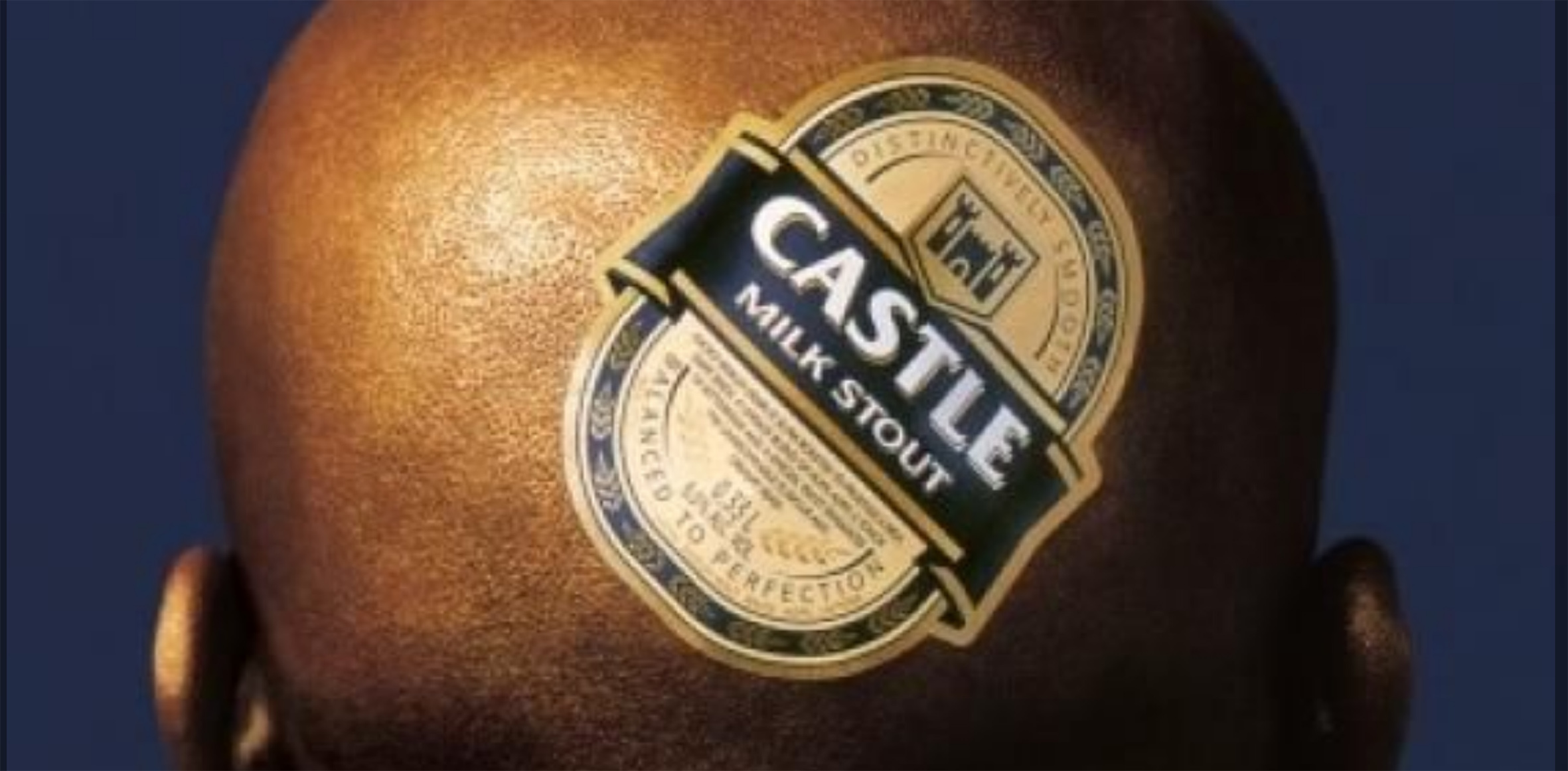

In South Africa, however, milk stout has a totally different image: Castle Milk Stout, originally a South African Breweries brand and now, since it acquired SAB, owned by AB InBev, is a long-time favourite of black workers, and is now being marketed at the country’s black middle class as the beer to drink to show you haven’t lost touch with your roots. (Great ad, that – possibly one of the best beer ads ever.)

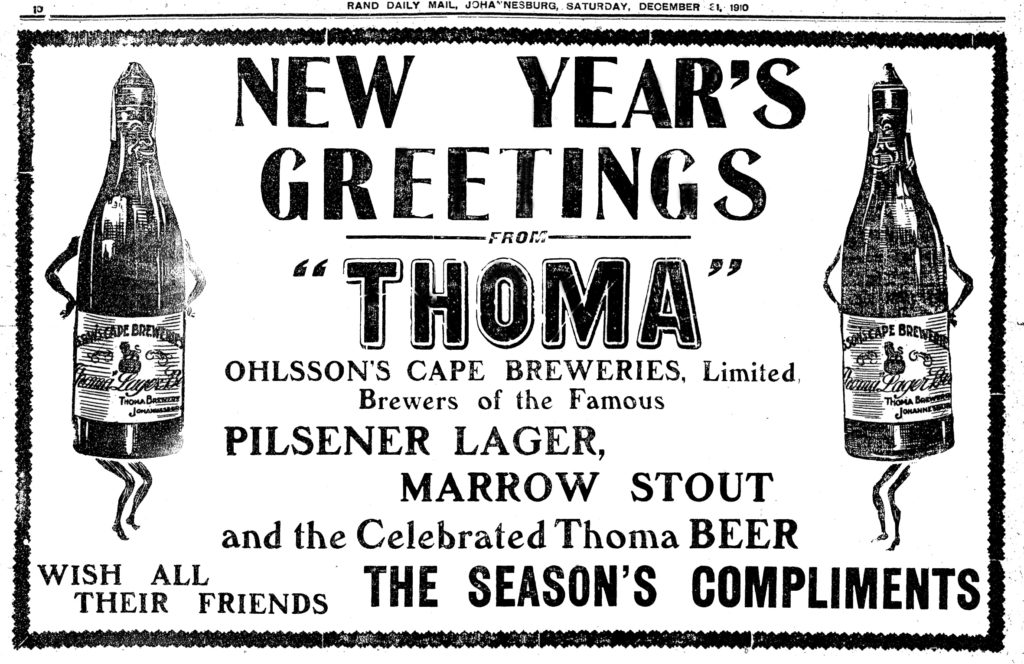

Stout and porter had been popular in South Africa from the earliest days of British colonisation, but by the start of the 20th century lager was starting to take over. However, variants on stout were appearing in South Africa, such as oatmeal stout, which was made by several firms, including South African Breweries, which advertised its Castle oatmeal stout in 1916 as providing “health and strength for tired people,” and Chandler’s Crown brewery in Ophirton, Johannesburg, which was still advising customers in 1932 to “Drink Chandler’s Oatmeal Stout and keep colds away!” There was also the peculiar-sounding and short-lived Marrow Stout (bone marrow or vegetable marrow, it is not clear which) brewed by the Thoma (sic) brewery in Johannesburg (founded in 1892 by a German, August Thoma, in Braamfontein, Johannesburg and taken over by Ohlsson’s Cape Breweries in 1902), which was first advertised in the Rand Daily Mail in 1909 but does not appear again after 1910.

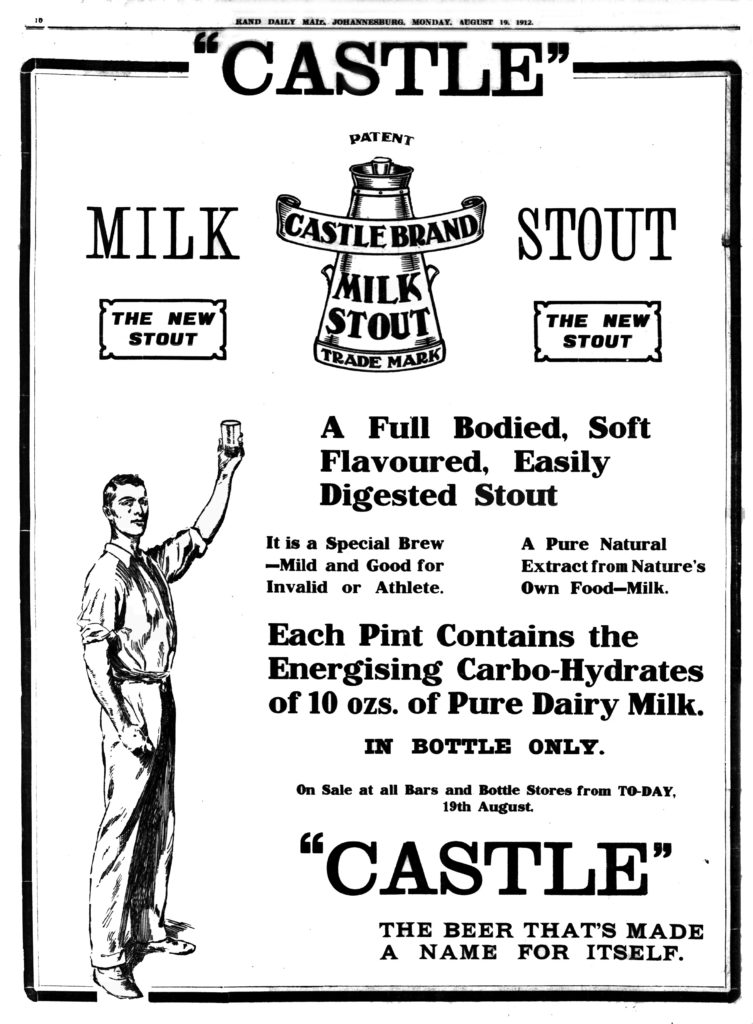

However, just as “marrow stout” was disappearing, a new style of stout appeared that would turn South Africa into one of the biggest stout-drinking countries in the world. Sweet stout had been growing increasingly popular, but as the beer aged it lost its sweetness. The idea of brewing stout with a dose of unfermentable lactose sugar, derived from milk, to keep it staying sweet, had been first patented by William Melhuish, a food chemist from Poole, Dorset, in 1908, and the first “milk stout” was brewed by the English brewer Mackeson’s of Hythe, in Kent, in 1909. Mackeson licensed other brewers to make their own milk stouts, and the Castle brewery launched its version in August 1912 with a full-page advertisement in the Rand Daily Mail. Castle Milk Stout became one of the company’s biggest selling beers, particularly after a ban on black South Africans drinking “European” beers, imposed in 1928, was lifted in 1962.

The appeal of the six per cent abv drink to black South Africans, according to the South African advertising guru Happy Ntshingila, was that the traditional sorghum beer which was all they were legally allowed to drink during those years has always been regarded as a food as well as an alcoholic drink, and the “milk” part of milk stout gave it the same image. By the 1990s milk stout in South Africa was primarily a drink of blue-collar Nguni men – members of the Zulu, Xhosa, Ndebele and other South African peoples. The beer was frequently sold in quart bottles, for sharing, the way a calabash of sorghum beer would be shared, and was described as “the most physically masculine brand in the SAB stable.” It was about as far from the image that milk stout drinkers had in the beer’s country of origin – elderly ladies sipping a half-pint in the pub on their own—as it was possible to travel.

The large market for milk stout in South Africa did not go unnoticed in Chiswell Street, the London headquarters of Whitbread, the company that had acquired Mackeson in 1929. However, when the British brewer launched the Mackeson brand in South Africa in 1967, it was as Mackeson Porter, not Mackeson Milk Stout. This, the first launch of a beer under the name “porter” by a British brewer since, probably, the 19th century, was most likely because South African Breweries had a local trade mark monopoly on the use of the expression “milk stout”: there had been other milk stouts in South Africa besides the one from Castle, including Ohlsson’s Lion “melk stout”, as it was branded in Afrikaans, which was still being sold in 1952, but SAB had acquired Ohlsson’s in 1954. (In the UK the term “milk stout” had been voluntarily abandoned by brewers for fear that legislation would be introduced to ban it anyway.) Mackeson Porter was on sale in South Africa until 1972 before disappearing, unable, without the world “milk stout” on the label, to make any impact on a market that had not seen a beer called “porter” for generations.

Early in the 1990s, after the government of South Africa unbanned the African National Congress, and with black Africans increasingly drinking lager rather than milk stout, South African Breweries gave the advertising brief for Castle Milk Stout to the country’s first all-black ad agency, HerdBuoys. A series of advertisements that successfully combined images of black urban success with rural tradition—and milk stout drinking—sent sales soaring again, to 100,000 hectolitres (84,000 US barrels) a year. By 2003, Castle Milk Stout was the fourth biggest liquor brand in South Africa, and the second biggest stout brand in the world. Its production still included roast malt added in the mash tun, unlike Guinness, which had long gone over to using an extract of roasted barley, added post-mash, and other tweaks peculiar to making Castle Milk Stout, including adding caramel alongside the lactose, crash-cooling the fermentation to encourage the yeast to produce stop the yeast mopping up diacetyl, which increases the “butterscotch” flavours in the beer, and a lager-like maturation at -2ºC.

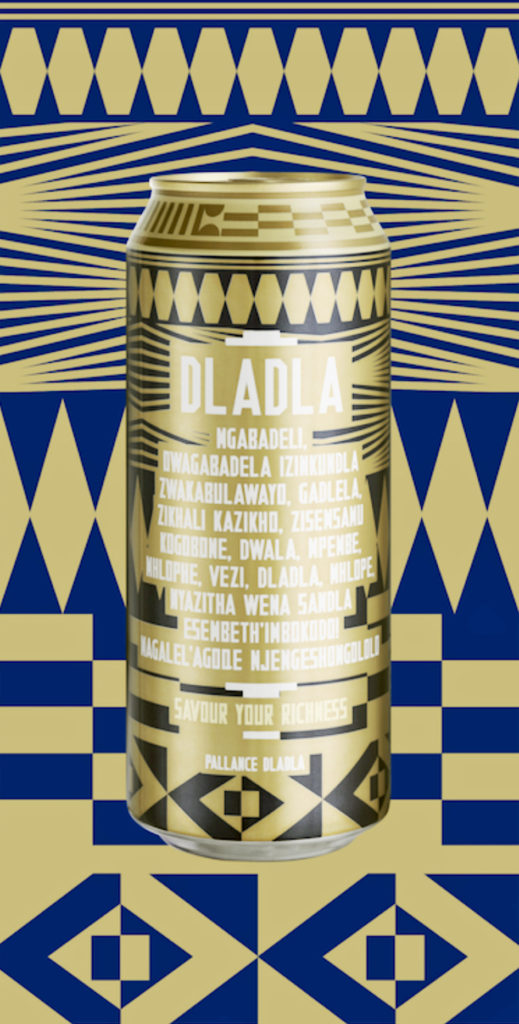

By 2011 Castle Milk Stout was available in a nitrogenated draft version, though it is still most often found in 75cl bottles and in cans. However, in the winter of 2014 SAB introduced “ultra-smooth” milk stout in a nitrogenated can, and also a limited-edition “chocolate-infused” 4.5 per cent abv version of Castle Milk Stout, which came back as a regular variant the following year, again available in 75cl bottles. This, together with “repositioning” the brand as a “premium” product, and whites picking up on the brand as the growth of craft beer made them more aware of “unusual” beer styles, helped push sales up 14 per cent year-on-year. It has still been maintaining its “traditional” image in South Africa, however, with promotions that included printing tribal clan names, and clan praise songs, on the cans. The brand has also moved abroad, capturing market share from Guinness in Nigeria, where stout makes up 14 per cent of the beer market, and also being brewed in Tanzania, Ghana, Uganda and even South Korea.

It’s a long way from Ena Sharples.

Great article as usual. I live in Barbados and we have a very limited range of lager beers available – but we do have Mackeson Triple Stout (with milk stout also written on the label) brewed in Trinidad and Tobago by Carib Brewery. There’s also a locally brewed Guinness and a Jamaican brewed Dragon Stout which is sweet and stronger than the Mack.

[…] Cornell has written a fascinating piece about the survival of milk stout in South Africa where its image is very different to the one it has, or had, in the […]

I visited South Africa a few years ago and I was pleasantly surprised to find that a stout was so widespread nationwide. Nice to read its background here.

Another stout that is popular in a former colony is Suriname’s Trio Stout, which is still imported from Holland (sorry, haven’t found the time to translate this article into English yet)

http://verlorenbieren.nl/het-trio-stout-mysterie-2/

Absolutely fascinating, Roel

Just to add a bit of technical nerdery, crash cooling doesn’t encourage diacetyl formation. It slows down the rate at which yeast will break down the diacetyl that has already been produced during active yeast growth.

Thank you very much – corrected

Great post Martyn. One point of interest is that Castle Milk Stout is actually fermented with a lager yeast, with attenuation arrested to leave some body.

Great article. I have been drinking Castle Milk Stout since the early eighties. Back then it had a much stronger burnt taste which was for me quite addictive. Currently the taste is a lot smoother. The chocolate version was first brewed at the SAB training centre and served at various beerfests around the country where it was called Willy Wonka. Due to it being very popular they distributed a limited amount to bottle stores around Johannesburg. It must be selling well as it’s still available.

[…] * Thanks to Martyn Cornell for […]

Interesting article thanks. I worked for SAB at their Isando brewery (near Johannesburg) in the sixties and well remember when Whitbread opened their competitive brewery in Alberton. Their main product was a lager to compete with Castle, supported by their “Final Selection Ale” (Burton style) and the “Mackeson Porter” you discuss. The beers were all good, but never captured significant market share. SAB also brewed a “Glucose Stout” in addition to the milk stout. We also brewed Guinness under licence; it was very popular with the black population, thanks to the slogan, “A baby in every bottle!” I once, on night shift, caught one of the workers quenching his thirst by dipping his hard hat into a Guinness fermenter. Couldn’t happen these days with the new designs.

Now in retirement in Western Australia I make Imperial Stout in winter with my “Grainfather’ set-up. Occasionally I can still buy a Castle Milk Stout at the Kalahari South African winkel.

Thank you very much for that, Ian, absolutely fascinating, I wasn’t aware that Whitbread had actually opened a brewery in SA. And I love the story of the guy drinking Guinness out of his hard hat …

Good to hear from you Martyn. My wife and I recently enjoyed a short bus tour of England and Ireland. It is always a pleasure to try a few of your wonderful local brews. In Dublin the tour guide asked the group which country in the world drank the most Guinness per capita. How did this ex South African, now Aussie, know it was Nigeria? When we brewed Guinness in Johannesburg in the sixties, the secret Dublin brewed ingredient called “mature beer”, which was added in small amounts to the local fermented beer, would arrive in a steel vessel that looked a bit like a small submarine hull. When opened, the aroma was quite overpowering and wags at the brewery reckoned the local vultures would cruise past to investigate.

[…] relationship with milk stout, documented by UK beer writer and historian Martyn Cornell on his excellent Zythophile blog. It’s not a beer style that retains much popularity elsewhere, and yet of all the styles to […]