A fascinating pair of pieces of ephemera, these, because they tells us something about brewing and beer consumption in large households and by farmers, and give a clue as to why farmers who brewed sometimes became actual commercial brewers.

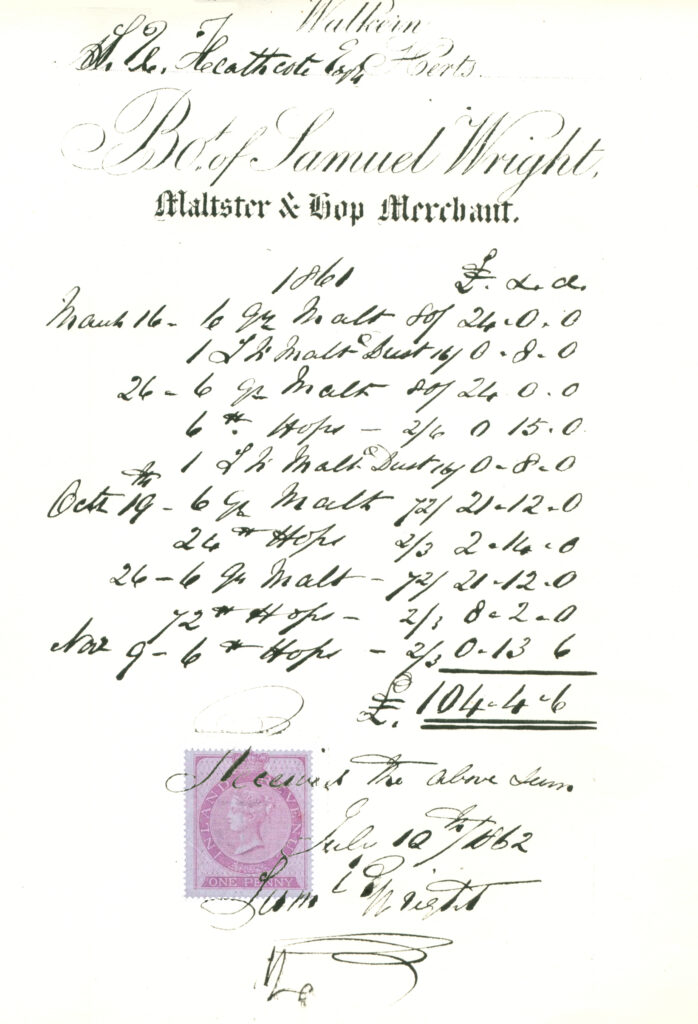

The first is a 163-year-old bill for malt and hops from Samuel Wright of Walkern in Hertfordshire to “S. U. Heathcote”. That is Samuel Unwin Heathcote, Lord of the Manor of Shephall, and owner of Shephalbury Manor, three miles south of Walkern. Samuel Wright was already a brewer, as well as a maltster: in February 1855 he was advertising in the Luton Times and Advertiser: “Pure ales and stout brewed with water from our own artesian well. Also aerated waters of the finest quality … Samuel Wright & Co, Brewers and Maltsters, Victoria Brewery and Mineral Water Works.” However, he was happy to supply malt, and hops (and malt dust), to private brewers such as Heathcote.

The six quarters of malt at a time that Heathcote bought in 1861 would have been enough to make perhaps 24 barrels of beer, which would have been supplied to the servants and farm workers at Shephalbury Manor, as well as the family (I’m ignoring the malt dust Heathcote was buying because I have no idea what difference that might have made to yields …) Over the year that works out at 96 barrels, or just under 76 pints a day. If that sound a great quantity of beer, the average number of male farm workers per farm in Hertfordshire in 1851 was 13. Let’s guess that Heathcote was, as a substantial landowner, employing twice the average, that gives him 26 workers. That’s three pints per day per man, which sounds perfectly reasonable for the time.

Let’s pause for a discussion of Samuel Heathcote, one of the wackier characters of Hertfordshire history, described by his contemporary, the Quaker brewer William Lucas of Hitchin, as “insanely violent”. Samuel Heathcote Unwin Heathcote (1789-1862) was born Samuel Heathcote Unwin, eldest son of Samuel Unwin of Sutton-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire, a wealthy cotton goods manufacturer, and Elizabeth Ann Heathcote.

His maternal grandfather, Michael Heathcote, a London merchant, had bought a one-third share in Shephalbury Manor from one of the daughters of the last male member of the Nodes family, lords of the manor of Shephall since 1542, and was living at Shephalbury. Samuel Heathcote Unwin inherited this share of the Shephalbury estate from Michael, one of the stipulations in his grandfather’s will being that to gain his inheritance, Samuel had to add Heathcote to his surname. Samuel was apparently bought up at Shephalbury by his grandfather after his father died and his mother remarried. Michae Heathcote died about 1812, and Samuel was in charge at Shephalbury by 1817 when, as a substantial landowner in the district, and Lord of the Manor of Shephall, he was one of the nominations to be Sheriff of Hertfordshire. (Samuel acquired the other two thirds of the estate in 1838, but had presumably been leasing them before then.)

He was also a “stern unbending Tory”, who fought every advance in mid-19th century society: he opposed Catholic emancipation, parliamentary reform, the abolition of the corn laws, the setting up of a county police force, the introduction of the Poor Laws and the arrival of the railways. In October 1846, when the Great Northern Railway surveyors were marking out the line of the railway to York at Little Wymondley, just north of Stevenage, on land owned by Heathcote, the squire of Shephall marched up “at the head of a body of the peasantry” and began to pull up the stakes that had been put down to mark out the line of the railway. Heathcote himself picked up one of the surveyors’ theodolites “and threw that instrument a distance of thirty feet, whereby it had been so much damaged that it was now useless.” He appeared in court charged with obstructing the engineers and surveyors of the GNR, but the charges were dropped after he promised not to interfere with their work again.

Samuel died on March 2 1862. The Hertford Mercury and Reformer, which, as its name indicated, was opposed politically to everything Heathcote attempted to defend, and had been mocking him since it was founded in 1834, still said of him that “if wrong-headed he was always right-hearted … his tenantry found him a just and generous landlord; the poor by whom he was surrounded a kind and considerate helper; and those of his own rank, with whom he associated, a faithful, intelligent and genial friend.” One gets the impression that if you turned up at the door of Shephalbury manor, whether tramp or gentleman in a carriage, you would not have to wait long to be offered a glass of fine home-brewed ale.

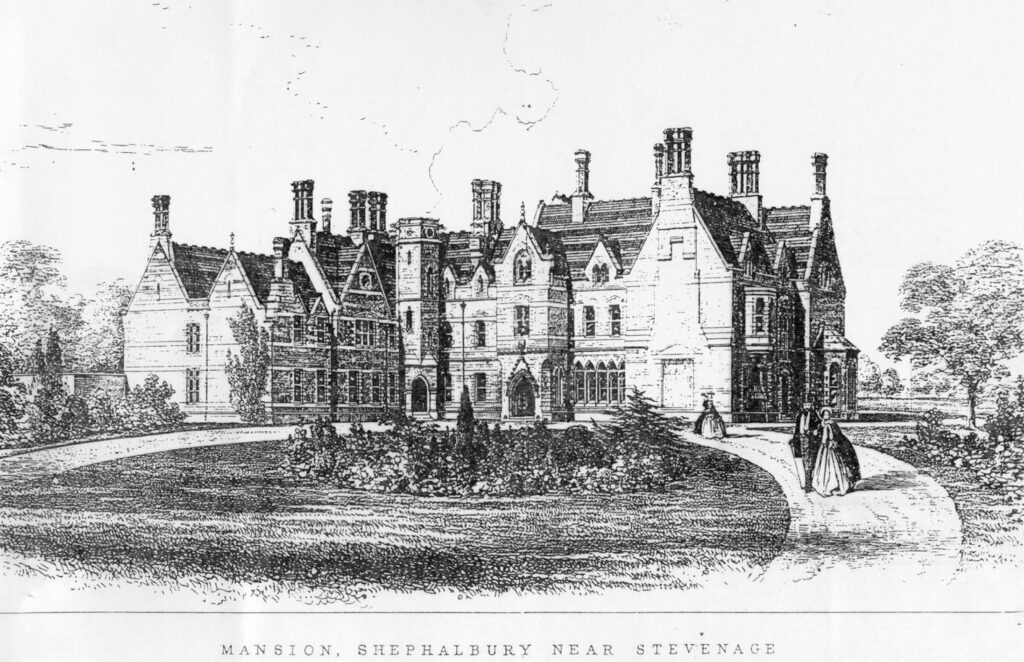

Samuel was succeeded as owner of Shephalbury by his son Unwin Unwin Heathcote, who finally paid the Wrights’ outstanding bill for malt and hops: £104 4s 6d is worth around £11,500 today, not a small sum. Unwin Unwin had the old manor house pulled down, and a neo-Gothic pile erected about 1864-5. Presumably the old manor house brewery disappeared together with the old manor house.

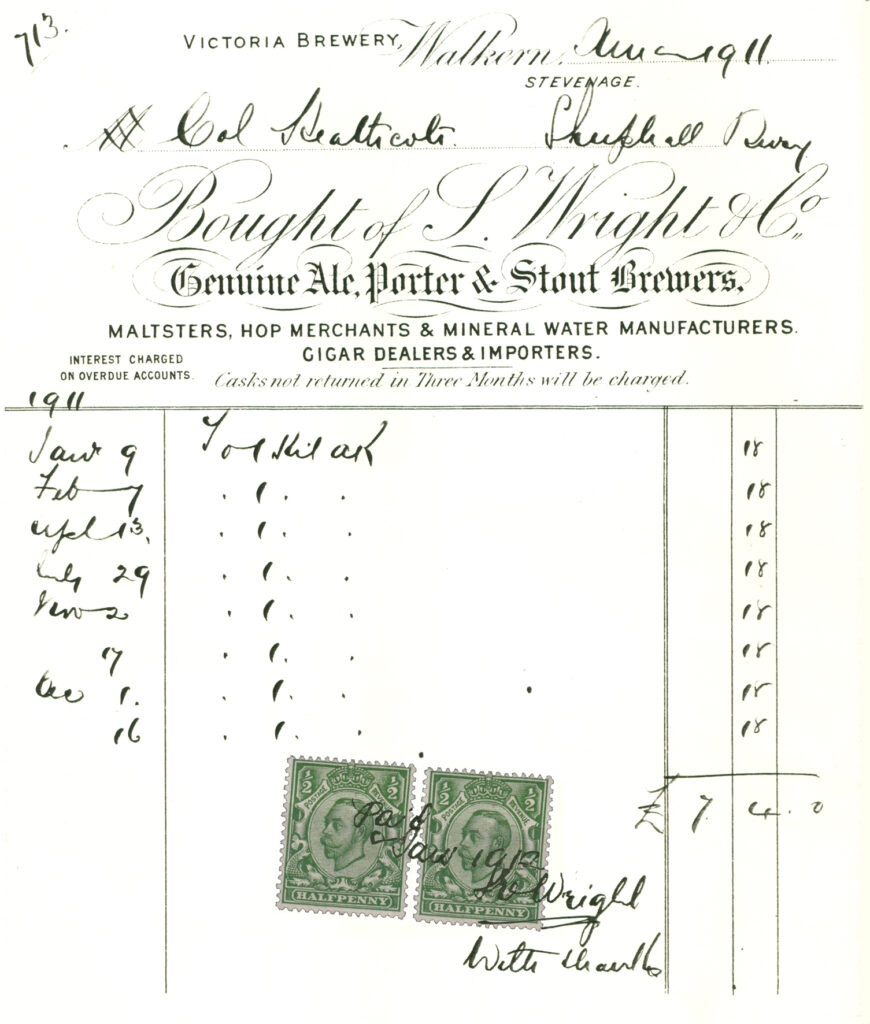

However, Wright’s association with the Heathcotes continued for at least another 50 years, as this second invoice shows. “Colonel Heathcote” was Alfred Unwin Heathcote, Samuel Unwin Heathcote’s grandson, and a colonel in the Royal Engineers. In 1911 he ordered eight kilderkins of Wright’s AK, at a shilling a gallon, which would have been a light bitter of around 1045 OG, four or 4½ per cent abv. The 1911 census shows the Shephalbury Manor household had eight servants, including a groom and a footman. Eight kilderkins works out at a pint a day just for Alfred and the two male servants …

Going back to Samuel, if he, or rather one of his servants, was brewing 96 barrels of beer a year, that works out at eight barrels a month. If he had a two-quarter brewery, that is, one capable of mashing two quarters, 650 pounds or so, of malt at a time (a reasonable assumption, I think, judging by the sizes of small commercial breweries in Hertfordshire in the 19th century), then he was brewing only once a month, at an average of four barrels to the quarter, to give a beer of six to seven per cent abv.

Clearly it would not take much of a step up to increase output considerably: brew once a week, and you are now making almost 420 barrels a year, which you could retail for almost £1,000, at 48 shillings for a barrel of XXX. That’s a fairly staggering £110,000 a year in 2024 value, a healthy addition to a farm’s income.

Given those figures, it is not surprising to find that a fair number of farmers who brewed for themselves and their workers did indeed cross over into commercial brewing. In Hertfordshire they included the Fordhams of Ashwell, whose brewery lasted until 1952, their neighbours in Ashwell Christy and Sale (brewery closed 1921), William Rayment at Furneux Pelham (brewery closed 1987), Thomas Wild at the Mill End brewery, Rickmansworth (brewery closed 1900), the Clark family at the Hyde Hall brewery, Sandon (closed 1899), and Samuel Wright in Walkern (brewery closed 1924), plus eight or nine smaller concerns often connected to an inn as well. What the figures are nationally for farmers becoming commercial brewers I don’t know … anyone want to do the research?

Shephalbury Manor today, incidentally, is surrounded by the now not so new town of Stevenage, where I grew up (Shephalbury Park, where I played football and cricket as a child, is about a third of a mile from my old home) and is now owned by the Coptic Orthodox Church, and the Coptic Orthodox Cathedral of Saint George has been built in its grounds. I wonder what Samuel Unwin Heathcote, a committed opponent of the Roman Catholic church and a strong promoter of Protestantism, vice-president of the Hertfordshire Reformation and Protestant Association, financial backer of the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, would think of the gospel as promoted in foreign parts setting up in his old home …

invoices reproduced courtesy of Andrew Cunningham

Great research as always, Martyn – very interesting.

Thank you Rod, I always hope so – although to be honest my main criterion is always “do I find this interesting …”

Excellent!

I’ve seen early sales (1810-1840) from brewers to the public in accounting ledgers for “malt dust”, I have wondered what use it had in the home or perhaps garden. I have also seen at Pennsbury Manor the county home of William Penn, very large tuns and coppers ( maybe 10 bbls) for brewing from the mid 18th century . Clearly, every man his own brewer.

When the Knebworth area had an influx of Scottish tenant farmers after the (for Hertfordshire) bad years in the late 19th century, one of the incomers, Mr Drummond at Broadwater at the junction of the road for Shephall was well-known for having a cask of whisky always on his table.

My great uncle used to drink Wright’s beer in the Marquis of Lorne in Stevenage before Wrights got out of brewing. Many years later I asked him in the late 1980s what Wrights beer was like. He said ‘Even worse than McMullen’s’)

Thanks for that, Hugh … hope you’re keeping well …

A further thought. Are any of the buildings at the Shephall Bury farmhouse likely to have been the brewhouse? Whilst the manor house was demolished in the 1860s the farmhouse (a baffle-entrance, central-stack, late 17th Century building almost identical to the northern part of the White Lion Hotel in Stevenage) still stands today.

Unfortunately the expert on this part of the world, Mary Spicer, was carried off by the Coronavirus.

Also, have you looked at the farm brewery at Newnham which was I believe was killed off by Hitchin historian Reginald Hine’s father (see rueful comments of a villager in Herbert Tompkins Highways & Byways of Hertfordshire)?

Time I headed off to the only Stevenage pub whose farmyard is now a park…

Funnily a number of breweries in Ireland are owned and run by farmers three of which include Brehon brewhouse, Ballykilcavan and Heaney Brewery.

I imagine his lordship would have less been bothered by a Orthodox cathedral occupying his land than if it were a Catholic one

This was interesting! The scale at which he was operating is definitely bigger than a “classical” farmhouse brewer, and, as you say, close to a small commercial brewery.

I’ve been wondering if, in between commercial brewing and farmhouse brewing, there is a third sort of brewing: manorial brewing. What Pamela Sambrook described in her book is one of the things that made me think in those terms, but there was also manorial brewing in Sweden, for example.

I suppose one could enlarge it a bit by calling it “estate brewing”, and include brewers at ironworks, castles/army camps, and so on as well. Basically, anyone brewing for a relatively large estate.

Your assumption that they brewed once a month is also interesting: Sambrook has a paper I never managed to get hold of titled “The Once-A-Month Brewer”, which fits nicely.

very interesting . your article confirms my retirement. I retired retired from work seven years go. I home brewed a 5 gallon batch every week for a year. 5 gallons a wk = 37 pints a wk, which is 1900 pints a year. all these pints were freely distributed. None were returned.

[…] one with wood paneling finish is a big bonus. Stepping back from that dailiance with the modern, Martin is back with a bit of a calculation on how much beer did a 1860s farmer brew for his operational […]

I would love to have numbers on how much beer was being brewed by these domestic brewers in the first half of the 19th century.

Given that, in the early 1800s, a there were thousands of publican brewers, there was plenty of commercial brewing that was probably on a smaller scale than at a large country house. It must have added up to a considerable quantity of beer produced non-commercially.

Another interesting and enjoyable post. I assume Heatcote School was named after ( or in someway linked to ) the Heathcotes mentioned here ?

I lived in Stevenage in the early 80s, when teaching at Collenswood School. Most Fridays in term-time the science lab teachers ( myself included ) would take lunch at a McMullens pub in nearby Aston ( name sadly forgotten ) where I usually drank the AK ( last tasted in London at the Spice of Life, and enjoyed too. They referred to it as an amber ale at that point). I doubt if current school practice would allow lunchtime drinking now. However, my local was The Roebuck, which looks like it still exists. The Marquis of Lorne I recall as a Greene King pub at the end of the High Street in the Old Town. A long time since I have been there.

Should let the 6th years (final year in secondary in Ireland) continue the tradition every Friday