I am green – viridian. Ron Pattinson has been dropping hints every time I see him about his secret big new project with Goose Island in Chicago, and it’s now been revealed: a reproduction of a London porter from 1840, including authentic heritage barley, properly “blown” brown malt, and blending a long-vatted beer with a much younger version. Who do I have to kill to get hold of a bottle?

Of course, some people have knee-jerked in and slapped this down because it involves the Evil Empire, AB InBev, owner of Goose Island and, in the opinion of many, too many other formerly small craft breweries, from Four Peaks to Wicked Weed. The PC line is “I’ll never drink anything produced by a company that is fundamentally bad for, and opposed to, small independent operators and their survival.”

Of course, some people have knee-jerked in and slapped this down because it involves the Evil Empire, AB InBev, owner of Goose Island and, in the opinion of many, too many other formerly small craft breweries, from Four Peaks to Wicked Weed. The PC line is “I’ll never drink anything produced by a company that is fundamentally bad for, and opposed to, small independent operators and their survival.”

As it happens, I’ve just finished reading Barrel-Aged Stout and Selling Out Josh Noel’s deservedly award-winning book from last year on the take-over of Goose Island by Anheuser-Busch – do try to get hold of a copy, it’s an excellent, even-handed and sympathetic analysis of what happened and why it happened. You’ll certainly put it down after 345 pages and conclude that AB InBev is indeed interested in nothing more, ultimately, than getting you to buy its product in preference to anybody else’s, and if that meant using its weight, wealth and power to crush the entire global craft beer scene, it wouldn’t care. But that’s what big corporations do: criticising them for wanting to dominate the world is like criticising lions for chasing down and killing wildebeest. It’s the nature of the animal. Run faster, wildebeest.

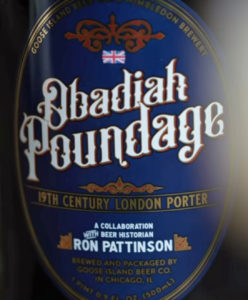

And if AB InBev wants to spend silly sums of money flying my mate Ron, and Derek Prentice, former brewer with Truman’s of Brick Lane, then Young’s, then Fuller’s, and now Wimbledon, out to Chicago to advise on recreating an almost 180-year-old beer, and take enormous pains getting the ingredients and the methodology just right, in the hope that this will greenwash their corporation and get people like me to write admiringly about them, rather than attack them for trying to squeeze smaller rivals out of the market, then they’re partly correct: I’ll still criticise where necessary, but I’m also writing admiringly about the Obadiah Poundage porter project, because I think it’s wonderful to be able to drink this beer from the past, and I don’t believe very many other organisations would have the big wallet, or the commitment, to undertake such a recreation. This is an expensive beer made with unusual ingredients back in March last year, which was then left sitting around occupying valuable real estate in Chicago for a year before being blended with the newer version and put on sale. Most companies’ accountants would have been screaming themselves puce. If not AB InBev, who else would undertake such a journey?

Anyway, watch this fascinating 20-minute video about the project, listen to Mike Siegel, research and development boss at Goose Island explain it all, see if you can spot John Hall, founder of Goose Island, popping into shot uncredited occasionally, and then come back here and I’ll discuss a few interesting points that arise, so pay attention and listen out in particular for the mentions of hornbeam, there will be questions afterwards.

I didn’t expect to find anything to criticise about the history when I watched that. I nodded along as Derek Prentice accurately recounted the role of porters in 18th century London, and as Ron described the change from the all-brown-malt porters of the early 18th century to the more complicated grain bills of later porters, with pale malt, “patent” black malt and “blown” malt dried and browned over faggots of hornbeam wood, and I sat awed as Andrea Stanley of Valley Malt in Massachusetts showed the making of just such a batch of “blown” malt over a fire of hornbeam. And then something strange happened. My subconscious popped up and said: “Hornbeam – are you actually certain about that?” So I checked.

For the past 18 months I’ve been writing what is meant to be the definitive history of porter and stout, and I’ve read several hundred books and articles to pull that together. All that information goes down into the subconscious, where, as is the way of the human brain, new connections are formed that the conscious mind is unaware of until something bubbles up from the id. Now, “maltsters made blown malt for porter by drying the grains over blazing hornbeam” is a solid received fact among historians of brewing. I never doubted it. Hough, Briggs and Stevens’s Malting and Brewing Science from 1971 says so: “dried in a fierce heat from a fire of hardwood faggots made from oak, hornbeam, ash or beech” (p166). Steeped in Tradition, a history of the malting industry from 1983 by Jonathan Brown says so: “These kilns were fired by wood, mostly and preferably oak, but beech, hornbeam and ash were also commonly used.” It makes sense: blown malt was a speciality of the maltsters of Ware and other towns in East Hertfordshire, and hornbeam, which burns with a bright, hot flame, is abundant in the woods of East Herts.

But as my subconscious prompted me into confirming, if you go and look, you will not actually find any references to hornbeam being used by maltsters during the time that blown malt was still being made. Many authors do not specify any particular wood. Of those that do, William Black in his Practical Treatise on Brewing of 1844 says blown malt is heated with “faggots of dry, hard wood, commonly beech or birch; fir imparting a tarry taste.” (p26). Henry Stopes, who was the 19th century’s Mr Malt, spoke only of billet and faggot wood “generally of oak but occasionally of beech” in making the blown variety (Malt and Malting, 1885, p159). E.R. Southby’s Systemic Handbook of Practical Brewing from the same year says blown malt is “dried rapidly over a fire of beech or birch wood” (p215). Herbert Edwards Wright’s A Handy Book for Brewers from 1892 says blown malt is made by subjecting the barley to “a sudden blast of intense heat generated by heating up the kiln fire with oak or beechen faggots or billets” (p309). (Wright also says that the fire risk “and the high rates of insurance demanded in consequence” meant this was a variety of malt generally made only by specialists.)

So, what to say to Ron, Derek, Andrea and Mike: “Er, thanks for all the trouble you went to, guys, that was amazing, especially the hornbeam, but, um, you might have been better off with beech …” I’m not saying nobody ever used hornbeam to make blown malt: I think it’s very likely they did. It was available, in the right place, and has similar characteristics to both birch (which is in the same botanical family) and beech, which we DO known were used (indeed, the hornbeam is known in some parts of Britain as the “ay beech”, for its habit of keeping its leaves through winter, that is “for aye”.)

Best not to say anything to dampen the party, really. And let’s not mention that the American hornbeam that Andrea used is a slightly different species to English hornbeam: that would be taking my (deserved) reputation for picky pedanticism too far down the road. Nor let us question why an 1840 porter is named for a man who probably died at least 70 years earlier, the pseudonymous commentator whose letter to the London Chronicle in 1760 about the tax on beer provides historians with so much information about the history of porter. (Someone in the film wonders where the original “Obadiah Poundage” got his name from: “Poundage” is an old word for tax, and one of the many Obadiahs in the Old Testament was a porter “keeping the ward ” [Nehemiah 12:25].) And please, let’s not ask why you have to query every single damned received historical fact because too often what you thought was indisputably true isn’t indisputably true at all. No, there’s a much more important question than all that: where’s my bottle?

Fair enough, save, don’t forget alder as an option, which is documented for a porter-like beer early in the 1800s or at least it’s an irresistible inference.

http://www.beeretseq.com/from-oak-and-alder-to-porter/

This alder has a North American relation too, again not quite identical to the British variety, but close enough surely.

Any of these hardwoods, or a mix as the term Oak and Alder suggests, would work too. Alder, which is rather slow-burning, is ideal to pair with oak in fact, which burns bright and hard when dry.

I think I got it from this:

“The kiln was fired by Faggots and poles. Faggots are brushwood about 3 feet long and were held together by a forked branch at the base. The brushwood was held in place by a “tyer” of strong string. The wood was always hornbeam. The poles were again hornbeam with a thickness of about3 inches and again about 3 to 4 feet long. The idea was to start the fire with faggots until colour was gained by the malt itself (using last year’s drier crop). At this point the malt was turned off the kiln. A very hot job. It was not surprising that 2 gallons of beer were drunk before breakfast!!

The process was very dangerous from a fire point of view and many brown malt kilns were burnt down. Our own in Stanstead Abbots were brought to the ground in 1902.

A modern equivalent of Brown Malt is produced in a roasting cylinder, but lacks the smoky flavour of the true material.

Production ceased in about 1957, when many smaller maltsters were being taken over, and with the very small amount being needed in modern brewing, it no longer became economic, particularly with the huge insurance premium being charged.”

“The Production of Brown Malt”, Guy Horlock , 2002/2009 (Curator, French & Jupps Museum, Stanstead Abbotts, Hertfordshire

Thanks for that reminder, Ron – I’m about as sure as I can be without actual written evidence from the time that Hertfordshire maltsters would have used hornbeam to make brown malt, and what you and Goose Island did was indeed historically accurate, but it’s just curious that for whatever reason no 19th century writer mentions it, only oak, birch and beech.

The case for alder, textually and inferentially, is strong even though no one says in plain words it was used to kiln brown malt. Yet hornbeam can hardly stand on a different basis for the nub of it if later writers mentioned it, it must have been handed down. There are probably too European precedents, Norway or similar.

The aspect of mixing should not be overlooked as some woods are hard to start a fire with on their own, oak say. Softer grain and harder are often mixed for this purpose and this is why oak and alder may have been mixed woods for a kiln. Other combinations were surely used. Perhaps beech is the juste moyen, I don’t know.

I doubt hornbeam was used on its own very often just as alder likely wasn’t, for opposite reasons, but each of these has to be viewed as traditional, alone or in any combination.

Could it be that hornbeam was regarded by maltsters as a type of beech at the time, and thus not separately mentioned?

Quite possibly, yes …

So. Pickiness aside, you’d maybe like a bottle? I know you only hint at it, but I get that impression. (-:

Oh no, was I really making people think that?

Never having had such an historical porter, how would you describe the level and flavor of the smokiness? We’ve worked with blazing hot rocks before to make Stienbier so we would love to try and brew a “blown” malt beer as well, as we have no aversion to drinking pints or even gallons of beer before noon on a brew day. Cheers.

The smokiness is pretty subtle. Nothing like as in your face as Schlenkerla.

Here’s an extensive article from this morning’s Chicago Tribune with a tantalizing description of the taste.

“In the aroma and on the palate, Obadiah Poundage is at various points darkly fruity, smoky, leathery and tart, all underscored by the familiar roast character expected in a porter.”

I’m considering a quick trip over to Chicago. We have good train service from Ann Arbor, Michigan. About four hours.

https://www.chicagotribune.com/dining/ct-food-obadiah-poundage-goose-island-historical-porter-0501-story.html

Jeff,

come along on Monday. The beer is wonderful. So complex and not like any modern Porter.

Wow, really nice! This whole project was passing under my radar all this time. I was planning to bree something along those lines next summer in collaboration with a small malster from Quebec, too late! Will do it anyway! As we are only a brewpub we don’t attract so much attention anyway. People don’t seem to understand what you can achieve with good and solid big brewery, good fully trained staff and lots of money. It can be..meh.. as the major breweries can be.. But they have everything to make the best beers in the world. Can’t wait to taste it.

With regards to the effect of the different wood on the flavour of the malt – how come by mid 19th century all malts weren’t being kilned in an indirect-fired kiln? Why were malsters still producing malt that was effected by the fuel? Cost?