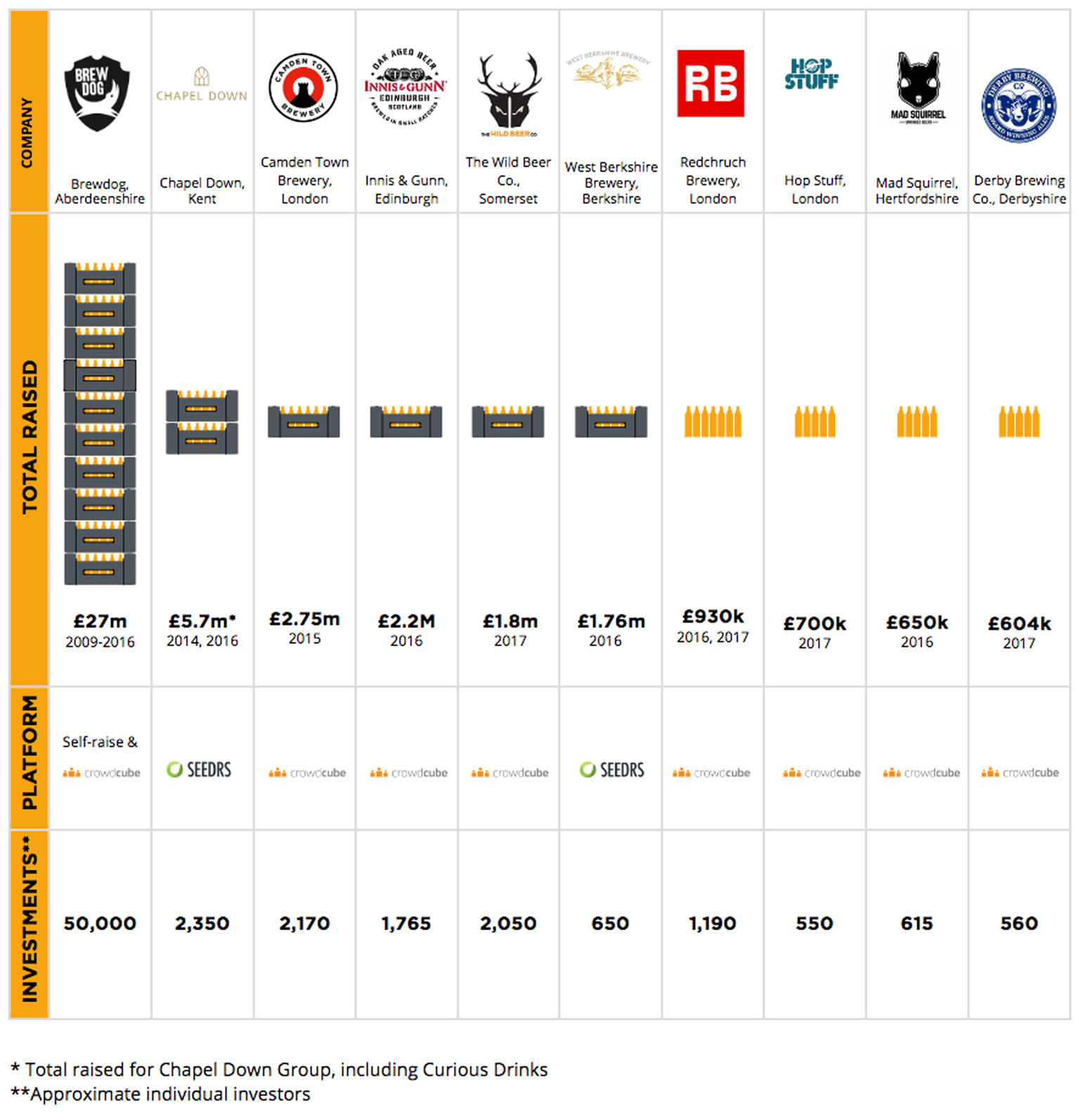

A total of £50m has been raised in the UK over the past four years in crowdfunding efforts by more than 40 different craft breweries, and half a dozen craft beer retail operators who have tapped tens of thousands of – overwhelmingly male – investors.

More than half the money raised went to just one company, BrewDog, the maverick Scottish brewer, recently valued at almost £1 billion, but other big beneficiaries of the remaining £23 million raised include Chapel Down Group, owner of Curious Brew, which gathered a total of £5.66m; Camden Town Brewery in North London, which raised more than £2.75 million from 2,173 investors via Crowdcube before being sold for £85 million to the international giant AB Inbev in December 2015; Innis & Gunn of Edinburgh, which raised £2.2 million from almost 1,800 investors; and the Wild Beer Company of Somerset, which brought in £1.8m from just over 2,000 backers.

The money is continuing to roll in: Redchurch Brewery in East London recently closed its second fundraising drive through the crowdfunding platform Crowdcube, raising another £433,000 from 688 investors to add to the £497,000 it brought in last year. Also on Crowdcube, The BottleShop, a craft beer importer and distributor with, currently, three bars of its own and plans for more, has just closed its own equity crowdfunding campaign with £403,000 in funding from more than 380 investors

Top 10 UK brewery crowdfunding efforts

But how many of those investors will ever see a decent return on their money, other than the warm glow of owning a small slice of the maker of their favourite beers? With three quarters – 18 out of 25 – of the companies involved for which financial records have been published reporting losses for their last financial year, the answer is likely to be: “Not many, and even then, not for quite a while”. The UK’s financial watchdog, the FCA, warns in the section on crowdfunding on its website: ” It is very likely that you will lose all your money. Most investments are in shares or debt securities in start-up companies and will often result in a 100 per cent loss of capital as most start-up businesses fail.” Earlier this year the Guardian quoted figures from the Insolvency Service showing that 19 drinks manufacturers went sternum to the sky in 2014, 23 in 2015 and 24 in the first nine months of 2016.

But how many of those investors will ever see a decent return on their money, other than the warm glow of owning a small slice of the maker of their favourite beers? With three quarters – 18 out of 25 – of the companies involved for which financial records have been published reporting losses for their last financial year, the answer is likely to be: “Not many, and even then, not for quite a while”. The UK’s financial watchdog, the FCA, warns in the section on crowdfunding on its website: ” It is very likely that you will lose all your money. Most investments are in shares or debt securities in start-up companies and will often result in a 100 per cent loss of capital as most start-up businesses fail.” Earlier this year the Guardian quoted figures from the Insolvency Service showing that 19 drinks manufacturers went sternum to the sky in 2014, 23 in 2015 and 24 in the first nine months of 2016.

Fanboy investing can be fun, but is not necessarily lucrative: and, like all gambling ventures, you should only risk money you can afford to lose. Indeed, given the general lack of form available on those asking you to fund their dreams, fanboy investing is actually worse than most forms of gambling. At least when it comes to the 2:30 at Haydock Park you can see how the horses performed in the past. Few start-up brewers have ever begun a company before to let you gather some idea of their business savvy. As Justin Hawke of Moor Beer told the Guardian, talking about crowdfunding craft brewery start-ups: “It’s a largely unregulated and unknown way of investing used by people who a bank wouldn’t lend to because they don’t have a sound business model. It allows hobbyists to entertain their notions. BrewDog would point to themselves as the exception, but a lot have failed and will fail in the not-too-distant future.”

You can read the complete report I put together for the investment advisory firm OFF3R on crowdfunding and the craft beer scene in the UK here, but I thought I’d share a few highlights with Zythophile readers. The number of individual investments across the nearly 50 beer and brewing companies covered by the report totals more than 65,000, though how many people that represents is hard to estimate.

You can read the complete report I put together for the investment advisory firm OFF3R on crowdfunding and the craft beer scene in the UK here, but I thought I’d share a few highlights with Zythophile readers. The number of individual investments across the nearly 50 beer and brewing companies covered by the report totals more than 65,000, though how many people that represents is hard to estimate.

According to Crowdcube, which has seen the largest number of beery crowdfunding efforts on its site, a fifth of its investors in beer-related companies put money into two or more ventures, which still suggests more than 50,000 people now own craft. brewery stakes. A huge proportion are men: 85 per cent, against an overall split among Crowdcube investors generally of 73 per cent male to 27 per cent female, pointing to “fanboy” investing by male beer drinkers in their favourite brew. The average age of brewery investors on Crowdcube is 41, so they can be presumed to know at least a little about financial risk.

According to Crowdcube, which has seen the largest number of beery crowdfunding efforts on its site, a fifth of its investors in beer-related companies put money into two or more ventures, which still suggests more than 50,000 people now own craft. brewery stakes. A huge proportion are men: 85 per cent, against an overall split among Crowdcube investors generally of 73 per cent male to 27 per cent female, pointing to “fanboy” investing by male beer drinkers in their favourite brew. The average age of brewery investors on Crowdcube is 41, so they can be presumed to know at least a little about financial risk.

Geographically the largest proportion of brewery investors on Crowdcube, at 27 per cent, more than one in four, comes from London, although London has less than 14 per cent of the UK’s total population: this may reflect the fact that a fair number of big brewery crowdfunding efforts have come from London brewers such as Hop Stuff (£700,000), Redchurch (£930,000) and Camden Town. The next biggest regions for brewery crowdfunding investors on Crowdcube come from the South East of England, with 10 per cent, and Scotland, with 9 per cent: again, Innis & Gunn and BrewDog have been big raisers of capital via crowdfunding.

The most popular crowdfunding platform among British brewers is Crowdcube, with more than two dozen brewery clients, for which it has raised more than £11 million. Its rival Seedrs has just two brewery clients and the craft beer distributor Eebria on its books, the same number of beer sector clients as the Angels Den platform, but has raised more than £7.8 million for them, against Angels Den’s £166,000 for its three brewery firms.

Ignoring BrewDog, the average sum raised by all brewery and beer sector equity-based crowdfunding efforts at a time is £626,000, 10 per cent higher than the average raised across all sectors on Crowdcube of £568,000 per fundraising campaign and 28 per cent more than the average for the food and beverage sector as a whole on Crowdcube, £490,000.

The largest sums have been raised through equity-based schemes, but around a dozen new small breweries have brought in more than £100,000 between them in rewards-based crowdfunding, offering everything from T-shirts to a day at the brewery, and asking for sums as low as £5 at a time. Among the most successful rewards-based fundraisers have been Crossed Anchors of Exmouth, which brought in almost £38,000 from 364 supporters in just 49 days, offering rewards including the right to name one of the brewery fermenting vessels, with a “christening party” at the brewery, for £2,000; and Wildcraft Brewery in Norfolk, which raised just short of £22,000 from 331 supporters in 63 days after offering rewards including a “brew your own beer” day for £500. Both used the Crowdfunder site, as did the organiser of probably the smallest brewery fundraising venture, Three Spires Brewery in Lichfield, Staffordshire, which raised £320 from nine subscribers in January this year to pay for equipment and ingredients, with rewards of free beer. (Breweries offering equity also, typically, offer rewards as well, ranging from discounted beer to invitations to the AGM.)

The potential returns available through making a crowdfunding investment look, on the surface, very attractive. Seedrs has claimed that its investors have seen a 14.4pc annualised return, rising to 41.87pc after tax relief. However, this represents growth in the share price only, with shareholders not actually seeing that return appear in their bank accounts every year. The other big criticism of crowdfunding – apart from the risk to your money – is that investors find it hard to get their hands on their rewards, with no, or only very limited retail markets in which to sell their shares.

Some investors in brewery crowdfunding ventures have certainly seen spectacular paper returns, however. According to BrewDog, at the company’s current valuation of almost £1 billion, anyone who put money into its first Equity for Punks crowdfunding, which closed in February 2010, has seen the value of their investment increase 2,765 per cent in seven years, a compound growth rate of almost 275 per cent a year. Even investors in its most recent crowdfunding round, EFP IV, which closed in April 2016, saw a 177 per cent increase in the value of their holding over 12 months. The company has run annual opportunities for its shareholders to sell up via Asset Match, a website that enables dealings in private companies, and one BrewDog shareholder revealed earlier this year that she had invested £2,000 in EFP II in 2011, sold half her holding via Asset Match in 2016 for £8,000 – a 70 per cent compound annual return – and still had a holding worth, on paper, £53,000. However, when BrewDog sold a 22 per cent slice of itself to TSG in April this year, EFP investors were allowed themselves to sell just 15 per cent of their individual shareholdings, capped at 40 shares per investor.

Camden Town Brewery investors saw an even faster return, with the company raising £2.75 million via Crowdcube in April 2015 for 5.37 per cent of the business, giving an enterprise value of £51 million, and selling out to the giant brewing concern AB InBev just eight months later for a reported £85 million – a compound growth rate of 7.6 per cent a month, or 45 per cent a year. However, BrewDog and Camden Town are rarities even among crowd-funded ventures as a whole, and Seedrs warns that most investors are unlikely to see returns within five to seven years, assuming they get anything at all. And although the true figures are unlikely ever to appear, it seems probable Camden Town wasn’t true “crowdfunding” in the sense that most money came from “ordinary” investors: it’s fairly certain that most of the cash was put up by friends and associates of Jasper Cuppaidge and his father-in-law, the millionaire adman Sir John Hegarty, and merely channeled through crowdcube. One brewery finance director told me, on conditions of anonymity, that he was “100 per cent convinced” most of Camdem Town’s cash was already raised “off-platform” from investors before crowdfunding began.

FAILURES

With half of all new business enterprises reckoned to fail before five years are up, it is no surprise that crowdfunded breweries have still got into trouble, despite the due diligence most crowdfunding platforms impose and, sometimes, the presence of high-profile experienced investors. Jon Moulton, founder of the private equity firm Alchemy Partners, put £25,000 into the North East of England brewer Delavals, founded in Blyth, Northumberland in 2010. as it attempted to raise £400,000 in January 2015 by selling 30 per cent of the company via the Investingzone.com crowdfunding platform. Delavals was the officially licensed brewer to the National Trust and operated the Trust’s beer club. The fundraising failed, and Delavals went into liquidation in May 2015, blaming market saturation and extremely competitive beer pricing, and the fact that it had not raised sufficient cash to pay for the marketing support to bring in sufficient sales to keep it going.

Other failures include Brüpond, based in Leyton, East London, which raised £ 45,000 from 45 investors on Crowdcube in 2012 but went into liquidation in September 2013; and Little Brew, originally of Camden in North London, which raised £109,000 on Crowd Cube for 27 per cent of its equity early in 2014, moved its operations to York, and then collapsed at the start of 2016. Quantock Brewery in Somerset, which raised £120,000 on Crowdcube in 2015, entered administration in January this year, and although it was subsequently acquired by an unnamed investor and is still running, presumably those Crowdcube punters have kissed their cash farewell.

Crowdfunding attempts by brewers also miss their targets and never take off. Among recent failures, Burton Town Brewery sought to raise just £25,000 last September on Crowdfunder but attracted only 13 supporters.

HISTORY

The history of crowdfunding in the brewing sector actually dates back more than two centuries, to the Golden Lane Genuine Beer Brewery, which opened near the Barbican in the City of London in 1805 and raised more than £250,000 – equivalent to perhaps £19 million today – from 600 “co-partners”, including 120 publicans, with the aim of brewing cheaper beer than the then big brewers were making.

The Golden Lane Brewery eventually went into a steep decline, however, finding it impossible to compete on price without lowering the quality of the beer, and collapsed in the mid-1820s. It was more than 60 years before breweries that were originally private partnerships began selling their shares to the public, the first being Guinness in 1886, which put up two thirds of its equity at a valuation of £6 million. Almost 20,000 investors applied for shares, and only 6,000 were successful. The demand for shares in Guinness encouraged other brewers to float on the stock market: but these were all conventional share sales involving brokers and stock exchanges.

It was not until 1995 when anyone tried anything similar to the Golden Lane Brewery’s “crowd fundraising” venture. That year Jim Koch, founder of the Boston Beer Company in the United States, maker of Samuel Adams lager, put coupons on six-packs of his beer allowing customers to buy 33 shares in the 10-year-old company at $15 a share, a total investment of $495. The offer brought in the equivalent of more than £40 million from tens of thousands of fans of Samuel Adams beer. Koch told NPR’s How I Built This podcast last year: “The investment banks freaked out about it, they told me, ‘You can’t do it, it would never work,’ all these reasons not to. But I stood my ground, I knew the investment banks were going to make money on this, so they would let me do it if I refused to compromise. Eventually they came round, and we got 130-some thousand people who sent in cheques. We got $65 million, and that was the first time something like that had been done.”

That $65 million Sam Adams raised on its own is almost exactly the same sum all of Britain’s craft beer brewers have raised together, of course. Crowdfunding by craft beer brewers is certain to continue: but if you’re tempted to put your own money up, be sure you can afford to lose it, and do not expect to make the fortune Jim Koch made.

I think Tisbury was the first to make a share offer to the public in modern times, at some point in the 80s and possibly when they changed their name to Wiltshire Brewery around 1985. The fund raising was done by stockbroker James Capel. The brewery was certainly operating in 1982 but I’m not sure when it went under – the building is now flats.

You mention Jon Moulton. He’s a very nice man but has a history of ups and downs in investing, although the net balance is enough to keep him in tax exile in Guernsey. I think he was at Alchemy when he backed the buy-out of Ushers in 1990. After a rather public bust up with colleagues, he went on to found Better Capital and remains there today.

I’d be really interested to know what the investors are generally expecting by way of a return from this sort of thing – I mean, do they see it as a surefire road to fabulous wealth, or more of a fanclub-with-benefits? I’d always assumed that it was mostly the latter, but given the average investment per person in some of those examples I’m not so sure…

I invested in a friend’s business many years ago – interest rates were roaring away at the time, and they agreed to pay me 11% p.a. on my investment (long-term savings accounts were paying 9 or 10 at the time). I only got a couple of payments back before the shop went bust, sadly.

But I was interested when these offers started to proliferate, and wondered if they might also give an investor a bit of a return on their money. Apparently not. To quote a series of tweets from Wild when I inquired along these lines:

– shares don’t have a projected return. Have you requested the full business plan? That will give you a full vision of our plan

– it’s an equity raise, not a loan or a bond, you are purchasing shares in the company

– as the business grows the shares go up in value. It’s a longish term investment.

So there you go – you put in a grand, which buys you (say) 0.01% of a company valued at £10 mill; five years down the line, when the company’s valued at £50 mill, your £1K has turned into £5K. Or it has if you can get it out at that rate, which is up to the company (I gather that BD have actually been quite good at letting early investors cash out). In the mean time you haven’t got any kind of return on your money – unless and until you can cash out, it looks an awful lot like lending money out at 0%, in other words. But hey, freebies!

[…] Best known for his writing on British beer history, Mr Cornell is also a dedicated industry commentator, and this sharp piece on crowdfunding from July remains relevant: […]

[…] Cornell gave a detailed rundown of some of the problems with crowdfunding in beer a few years ago: it’s not real investment in most cases; and lots of crowdfunded businesses fail, or […]

Speaking as someone who put some money into Five Points in Hackney I definitely fall into the fanboy category. I saw it as a chance to support a well run brewery with sensible and realistic ambitions. And they brew a decent pint as well. I don’t suppose I’ll get my money back, but they organise interesting events and have a few other benefits as well.