Today, November 8, marks 150 years since the Fuggle hop first went on sale, in a field in Paddock Wood, Kent, after Richard Fuggle and his brothers Jack and Harry had spent ten years propagating the variety until they had enough, 100,000 sets, to sell commercially.

Their hop, found growing in a flower garden around the year 1861, went on to be easily the most popular variety in Britain, and has been grown by hop farmers around the world, from Oregon to New Zealand, via Slovenia.

The Fuggle is also an ancestor of more than 30 different other hop varieties, including some of the best-known hops used by craft brewers.

Despite being perhaps best-known for its use in classic British milds and bitters, the Fuggle is actually one of the most versatile varieties around, having been used in top-selling lagers and world-famous stouts.

Track down a brew using Fuggles today, and raise a glass to one of England’s great contributions to the world of beer.

Eleven amazing facts about the Fuggle hop (number six will make you grin)

1 The man who discovered the first Fuggle hop growing in his flower garden 160 years ago, George Stace Moore of Horsmonden, Kent, was the uncle of the hop farmer who brought the variety to market, Richard Fuggle junior of Old Hay, Brenchley, Kent

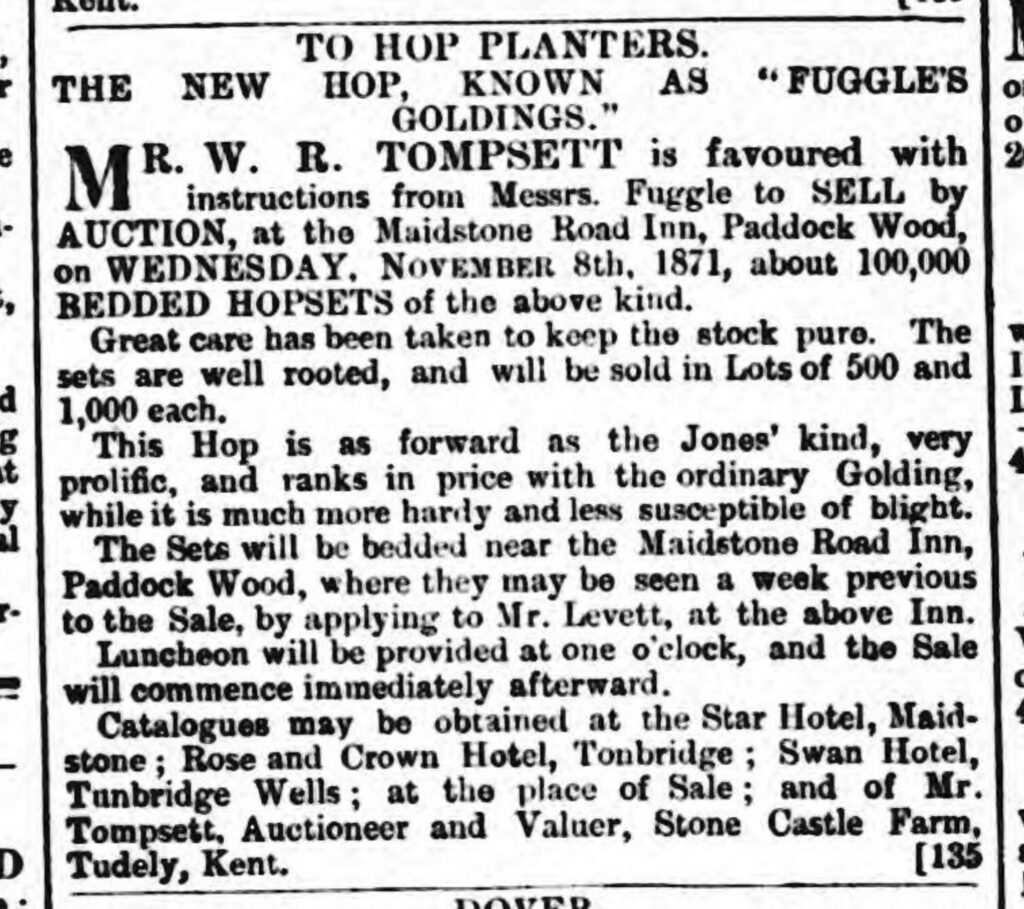

2 Richard Fuggle thought his new hop was a variety of the Golding hop, and called it “Fuggle’s Golding” when he launched it 150 years ago. Later researchers decided the two hops could not be related, because the Fuggle includes farnesene among its oils, which Goldings do not. But genetic research in the Czech Republic in 2019 proved that Goldings and Fuggles hops are indeed closely related, either mother-daughter or grandmother-granddaughter.

3 This early belief that the Fuggle was a variety of the Golding is the reason that the Fuggles hops introduced into Slovenia in the 1880s were grown as “Styrian Goldings”.

4 Fuggles hops were first grown in the Pacific North West in 1892

5 Guinness was a big buyer of American-grown Fuggles hops in the 1920s for use in its stouts.

6 A mix-up on an American hop farm meant that a batch of Fuggle hops was distributed to other farmers mislabelled “Tettnanger”, and this “US Tettnanger” became very popular, with, for example, Anheuser-Busch using large quantities in Budweiser, until the error was finally recognised and “US Tettnanger” relabelled Fuggle.

7 Similarly British brewers in the 1950s were importing Styrian Goldings for use in the lagers they were starting to brew, not realising it was the same hop they were putting into their milds and bitters.

8 In 1950 Fuggles made up almost 78 per cent of the English hop crop. The variety’s susceptibility to Verticillium wilt, however, saw acreage crash, and today only around a dozen English hop growers plant the Fuggle.

9 Willamette, a popular hop variety among craft brewers in the US, is simply a triploid version of the Fuggle, its genes manipulated so that it is sterile, and produces no seeds.

10 The Fuggle is also in the ancestry of many other hops popular with craft brewers, including Cascade, Citra and Centennial, Nelson Sauvin and Huell Melon.

11 The Fuggle is now the third most widely grown hop variety in France.

The current trendy preference for American hops is badly damaging the English hop industry, so it is ironic indeed that many of the most favoured “American” hops are so closely related to the humble Fuggles. As a former brewer, I consider Fuggles a most under-rated and versatile hop, being good for bittering and aroma. If you can get Fuggles fresh enough, and use leaf not pellets, you can get a wonderful, almost orangey flavour from them.

I wish small breweries in this country would use traditional varieties like Fuggles and Bramling Cross more than is presently the case.

Thank you Martyn for this and all your posts. Reading your posts is one of few times I access the internet and leave being smarter (not dumber) for it.

I’m with Rod, I don’t like these American beers.

Luckily my homebrew antics mean I can supply my own demands & I heavily favour bitters & UK pale ales, using Fuggles, East Kent Holdings & Bramling Cross. I do occasionally try others, but find myself going back to my trusted trio.

Does anyone know what the sizes of US crops of Fuggles (or similar varieties like Willamette) were like in the decades following introduction in thhe 19th century?

I know in a lot of recreations of old US beers the assumption is that hops in the recipe are Cluster, but I’m curious if Fuggles crops were significant enough that they might be strong possibility.

There were 10,000 pounds of Fuggle hops harvested in the Willamette valley in 1893, and an little less than 100,000 pounds in the whole of Oregonj in 1905, but that was less than 0.5 per cent of the total state hop harvest. By 1929, however, Oregon was growing around 1.6 million pounds of Fuggles a year, which was around 10 per cent of the total. So while Fuggles were certainly available, Clusters were still easily the most popular.

[…] Happy Fuggleversary, 150 years since the birth of a classic hop […]

Hi Martyn, further research has added a twist to the “origins of the Fuggle” tale.

The origins of the Fuggle haven’t changed, but the long held belief that Richard Fuggle (junior) was of Fowle Hall, Brenchley, may have been correct, in an odd way.

It appears that Richard Fuggle jnr. moved his family from (West) Old Hay Farm to Fowle Hall in 1872 and stayed there with his uncle, Thomas Fielder Fuggle, for 2-3 years before moving to Owley Farm in Wittersham in about 1875. The Old Hay estate was sold off during 1871 and 1872, which included West Old Hay Farm, East Old Hay Farm, known collectively as Great Old Hay, and Little Old Hay Farm.

In 1901, Messrs. Noakes and Larkin, had stated to Prof. Percival, that the hop was first marketed ‘around’ 1875, which pretty much falls into the time when Richard Fuggle jnr., ex of Old Hay, was residing at Fowle Hall.

That would explain why he was specifically identified later as Richard Fuggle of Fowle Hall. Wrongly and rightly in a way.

Thank you, Lionel, that’s very interesting indeed. Keep up the great work – historians of beer are astonishingly grateful to you!