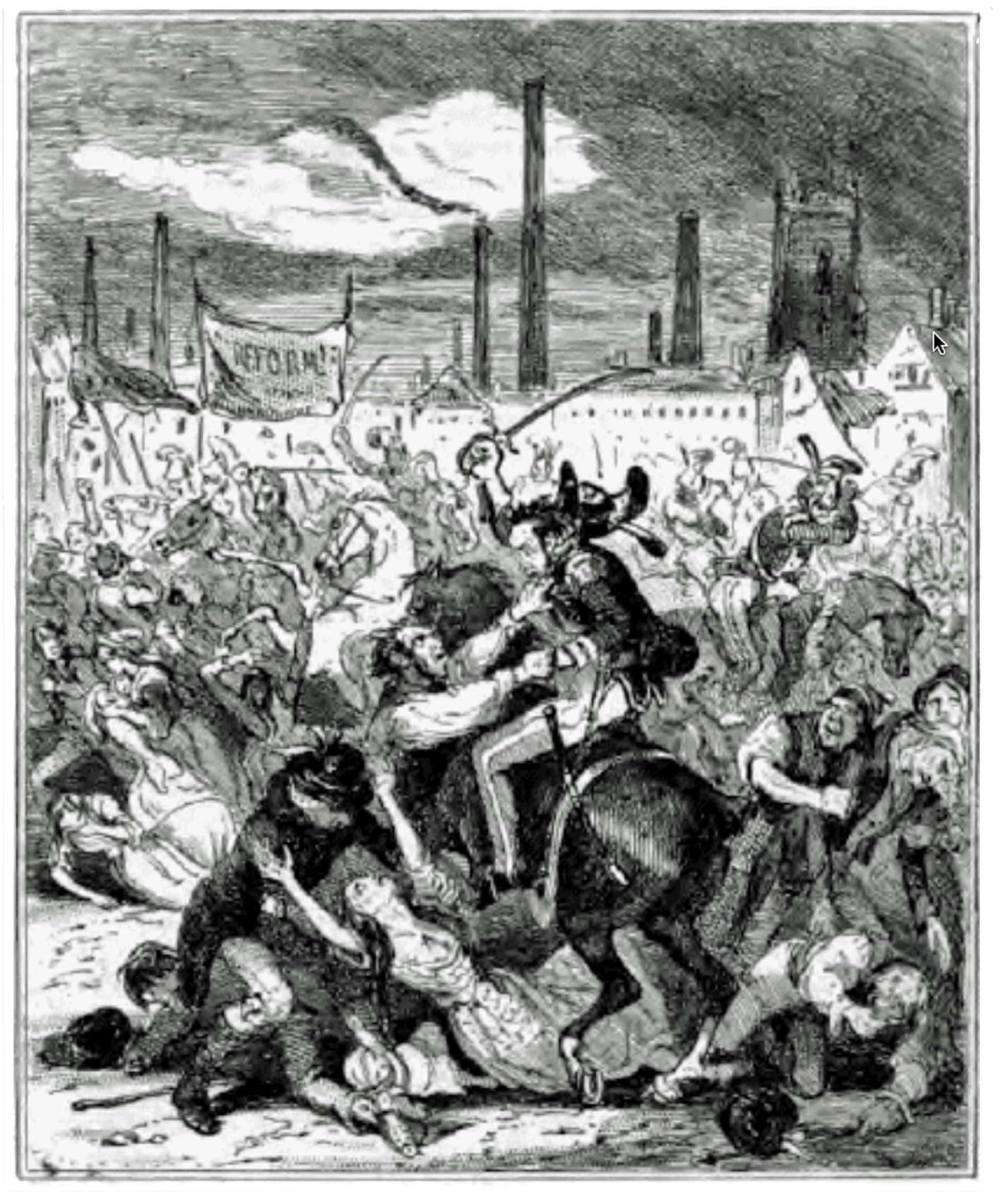

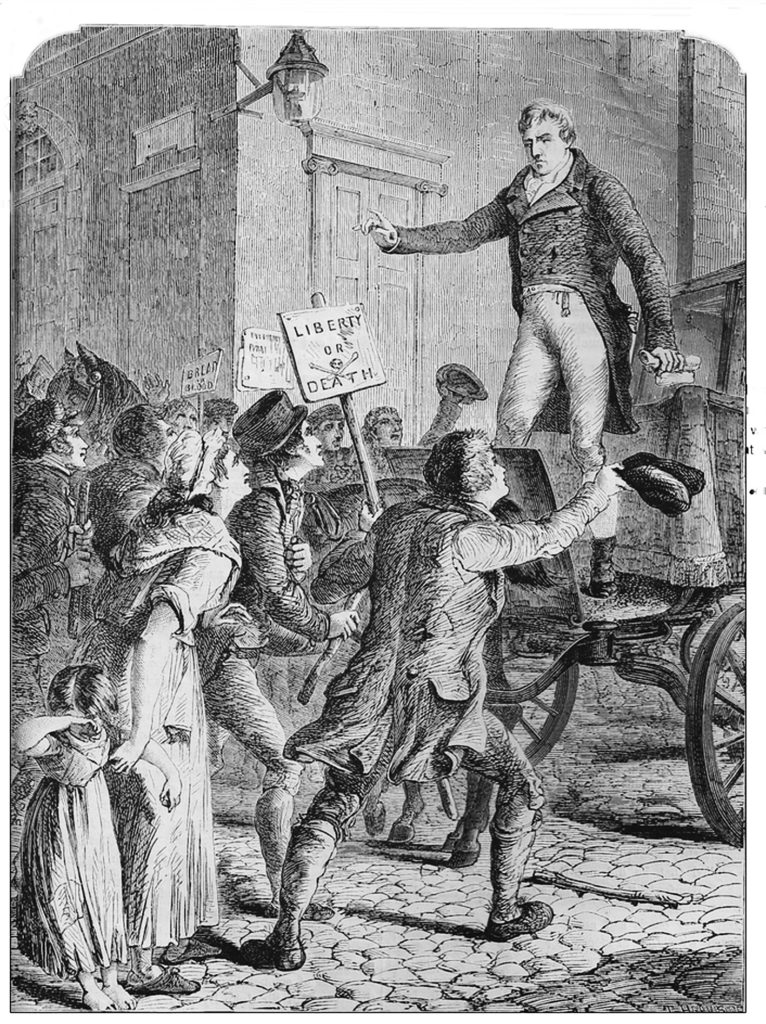

The 200th anniversary next year of the “Peterloo Massacre”, the assault by mounted troops on a crowd gathered in Manchester to hear speeches in favour of parliamentary reform, has been marked by the release of a film by Mike Leigh starring Rory Kinnear as Henry “Orator” Hunt, the main speaker at the meeting in St Peter’s Field, whose arrest by the authorities sparked the events that led to at least 15 people being killed. Rory thus joins the short list of people, including Bob Hoskins, who can be the answer to the question: “Which actor has played a brewer on screen?”, since for a couple of years Hunt ran a brewery in Bristol – an episode which is significant in the history of porter, since Hunt’s memoirs contain some important evidence on porter brewers’ attempts to make a dark drink while brewing with the far more economic pale malt.

In April 1802, a month after the Treaty of Amiens had ended 10 years of warfare against revolutionary France, the British government put up the tax on strong beer by 25 per cent, to 10 shillings a barrel, and raised the tax on malt by almost four fifths, to 2s 5d a bushel. At the same time, the Act of Parliament introducing the higher taxes, the Duties on Beer, etc Act 1802, also put into statute law a specific prohibition against making beer or ale with anything except malt and hops.

Matthew Wood, a City of London-based druggist (and, from 1804, hop dealer) with a clientele of brewers decided that since it was now apparently legal to put anything made from malt into beer, then a colouring made from malt extract should be permissible, and in May 1802 he duly registered a patent process for “Preparing a colour from malt for the purpose of colouring spirits wines and other liquors.” The fact that Wood’s patent application, which described mashing the malt, boiling the extract until most of the water was driven off and then roasting it in iron pans “until the saccharine quality is destroyed, and the whole is nearly reduced to a calx,” did not mention beer specifically may be because he did not want to tip off anyone too early that he was attempting to patent something that the Excise authorities had long declared was against its regulations. He invested £2,000 in the patent, apparently having been given a guarantee from the senior Secretary to the Treasury, Nicholas Vansittart, that his malt colouring would be regarded as lawful, since it used an ingredient, malted barley, upon which tax had been paid.

The Commissioners of Excise disagreed. They instigated prosecutions and seizures of casks of porter colouring materials against brewers who bought Wood’s product, on the grounds that they were adding an illegal adjunct to their porter. The excise commissioners insisted that the “malt” that the Duties on Beer Act 1802 had defined as one of only two permitted ingredients in beer and ale meant only those products customarily made by maltsters, not Wood’s patent colouring. Allowing druggists to supply brewers with beer colouring would “open the widest Door for introducing Ingredients forbidden by Law,” they declared. However, the brewers, and Wood (who became a City of London alderman in 1807), fought back, with the colouring continuing on sale.

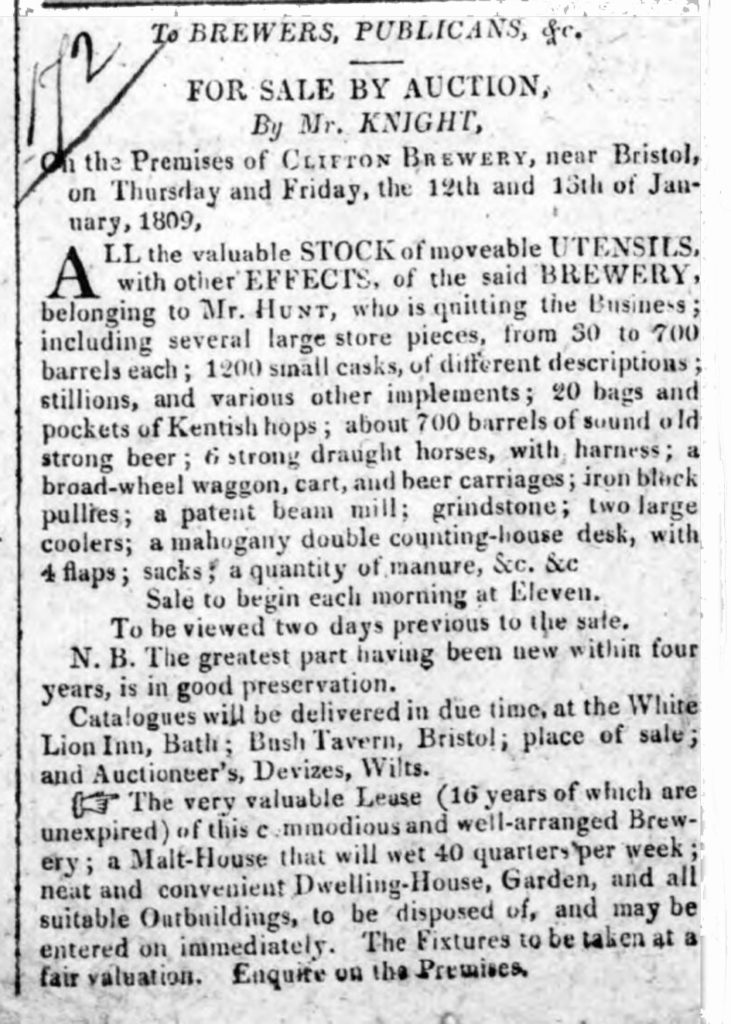

Henry “Orator” Hunt, the radical politician who was the main speaker at the meeting in Manchester in August 1819 that turned into the “Peterloo Massacre”, had a run-in with the revenue over Wood’s colouring in 1808. Hunt ran a brewery at Jacob’s Wells in Bristol, the Clifton Genuine Beer Brewery, from at least 1807 to 1809. It had been started when a brewer friend called Racey – evidently the son son of the James Racey whose brewery in Bath went bust in 1804 – asked Hunt to put up the money to convert a former distillery at Jacob’s Well into a brewery. Hunt claimed he had designed the whole layout of the brewery himself:

I took advantage of the declivity of the hill, on the side of which the premises were situated, to have it so constructed that the whole process of brewing was conducted, from the grinding of the malt, which fell from the mill into the mash-tun, without any lifting or pumping; with the exception of pumping the water, called liquor by brewers, first into the reservoir, which composed the roof of the building. By turning a cock, this liquor filled the steam boiler, from thence it flowed into the mash-tun; the wort had only once to be pumped, once from the under back into the boiler, from thence it emptied itself, by turning the cock, into the coolers; it then flowed into the working vats and riving casks, and from the stillions, which were immediately above the store casks into which it flowed, only by turning a cock. These store casks were mounted on stands or horses, high enough to set a butt upright, and fill it out of the lower cock; and then the butts and barrels were rolled to the door, and upon the drays, without one ounce of lifting from the commencement of the process to the end. This was a great saving of labour.

However, according to Hunt, Racey turned out to be fraudulently raking off cash from the brewery, and when challenged he “sailed for America, bag and baggage”. (It seems highly likely that this is the James Racey who married Anne Hull in New York in 1810 and then settled in Canada, buying the distillerie de Beauport just to the east of Quebec City the same year, and converting it to a brewery.) Hunt found himself having to run the brewery in an attempt to get back at least some of the money he had invested, and described his subsequent clash with the Excise over Wood’s colouring in his memoirs, written while he was in jail in 1820 for “sedition” after the events at St Peter’s Field:

When the act was passed, making it a penalty of two hundred pounds to use any drug, ingredient, or material, except malt and hops, in the brewing of beer, Alderman Wood obtained a patent for making of colouring, to heighten the colour of porter. This colouring was made of scorched or burnt malt, and it was mashed the same as common malt, which produced a colouring of the consistency of treacle, and having nearly its appearance. As this patent was very much approved of, almost every porter brewer in England used it in the colouring their porter; and amongst that number I was not only a customer of the worthy alderman for colouring, but I was also a considerable purchaser of hops from the firm of Wood, Wiggan [sic—properly Wigan] & Co in Falcon Square. I had just got down a fresh cask of this colouring, and it was standing at the entrance door of the brewery, where it had been rolled off the dray, when news was brought me that the new exciseman had seized the cask of colouring, and had taken it down to the excise office. I immediately wrote to Wood, Wiggan & Co to inform them of the circumstance; upon which they immediately applied to the board of excise in London, and by the return of post I received a letter from Messrs Wood, to say, that an order was gone off, by the same post, to direct the officers of excise in Bristol to restore the cask of colouring without delay; and almost as soon as this letter had come to hand, and before I could place it upon the file, one of the exciseman came quite out of breath to say that an order had arrived from the board of excise in London, to restore the cask of colouring, and it was quite at my service, whenever I pleased to send for it. I wrote back a letter by the fellow, to say, that as the exciseman had seized and carried away from my brewery a cask of colouring, which was allowed by the board of excise to be perfectly legal to use, as it was made of malt and hops only, unless, within two hours of that time, they caused it to be restored to the very spot from whence it was illegally removed, I would direct an action to be commenced against them. In less than an hour the cask of colouring was returned, and the same exciseman who had seized it came to make an apology for his error. His pardon was at once granted, and so ended this mighty affair; and I continued to use the said colouring, as well as did all the porter brewers in Bristol, without further molestation, as long as I continued the brewery; never having had any other seizure while I was concerned in the brewery.

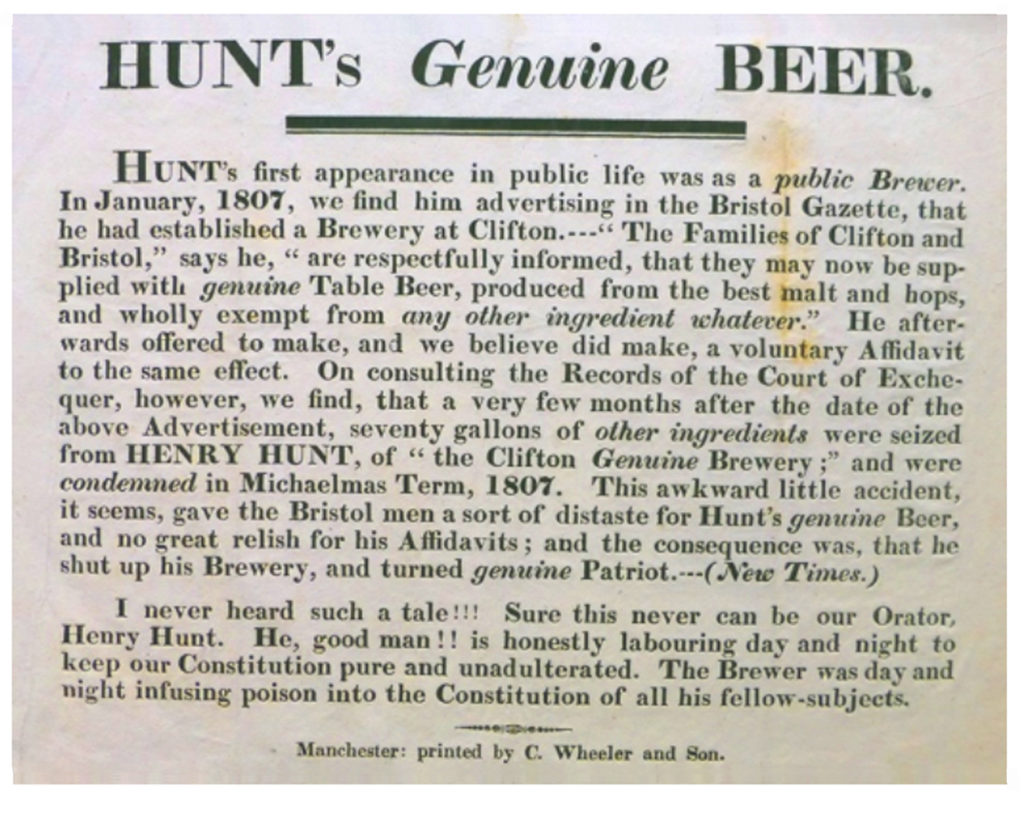

The story appears in Hunt’s biography because he was responding to an attack on his brewing career by one of his political enemies, Dr John Stoddart, the editor of the “ultra-Tory” New Times newspaper, in an article in July 1819, just before Peterloo. The newspaper claimed that despite Hunt advertising in the Bristol Gazette in January 1807 that his beer was “wholly exempt from any other ingredient whatever” than the best malt and hops, “a very few months after the date of the above advertisement, seventy gallons of other ingredients were seized from Henry Hunt of ‘the Clifton Genuine Brewery;’ and were condemned in Michaelmas Term 1807.” The result of “this awkward little accident”, the New Times claimed, was that it “gave the Bristol men a sort of distaste for Hunt’s genuine beer … and the consequence was that he shut up his Brewery.” The New Times’s attack was reprinted word-for-word by more than a dozen other local newspapers of the Tory persuasion, from Inverness to Cornwall, the following month, after Peterloo, and turned into a pamphlet circulated in Manchester.

Curiously, 11 years earlier Hunt had given a completely different version of the story to his local paper. He had already made himself unpopular with the establishment in Bristol in 1807 when he popped up at the hustings for the general election that May and attempted to interrupt the cozy stitch-up of the city’s two parliamentary seats by the Tories and Whigs by nominating a third, more radical candidate. When his bid to put another name on the list was refused Hunt’s supporters pelted the Tory candidate “so vigorously with mud and sticks that he was forced to leave his gilded car and beat a retreat.” The mob was only diverted, it was claimed later, by Hunt offering to distribute two free butts of beer at his brewery. In 1808, replying to an accusation that “unlawful ingredients” had been seized upon his brewery’s premises, Hunt said:

When the last act of parliament passed, prohibiting the use of “any ingredient or material. except malt and hops, to be made use of tin the brewing of beer or porter,” Messers Wood, Wigan and Co hop-factors, in London, obtained a patent for making a colouring for Porter with burnt malt only. Two casks of this Colouring was [sic] sent to me, but before I admitted it into my brewhouse, I sent to the Exciseman to know if it were legal to make use of it for colouring porter, shewing him the permit or certificate that I received with the casks. His answer was, he did not know, but he would go to the supervisor and enquire. On his return, he said that they had no authority to permit it to be used, and they must take a sample of it. I desired that they would take the whole, as I should not, under such circumstances, suffer it to be placed in my brewery: my horses took it for them to the Excise-office. I immediately stated the case to the Commissioners of Excise, from whom I received no answer. Mr Wood’s patent colouring has never been returned to me, nor have I since heard any thing of it.

Whichever story of Hunt’s was accurate, it is clear Wood’s beer colouring was still not definitively legal even in 1808. The brewing trade was evidently split over whether Wood’s colouring should be supported or not, with the largest porter brewers, such as Whitbread, Barclay Perkins and Felix Calvert, opposed, apparently for fear that allowing sugar and malt colouring would take some of the pressure off their smaller rivals, and others, such as Meux Reid and the big Windsor brewer John Ramsbottom, in favour. The battle was fought in parliament, where the porter brewers had eight MPs at the time and the country brewers four, but victory for the colourists only came with an alliance with the West Indies sugar plantation interest, who were keen to find a new outlet for their product (and helped by the Treasury, which wanted to see more pale malt used, as this was apparently easier to supervise by the excisemen than brown malt, and thus less likely to avoid tax). In June 1811 an Act was passed allowing the colouring of porter (but not ale or pale beers) with “burnt brown sugar and water” (but not molasses), with a licence to make porter colouring costing £5 and duty charged on each barrel of colouring of 10s a time.

The Colouring of Porter Act lasted just half a decade before it was repealed and a new Act passed, in June 1816, banning even burnt sugar from being used for colouring beer from July 6 the following year. Licence fees and duty from burnt-sugar colouring had brought in £82,000, but the excise authorities declared that there was evidence that other illegal ingredients were being sneaked into porter along with the colouring. Cometh the hour, cometh the inventor: in March 1817, four months before burnt sugar colouring became illegal, Daniel Wheeler, who had been making sugar colouring at his premises off Drury Lane in central London, unveiled via a patent application a new method of manufacturing colouring from malt, upon which duty had been paid (thus making the colouring legal). His process heated the malt to 400ºF and more, to produce “a substance resembling gum and extractive matter of a deep brown colour readily soluble in hot or cold water.”

Wheeler told the 1818 House of Commons committee on the quality of beer that with brown malt, “thirty-two parts of it to forty-eight of pale,” or 40 per cent, “gives about the porter colour.” However, “The high-dried brown malt, from the heat to which it has been exposed, has lost a considerable quantity of its sugar. I have made many experiments upon it myself, and … that high dried malt will not produce, or has not, from any experiments, produced more than one fourth of the spirits compared to that of pale malt.” Using his invention, though, “one part of the patent malt will give as much colouring as thirty-two parts of the malt I have been speaking of” – in other words, brewers needed less than 2½ per cent of Wheeler’s patent malt to give a satisfactory colour to their porter.

Dr Thompson’s Annals of Philosophy for December 1817 declared of Wheeler’s invention: “There are few patents that promise to be of such great national importance.” To get the “deep tan-brown colour” and “peculiar flavour” of “the best genuine porter,” two parts of brown malt were required to three parts of pale malt. “The price of the former is generally about seven-eighths of the latter; but the proportion of saccharine matter which it contains does not, according to the highest estimate, exceed one-half that afforded by the pale malt, and probably on an average scarcely amounts to one-fifth…it follows that the brewers are paying for the colour and flavour of their liquor one-fifth of the entire cost of their malt.” The savings that brewers could make with Wheeler’s patent malt meant the end of temptations to use illegal materials such as cocculus indicus, and “The revenue will be benefited by the increased consumption which will necessarily result from an improvement in the quality of the porter; and both the revenue and public morals will derive advantage from the greatly diminished temptation to fraudulent practices.”

The big porter brewers quickly took up his invention, with Whitbread recording stocks of patent malt in the same year, 1817, and Barclay Perkins by 1820 (though curiously, in 1819, Rees’s Cyclopedia claimed that “In Mr Whitbread’s works no colouring matter is employed, as he uses a portion of brown malt”), and the Plunkett family opening a plant in Dublin in 1819 to supply Irish porter brewers. But alas for Wheeler, his patent was swiftly challenged. A coffee roaster based in Northumberland Alley, off Fenchurch Street, in the City of London called Joseph Malins began roasting malt himself and selling it to “various” brewers for colouring, to the “considerable injury” of Wheeler’s business. Wheeler sued Malins for patent infringement and the two sides clashed in the Court of Chancery in August 1818, with Wheeler claiming his patent had been “pirated” and Malins insisting that there was no piracy, since the brown malt he sold to porter brewers had been heated in “a common coffee-roaster,” which had been in use for more than a century before Wheeler’s patent.

Unfortunately for Wheeler, the case was bumped to a higher court, the Court of King’s Bench, to decide whether his patent was actually valid, and at a hearing in December 1818 the newly appointed Lord Chief Justice, Sir Charles Abbott, directed the jury to find that it was not. Wheeler’s patent application had been for “A new and improved method of drying and preparing malt.” But, Abbott said, the process the application described was not, in fact, “preparing” malt, it was a process for making malt more soluble and colouring the liquid. With the patent declared void, in March 1819 Wheeler’s case in the Court of Chancery was dismissed with costs.

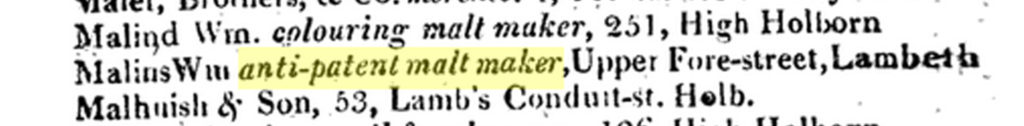

The victory over Wheeler was a welcome win for the Malins family in the courts: in May 1818 Joseph Malins’s father, William, had been fined £100 by the Court of Exchequer for having on his premises more than 1,500lb of roasted and ground peas and beans with the intention of passing them off as coffee, and a month later William was fined the huge sum of £2,000 by the same court after being found guilty of manufacturing 100lb of imitation tea, from hawthorn and blackthorn leaves plus colouring, and selling it to grocers in London. Daniel Wheeler continued to describe himself as a “patent malt manufacture,” though by January 1819, when he had moved from Bloomsbury in central London to Croydon in Surrey, he had been declared bankrupt. Cheekily, perhaps, William Malins was calling himself an “anti-patent malt maker” in 1823, when he was based in Upper Fore Street, Lambeth.

However, although Wheeler was unable, as he must have hoped, to turn “patent malt” into a personal fortune, its adoption did indeed swiftly revolutionise the brewing of porter, as the use of brown or blown malt shrank or disappeared. (Ironically, malt roasted to Wheeler’s specifications continued to be known as “patent” malt for more than a century, even though the patent had been overturned.)

Hunt, meanwhile, left the brewery business in 1809, ten years before Peterloo. By 1811 the brewery at Jacob’s Wells was being run by a J Highett from Weymouth, who was brewing strong beer, porter, Burton ale and table beer. It was up for sale early the next year, and again in 1813, when the equipment included “a new copper furnace, containing 20 barrels, never used.” It seems to have had several subsequent owners, but by early 1827, when the site was put up for sale, it was being described as a “late Brewery”.