I was flattered to be asked to take part in one of the virtual symposiums (symposia?) at the Chicago Brewseum’s Beer History Summit last week, the panel I was on discussing “A History of Hops in the Western World”, and my particular brief being to talk about “An examination of hop production and use in developing and stylising British ale from the 15th-19th centuries”. It’s an interesting topic, because in fact there’s very little to talk about.*

If that sounds paradoxical, it’s not: from a 21st century point of view, the surprise is how small a role hops played in the development of British beer styles before the 20th century. The hops, in themselves, were pretty irrelevant, with perhaps the single exception that Goldings, as THE premium hop, were regarded as the hop to use in the most premium beers, such as IPAs. But apart from that, the concept of “hop variety” itself was scarcely developed, as far as brewers (but not growers) were concerned, and there was certainly no idea of a particular variety for a particular style, and, it seems little idea of specifying varieties, as against geographic origins, for types of beer.

What brewer were – almost entirely – concerned with was where the hops came from, rather than what variety they were, and since even in somewhere such as East Kent there were likely to be at least three different varieties growing, specifying “East Kents”, as brewers often did, meant you might get Goldings, or Jones’s, or Grape hops. For growers, varieties WERE important, but the importance of variety was not connected with flavour so much as yield (the fundamental and most important aspect as far as hop growers were concerned), suitability to particular terroirs, susceptibility to various forms of disease and pest and other aspects of what was, above all, an agricultural product, and one susceptible to wilder swings in annual production, and therefore price, than probably anything else that farmers could grow.

Hops were (and are) a crop whose yield could vary enormously from year to year depending on growing conditions and infections of insects and blight. Price and availability were thus major influences on brewers’ purchases of hops, and they would frequently buy excess stocks in times of glut, when hops were cheap, for fear of not being able to find enough hops in subsequent years of blight. Their expressed preferences for particular geographical locations, however, rather than specifying particular varieties to maintain particular recipes mean that until the beginning of the 20th century brewers bought on terroir, where the hop was grown, rather than variety, and it was terroir that dictated price: Essex hops, for example, sold for less in the 1770s than Kent hops. Farnham hops were, for a long time, the most prized: new Kent hops were selling for 42 shillings to 70 shillings in May 1781, while new Farnham hops went for 53 to 85 shillings a pocket.

Another important determiner of price, and an indication of how brewers had very little understanding of what exactly it was that hops contributed to beer, and what they outght to be looking for, was greenness: Pale green hops were prized, particularly for pale ales. A note on the hop market in London in September 1776 said: “The demand is for hops of colour.” In September 1784, hop-growers in Hereford were complaining that while the crop that year was going to be “great”, “the very plentiful rains lately had not done them much good, in that there will be very few hops of colour.” Hops were referred to as “fine”, “good”, “ordinary” and “middling”, but no variety was mentioned.

Brewers of pale ale looked for aroma in hops, but in a parliamentary debate in April 1774 on a proposal designed to set a minimum weight for hop bags and sacks, to prevent fraud, Samuel Whitbread, the great London porter brewer, told fellow MPs that he had kept hops in lightweight bags for ten years, underlining how little hop aroma meant to porter brewers, at least.

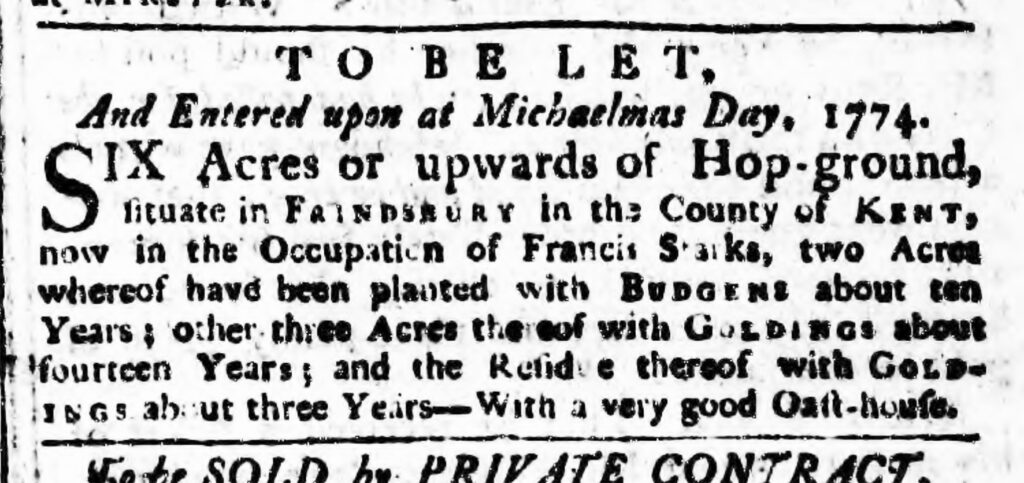

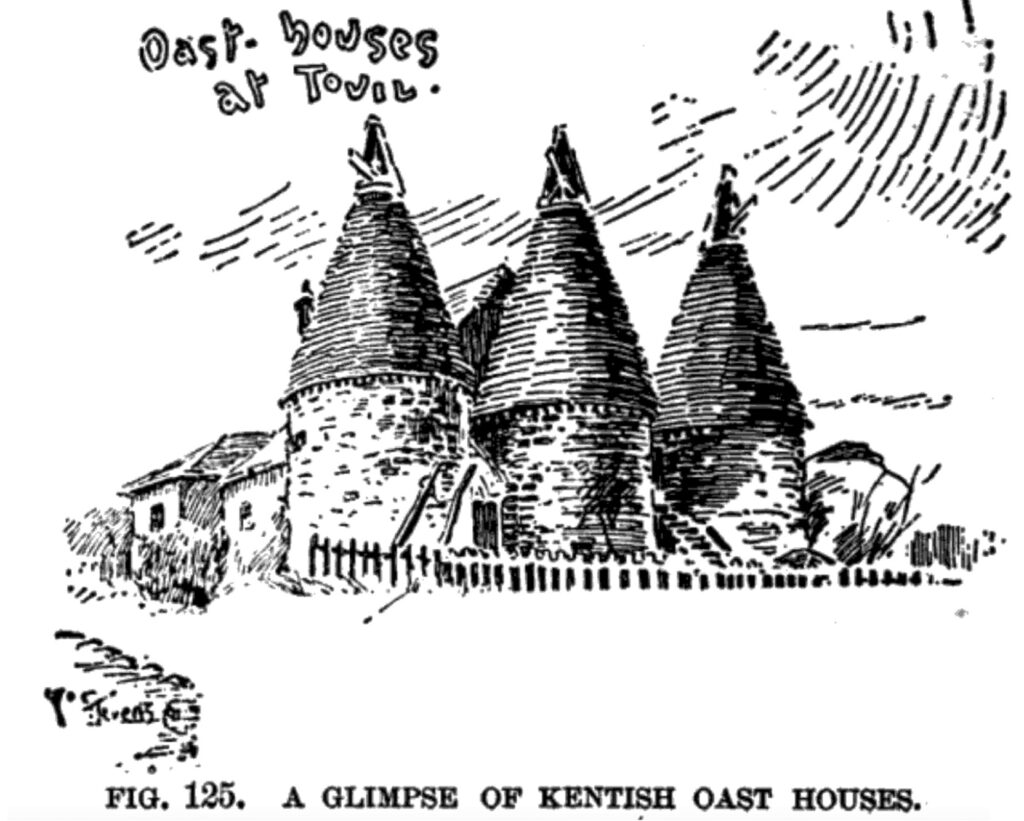

Certainly there were particular named varieties that were prized, among them Goldings, and we know, from an advertisement in the Kentish Gazette in August 1774, that Goldings were around since at least the 1750s. By 1794, according to a writer called William Thomas Pomeroy, they were being grown in Worcestershire, and together with the Mathon white hop, a local variety named for a village on the Herefordshire/Worcestershire border, were “in particular esteem, both with the planter and merchant”. But while they, and other named varieties , are mentioned in books and publications directed at growers and farmers, it was rare for books on brewing to recommend specific varieties.

One of the few, from 1825, The Farmer, Maltster, Distiller, and Brewer’s Practical Memorandum, by J.S. Forsyth, bigs up the Mathon white hop from Herefordshire, saying it “not only preserves ale better than any other, on account of affording more extractive matter, but is also much more salubrious, on account of the bitter principle being less pungent … We therefore advise those who are desirous to make a wholesome and pleasant ale to employ the Mathon white hop in preference to any other.”

Another of the few brewing manuals from before the 1890s to mention named varieties of hops was The Art of Brewing and Fermenting, published in 1836 by John Levesque, a practical brewer who had worked at Mackeson’s of Hythe, in Kent, and later at the Anchor brewery in Old Street, St Luke’s, on the northern edge of the City of London. Levesque said Golding hops were “of a rich and delicate flavour” He also named Canterbury Grapes, “a very good and useful hop”, and North Clay hops from Nottingham, “a strong and rank hop, fit only for porter-brewing, when mellowed by age.”

Apart from that suggestion, Levesque’s only other recommendation as to types of hops to use for different styles of beer was to say: “Suit the colour of the hops to the colour of the beer. The ripest hop are always the brownest, and best adapted for porter-brewing … use brown hops [that is, old ones] for brown beer, and pale-coloured hops for all pale beers.” Emphasising the brewer’s belief in the importance of terroir, Levesque added: “The soil alters the quality of hops, as it does other plants, and will sometimes alter their appearance so much as to give them the face of a different variety.”

Levesque cared so little about hop varieties in so far as they affected recipes, in fact, compared to terroir, that he advised “the young brewer and practitioner” to keep a “book of record” in which records were kept, when hops were bought, of the grower’s name and the district and parish where the hops were grown, “to find out those growers whose fame stands high in the management of hops, and likewise to ascertain those parishes, in every district, in which the best hops are grown” – but not apparently, to bother to find out what the actual variety of hop used was. It is doubtful, in any case, if Levesque’s naming of hops was useful for 19th century brewers: in 1857 Charles Leney, a hop grower and brewer from Wateringbury in Kent, declared that “very few brewers know a Golding hop from a Grape”.

Leney was giving evidence to the Parliamentary Select Committee on Hop Duties, where there was plenty of discussion by growers of different hop varieties, but the evidence confirms that while brewers might ask for, say, Goldings, much of the buying was still done on terroir, rather than variety: Mid and East Kent was preferred by those wanting a superior hop, Worcester less so and Sussex not much at all.

Among those giving evidence was a Worcestershire hop grower, John P. Smith, whose customers included Bass, and who said he grew six different sorts of hop: Goldings, Mathon whites, Cooper’s whites, Grapes, Jones’s and “a light quantity of Colegates”. The comparative prices, taking Goldings at 100, were Mathon whites and Cooper’s whites at 95, Grapes and Jones’s at 86 to 90, and Colegates “about the same as Jones’s”. The Colegates were heavy croppers, producing twice as much per acre as other hops, but “a bad bitter; they are powerful hops but … not desirable for the brewer.”

A Weald of Kent hop grower, Robert Tooth, who had been in the business 40 years, told the committee that in his district the main hop varieties were Grapes, followed by “some Jones’s and some Colegates”. In Mid-Kent “they have the Goldings, and they have a superior type of Grape hops called the Canterbury hop,” while in East Kent it was “one third Jones’s, one third Golding’s hops and the other third Grapes.” Brewers asked for specific varieties, but “in many instances” brewers were not able to judge the hops they were being sold, and while “some” would know that they had been sold, for example, Jones’s instead of the Goldings they wanted, many of the larger brewers only bought hops once a year, and it was “very difficult” for them to know Goldings from Jones’s. He also complained that the quality of hops was not as good as when he was “quite a young man”, when “the Mid and East Kent Golding hop was like a nonpareil; it would scent the room. Now we do not find that quality.”

Tooth said that “high-priced Bavarian hops” were “a mild but strong bitter” that was “a superior article to the East Kent hop” and “very suitable for the East India ales”. He was backed up by the Burton upon Trent brewer Michael Thomas Bass, an MP and a member of the committee, who agreed that Bavarian hops were superior to English ones, and said that his own brewery tried to buy Bavarian hops, though they were generally too dear. Otherwise, he said, Bass bought “principally the best quality from Mid and East Kent”, and “a few of the finest Worcestershire hops”, but never from Sussex. However, he said, if it was not for the high price of Bavarian hops, Bass would be happy to brew solely with Bavarians: instead it mixed the Bavarian hops it brought with English hops. The conclusion has to be that if it were not for the high price of hops from southern Germany, the classic flavour of a Burton IPA would be derived from Hallertauer Mittelfrüh rather than East Kent Goldings.

Bass and Tooth (who was a brewer as well as a hop grower, and whose sons were brewers in Australia) never spoke of the hop varieties that they used in their beer, or in any way indicated that variety was more important than geographical origin, saying only that they used “the best” or “the very best” hops, from specific localities. (Tooth also revealed that hops up to 20 years old were sold under the name “old olds”.)

The lack of understanding of varieties was demonstrated by a Southwark hop merchant called Thomas Waterman, who gave evidence to the committee about American hops, and blamed their “peculiar” flavour on “the soil on which they grow”, rather than their being a different variety. (I’ve mentioned Mr Waterman before, and his – to 21st century beer drinkers – amusing belief that American hops “would never come into use in England for brewing purposes, on account of [their] flavour”.)

However, a couple of years before the parliamentary committee met, the Scottish agricultural chemist James Finlay Weir Johnston had published a book called Chemistry of Common Life which discussed hop varieties and the types of beer they were suitable for. It is worth quoting him (almost) in full:

“Of the cultivated hop, there are many varieties; but in our principal English hop districts, Kent, Surrey and Sussex, only about five varieties are principally grown. These are:

The goldings, grown chiefly in middle and east Kent. They delight in a rocky, calcareous soil, or a rich, friable loam. They thrive only in the most naturally fertile kinds of soil.

The white-bines are the favourites of Farnham and Canterbury. They require the same description of soil as the goldings. Are very similar in their appearance and growth, and have nearly the same value in the market. The flower of the white-bines is considered to possess the most delicate flavour, while that of the goldings is thought by some brewers to have more strength. These two varieties are most esteemed for the brewing of pale bitter ale.

The jones’s stand next in favour with the brewer. They will grow on inferior land; and as they require very short poles, and are pretty good croppers, they are in general favour with many growers in Kent.

The grape has many sub-varieties and requires longer poles than the Jones’s … [it] delights in stiff, heavy soils … and produces very heavy crops. Hence its prevalence in the Weald. It is commonly used for the ordinary sorts of beer.

The colegate is a smaller variety of hop that the grape, but produces enormous crops in Sussex and the Weald. It is often surreptitiously passed off in the market as goldings; but is greatly disliked by the brewers on account of the rankness of its flavour. It is looked on by many as the worst hop that is grown.”

Despite this discussion of varieties of hops, much of Johnston’s commentary was still based on terroir, the idea that hops grown in a particular locality had a common flavour and character regardless of variety. He discussed the hops grown around Retford in Nottinghamshire, known as North Clays because of the stiff clay soil where they grew, and declared them “preëminent in rankness. They give a course flavour to beer, which is almost nauseous to those unaccustomed to it.” The answer, Johnston suggested, was not to plant a different variety, but “Probably a more thorough drainage of this district would improve t he quality of its hops.”

Similarly, Johnston praised hops from Worcestershire without naming any varieties apart from Kent’s best-known, instead emphasising the terroir, the soil in which they grew:

“The Kent hops … are disrelished by those who have been accustomed to the still milder flavour of the Worcester hops. They excel in this respect the best Kent goldings, and are usually very taking to the eye. In practice they are found to ripen beer sooner than any other variety of hop. They grow on the red soils of the vale of Severn, and in the opinion of beer-drinkers, possess a grateful mildness not to be found in any other hops. Hence, in Lancashire, Cheshire, and some other counties, where the taste for the Worcester hop exists, even fine Kent hops would be rejected as unsaleable. A nice Lancashire beer-drinker calls beer hopped with Kent hops porter-ale.

(Those last couple of sentences, incidentally, were a slightly re-written steal from John Richardson’s Theoretical Hints on Brewing, published almost 70 years earlier. Plagiarism in old brewing texts is common)

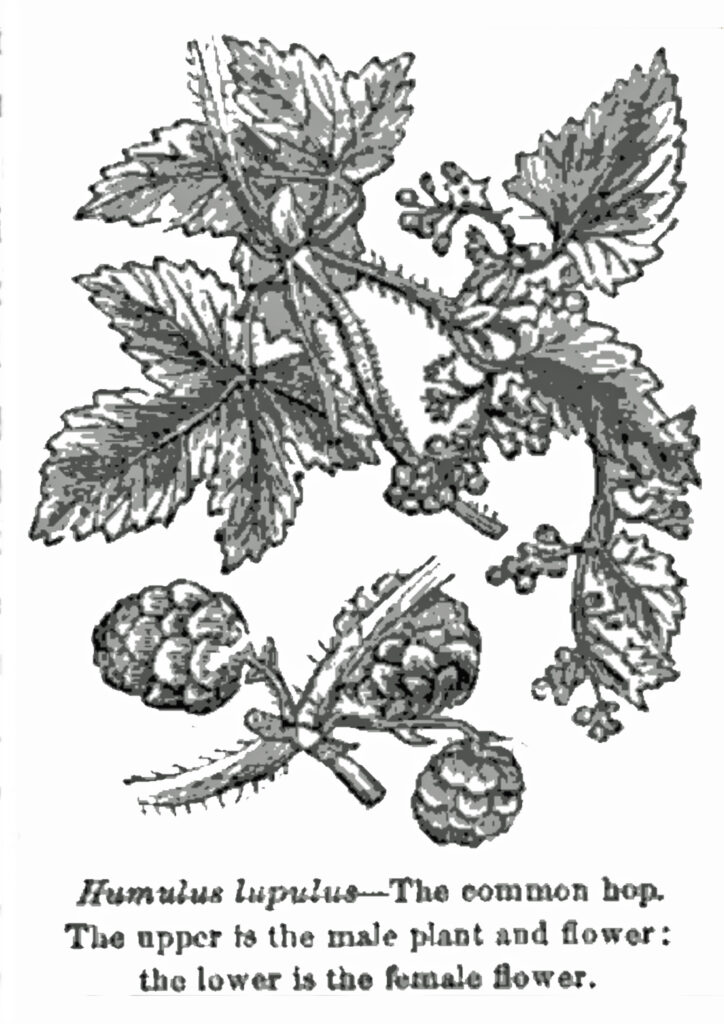

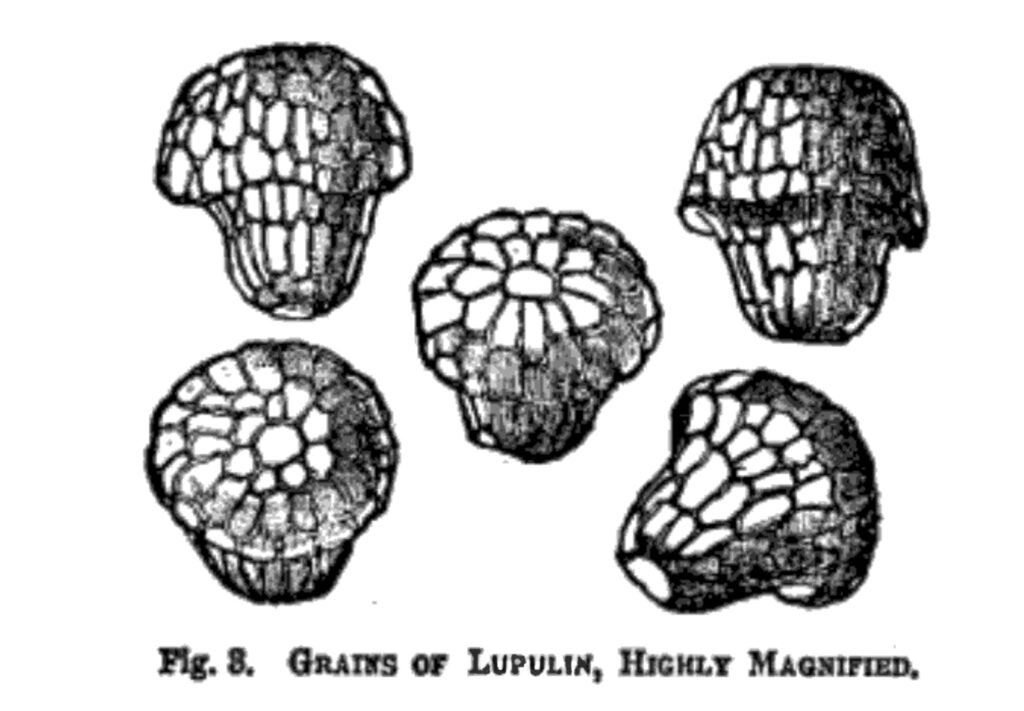

What is also surprising is that lupulin, the soft resin that contains practically everything that a brewer wants from a hop, from aromatic oils to alpha acids, had been discovered and named in 1820, by a 33-year-old New York doctor called Ansel Wilmot Ives, and yet growers and hop buyers seem not to have acted upon this and sought the hops with the highest quantities of lupulin for decades after Dr Ives worked out what this yellow powder in the bottom of a bag of old hops was, and what it did. In 1835 the leading brewers of New York and Philadelphia, including Matthew Vassar and Frederick Gaul, complained that 15 years on from Dr Ives’s discoveries, too many brewers were still buying hops on colour, and insisting that if they were being used for pale ale they should be green, which meant that the hops were being picked too early, before the lupulin had formed properly in the hop cone, and were thus useless for brewing good beer.

Despite this, it is as hard to find mentions of lupulin in brewing books before the 1890s as it is to find named hop varieties. In 1867, William Loftus, a London-based author whose book The Brewer went into several editions (although Loftus was a maker of saccharometers and the like, rather than a brewer) was talking about hops in terms of their place of origin rather than their variety. He gave a recipe for a strong pale ale of 1062 OG that used a mixture of one third each Bavarians, Farnhams and East Kent, dry-hopped when racked into casks with one pound per barrel of a mixture of 50/50 Bavarians and Farnhams or East Kents. For porter and stout, Loftus recommended “strong and thick blossomed” hops, “dull in colour and of well matured growth”, that had been stored for eight or ten months, as “when new they do not yield their bitter apart from harsh and disagreeable extracts.” But he did not specify which hop variety found in East Kent those “East Kents” should be.

In 1885, six decades after Dr Ives’s discoveries, the consultant brewer Edmund Richard Southby still had to complain that brewers were continuing to buy hops on the basis of their colour rather than their “more sterling qualities”, making their pale ales with “thin, weak, but light and brilliant hops, which, though commanding the best prices, contain so little condition [that is, lupulin] that every full brewing quality is sacrificed to colour.” However, Southby also noted that different scientists had arrived at very different analyses of the constituent parts of lupulin, and his own experimental findings did not match those of others. Nor does he make any reference to the different level of extract available from different hop varieties: and his only mentions of varieties are of Goldings, “Worcesters” and Spalt (the last of which, he suggests, could be used for dry-hopping export ales …)

Southby’s big rival in the consultant brewer business, Frank Faulkner, writing at almost exactly the same time, still placed considerable emphasis on terroir as a major influence on hops, saying that “much depends on the exact constitution of the soil upon which they are grown.” However, he added that the value of hops “depends mainly upon their colour, freedom from leaf intermixture and mould, and their richness in that yellow powder (or technically, ‘condition’) which covers the seeds and contains the whole of the constituents which are of service to the brewer,” putting “condition” – lupulin – after colour, but recognising its importance. Faulkner listed geographical origin, but, mostly, not variety, as important when choosing hops, saying of brewers’ preferences: “some [give] the preference to the mild Worcester hops, others to varieties of Farnham, while many of our porter brewers are fond of the peculiar-flavoured Americans,” and, a little later in the same chapter, “As for flavour, each judge has his own special proclivities, the majority preferring the ‘Goldings’ of middle and East Kent, others the ‘white bines’ of Farnham; while another section consider the finer descriptions of Worcester hops preferable for delicate-flavoured beers.”

It was not until the start of the 20th century that any major brewer, in the UK, at least, seems to have started seriously buying any variety other than Goldings by name, rather than geographical origin. Guinness bought most of its hops from England for a very long time: in 1842 all its hops came from Kent. It bought small amounts of Bavarian hops in 1853, and it was buying American hops by 1858. From then the buying policy was “one third English, one third Bavarian, one third American”. By the late 1890s brewing scientists such as Lawrence Briant were finally working out that it was the soft resins in lupulin that gave hops their preservative power. But it seems to have taken some time for brewers to come to the realisation that some hop varieties naturally contained more soft resins than others, and those that had the most soft resin were not necessarily the most expensive, or those most generally admired. Eventually, from 1910, Guinness largely dropped the Goldings it had been buying, the previous policy having apparently been that it was a producer of a premium product and therefore it should buy premium hops, and started buying Fuggles instead, on the realisation that the cheaper Fuggle hop contained as much or more soft resin, but at a better price per pound.

This looks to be the start of real “variety awareness”, helped by increasing analysis of the constituents of hop varieties by people like Ernest Salmon at Wye College in Kent, so that when George Clinch wrote his book English Hops in 1919 he listed 25 different varieties with descriptions such as “Lupulin is scarce but the flavour is fair” for Henham’s Jones’s, “well furnished for lupulin” for Rodmersham and “full of lupulin” for Mathon whites. The difference between attitudes pre- and post-First World War is shown in the book Brewing and Malting by John Ross Mackenzie, published in 1927. This is basically a rewrite of H. E. Wright’s 1907 Handy Book for Brewers, but by now both Guinness and Whitbread had bought hop farms in Kent, and Mackenzie puts in a three-page discussion of hop varieties, with descriptions of 16 different hops: the first book for brewers I have found that goes into such detail about hop varieties. Varieties, clearly, are now at least as important as terroir for brewers, which Mackenzie discusses, but does not play up.

I don’t have the sources to say what happened over the next 40 or 50 years, though my impression is that English brewers still bought hops, and/or recorded them in brewing books, by geography rather than variety for quite a long time. It would be fascinating to know when brewers actually decided: “The recipe for our best bitter is 50 per cent Goldings and 50 per cent Fuggles”, rather than “50 per cent East Kents and 50 per cent Worcesters” or whatever, and if anyone has an answer to that, do let us know.

*And yet I go on for more than 3,500 words …

Hop breeding only started in the early 20th century and it was only after the First World War that newly bred varieties of hops became available. Before that hops varieties were landraces that came from taking cuttings from the best hops growing in an area. All hop varieties are essentially clones of a single female plant. Canterbury Whitebines and Mathons originated as cuttings from Farnham Whitebines, and Goldings came from a ‘bud sport’ mutation improving on Canterbury Whitebines. The Farnham Whitebine growers did protect the premium nature of their product by banning Farnham based growers of the red bined “Neverblacks” from selling at their booths at Weyhill Fair.

Before Salmon’s hop breeding programme new varieties grown from seed were almost always of worse quality than selected landrace varieties. Some more scientifically minded brewers embraced Salmon’s work, particularly JS Ford of Youngers brewery. Salmon must have appreciated the support as he named a hop variety John Ford.

[…] This set the stage for some evening reading when Martyn Cornell expanded on what he said last week during the Beer Culture Summit. A quick summary: “From a 21st century point of view, the surprise is how small a role hops played in the development of British beer styles before the 20th century.” Now go read it. […]

[…] Cornell asks “How important were hop varieties to pre-20th century brewers?” You’ll know the answer to this if you’ve ever looked at any old brewing […]

Sometime around 1914 Barclay Perkins started recording the variety as well as the region of origin. But only sometimes. It wasn’t until the late 1920s that they always listed the variety.