Spruce beer is made from the tips of spruce trees. Except that the connection is not as simple as it appears: it is pretty much a coincidence that spruce beer and spruce trees have the same name.

There are actually two traditions of spruce beer in Britain: the older, the Danzig or Black Beer tradition, only died out very recently, while the other, which could be called the “North American tradition”, was hugely popular in Regency times, and included Jane Austen among its fans, but disappeared nearly 200 years ago on this side of the Atlantic.

The first mention of “spruce beer” in English is from around 1500, when Henry VII was on the throne, in a poem called Colyn Blowbolles Testament, in which a hung-over drunkard is persuaded to write his will. Colyn lists the drinks he wants served at his funeral, including more than a dozen types of wine, mead, “stronge ale bruen in fattes and in tonnes”, “Sengle bere, and othir that is dwobile”, and also “Spruce beer, and the beer of Hambur [Hamburg]/Whiche makyth oft tymes men to stambur.”

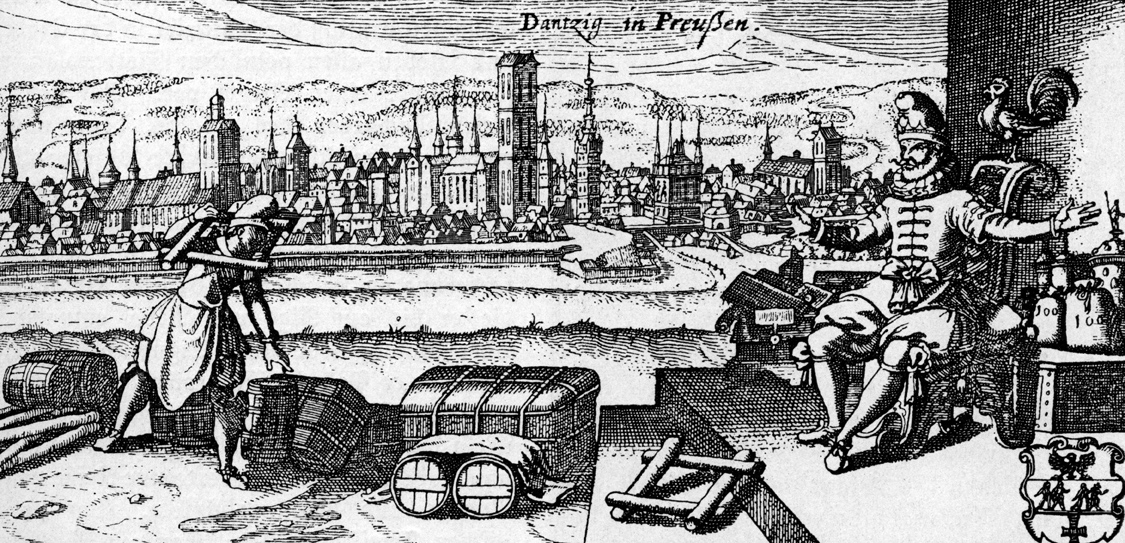

The fact that spruce beer and “the beer of Hambur[g]” were mentioned together is because both came from North Germany. The name “spruce beer” is an alteration of the German “Sprossen-bier”, literally “sprouts beer”, more meaningfully “leaf-bud beer”, since it was flavoured with the leaf-buds or new sprouts of Norway spruce, Picea abies, or silver fir, Abies alba. “Sprossen” was meaningless to English-speakers, but in early modern English the similar-sounding “Spruce” was another name for Prussia, from which country’s main port, Danzig, Sprossen-bier was exported. “Sprossen-bier” became in English the more understandable “Spruce beer”, meaning, originally, “Prussian beer”. (Chaucer called the country “Sprewse”, and it was being called “Spruce-land” as late as 1639.)

Meanwhile English had to wait more than a century and a half after the beer was named to get its own word for Picea abies, the tree known as Fichte in German and gran in Norwegian. When the tree did get an English name, first mentioned by the naturalist John Evelyn in 1670, because it, too, like the beer, came to Britain via Prussia, it was called the “Spruce”, short for “Spruce fir”, that is, “Prussian fir”. Thus “spruce beer” is not actually named for the spruce tree, and “spruce beer” in English is around 170 years older as a phrase than “spruce tree”. (The adjective “spruce” meaning “neat” or “smartly dressed” probably also comes from “Spruce” meaning Prussia, via “Spruce leather”, leather from Prussia that was a favourite, it appears, among Tudor dandies.)

“Sprossen-bier” was also called in German “Danziger bier” or “Joppenbier”. The German physician Jacob Theodor von Bergzabern, better known by his Latinised name, Tabernaemontanus, raved about it in his Neuwe Kreuterbuch (“New Book of Herbs”), published in 1588, declaring that there were “many sorts of good and hearty beers” made in the land of the Prussians, but Danzig beer, or Joppenbier, “takes the prize … there is in a little beaker of this beer more strength and nourishment, than in an entire large mug of ordinary beer.” Joppenbier, he said, was a beautiful reddish-brown colour and “thick like a syrup”, and it strengthened the blood and gave a “lovely colour” to those who drank.

“Danziger Jopen-bier” was still going in 1946, when it was described by a Czech professor in a lecture to a group of English brewers as “one of the most interesting and unique of top fermented beverages”. It was made by boiling wort for up to ten hours until it reached a gravity of between 45 and 55 per cent Balling – a stupefying 1200 to 1260 OG or so. The wort was then run into wooden vessels and fermentation undertaken by a “mixed microflora” of moulds and yeasts present in the wood, with other yeasts joining in as fermentation progressed. The final beer was only 2.5 per cent to 7 per cent alcohol, with an acidity (as lactic acid) of 1 to 2 per cent. The name “Jopen”, the professor claimed, was “derived primarily from a word meaning a large mug out of which beer is consumed”, which, given that Tabernaemontanus said you only needed a “Tafelbeckerlein”, a little beaker, of Joppenbier to get more benefit than from a “Maß” of ordinary deer, seems dubious. But the beer described in 1946 must have been considerably sweet, and very dark, and was clearly the same as the “Dantzig spruce or black beer” described by a writer in 1801 as one of the beers that were “only half fermented”. A decoction of spruce buds or cones was added to the wort before fermentation, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica in 1890. However, a description of making Joppenbeer in German from 1865 fails to mention spruce:

“Danziger Jopen-bier” was still going in 1946, when it was described by a Czech professor in a lecture to a group of English brewers as “one of the most interesting and unique of top fermented beverages”. It was made by boiling wort for up to ten hours until it reached a gravity of between 45 and 55 per cent Balling – a stupefying 1200 to 1260 OG or so. The wort was then run into wooden vessels and fermentation undertaken by a “mixed microflora” of moulds and yeasts present in the wood, with other yeasts joining in as fermentation progressed. The final beer was only 2.5 per cent to 7 per cent alcohol, with an acidity (as lactic acid) of 1 to 2 per cent. The name “Jopen”, the professor claimed, was “derived primarily from a word meaning a large mug out of which beer is consumed”, which, given that Tabernaemontanus said you only needed a “Tafelbeckerlein”, a little beaker, of Joppenbier to get more benefit than from a “Maß” of ordinary deer, seems dubious. But the beer described in 1946 must have been considerably sweet, and very dark, and was clearly the same as the “Dantzig spruce or black beer” described by a writer in 1801 as one of the beers that were “only half fermented”. A decoction of spruce buds or cones was added to the wort before fermentation, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica in 1890. However, a description of making Joppenbeer in German from 1865 fails to mention spruce:

Danziger Joppenbier

Joppenbier is in many respects very interesting. It is made from a highly concentrated wort – the Saccharometer degree is about 49 per cent. From 1000 Kg malt and 5 Kg hops approximately 10.5 hectolitres of beer is produced. The mash is made by the infusion method and the wort which is drawn off is – to obtain the specified concentration – often boiled more than 20 hours. The wort is cooled down to down to 12.5 degrees.

The fermentation is a so-called spontaneous fermentation. Fermentation usually begins in July – although it is the same whether the beer is brewed in January or April. The wort is first covered with a thick blanket greenish-white mould; when the mould spores are in sufficient quantity to force their way into the wort and to grow to a very characteristic yeast, then the fermentation begins, which only in September subsides enough so that the beer becomes clear and can be drawn off. The attenuation is during this period up to only about 19.

The resulting beer is dark brown and extremely rich (partly from un-broken-down glucose) and sweet. The smell is pleasant (which is probably a consequence of the extremely slow fermentation). It is not possible to drink much Joppenbier – it is full-bodied, extremely suitable for mixing with other beer and is exported to England for this purpose. The clear beer can be left a year in the vat on the yeast without being damaged – of course, however, the degree of attenuation will increase.”

When the Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz set off on his third voyage around the top of Norway and Russia in 1596 to try to find the Northeast Passage from Europe to China, he and his team took with them casks of beer that included at least one barrel of “iopen”, which is specifically called in the Latin version of the account of what turned out to be Barentsz’s last voyage “cerevisia dantiscana” – Danzig beer. Barentsz’s crew were stranded on Novaya Zemla in the Arctic Ocean, just 900 miles from the North Pole, over the winter of 1596/7, when it became so cold that the “iopen” froze, bursting its cask. The crew tried to drink the beer as it thawed, but they had inadvertently invented freeze-distillation, with the alcohol unfreezing first, and “it was too strong to drinke alone”. (That “cerevisia dantiscana” was a synonym for the beer also known as “Joppenbier” and “Preusing” – “Prussian” in Old Danish – is confirmed in a book written in Latin by a German author in 1722 listing the names of all known drinks, though confusingly it also translates “Cerevisia Batavorum”, “Batavian” or Netherlands beer, as “Joppen-Bier”: Dutch joppenbier appears to be an entirely different tradition.)

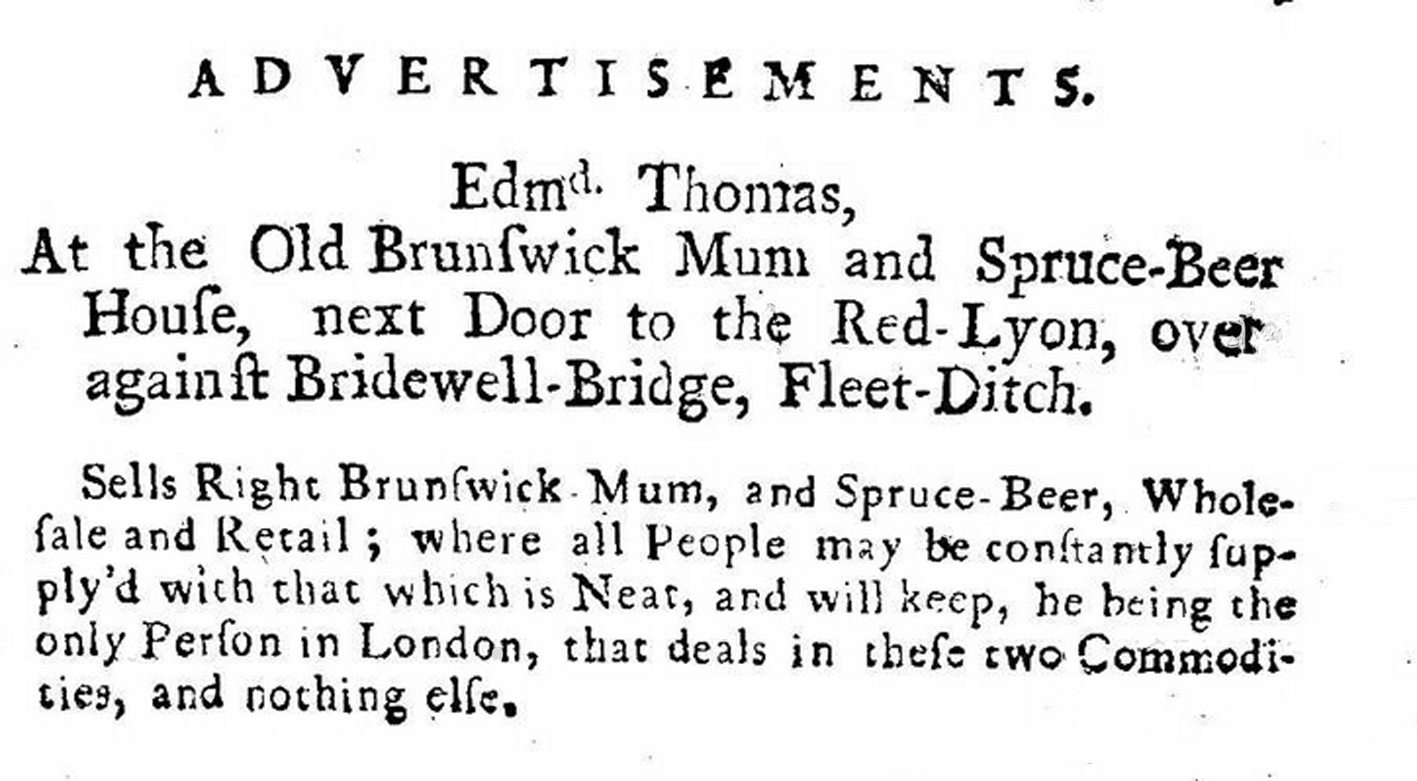

Spruce beer looks to go underground in Britain after Colyn Blowbolle in the time of the Tudors, with only a couple of glimpses in the next two centuries. A writer in 1832 claimed that in 1664 an advertisement appeared in London declaring: “At the ‘Angel and Sun,’ in the Strand, near Strand Bridge, is to be sold every day, fresh Epsum-water, Barnet-water, and Tunbridge-water; Epsum-ale, and Spruce-beer.” By 1719 the “Old Brunswick Mum and Spruce Beer House” was open “next door to the Red-Lyon, over against Bridewell-Bridge, Fleet-Ditch” in London, and selling “right Brunswick-Mum, and Spruce-Beer, Wholesale and Retail”, with the proprietor, Edmund Thomas, claiming to be “the only person in London that deals in these two commodities, and nothing else.” (It was still open in April 1757, when “a large parcel of Mum” had just been imported.)

These establishments were both almost certainly selling Danzig-brewed spruce beer, and from 1720 onwards newspapers began regularly recording kegs of spruce beer or black beer from Danzig, in quantities of up to 200 kegs at a time, among the huge range of goods from around the world being imported into Britain, from lime juice out of Jamaica to iron from Sweden, with the kegs arriving in ports from London to Newcastle upon Tyne. The kegs apparently held two gallons each, and the retail price was a high eight shillings and sixpence a cask, or more than six pence a pint, when porter was three pence a quart. Part of the high cost was the duty paid: £2 per 32-gallon (wine measure) barrel, when ordinary strong beer paid only 10s.

These establishments were both almost certainly selling Danzig-brewed spruce beer, and from 1720 onwards newspapers began regularly recording kegs of spruce beer or black beer from Danzig, in quantities of up to 200 kegs at a time, among the huge range of goods from around the world being imported into Britain, from lime juice out of Jamaica to iron from Sweden, with the kegs arriving in ports from London to Newcastle upon Tyne. The kegs apparently held two gallons each, and the retail price was a high eight shillings and sixpence a cask, or more than six pence a pint, when porter was three pence a quart. Part of the high cost was the duty paid: £2 per 32-gallon (wine measure) barrel, when ordinary strong beer paid only 10s.

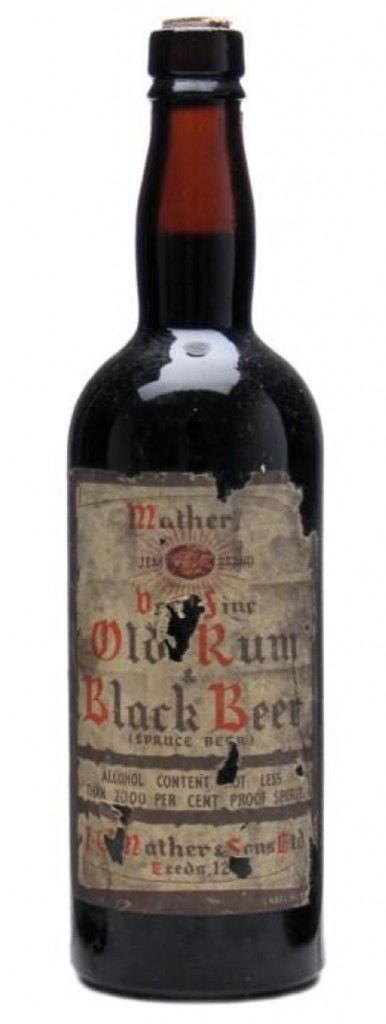

As the 19th century continued, spruce or black beer continued to be imported from Danzig to Great Britain: 24,950 kegs arrived in 1829, for example, 98 per cent of all the spruce beer the city exported that year, at 6s 6d a keg, worth £8,108 15s. it was on sale in London in 1850 for 1s 3d for a quart bottle, or 10s 6d a keg. Import duties on spruce beer brought in £3,015 in the 12 months to 31 March 1859 (for comparison, excise duty on wine in the same period totalled £1.76 million). The following year, 1860, Danzig exported spruce beer worth 86,500 thaler, or just under £13,000, perhaps £1 million today. Much of the time it must have been drunk for its supposed health-giving properties: an Australian newspaper in 1843 reported: “Infallible Cure For Colds: Two tablespoonsful of Dantzic black beer, taken with hot water, sugar, and about half-a-glass of old rum, or malt whisky; immediately before going to bed, is said to cure the most obstinate and long-standing colds, and has succeeded where every other remedy failed.”

As the 19th century continued, spruce or black beer continued to be imported from Danzig to Great Britain: 24,950 kegs arrived in 1829, for example, 98 per cent of all the spruce beer the city exported that year, at 6s 6d a keg, worth £8,108 15s. it was on sale in London in 1850 for 1s 3d for a quart bottle, or 10s 6d a keg. Import duties on spruce beer brought in £3,015 in the 12 months to 31 March 1859 (for comparison, excise duty on wine in the same period totalled £1.76 million). The following year, 1860, Danzig exported spruce beer worth 86,500 thaler, or just under £13,000, perhaps £1 million today. Much of the time it must have been drunk for its supposed health-giving properties: an Australian newspaper in 1843 reported: “Infallible Cure For Colds: Two tablespoonsful of Dantzic black beer, taken with hot water, sugar, and about half-a-glass of old rum, or malt whisky; immediately before going to bed, is said to cure the most obstinate and long-standing colds, and has succeeded where every other remedy failed.”

By the early 19th century, British firms, almost all in the North of England, had started making black beer themselves, to the same specifications as the Danzig version. One of the first known is R Barnby of Hull, “black beer manufacturer”, who went bankrupt early in 1815. Six years later, in 1821, another Hull-based black beer brewer, J Roberts, also went bankrupt. Leeds had four black beer brewers listed in 1823, though three brewed other beers as well, and Huddersfield one. Pigot’s directory of Hull in 1828 listed five “black beer brewers and importers” in the port. Sheffield had one black beer brewer the same year, Francis Parker of Trippet Lane, who also brewed ale and porter. By 1837 Leeds had six black beer brewers listed, plus one importer, while Huddersfield the same year had two black beer brewers. (Despite black beer being far more popular in the North, Dickens has the Magpie and Stump public house in Clare Market, London, advertising “Devonshire cyder and Dantzic spruce” on printed cards in the windows in The Pickwick Papers, published first in 1836). A later Leeds black beer brewer was the Cambria Vinegar Company, which was primarily a vinegar brewer based in Elland Road, Leeds, but which also supplied fish and chip shops with other essentials such as oil for their fryers. Among those in Sheffield was John Wheatley of the Dantzig Brewery, Division Street, who appears in a directory of 1862 and was advertising himself three years later as “black beer brewers and manufacturers of peppermint and raspberry cordials, aerated ginger beer, lemonade, soda water, lithia and German seltzer waters, agents for Messers Hoare and Co’s London Porter and Stout”.

By the early 19th century, British firms, almost all in the North of England, had started making black beer themselves, to the same specifications as the Danzig version. One of the first known is R Barnby of Hull, “black beer manufacturer”, who went bankrupt early in 1815. Six years later, in 1821, another Hull-based black beer brewer, J Roberts, also went bankrupt. Leeds had four black beer brewers listed in 1823, though three brewed other beers as well, and Huddersfield one. Pigot’s directory of Hull in 1828 listed five “black beer brewers and importers” in the port. Sheffield had one black beer brewer the same year, Francis Parker of Trippet Lane, who also brewed ale and porter. By 1837 Leeds had six black beer brewers listed, plus one importer, while Huddersfield the same year had two black beer brewers. (Despite black beer being far more popular in the North, Dickens has the Magpie and Stump public house in Clare Market, London, advertising “Devonshire cyder and Dantzic spruce” on printed cards in the windows in The Pickwick Papers, published first in 1836). A later Leeds black beer brewer was the Cambria Vinegar Company, which was primarily a vinegar brewer based in Elland Road, Leeds, but which also supplied fish and chip shops with other essentials such as oil for their fryers. Among those in Sheffield was John Wheatley of the Dantzig Brewery, Division Street, who appears in a directory of 1862 and was advertising himself three years later as “black beer brewers and manufacturers of peppermint and raspberry cordials, aerated ginger beer, lemonade, soda water, lithia and German seltzer waters, agents for Messers Hoare and Co’s London Porter and Stout”.

Spruce beer imports from Danzig began to fall, with the total excise duty collected in 1868 down to £1,756. (The duty collected on essence of spruce for that year was just £1.) All the same Britain still imported 398,449 litres of spruce beer from Danzig in 1877, about 28,100 kegs, at 8s 6d per keg FOB, totalling just under £12,000, and 99 per cent of the total exported from the city. One Danzig-based spruce beer (and lager) brewer, Robert Fischer, whose “best Danzig black beer” was being imported into Newcastle upon Tyne in 1855, still had an agency in Glasgow in 1886, according to the Post Office Directory that year, and spruce beer was coming “direct from Hamburg” in 1897, “the best and strongest”.

By the 20th century black beer manufacturers in Britain were concentrating on the healthy aspects of the drink. W Severn & Co of Curzon Street, Derby, said its Black Spruce Beer, 5s 5d for a large bottle in 1922, “will keep indefinitely … fortifies the system against Chills, Colds and Weakness as nothing else can … invaluable for growing children.” Another Derby-based black beer brewer, Burrows & Sturgess Ltd of the Spa Works, revealed some of the secrets of the drink’s making in an advertisement from 1920, saying that black beer, “also known as Spruce Beer” was “a strong heavy liquid, very dark in color [sic], and is produced chiefly from Malt, blended with Dantzic Spruce. After evaporation and fermentation the Beer should mature for over twelve months before being offered for sale. Owing to its dense gravity, and being a fermented product of Malt, it pays a heavy Excise duty, but its great medicinal value being recognised, it is not classed as an ordinary beverage, and its sale is free from restrictions. It has a decidedly pleasant and piquant flavour, which appeals to most people. It is of the greatest value as a preventative and remedy for Coughs, Colds, Influenza and Weakness. It is the 100% Food Tonic. It may be taken alone, or with the addition of hot water, sugar and spirits. It is fully matured, will keep indefinitely and if of the heaviest gravity. No house should be without a bottle of this wholesome and beneficial Beer. For growing children it has no equal. Supplied in bottles (six-to-gallon size) 6s 3d per bottle.”

By the 20th century black beer manufacturers in Britain were concentrating on the healthy aspects of the drink. W Severn & Co of Curzon Street, Derby, said its Black Spruce Beer, 5s 5d for a large bottle in 1922, “will keep indefinitely … fortifies the system against Chills, Colds and Weakness as nothing else can … invaluable for growing children.” Another Derby-based black beer brewer, Burrows & Sturgess Ltd of the Spa Works, revealed some of the secrets of the drink’s making in an advertisement from 1920, saying that black beer, “also known as Spruce Beer” was “a strong heavy liquid, very dark in color [sic], and is produced chiefly from Malt, blended with Dantzic Spruce. After evaporation and fermentation the Beer should mature for over twelve months before being offered for sale. Owing to its dense gravity, and being a fermented product of Malt, it pays a heavy Excise duty, but its great medicinal value being recognised, it is not classed as an ordinary beverage, and its sale is free from restrictions. It has a decidedly pleasant and piquant flavour, which appeals to most people. It is of the greatest value as a preventative and remedy for Coughs, Colds, Influenza and Weakness. It is the 100% Food Tonic. It may be taken alone, or with the addition of hot water, sugar and spirits. It is fully matured, will keep indefinitely and if of the heaviest gravity. No house should be without a bottle of this wholesome and beneficial Beer. For growing children it has no equal. Supplied in bottles (six-to-gallon size) 6s 3d per bottle.”

One manufacturer, Joseph Hobson & Son (which also called its premises, in The Calls, Leeds the

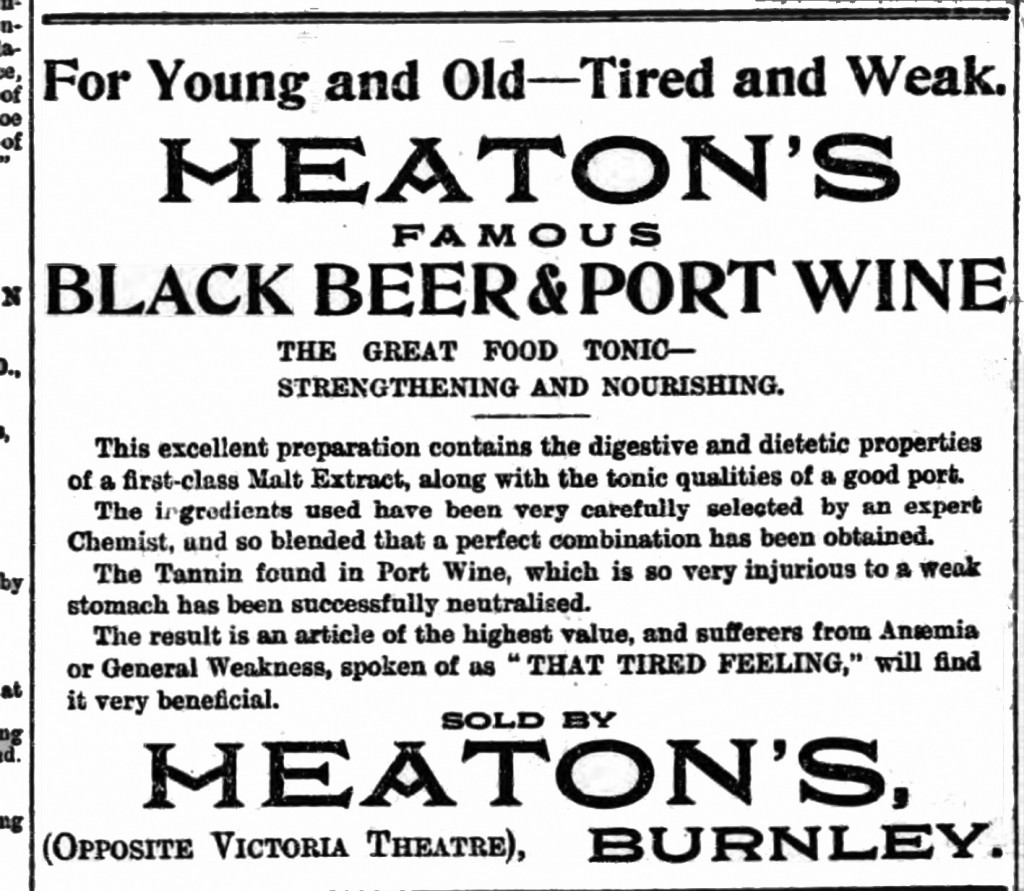

One manufacturer, Joseph Hobson & Son (which also called its premises, in The Calls, Leeds the Dantzig Dantzic brewery, and which claimed to have been in existence for over a century in 1931), declared that its black beer, “taken regularly, will prevent influenza.” (To be fair, it was estimated in 2011 that 30ml of black beer provided 25 per cent of the recommended daily allowance of vitamin C.) Different firms combined black beer with one or another alcoholic drink also promoted, at the time, as “good” for the run-down, so that Heaton’s of Burnley in 1906 sold “Famous Black Beer and Port, The Great Food Tonic – Strengthening and Nourishing”, with the tannin in the port, “so very injurious to a weak stomach, successfully neutralised”.

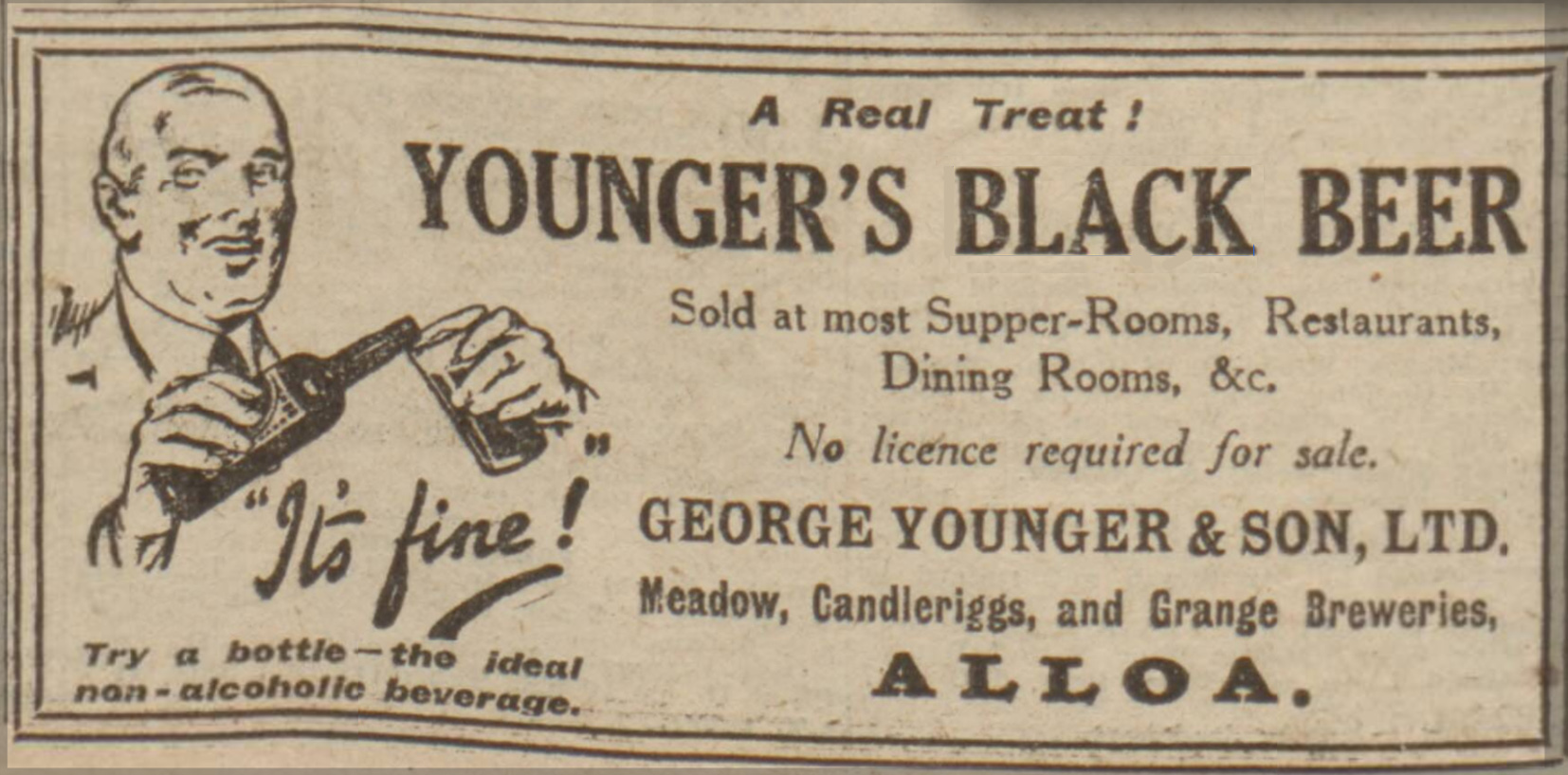

A rival Burnley firm sold Hartley’s Black Beer and Raisin Wine, “the Finest Black Beer and the Choicest Raisin Wine skilfully combined in exactly correct proportions … a Magnificent Tonic and Restorative for the Pale and Delicate … 1s per full-sized wine bottle.” Another supplier, A Greaves & Son Ltd, Chemists, The Market Place, Chesterfield, claimed in 1936 to have “The Tonic you have all beer waiting for! Black Beer and Australian Red Wine, only 1s 6d a big flask”. The makers of the rival Friar Brand black beer and red wine, sole agents DM Forbes of Chesterfield, said it was “invaluable for anaemic girls and all who are run-down”, and just 2s 6d a large bottle. At least one Scottish “mainstream” brewer, George Younger’s of Alloa, was making black beer in the 1920s, describing it as “non-excisable” – meaning it could be sold without a magistrates’ licence – and “so refreshing”.

The whopping original gravity of black beer, however, at 1200 or more, was nearly its death in the First World War, when the tax on beer, which was based on OGs, went up to almost 13 times the pre-war level by 1920, leading to excise rates on “mum, spruce or black beer” (the taxman still remembered Brunswick mum, if everybody else had forgotten) more than five times higher than on regular beers, at £26 2s a 36-gallon barrel. This was something which “almost destroyed” the industry, but Leeds-based MPs managed to get a tax rebate for black beer in 1923, which rebate was increased in 1924. When another massive increase in British beer tax was made in 1931, Yorkshire’s MPs succeeded in getting black beer finally exempted from tax completely, to ensure its survival. Its continued existence was helped by the fact that, despite an alcohol content of around 8.5 per cent by volume, no magistrates’ licence was required to sell it, and in 1929 it was said to be “largely sold by chemists”. (The continued inclusion of “mum” in the excise regulations confused MPs during the parliamentary debate on the budget, and the Liberal MP Ernest Brown had to explain, inaccurately, that “mum” was “similar not only to black beer, but also Berlin white beer”.)

The whopping original gravity of black beer, however, at 1200 or more, was nearly its death in the First World War, when the tax on beer, which was based on OGs, went up to almost 13 times the pre-war level by 1920, leading to excise rates on “mum, spruce or black beer” (the taxman still remembered Brunswick mum, if everybody else had forgotten) more than five times higher than on regular beers, at £26 2s a 36-gallon barrel. This was something which “almost destroyed” the industry, but Leeds-based MPs managed to get a tax rebate for black beer in 1923, which rebate was increased in 1924. When another massive increase in British beer tax was made in 1931, Yorkshire’s MPs succeeded in getting black beer finally exempted from tax completely, to ensure its survival. Its continued existence was helped by the fact that, despite an alcohol content of around 8.5 per cent by volume, no magistrates’ licence was required to sell it, and in 1929 it was said to be “largely sold by chemists”. (The continued inclusion of “mum” in the excise regulations confused MPs during the parliamentary debate on the budget, and the Liberal MP Ernest Brown had to explain, inaccurately, that “mum” was “similar not only to black beer, but also Berlin white beer”.)

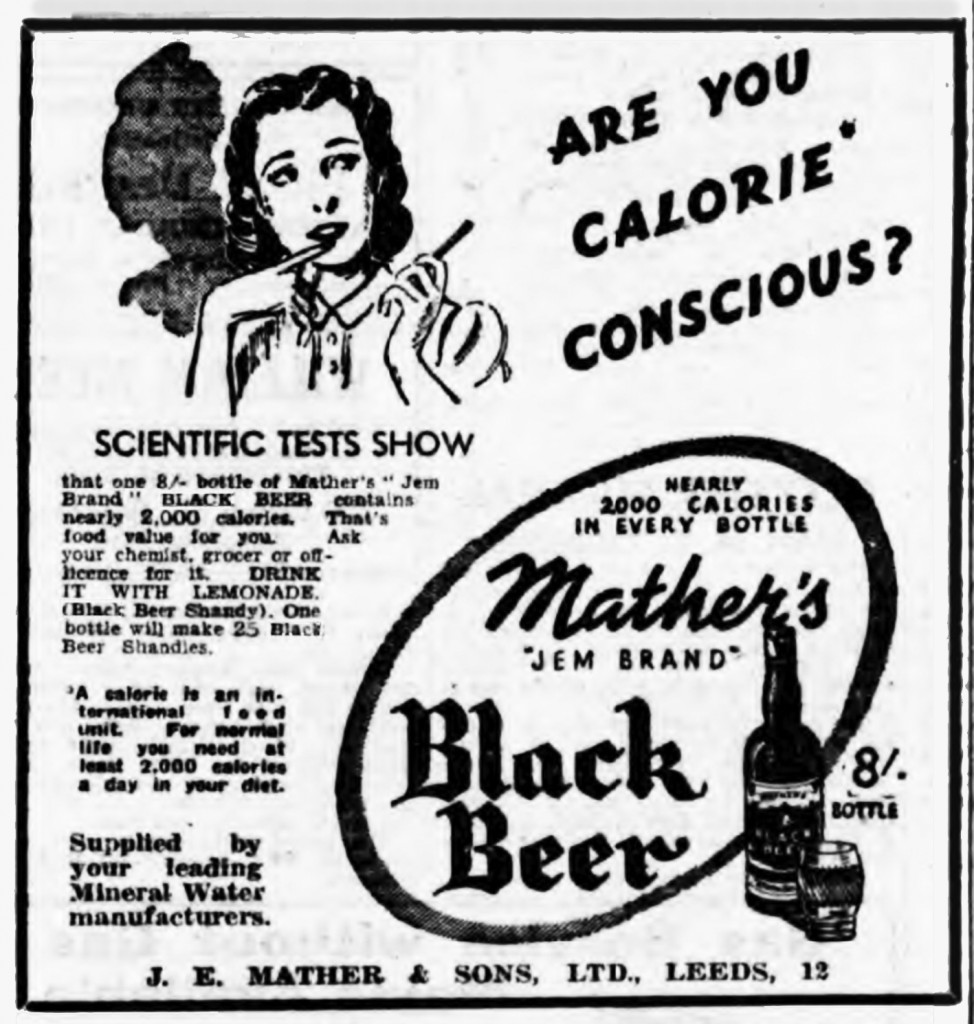

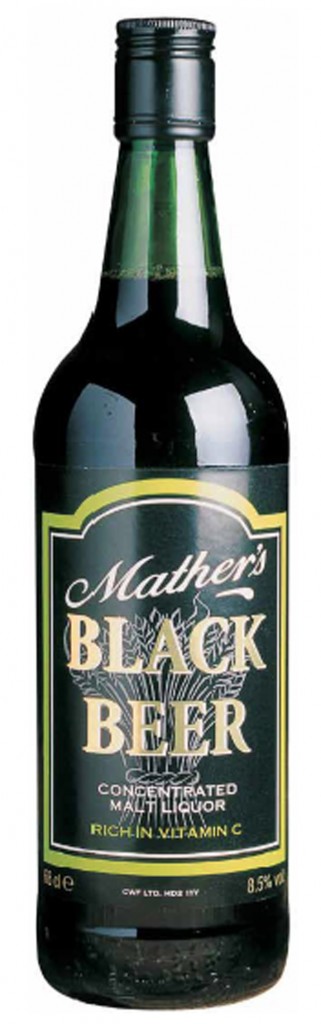

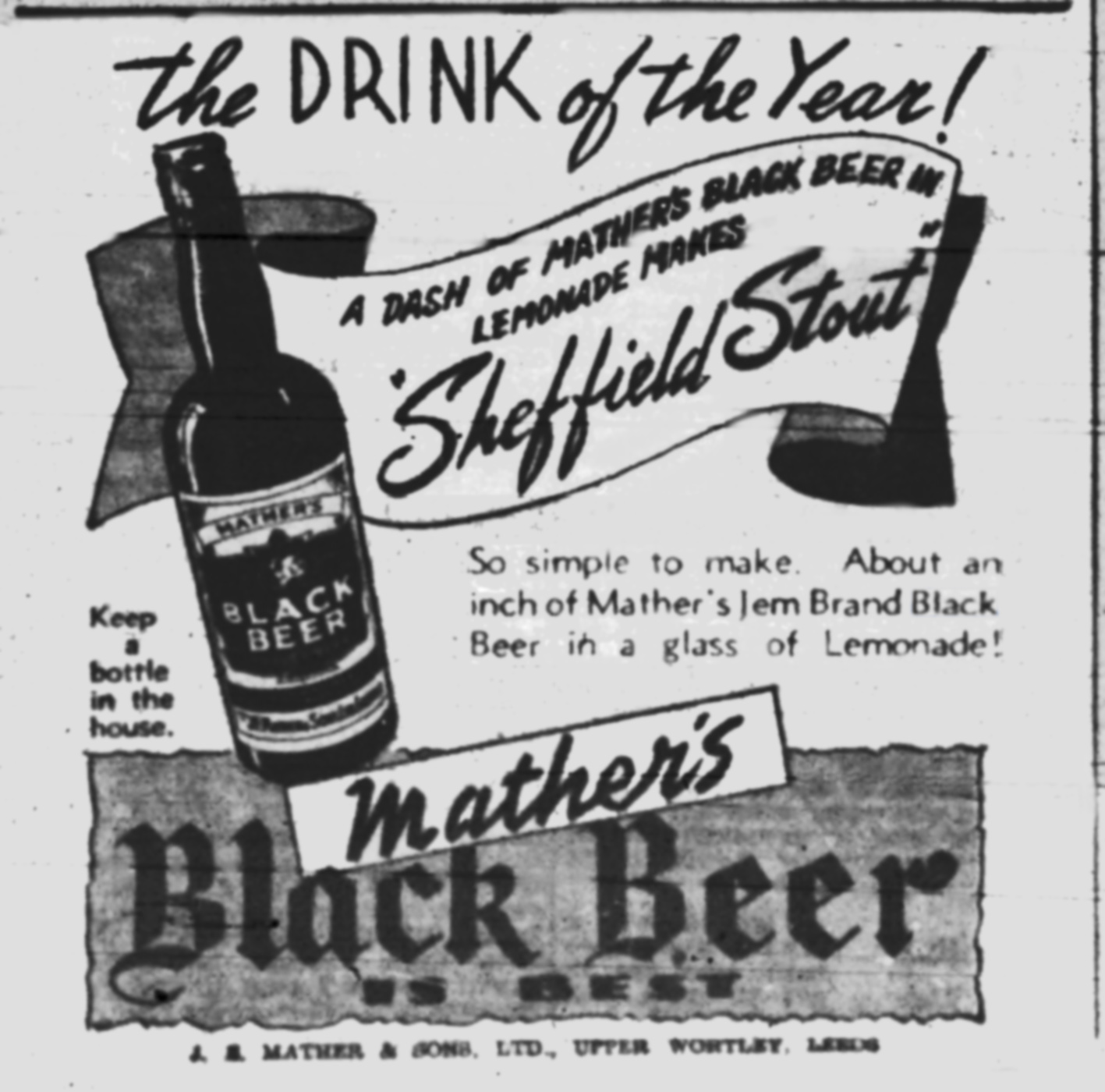

Hobson’s, which at one point had made “Danzovia” tonic wine, was still listing its “Hobson’s Choice” and “Spruce” brand black beers in 1969 but soon afterward merged with the wine and spirit merchant Gale Lister, leaving another Leeds firm, JE Mather & Sons, founded in 1903, as the only surviving maker of black beer in the UK. In 1950 Mather’s had been boasting that its bottles contained nearly 2,000 calories each, and recommending that purchasers mix it with lemonade to make a black beer shandy – known as a Sheffield stout. By 1992 the brand was owned by the drinks company Matthew Clark & Son, which successfully fought off a proposed imposition of a tax increase that would have doubled the price. In 1995 Matthew Clark closed its Leeds winery, but sold the brand to Continental Wine and Foods of Huddersfield, which continued to make Mather’s Black Beer. However, in 2012, as part of changes to the tax system, it was announced that the relief black beer had enjoyed since 1931 was to end the following year, which would mean the price of a 68cl bottle almost doubling to £4. Continental Wine and Foods was only selling 35,000 bottles a year, and in 2013 it ceased all production of black beer, saying the likely effect of the price rise on sales among the largely elderly buyers of Mather’s Black Beer meant it was not worth continuing with the product.

For part two of this history of spruce beer, the North American connection, click here

Excellent! Thoughts from another branch of the Hanseatic fan club. I have seen a definition that says Dutch for “shoots” is joopen. But would need to confirm its a Renaissance usage, too. And the beer early on might have skipped, transhipped from the eastern Hanseatic ports in the 1400s via the Netherlands so there may be overlap. Also, the importation of Hanseatic lumber would have seen the adjective for spruce likely show up in England’s Hanseatic licensed ports before 1400 along with the beer even if the beer was not for sale, but just for staff use. The beer and the lumber ought to have been two nouns with a similar adjective. 35 years ago an exchange student on my fitba team from Sweden showed us how spruce tips could be eaten just as they break from their brown paper covering. I was wondering if spruce is not just the one fir with shoots (as they all do) but the one known for its shoots because they are edible. Like the “Right” Whale being the right one for oil.

“I have seen a definition that says Dutch for “shoots” is joopen.”

Yes, I saw that, too, but ignored it as I couldn’t confirm it: the evidence I have seen suggests the Dutch and German jopen/joppen/joopen beers are different traditions …

Hi Martyn,

Don’t know about your evidence, but as far as I know the trade from Danzig (called the ‘Mother of Trades’) was dominated by Dutch ships. Probably because taxes on Jopen beer were so high, it was also made in various parts of the Netherlands. Also don’t know what you mean by ‘German’, but Jopen became a beer-style and could come from Danzig, but was also made in the Netherlands, like in Dordrecht, Deventer and Zwolle: oprecht en goet Jopen-Bier.

Frederik

Could be two different things (or more) at different places and times. There are four “cream ales” from 1800 to now.

The killing off of black beer was a shocking act of cultural vandalism.

I had no idea it was out there – and right up until 2012, too. Gone, and never called me mother.

If it survived until 2012, I’m a bit surprised it didn’t managed to claw its way out of the grave… the modern craft-beer movement is generally creating a lot more interest in unusual beers like this…

Yes, looking forward to an imperial white black beer! 😉

[…] read an interesting post recently on spruce beer. There were variants that were brewed using parts of spruce trees and others that may have drawn on […]

[…] For a history of the Spruce Beer, check out this fascinating post: https://zythophile.co.uk/2016/04/20/a-short-history-of-spruce-beer-part-one-the-danzig-connection/ […]

A very enjoyable and informative article! However, I must be churlish and point out that Hobson’s brewed at the Dantzic, not Dantzig brewery. Somewhere in my house I have slides of the brewery building taken in 1974 showing this and also two advertisements for two other Hobson’s products, Johnny Pine and Vint-Egg.

Thank you, Tony, corrections always very welcome.

Hi Martin,

Thanks for your reply. I’ve just realised that it was Gale Lister who lived in Calls Lane. Hobsons were in Eastgate.

Cheers, Tony

Gale, Lister & Co Leeds, anybody any info on this company? – thanks

This is important article, our best foods in bygone are brewed and harvested through distillation for essence, we are losing our arts only to necessitate relearning, oh what a sorry bunch of nanny staters have we nigh all become albeit through bank driven school conditioning rendering our psyche inert in traditional terms of application of self. Thank you.

[…] then being imported to Britain from northern Germany, according to the brewing historian and writer Martyn Cornell. Spruce or “spruse” originally meant “from Prussia.” Back in that era, spruce was probably […]

[…] some etymological fun. The term “spruce beer” showed up in the English language somewhere around 1500, and it was originally in reference to a […]

Readers may be interested to know Dantzic Beer is mentioned towards the end of Chapter VII in George Eliot’s Mill on the Floss (1860), as enjoyed by the Prussians who fought at Waterloo (1815).

Thank you for that, John, one George Eliot book I haven’t read – will now hve to do so …

[…] Eddy’s Spruce soda and/or spruce beer is a botanic foodie delight in the Great North. It settles the stomach and cures the snow-heave […]