I live half-way between Richmond and Hampton – which gave a small but still slightly odd twist to my 3,000-mile journey last month to deliver a talk in another town halfway between Richmond and Hampton. Different Richmond and Hampton, of course: the pair in Virginia, not the ones in the western suburbs of Greater London†.

I live half-way between Richmond and Hampton – which gave a small but still slightly odd twist to my 3,000-mile journey last month to deliver a talk in another town halfway between Richmond and Hampton. Different Richmond and Hampton, of course: the pair in Virginia, not the ones in the western suburbs of Greater London†.

The talk was in Williamsburg, Virginia, as part of a terrific two-day event called Ales through the Ages featuring more than a dozen speakers from Europe and the United States, put on by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Williamsburg was the capital of Virginia until 1780, when capital status was transferred to Richmond, and the town went into a decline that lasted through until the first quarter of the 20th century. Ironically, its decline was its subsequent salvation. Since there was no incentive (or cash) to knock them down and rebuild them, many of Williamsburg’s original colonial-era buildings remained standing, albeit increasingly rough-looking. Eventually, in the late 1920s, with campaigners concerned that genuine American history was literally falling to pieces in front of them, John D Rockefeller jr, whose father, one of the founders of Standard Oil, was the richest man in the world, agreed to fund what would become Colonial Williamsburg, a living reproduction of 18th century America. Today Williamsburg is a considerable tourist attraction with restored buildings, actors walking the streets dressed like 18th century colonials and, of course, demonstrations of the lifestyles and crafts of the 18th century. Naturally enough that includes food and drink, and naturally enough that includes brewing.

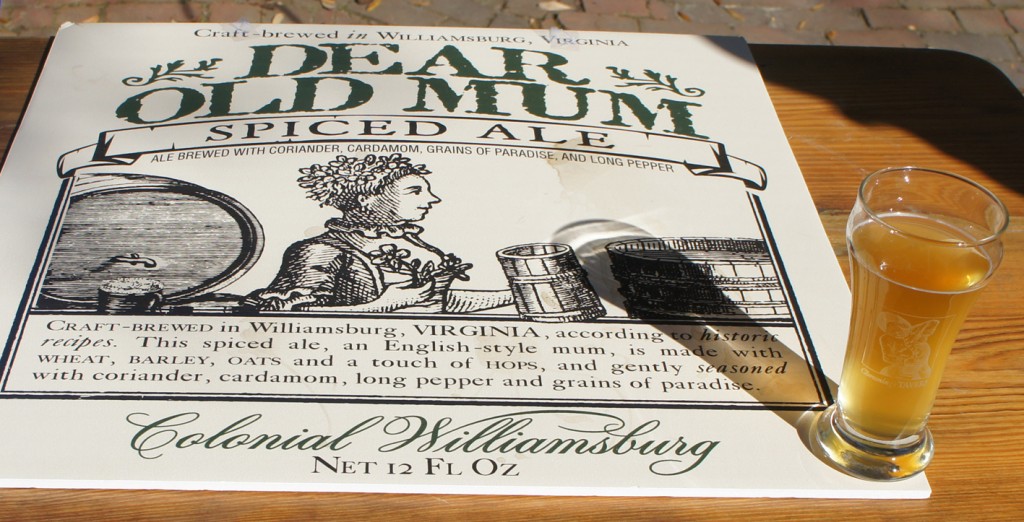

The man in charge of the Historic Foodways department at Colonial Williamsburg, Frank Clark, has a deep interest in the history of beer, and gets to demonstrate 18th century-style brewing on probably the most authentic historic brewing set-up I have ever seen: several wooden tubs, a number of basins and saucepans, and a large copper cauldron that is swung over the wood fire in the scullery of the (reconstructed) Governor’s Palace to heat the water for mashing and boil the resultantwort with hops. The beers he and his colleagues make don’t get sold, but one of the local Williamsburg breweries, Alewerks, taps Frank’s knowledge to make a couple of “authentic” 17th/18th century beers for sale in the local taverns, Dear Old Mum and Old Stitch, the first loosely based on an Anglo-German spiced ale, the second the name of a brown ale found in The London and Country Brewer from the 1730s.

I’m guessing (I never actually asked him) it was Frank’s idea to put on the conference, and despite what seemed to me to be the extremely high price of $325 (£220) for the full two-and-a-half day ticket (and that’s before travel and accommodation), there were still more than 120 people in the paying audience, from as far away as California. Could we get away with anything like that in the UK? I suspect you’d start hitting serious consumer resistance at a fifth of that price, frankly. Was it worth it? Well, I enjoyed it hugely, but of course, I was being paid to be there … still, here’s the speaker line-up – see what you think:

Saturday

Travis Rupp, who combines being an “adjunct professor” at the University of Colorado lecturing on classics and anthropology with being the packaging supervisor at Avery Brewing in Boulder, was first on stage. Travis is writing a book on the beginnings of beer in the ancient Mediterranean, which, if his talk on the subject at the Williamsburg conference is a guide, will be a must-buy. He touched on everything from palaeoecology – the changes in ancient Syria, from heavy forestation around 10,000 BC to the trees being replaced by wild barley 2,000 years later – to the oldest known brewery in Egypt, at Tell el-Farkha, some 3,000 years and more BC, to evidence of brewing in Minoan culture. Travis seemed to be suggesting, if I was following him properly, that the Sumerians taught the Egyptians how to brew, who taught the Greeks how to brew, who taught the Romans how to brew, and the Romans taught the Celts and Germans: the last part, I have to say, I don’t believe at all. Still, cracking start to the weekend

Stan Hieronymus, writer of excellent books on subjects such as hops, monastery brewing and wheat beer, and owner of the Appelation Beer blog, presented In Search of an Indigenous American Beer Style, which covered territory that was pretty much entirely new to me: the tiswin corn (maize) beer drunk by the Apaches, for example, and the choc beer of the Choctaw Indians of Oklahoma, which supposedly included tobacco as well as hops and barley; and also Kentucky Common and Pennsylvania swankey, among other beers and beer styles unique to America.

Stan Hieronymus, writer of excellent books on subjects such as hops, monastery brewing and wheat beer, and owner of the Appelation Beer blog, presented In Search of an Indigenous American Beer Style, which covered territory that was pretty much entirely new to me: the tiswin corn (maize) beer drunk by the Apaches, for example, and the choc beer of the Choctaw Indians of Oklahoma, which supposedly included tobacco as well as hops and barley; and also Kentucky Common and Pennsylvania swankey, among other beers and beer styles unique to America.

Karen Fortmann, a research scientist at White Labs, the yeast specialists, in San Diego, talked about the “family tree” of brewer’s yeast – a difficult pedigree to draw up, since as Karen said, “If yeast is in an environment where it’s encouraged to hybridise, it will.” And it has, except we’re finally working out exactly who the mummy and daddy were in, eg, lager yeast. Or possibly “mummies and daddies” – according to Karen, genetic studies are suggesting two “domestication events” for brewing yeasts.

Frederik Ruis, a brewer and historian from the Netherlands, filled the tricky post-lunch slot with a presentation on “One Thousand Years of Brewing with Hops”, which had some interesting revelations and yet another controversial claim. Archaeological finds, he said, show much of the earliest use of hops in the Baltic and North Sea areas, particularly around Bremen and Hamburg, taking the focus away from Southern Germany, which is normally given primacy in the use of hops in brewing, and giving it to the Vikings. He also suggested that continental gruit or grout was not the herb mixture everyone supposes, or even herbs mixed with grain, but instead concentrated wort infused with herbs, which was then sold by the gruit houses to their local brewers. I look forward to reading more.

Andrea Stanley, of Valley Malt in Massachusetts and John Mallett, director of operations at Bell’s Brewery in Kalamazoo, then dressed up in period costume as female maltsters and brewers from the past for “Maltster-piece Theatre”, which gave the audience an insight into the lives and trials of brewsters from centuries ago, via a well-written script that succeeded in the difficult double of being both informative and ha-ha funny.

Finally for the day, Edward Bourke, a former Guinness technical expert who wrote a book on the brewery and the family in 2009 called The Guinness Story, presented the history of brewing in Ireland, including some revelatory information from late 18th century Guinness brewing books. The ingredients for a brew of 20 barrels of ale from August 1797 were four barrels of brown malt (Irish brewers measured malt in barrels, generally reckoned to be the equivalent of 168 pounds, one and a half hundredweight ) and six barrels of pale malt, plus 38 pounds of hops, slightly less than two pounds a barrel, to give a drink of very roughly 1060OG that must have been mid to dark brown in colour: the kind of brown ale that had vanished from London 30 to 40 years earlier. The ingredients for 43 hogsheads – 64.5 barrels – of stout a year earlier, January 1796, were 15 barrels of brown malt and 35 barrels of pale malt, 30 per cent brown, against the 40 per cent brown in the ale, and 273 pounds of hops, just under four pounds four ounces of hops per barrel, to give an OG of perhaps 1080 and considerably more bitterness, though a lighter colour, than the ale would have had. Indeed, Edward suggested that to get the colour in the stout that the customers would have wanted, Guinness was perhaps charring the inside of its casks. However, that’s another theory I don’t buy …

Sunday

Frank Clark himself kicked off Sunday morning, dressed in his finest green suit with knee breeches, as an 18th century brewer should be. His talk was on “Home Brewing in 18th Century Virginia: Some Interesting Things They Did With Beer”. I was rather worried by the repetition of the “water was unsafe to drink” meme, but apparently Williamsburg water really was unsafe. The town’s wells were contaminated by sewage, while the water table was only some 25 feet down, which meant that as Williamsburg was on a peninsula and the sea was just three miles away, they were also sometimes filled with salt water. Colonial Virginian home-brewers used molasses, with wheat bran or oat bran, presumably for flavour, and hops and there were a fair number of home brewers around: at least 80 households brewed when the town’s population was only about 1,800.

Next up was your not very humble blogger, talking about “Industrialisation in the British Brewing Industry 1720-1850: the Rise of the ‘Power-Loom Brewers'”. Charles Barclay of Barclay Perkins had called the big London porter breweries “power-loom brewers” in the 1830s, meaning they had taken up new technology in the form of steam engines and the like the way the cotton weavers of the North West of England had leapt to mechanise. But my thesis was that (1) the brewers had grown to enormous (for the time) size even before they mechanised and (2) they beat the “power loom weavers” to it, being among the very first manufacturers to adopt steam power.

Mitch Steele, brewmaster at Stone Brewing in California followed, his chosen subject being “The True Origins of India Pale Ale in England, Scotland and the United States”. Sound man, Mitch: I sat ready to heckle, but feeling confident I wouldn’t have to, and I was right. Right behind Mitch was Ron Pattinson, demonstrating his width of knowledge with something only he could have presented, “International Co-operation in the 19th Century Brewing Industry”. You can get an idea of his talk from this article in Beer Advocate here.

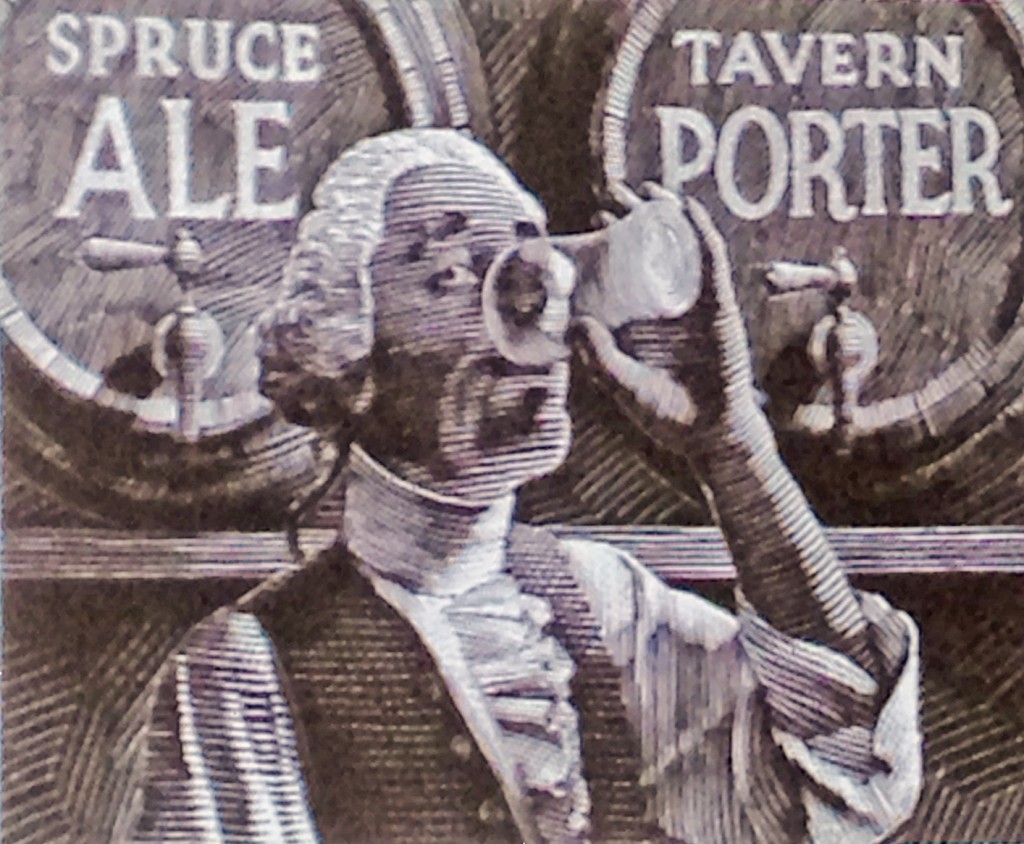

As we headed towards the finish, two more brewers gave terrific presentations. Tom Kehoe, founder of Yards Brewing Company in Philadelphia, spoke on “Brewing Historic Beers for a Modern Market”. Yards brews several beers with a historical theme, including General Washington’s Tavern Porter, Thomas Jefferson’s Tavern Ale and Poor Richard’s Tavern Spruce, a spruce beerbased on a recipe by Benjamin Franklin using barley molasses and essence of spruce. Then Tanya Brock, manager and brewster at the Carillon Brewery in Dayton, Ohio, revealed all on the running of a brewery dedicated to making only historic beers, The brewery, which opened in 2014, is part of the Carillon Historical Park, which was set up to showcase the history of Dayton, though its name comes from the 150-feet-tall carillon in the grounds, where concerts happen every week. At the brewery, meanwhile, Tanya and her team turn out historic brews including a sour porter – I SO want to go to Ohio– and a coriander ale from 1831. It was then down to the beer writer Randy Mosher to sum up with a talk on “The Past and Future Beer”, and for everybody to file out of the auditorium thinking: “That was great! I really hope Colonial Williamsburg do it again next year …”

I didn’t spend all my time in the conference hall, of course: the night I arrived I went out to the Alewerks Brewery’s taproom. I don’t believe – I’ll be corrected if I’m wrong – any new small American brewery would open now without having an on-site bar to sell its beers, but it’s still nothing like common enough in the UK. The Alewerks Tap was clearly a well-used, popular local bar that just happened to sell only one brewer’s beers, though with a dozen different ales, stouts porters and speciality brews to decide among, there was no demurring from me. The “soaking up the beer” problem was solved by the bar supplying half-pound soft petzels for the hungry: simple, cheap, effective, welcome.

The next night, after Randy Mosher had opened the conference and I had said hello to the surprising number of people I had met before, several car-loads of mixed speakers and conference attendees went off to Williamsburg’s newest brewery – so new, in fact, it wasn’t officially open – the Virginia Beer Company. It has been started by Robby Wiley and Chris Smith, two former graduates of William and Mary College in Williamsburg, (the second oldest university in the US, after Harvard) who had apparently made fortunes in the banking business despite only being in their 20s, and who had decided that running a brewery was just the tickety-boo. I was told that around $1.5m had been spent on the whole start-up, and it looked like it: lots of lovely shiny stainless-steel brewing kit (30-barrel capacity in the main set-up, five barrels in the experimental brewery) in a big tall-ceilinged former garage about a mile from the Colonial Williamsburg district. And, of course, there’s a tap: a huge drinking area, in fact, across the front of the old garage, with walls covered in wood from a barn dating from 1907 and room for more tables outside in the sun, all impressive. And the beers were good too.

Most of my between-lectures drinking was in the DoG Street Pub, DoG standing for Duke of Gloucester, and Duke of Gloucester Street being the main thoroughfare through Colonial Williamsburg (it was named for the son of the then Princess Anne, third in line to the throne while he was alive, whose death aged 11 in 1700, before his mother became Queen Anne in 1702, meant the British crown eventually passed to the Hanoverians). The building is a former bank converted in 2012, and the establishment styles itself as a “gastropub”. Not the smallest attraction was that it was relatively easy to find room for six or more people to sit at a table: Williamsburg being a tourist honeypot means that while the Colonial area has plenty of “taverns” where mob-capped wenches come round with stoneware mugs of ale, you’re likely to be told: “Can you come back in an hour, we’re full right now …” Bet they never said that to Thomas Jefferson and George Washington.

Also, the DoG Street Pub has an excellent selection of beer: the first time I went in I was able to try draught Gose from the Bahnhof brewery in Leipzig, Procrastinator Batch 2, an “accidental eisbock” brewed in 2014 by the Brasserie des Franches-Montagnes in Switzerland; and something called “Strawberry Schwarzcake”, a fruit-flavoured Schwarzbier from another Virginia brewery, Wild Wolf, in Nellysford, about 140 miles from Williamsburg. (Minor aside: I know this is a naïve cliché, but here’s a classic example of just how BIG the US is: 140 miles and we’re still in the same state. An equal distance from my house in London and I’m in Sheffield.) The food, too, stepped up to the plate (pause to wonder if that joke really works – OK, moving on …) the fish and chips was fine, though I passed on the corned beef and cabbage, since like most Britons of my generation, I’d be sure, “corned beef” means disgusting slices carved from a can of Fray Bentos and served with hard tomatoes, too-old lettuce and stale salad cream for a summer Sunday “salad”.

Then on the Sunday night we had what has to go down as the best “bring a bottle” party ever: Ron P, Chris “Arctic Ale” Bowen and I had been discussing bringing some old beers to Williamsburg, and that’s exactly what we did: I donated a Whitbread 1992 250th Anniversary Ale, a 1994 Thomas Hardy and a 1992 Courage RIS, Ron supplied two-decades-old Liefman’s Goudenband, Cantillon Rosé de Gambrinus and Hertog Jan Grande Prestige, and a 1930s Truman No 1 Barley Wine, while Chris brought some John Smiths nips from the 1950s, including a Coronation Ale from 1953. Around 20 people jammed into the hotel room in the Williamsburg Lodge of Ron’s friends Paul and Jamie Langlie to enjoy those and other gems that had been brought along, including an old bottle of Double Diamond (!), a 1988 John Lees Harvest Ale, an old Sierra Nevada Bigfoot Ale and a Bass 200 Ale from 1977. Astonishingly, all the beers were drinkable, and some verged on excellent.

Finally, before I left on the Monday, I went to see Frank Clark demonstrate colonial-style brewing: tremendous, especially the making of essentia binae, the burnt molasses colouring brewers used to make their porters as dark as possible before the invention of “patent” malt in 1817.

Many thanks to Colonial Williamsburg and everyone who works there for inviting me over and organising a truly excellent weekend, particular thanks to Frank Clark and his team for being such great hosts, cheers to everybody I met there, well done to everyone who bought my books in the bookstore, and let’s hope it happens again.

†Though Richmond, Virginia is named for Richmond, Surrey – which itself is named for Richmond, North Yorkshire, which was named for the village of Richemont in Normandy. Hampton, Virginia, however, is named for Southampton, not the one in Middlesex.

“The Romans taught the Celts and Germans: the last part, I have to say, I don’t believe at all.” Well, he Celts in what’s now Germany and southern France were making malts and brewing 500 BCE. Those two places are so far apart that malting and brewing must have begun much earlier. So given that the Roman Republic was founded in 509 BCE, well, that theory makes no sense. It makes even less sense when you know that proto-beer was found in Denmark dating from 700 years before the village of Rome was even founded.

“Archaeological finds, he said, show much of the earliest use of hops in the Baltic and North Sea areas, particularly around Bremen and Hamburg, taking the focus away from Southern Germany, which is normally given primacy in the use of hops in brewing, and giving it to the Vikings.” Yep, true. I’ve been planning to write about this. However, it may well be that the origin of hops lies further east and south, and that the archaeological evidence just hasn’t been dug up yet.

Karl-Ernst Behre’s ‘History of beer additives in Europe’ has some more modern successors like ‘Viking Age garden plants from southern Scandinavia’ (2012) by Permille Rohde, Ulla Lund Hansen, Sabine Karg. Fascinating research that leads me to say history was perhaps writen by the victors.

Behre’s paper was the definitive study, but like you say there’s been some very interesting finds after it. Hops have been found surprisingly early in Russia, Sweden as well as other places in Denmark. Some of these are not published in English, which is one reason I was thinking of doing a blog post.

Behre’s paper does have some strange omissions, though. He mentions Juniper in connection with Estonia, but doesn’t seem to realize it was used in Latvia, Finland, Sweden, and Norway, too, and that in Norway especially it was even more important than hops. (Did a check today. Of the 177 Norwegian farmhouse recipes I have, 90% use juniper.)

I greatly look forward to your write-up Lars. My money is still on the Chuvash as the inventors of hopped beers, but only for flavouring: I’d be fairly confident the discovery that beers could be peserved by boiling hops in wort was discovered hundreds of years after hops were first used to flavour beer

Was Frank using malted barley, Martyn? Or another grain? Did he mention if it was imported? I know Jefferson had a tough go of growing barley at Montecello, and barley didn’t—and doesn’t—grow well up here in New York. At least not 2-row, summer and spring varieties. It’s not a great growing environment. I would imagine Virginia to be even worse.

Prior to the 1760s wheat, oats, spelt, and rye were used (The mid-Hudson Valley and especially Central New York were major wheat growing centers prior to the Revolution, and the Schoharie Valley is known today as the “breadbasket of the Revolution”). Barley was used, but crops were inconsistent, and growers found it to be unprofitable. Bere/Bigg, 4-row, and 6-row winter variants were brought by the Scots in the mid 18th century, and grew fairly well. And although New York became a major grower of winter barley in the 1850s, it doesn’t really seem to have caught on until the turn of the 19th century—and even then New York has to deal with a Hessian Fly infestation, which compounds the growing problem. Even as late as the mid 1790s, a third of James Boyd’s grain purchases, here in Albany, were rye and wheat. I suspect they were being used as adjuncts—as supplements for times of weaker barley crop yields—but mixed grain grists may simply have been preferred as well.

Dutch culture was still very prevalent in New York at the end of the 18th century (and well in the 19th century too). The older style, non-barley beer (which I presume to be more bitter as it is often referred to as beer rather than ale) may have still been quite popular. I often refer to the period between the end of the Revolution and say the War of 1812, as the “Transition Period” as it was both a shift from wheat beer to barley ale, and a Dutch to Anglo-American culture in the Hudson valley.

No idea, there were too many “ordinary” tourists in the scullery when he was brewing to grill him – you’ll have to ask him yourself …

Any chance you can provide more details on the old beers that were opened? A 1930s barley wine? Something like that shouldn’t be drunk without a few words remembering what it was like.

Mate, it was 11pm, the room was crowded with people eager to get even a tiny sip of these beers … no.

It’s great fun watching Frank brew on that old kit. I even got to do some mash stirring. And thankfully ordinary tourists weren’t allowed in during our brewing session.

[…] Cornell notes here, the event price was $325 not including travel and lodging, and still it attracted more than 120 […]

[…] a sua volta attraverso l’indefessa e impagabile opera di pubblicistica birraria svolta da Martyn Cornell – che ci siamo trovati di fronte a un panorama pullulante, come detto, di spunti conoscitivi […]