The “we ran a pub” category of published biographical reminiscence is small, but still includes several classics: John Fothergill’s An Innkeeper’s Diary, for example, arch and snobby, with dropped names covering every page like drifts of autumn leaves – “Ernest Thesiger turned up for the first time … the D’Oyley Cartes came with their usual big party” – and George Izzard’s One for the Road, about the Dove at Hammersmith, which is less snobbish but almost equally rammed with famous customers (“Alec Guinness came in and ordered the drink most appropriate to his name … Dylan Thomas never drank heavily at the Dove. His usual order was a pint of mild and bitter.”)

The “we ran a pub” category of published biographical reminiscence is small, but still includes several classics: John Fothergill’s An Innkeeper’s Diary, for example, arch and snobby, with dropped names covering every page like drifts of autumn leaves – “Ernest Thesiger turned up for the first time … the D’Oyley Cartes came with their usual big party” – and George Izzard’s One for the Road, about the Dove at Hammersmith, which is less snobbish but almost equally rammed with famous customers (“Alec Guinness came in and ordered the drink most appropriate to his name … Dylan Thomas never drank heavily at the Dove. His usual order was a pint of mild and bitter.”)

Now another behind-the-bar tell-all has arrived, doubly unique because it’s about a female mine host, rather than the usual landlord’s tale, and it has been written by the grand-daughter of the main character, not the person whose name was on the licence. But The Last Landlady, by Laura Thompson, deserves your attention for more than its celebration of women running pubs: it is both a paean to a particular successful and charismatic female publican, and an elegy that, ultimately, commemorates and mourns what Thompson clearly feels is a fading, vanishing, dying version of pub life, where landlord/landlady and customers were willing actors in a daily drama, each knowing their parts and performing them for the satisfaction of themselves, their audience and the others in the cast. Thompson’s grandmother Violet Ellis was, it is clear, one of the great bar owners, barely known outside her small section of rural England, but queen of all that lay under the shadow of her innsign and at the same time – if I may mix myself a metaphor – ringmaster of the circus that performed twice daily between 11am and 2pm, and 6pm and 10.30.

But the book is called “The Last Landlady” because, Thompson clearly believes, the sort of landlady Violet was, the sort of pub that Violet ran, no longer exist, can no longer exist, when fewer people visit their local regularly – fewer people even have a local – and the opportunities for women like Violet to be the stars in their own long-running show, an attraction in the daily theatre of the pub deserving of higher billing even than the drink and the craic, have vanished in an era where the idea of the pub as a club that anybody can be a member of, that having the price of a pint in your pocket empowers you to lift the latch of the public or saloon bar door and enter a separate world where everyone is, or should be, on their best and brightest behaviour, has itself vanished, and the pub is simply a place to get cheap food and watch top sporting action on a screen probably only a little larger than the one in your own living room.

Thompson does not name the pub that her grandmother ran, saying only that it was “in the rural Home Counties”, but there are enough clues in the book to identify it as the Cross Keys, in the village of Totternhoe, close by Dunstable Downs, and some six miles to the west of Luton. She does not name the pub that her grandmother’s father, John (or Jack) Solomon, had run, either, called in the book “the old pub”, which her grandmother had expected to take over when her father died. But again there are enough clues given to identify it as the Richard III in Castle Street, Luton.

John Solomon has a terrific back-story: he was born in Sidney, Australia, and – or rather, because – his great-grandfather was Isaac “Ikey” Solomon, one of the most notorious criminals and fences in early 19th century England, and the man that Charles Dickens based the character of Fagin on. Ikey Solomon had escaped from custody in London in 1827 and fled to America, but his wife Ann had been found guilty of receiving stolen goods and sentenced to transportation to Tasmania, where she arrived together with several of their children. Ikey learnt of this and travelled to Tasmania himself to be with his family but was eventually arrested by the colonial authorities and shipped back to England for trial. The punishment the court in London imposed, somewhat ironically, was transportation back to Tasmania. Ikey Solomon’s third son, David, who was only nine when his mother was sent to Van Diemen’s Land, settled in Tasmania, and married. One of his sons, Alfred, moved to Melbourne, and then Sydney, before emigrating back to London around 1877, living in Paddington with his family, including the young John, who was aged two. None of that is in The Last Landlady – probably because it doesn’t really fit the narrative, rather than because it’s embarrassing to say “I’m descended from the man who inspired Fagin.” But I’m a journalist, and I love a story that will make readers go “Wow!”, whether it integrates smoothly into the plot or not.

John Solomon is supposed, according to one source, to have “played for Queens Park Rangers in the first year they turned pro,” which would have been 1889, when he was only 14 – no record can be found to substantiate this, though he was living in the right part of London, Paddington, to be a QPR supporter – and to have “spent a number of years as head foreman to a London brewery.” He does, at least, appear to have worked at a brewery, since his occupation is described in the 1901 and 1911 censuses as “beer cellarman” and the industry he worked in as “beer bottling”. He was still living in Paddington in 1914, when Violet was born, the first girl after five boys to John and his wife Alice, who came from Bristol. In October 1916, however, John had the licence of the Richard III in Luton transferred into his name, the existing licensee, Ambrose Holland, telling licensing magistrates that he was now a soldier and his wife was unable to carry on the pub.

The Richard III (still open today, under the name O’Sheas) was originally a row of cottages, converted to a public house in 1846, and was rebuilt by its brewery owner, JW Green’s of Luton, in the 1930s in a very neo-Georgian style, with a red brick frontage extending up above the bottom edge of the roof. By 1939, aged 25, Violet was a manageress there, along with her husband, Charles Ellis, and their five-year-old daughter Josephine, while John Solomon, then 64, was the licence holder. Alice Solomon died in 1943, and with her husband apparently called up into the armed forces and her father now in his late 60s, Violet was effectively, as Thompson calls her, the châtelaine of the Richard III, running the pub on her own. Ellis seems to have disappeared out of the door (he and Violet were divorced in 1944 – Thompson says the divorce took place “just after the war”, but reveals that it was granted on the same day that the actress Jessie Matthews was divorced, which allows it to be dated to the month after D-Day). When her father died in 1952, aged 77, Violet must have had the expectation that the brewery would allow the licence of the Richard III to be transferred into her name. She had, after all, lived at the pub for all but two of her 38 years, and been involved in running it for a fair slice of that time, much of it with only an elderly father to help.

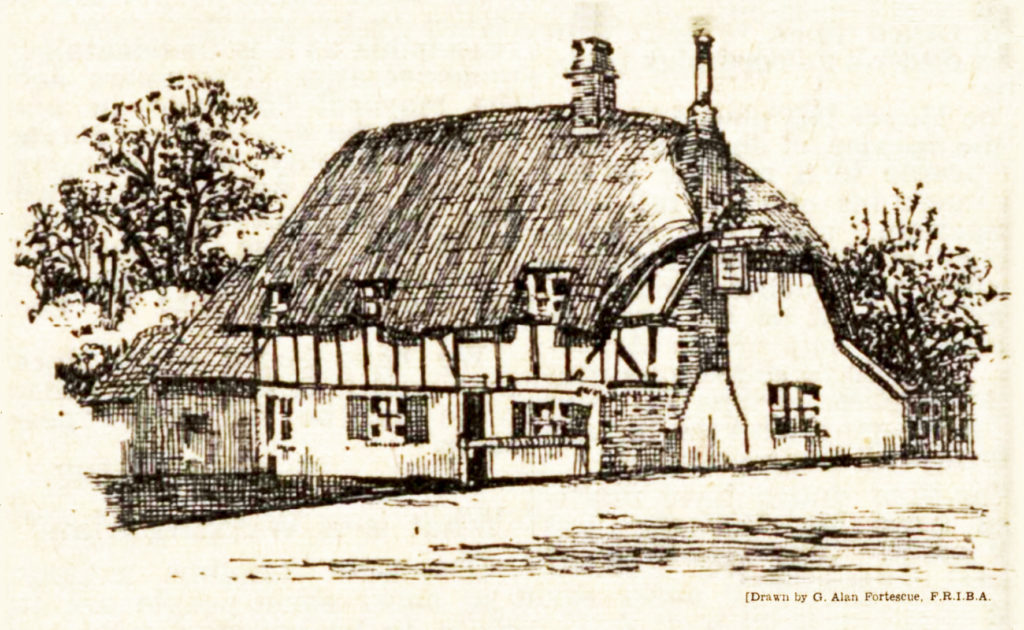

However, the brewery would not let her have the licence: according to Thompson, it was because she was a daughter, and not a wife – or a son. It was a knock-back, but strings, apparently, were pulled for Violet by influential friends, and Whitbread’s brewery in London eventually offered her the licence of the Cross Keys, which it had acquired from the owner four years earlier. The pub had literally just been designated a Grade II listed building, on the grounds that it dated from at least the 16th century (claims have been made that it is even older, first appearing in the 1420s), but it was run-down, with no proper bar, no bathroom, no real upstairs floor – the pub sitting room stretched up to the height of the thatched roof – an outside privy and a customer base of ruddy-faced local farmers and dominoes enthusiasts. Whitbread sent the builders in, the sitting room was given a real ceiling, with a bathroom installed above, a bar was built, the “cellar” (actually an outside shed) revamped and thatched to matych the main building, and Violet, “black-haired, bejewelled, bohemian”, installed herself behind the bar, where she would graciously accept whiskies from admirers, surreptitiously tipping them out onto the floor by her stool.

According to Thompson, Violet was “the first woman in England to be given a publican’s licence in her own right, that is to say, as neither a wife nor a widow.” As it happens, the history of the Cross Keys itself destroys this claim. The name of the pub, incidentally, is both easy and difficult to explain. Totternhoe was home for hundreds of years to quarries that dug out the soft local clunch, or chalk, easily worked, which make great building stone for the interiors of churches. Henry I founded the Priory of St Peter, Dunstable, in or just before 1124, and endowed it with, among other riches, the quarry at Totternhoe. The badge of St Peter is, of course, crossed keys. The pub’s sign thus strongly suggests a link with the Augustinian foundation of St Peter in Dunstable, through the priory’s ownership of the nearby quarry. But the priory was dissolved by another King Henry in 1540, and whatever the age of the building it occupies, the pub is first named as such only in 1808, in an advertisement in the Northampton Mercury. Is it credible that folk memory kept the link between Totternhoe and St Peter’s Priory alive for more than 250 years, to give the Cross Keys its name? Anyway, returning to the main tale: by 1824 the landlord was John Clements, who was born around 1799. He ran the Cross Keys for more than 40 years, but by 1871 he was dead, and his eldest daughter Mary, then aged around 37, was listed as the licensee at the Cross Keys. Mary, known as “Miss Clements”, was still in charge in 1890, but by 1902 her younger sister Hannah, then 61, was the licensee. Hannah died “in harness” at the Cross Keys in February 1909, aged 68. So the Cross Keys had female licensees who weren’t wives or widows, but daughters. for a stretch of at least 37 years, almost half a century before Violet.

This is not the only story in the book to make the fact checkers twitch. Thompson says Violet would speak of another pub a few streets away from her father’s:

“The daughter of this pub’s landlord was a few years older than my grandmother, equally attractive although in pure English style. In youth she too served behind the bar, and received the adoration owing to the dauphine; this, however, was not enough for her. She went to London, became a C.B. Cochran chorus girl, married one of the biggest film stars of the day and ended up the wife of an earl.”

This would be Sylvia Hawkes, and the real story is even more spectacular than Thompson’s version. Sylvia was step-daughter (rather than daughter) of the landlord of the Painter’s Arms in High Town Road, Luton from at least 1925, Frank Swainson, and one of the most successful serial brides of the 20th century, married to not one but two of the biggest film stars of the day, as well as a baron, a prince, and, not actually an earl, but the eldest son of an earl.

Sylvia was born, like Violet, in Paddington, in 1904, and worked as a lingerie model in the early 20s, before becoming a dancer in the productions put on by the theatre impresario CB Cochran, starting with the Midnight Follies, and swiftly, beginning in 1924, moving into acting. Despite claims, it is not clear if she ever did appear behind the bar at the Painter’s Arms: one source reckons she “ran away from home at the age of 15”. In 1927 Sylvia made her first marriage, to Anthony Ashley-Cooper, Lord Ashley, eldest son and heir to the Earl of Shaftesbury: it was one of the year’s great scandals, as the Earl and Countess fought to dissuade their son from marrying the actress, threatening to disinherit him and cut off his allowance. The day before the wedding, the Earl was denying that it would take place, while Lord Ashley’s sister was declaring: “Such an alliance is unthinkable. An Ashley-Cooper can never marry a Follies girl.” When a telegram arrived at the Shaftesbury’s 17th century ancestral pile in Wimborne St Giles, Dorset announcing that the wedding would be happening that morning, the earl and countess threw themselves into a limousine and ordered their chauffeur to break all speed limits to get to the church in Knightsbridge, 120 miles away, to try to stop the ceremony. They arrived only in time to see the newly weds leaving the church, to the cheers of a huge crowd, with women, it was reported, fighting to see the bride.

It was also reported that Lord Ashley had been in such haste to organise the marriage that he had not bought a wedding ring large enough to fit his bride, and “was obliged to hold it at the end of her hand, looking rather foolish. This detail does not affect the legality of the ceremony, but superstitious people say it brings bad luck.” So it proved. Less than 18 months after the wedding, Sylvia and Lord Ashley had parted, the actress apparently unhappy with life on a farm in Worcestershire. She moved to Hollywood, as “Lady Sylvia Ashley”, though if she ever made any films there they appear to be desperately obscure. However, she became a big hit with Douglas Fairbanks Snr, one of Hollywood’s superstars, starting an affair with him that led to his separation from his fellow Hollywood star Mary Pickford, in 1933, and Sylvia’s divorce from Lord Ashley the following year. Sylvia and Fairbanks married in 1936, but he died of a heart attack only three years later. The widow Fairbanks then returned to England, where in 1944 she became the second wife of Edward John Stanley, 6th Baron Sheffield, 6th Baron Stanley of Alderley and 5th Baron Eddisbury. That marriage lasted just four years, and Sylvia was back in Hollywood, where in 1949 she married her second movie superstar, Clark Gable: it has been said that she reminded him of his previous wife, Carole Lombard, who had died in a plane crash in 1942. Within three years Sylvia and Gable had also divorced: undaunted, in 1954, Sylvia picked up her fifth wedding ring, marrying Prince Dimitri Djorjadze, a Georgian nobleman, racing car driver, racehorse owner and hotel executive. This time the now Princess Sylvia Djorjadze stayed married until her death in 1977, though she was apparently separated from her new husband within less than a year. She died in Hollywood, and is buried in the Hollywood Forever cemetery. It was a tremendous career for a former Luton publican’s stepdaughter.

There are also a few missing facts in The Last Landlady more pertinent to Violet’s story: no mention of the fire at the pub in April 1966, which destroyed the thatched roof and upper storey, nor her second husband, Roy Barrett, who was running the pub with Violet at the time: the pair lived in a caravan in the grounds until the Cross Keys was repaired. Again, like Ikey Solomon, Barrett and the fire are most likely omitted because they would interfere with the flow of the narrative. Never, as journalists like to declare, let the facts get in the way of a good tale.

Because this is a good tale, a great tale, filled with terrific, well-presented anecdotal evidence of how one woman, through her will, her charm and her innate talent as a landlady, turned a run-down rural inn into a PUB in capital letters, a place with personality in every brick and beam – and how the kind of pub Violet ran is evaporating away, doomed, Thompson fears, to disappear:

“The process whereby pubs ceased to be the cornerstone of people’s lives was slow … They were still loved. They still are loved. But gradually they ceased to be intrinsic to society …Without the ballast of unquestioned love, the knowledge that it was wanted, the pub faltered.”

Decline, Thompson says,

“did not begin in the 1980s, yet there was something about that time that was inimical to pubs … It was the aspirational quality that was unleashed by money-centricity, all that Sloane Ranger Handbook and property porn and Filofax-flaunting, which in different form is still with us … Put very simply, the pubs that moved with the times, that acquired wine lists and logos and a matte veneer, became a part of that brighter new world. The pubs that were left behind, that retained their connection to the bench and the sawdust, that for all their roughness remained innocent – they were implicitly the habitat of the unevolved, the victims, those who had failed to aspire … The notion of a pub as a place where people simply congregated, a social hub that did not need to be named as such because nobody would have doubted it, or even thought about it, all this was evaporating.”

This is a thesis that rejects the smoking ban and greedy pubcos as the major causes of the scything down of pubs over the past 30 years, and points instead to deeper changes in society, in people’s needs. It suggests that the pub, as we knew it, is no longer wanted, and ultimately doomed. I wish I could deny this with total confidence.

Delighted you’ve flagged this up as I’m currently reading this – as you say a great tale.

[…] – If Marytn Cornell says to read a behind-the-bar tell-all book you probably should. […]

[…] – If Marytn Cornell says to read a behind-the-bar tell-all book you probably should. […]

Martyn,

The book was well reviewed in the TLS Christmas Issue (Dec 21 & 28, no. 6038/9) by Catharine Morris, but she failed to identify the pub’s location. A chance for a letter to the editor? “Sir,…”

Mike