Brakspear’s Triple is a regular on the Zythophile shopping list: not just because I try to support old fermentation methods, it’s a very tasty beer, marvellously fruity, toffee apples, peardrops and bananas, hints of fruitcake, sweet and bitter in perfect balance, a long and lingering tart, very dry finish, and remarkably light-footed for a beer of 7.2 per cent abv. It ages to an interesting state as well: I tried an 18-month old version at the weekend, sour tartness was coming through much more, which I’m not certain is meant to be there, but it was very pleasing regardless.

The beer gets its name partly because it is hopped three times, and also, and more relevantly, because it undergoes, effectively, a triple fermentation, two at the brewery, using what its brewers call the “double drop” system, and one in the bottle.

Brakspear’s in Henley, Oxfordshire was about the last brewery in Britain to use what most brewers call the “dropping” system of fermentation, (rather than “double drop”); the fermenting wort is “dropped” after 12 or 16 hours from the initial fermentation tun into another vessel below to continue and finish its fermentation, leaving the unwanted “gick” produced in the early part of the fermentation behind. When Refresh, then owner of the Wychwood brewery, purchased the right to brew Brakspear’s beers after the Henley brewery closed, it moved all the “dropping” equipment from Henley to Wychwood’s site in Witney, Oxfordshire.

However, although nobody else, or almost nobody, as far as I am aware, still regularly uses the “dropping” method to brew beers in Britain, it was once wide- spread. As the brewing scientist Charles Bamforth has commented, the existence of several different technologies for trying to achieve the same end is an indication that none of them is perfect. One of the important processes any brewer has to perform is to remove the excess yeast from his fermenting beer, and Victorian brewers used at least six different methods to achieve this. The Victorian journalist Alfred Barnard, in his four-volume Noted Breweries of Great Britain & Ireland, published 1889/91, described four of them, saying that while Burton used unions, Yorkshire the stone square and London and the South the skimming system, the beer was finished “in the East of England by the dropping system”.

This was not completely accurate: in his survey of British breweries, Barnard described the dropping system being used by brewers from Bristol to Newark, and down via London to Kent. It was certainly popular in the capital’s breweries. Derek Prentice, formerly a brewer with the London brewers Truman Hanbury and Buxton of Brick Lane and then Young & Co of Wandsworth, and now with Fuller Smith & Turner in Chiswick, used the “dropping” method to produce beer at both Truman’s and Young’s, and told me that the sites where the “settling squares”, the bottom part of the dropping system, used to be can still be seen at Fuller’s.

Another London brewer, Whitbread, also used the “dropping” method until at least the 1950s. A publication called A Book About Beer, brought out by Whitbread in 1955, described the brewing process so:

When the yeast has reached its maximum activity, the whole mixture is ‘dropped’ to a second vessel – a slate tank – on a lower floor. In this second stage the major yeast reproduction takes place and the process of conversion of wort into beer is completed. Finally the yeast is ‘skimmed’ off, that is to say, withdrawn by suction through the broad funnel which runs across the vessel. Fermentation normally takes about three days but it is usual to allow the beer to cool and settle for a further similar period.

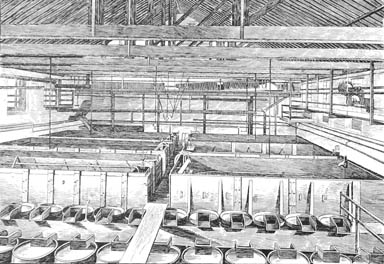

A drawing made at the time of Alfred Barnard’s visit to Whitbread’s brewery in 1889 showed that at that time it was using another, slightly different version of the dropping method as well, the “ponto” system. This involved dropping the beer down after its first fermentation into round vessels called pontos, which were fitted with a lid and a protruding wooden lip across which the excess yeast flowed into a trough. Barnard indicates that pontos were used in particular by the big porter brewers: on a trip to Thompson’s brewery in Walmer, Kent in 1890 he wrote:

The cleansing room next claimed our attention, a room 80 feet in length, containing two settling backs and 400 ponto vessels, commanded by five capacious topping tanks. It is in these utensils that the wort is cleansed. These ponto vessels are familiar enough in the London porter breweries, but we had not seen them before in the country.”

Other country brewers certainly did use pontos: in 1860, for example, EK & O Fordham in Ashwell, Hertford- shire, erected a new brewery and sold off old, unwanted kit which included five working squares and three eight-barrel pontos. (Curious word, ponto – it doesn’t appear to be in the Oxford English Dictionary, and its derivation is unclear. My guess – and it’s just a guess – is that it comes from the resemblance of the wooden lip sticking out from the top of the vessel to the end of a pontoon or punt – see picture of Whitbread’s Great Tun Room.) As Barnard indicates, the pontos were fed by topping tanks, to keep them full as the yeast flowed out into the troughs. Pontos must have been swines to keep clean, and it looks as if, even in Barnard’s time, they were going out of use. The Encyclopedia Britannica of 1911 treated the ponto and “ordinary” dropping systems as variants, and said:

The principle of the Dropping System is that the beer undergoes only the main fermentation in the “round” or “square,” and is then dropped down into a second vessel or vessels, in which fermentation and cleansing are completed. The ponto system of dropping, which is now somewhat old-fashioned [my emphasis], consists in discharging the beer into a series of vat-like vessels, fitted with a peculiarly shaped overflow lip. The yeast works its way out of the vessel over the lip, and then flows into a gutter and is collected. The pontos are kept filled with beer by means of a vessel placed at a higher level. In the ordinary dropping system the partly fermented beer is let down from the “squares” and “rounds” into large vessels, termed dropping or skimming “backs.” These are fitted with attemperators, and parachutes for the removal of yeast, in much the same way as in the skimming system. As a rule the parachute covers the whole width of the back.

The Encyclopedia Britannica added that “The Burton Union System is really an improved ponto system”, which means that the ponto idea lives on, at Marston’s brewery in Burton upon Trent, the last big brewer to use the Burton Union system of fermentation..

Barnard had quite a lot to say about the dropping system during his visits to more than 100 breweries around the British Isles between 1889 and 1891. This is his description of the fermenting hall at WJ Rogers’s Jacob Street brewery, Bristol, for example:

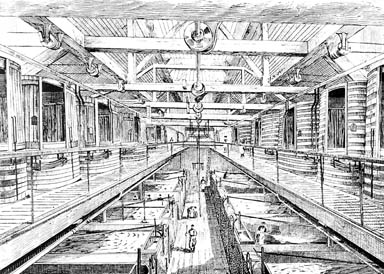

On either side of this extensive room, which is upwards of 50 feet high, are long galleries supported by iron columns containing a most impressive collection of fermenting vessels. They are 18 feet wide, and contain … ten fermenting rounds of large capacity, constructed of English oak … Placed on the floor of the tun room, beneath the galleries, there are to be seen a similar number of cleansing squares, each measuring 20 feet by 12 feet, which are used for receiving the partially fermented liquor from the “rounds” above. They are all fitted with powerful attemperators and copper parachutes, also a skimming apparatus for taking the yeasty head off the beer simultaneously and driving it into the parachutes.”

He went into more detail on the dropping system for his visit to another local brewer, Charles Garton of Lawrence Hill, Bristol, who used a similar set-up to Rogers, but with a separate “lower fermenting room or cleansing room” on the floor below the “Great Tun Room”, Barnard said that

The process of ‘cleansing’, or separation of the yeast from the finished beer, is an important and delicate one, requiring the constant use of the thermometer, as the brewer takes great care that cleansing shall not commence too soon for strength and quality of the goods. The cleansing is allowed to take place at the meridian stage of the fermenting fluid, and the brewer’s object is then to reduce the heat and allay the fermentation. This being accomplished, the lighter yeast, which rises to the surface, is skimmed off, the heavier yeast descends to the bottom and fermentation gradually declines as the cleansing draws to a conclusion.”

Confusingly, the dropping system was also known as the skimming system, since in the lower fermenting vessels the excess yeast would often be skimmed off by drawing a plank across the surface of the vessel, pushing the yeast into the mouth of a “parachute” or funnel suspended in the vessel, from which it flowed down a pipe through the floor to another tank below. However, skimming into parachutes was (and is) also used in breweries that carry out all the fermentation in a single vessel, without dropping. Barnard was not always careful with his terminology: when he visited Stansfeld & Co’s Swan brewery in Fulham, West London, he wrote that the fermenting room had

“along the centre of the floor … an opening railed all round, for supplying light and ventilation below. Placed around this opening are thirteen fermenting vessels, huge square structures of English oak … each of 120 barrels content … In the room below, to which we next descended, are the skimming vessels, constructed of slate, also fitted with attemperators and each containing a copper parachute … the apparatus for working the parachutes is actuated by a worm and wheel easily adjusted to the surface of the beer so that the yeast can be carried off without disturbing the beer … From the foregoing observations the reader will understand that this brewery was designed expressly [by William Bradford in 1881-82, the same man who designed Sich’s Lamb Brewery, next door to Fuller’s in Chiswick – Z] to carry out what is known as the skimming system, which differs from all others, in so far that the fermentation is not carried out entirely in one vessel, but is begun in the fermenting squares and completed in the skimming backs. It is contended that it tends to produce a cleaner and brighter article than any other while, as compared with the Burton system, it does not entail the multiplicity of small vessels, with the almost insuperable difficulty of keeping them thoroughly clean, which characterises the latter.”

Clearly what he is describing is the dropping system, even if skimming took place at the end. In 1890 Barnard visited Warwick & Sons’ brewery, Newark, Nottinghamshire, where on his tour he saw

the new, or No 3 fermenting room, which, when completed, will be the finest in the brewery. It will contain twelve fermenting squares and twelve dropping vessels, A few of the vessels had just been placed at the time of our visit, and our guide informed us that the system of fermentation carried on would be a mixture of the skimming and drop systems.”

For brewers, the dropping system has a number of advantages, Derek Prentice says:

First, purifying or “cleansing” of the partially fermented beer, by leaving behind protein deposits (cold break) that had sedimented to the bottom and those that had collected in the first rocky head (first Krausen). These can potentially cause “off” flavours in the final beer. This has a parallel in some traditional German breweries with a process known as flotation where the chilled wort has air bubbled through it and the resulting floating deposits are removed.

Second, aeration of the wort, causing a surge in yeast growth; this was particularly important in the days of open coolers where wort aeration was very rudimentary and would have required boosting at this stage to ensure a good fermentation.

Brakspear additionally likes to claim that the dropping system used to make its beers helps them “develop the special delicate butterscotch flavours for which Brakspear Bitter is acclaimed.” This occurs when yeast secrete alpha-acetolactate into the wort, which is oxidised to diacetyl: normally the yeast takes back the diacetyl and the toffee/butterscotch flavours disappear, and it must be said that many brewers regard their existence in a finished beer as a fault (they’re certainly a fault in excess, as anyone who has been served a too-young pint of cask ale full of diacetyl will agree.)

Derek Prentice says of the system as he knew it that

The vessels that received the dropping beers were variously known as cleanse batches (Truman’s) settling squares (Fullers) cleanse vessels (Young’s). They were typically fairly shallow and often fitted with skimming systems for yeast removal. These skimming systems included parachutes, weirs and, more latterly, vacuum adaptors. The yeast collection vessels were normally situated immediately below the cleansing vessels, allowing gravity to perform the task of yeast cropping. The large surface area of the vessel meant that a good yeast crop could be harvested without the danger of a deeper, heavier head collapsing back into the beer.

“The shallower vessels also meant that the fermentation was not as vigorous as might be expected in deeper vessels and the fermentation naturally arrested at a slighter lower attenuation. The yeast left in solution in the beer post-skimming, because of the shorter distance, settled to the bottom of the vessel quicker than in deeper vessels (hence the names cleansing or settling). This combination of lower yeast counts and the degree of residual fermentability in the beer made this system ideal for the production of cask-conditioned beers as no further processing was required prior to putting into cask.”

One of the last breweries besides Brakspear to still use the dropping system was a local rival, Morrell’s of Oxford, which, sadly, closed in 1998. Morrell’s had a unique (as far as I’m aware) wrinkle on the system: dropping into conical fermenters. To quote from its company history, written in 1994:

… The brewery achieved a break-through in 1969 when it acquired two eighty-barrel Nathan fermenters, rather like large laboratory test-tubes with cooling panels welded on the outside, which Whitbread had used before building their new Luton brewery. … Morrells had always used the ‘dropping’ system, which is a way of cleansing the fermenting wort of sedimentary matter which forms in the early phase of fermentation. Cooled wort pitch with yeast was collected in an open square and sixteen hours later dropped into a fermenter leaving the sediment behind. The ‘dropping’ system was continued with the Nathans and by good fortune a yeast was acquired which would settle at the bottom of a Nathan but would come to the top of a relatively shallow open skimming vessel. The new system of collecting yeast from the bottom of a conical vessel was greatly favoured. It was simple, most hygienic and labour saving. Yeast could be collected for immediate pitching into a subsequent brew or collected and stored in the refrigerator.

So successful was this method that, in January 1971, the four fermenting vessels that had been in use since 1896 were scrapped and the fermenting room gutted, before a new top storey was added to this early 19th century part of the building at right angles to the tun room. Meanwhile, in March 1971, three further conical fermenters, each weighing 3 tons and capable of holding 140 barrels of wort, were acquired for the brewery and lowered one weekend by mobile crane through the fermenting room roof. Three further conical fermenting vessels have since joined them and remain in constant use as part of Louis [Gunter, head brewer]’s legacy to the brewery.”

My grateful thanks to Derek for his invaluable help in producing this post. Today a couple of new small brewers, one in the Midlands, one in the United States, are believed to have revived the dropping system. If anybody knows of any brewery other than Brakspear’s still using the system, I’d be very interested to hear about it.

Excellent as usual, however, one question:

The word yeast, is used throughout this article.

Is this yeast as we know it today, the single celled organism, or is the word yeast used for the foam on the top? Granted by gathering the foam they were getting the yeast, but the word yeast (yeste) had been used since before 1680.

It was 1680 when van Leeuwenhoek saw it under a microscope, however it wasn’t until 1857 when Pasteur said it was used for alcohol.

Much of your article is from the last 1800’s, so I’m just wondering if it’s actual yeast, or Krausen that was referred to in the older documents.

Marstons produce a bottled beer called Double Drop which they say is produced by the double drop system.

Marston’s Double Drop

Crafted using the almost forgotten “double dropping” fermentation technique to deliver a fresher and brighter beer that brings out the full (malty flavour of Maris Otter “the king of brewing barley”) clean flavour of the malt. A large application of late hops are added to the wort kettle to enhance the aroma and give a sense of the bitter flavour of beers of the past.

You’re right, I had forgotten myself about that … any more?

Brian Glover in ‘Cardiff Pubs and Breweries’ tells how Hancock’s quietly abandoned their double drop system in the 1950’s. He says,

“It was ideal for the lower-gravity light milds for which Hancock’s were famous. It was the system which created Hancock’s character.”

Brian says Hancock’s were unusual in Cardiff for using the system and that getting rid of it doubled its fermentation capacity from 2,000 to 4,000 barrels a week.

Easy to see why the system disappeared although it was to the detriment of the drinker. I spent many hours musing on how Brakspear’s could make such a beautiful pint as their Ordinary bitter at such a low gravity.

Excellent article.

Speaking from a homebrewing point of view, I’ve found that dropping into another vessel during the vigorous stage of fermentation makes a significant difference to beer quality: better attenuation thanks to the extra aeration/rousing of the yeast; less sediment so the beer clears more easily when it’s racked; and it’s less likely to develop off-flavours from autolysis of dead yeast. The downsides are that it means extra work, requires an extra vessel, and introduces an extra opportunity for infection. But I suspect that dropping is far more common among homebrewers than commercial breweries these days.

Tom,

Do many homebrewers still drop? Most people I know that have tried it report stuck fermenations. I suspect they drop to early or late in the game. I have never tried it. Graham Wheeler is still an advocate for dropping.

For homebrewers that have tried this – is there a noticeable difference in doing this as opposed to doing a secondary after the main fermentation has finished? We’ve reintroduced the secondary after we stopped for a while – our laziness was “rewarded” with lots of brews that tasted like marmite. Getting rid of the yeasty trub before bottling definitely makes a difference.

I love Brakspear’s beers, and if I could produce anything half as good I’d be a truly happy woman.

I love Brakspear Triple. I stocked up in Asda, 2 weeks ago, for 1.5£ each.

Just opened a new (quite expensive) book and found this:

“The point at which we start to cleanse the beer, that is to free it from suspended impurities either by skimming them off, or else by allowing them to be naturally thrown out from unions, pontoes, or the old-fashioned working casks, depends not only on the kind or quality of beer we are dealing with, but also upon the kind of fermentation we are conducting.”

“The Art of Brewing” by F. Faulkner, London, 1876, page 106.

Great topic, cleansing. The Victorians were obsessed with it. Has it died out?

Matt: I should have stated up front that I’m not a particularly serious homebrewer myself and certainly no authority on what other homebrewers get up to. Other than personal experience and a few brewers I know, what makes me suspect that it’s more common among homebrewers (UK ones, anyway) is that I learnt about it from one of Graham Wheeler’s CAMRA brewing books. While far from perfect in other areas, Wheeler’s practical info was streets ahead of any other references available to me when I first read him in the early 90s and, if homebrewing forums are anything to go by, it’s still much used. I think you’re right about stuck fermentations – you definitely need to drop early (1 or 2 days after pitching, while fermentation is vigorous).

Boak: FWIW, after primary fermentation I also move the beer into a pressure barrel to mature before bottling, so I’m not suggesting dropping as an alternative to secondary fermentation. I think it can have a beneficial effect, especially if you’ve had problems with nasty yeast flavours, but Ron’s quote implies that maybe it’s not so good for certain beers or yeast types. More research needed 🙂

Virgil G – references throughout to yeast mean the organism we know today. British ale brewers traditionally cropped their yeast for reusing in subsequent brews from the “foam” on the top of the completed brew, thus, semi-deliberately, maintaining the “top-fermenting” nature of their yeasts.

Ike – thanks for the Brian Glover reference, that’s one of his books I haven’t got, clearly I’m going to have to buy it now …

Ron – thanks for that quote – “working casks” is, I’d guess, a reference to the habit of dropping the beer after the initial fermentation into the “carriage casks”, the ones that went out into the trade, to finish fermenting, which may have been “old fashioned” in the 1870s, but Bateman’s was still using this method in the early 1950s (and I bet they weren’t the only small British brewer doing likewise …)

As a homebrewer diacetyl and oxidation would be my main concerns with dropping.

What do Marston’s do to make it a double drop rather than just a drop?

I think they’re saying “double drop” because they regard the first “drop” as being into the initial fermenting vessel and the second “drop” being from that vessel to the final fermenting vessel …

Hi

Having googled “Double Drop system” I have just found my way to your article of Sept 2008 “A tasty drop: the history of an almost-vanished fermentation system”.

On the Brakspear webpage for their Double Drop it says “After 16 hours the beer is then allowed to fall naturally or ‘dropped’ into the vessel below. In this process any protein or solid material is left behind in the top-fermenting vessel.”

I have recently been diagnosed with coeliac disease, which means I have to keep my gluten (a protein) intake down. I am currently struggling on a beer-free regime and I now wonder if this is necessary. Do you know whether any gluten would be left in such a beer, and if so how much? From their webpage it would seem not but this seems too good to be true.

Regards

David Bennett

David, I am very far from an expert and you’d really need to speak to Wychwood/Marston’s (who own Brakspear), but my feeling is, alas not: this is big, lumpy bits of protein they’re getting rid of, “gick”, and I believe there’s still going to be gluten left in the beer. But ask Marston’s: they’d know very much more than I do on the subject.

Apologies for coming to the party so late, but I’m carrying a sharing-bottle of something very nice :~)

@Partizansmith on Twitter led me to this topic yesterday, then today, I picked up a recent-ish issue of CAMRA’s ‘Beer’ magazine. It included a nice piece by Roy Bailey about the past, present & future of the beautiful Donnington Brewery, it mentioned that they use the dropping system, after 24hrs in the first FV.

At Brakspear’s Henley, as a Tun Room brewer, one of my jobs was to ‘drop’ the previous day’s beers from the round open dropping vessels to the squares below – nothing to it really, apart from watching to see that it wasn’t flowing too vigorously & foaming out the top of the FV.

Thank you for sharing that, Mike: interesting indeed. Clearly another example of “it ain’t broke”.

David,

I hope you read this. I don’t know if it is available where you live, but here in the USA we have beer made from sorghum. It is 100% gluten free. I can’t comment on the flavor because I’ve never tried it, but I just thought it would be a good option for you.

Colchester brewery do a nice double drop beer Brazilian a special porter