Serendipity – I love it. I was searching for something else entirely when I came across this advertisement in a Kentucky newspaper, which is how I discovered that the first successful keg beer in Britain was called Flowers Keg because an English teenager successfully led an armed posse in Illinois in the early 1820s against a gang of slavers who had kidnapped some “free” blacks and were planning to sell them in the South.

Let us begin at the beginning. I knew about Richard Flower because he is an important figure in the history of brewing in Hertfordshire, and I knew he had moved to Illinois to join his son George, who was one of the pioneers in developing what was called the “English Settlement” in the territory, which developed into the city of Albany. But I didn’t know that Richard, who was born in London, had trained at Whitbread

Richard had run his own brewery in what is still called Brewhouse Lane, Hertford, 20 miles north of London, between 1785 (when he was aged 23 or so) and 1803, initially in partnership with a man named John Fordham, a member of an old-established family of farmers and landowners from the North Hertfordshire/South Cambridgeshire area. (The “brewery tap”, originally an inn called the Three Tuns, is today a Thai restaurant.) On Christmas Day 1789, Richard married John Fordham’s sister Elizabeth in St Andrew’s Church, opposite Brewhouse Lane. He stayed at the brewery until 1803, when he sold it to two maltsters from Baldock named Fitzjohn and went off to be a farmer at Marden Hill, two or three miles to the west. (Coincidentally, the man who stood security for the Fitzjohns in their purchase was James Ind, whose son would become the founder of a successful brewing business in Romford. Essex …)

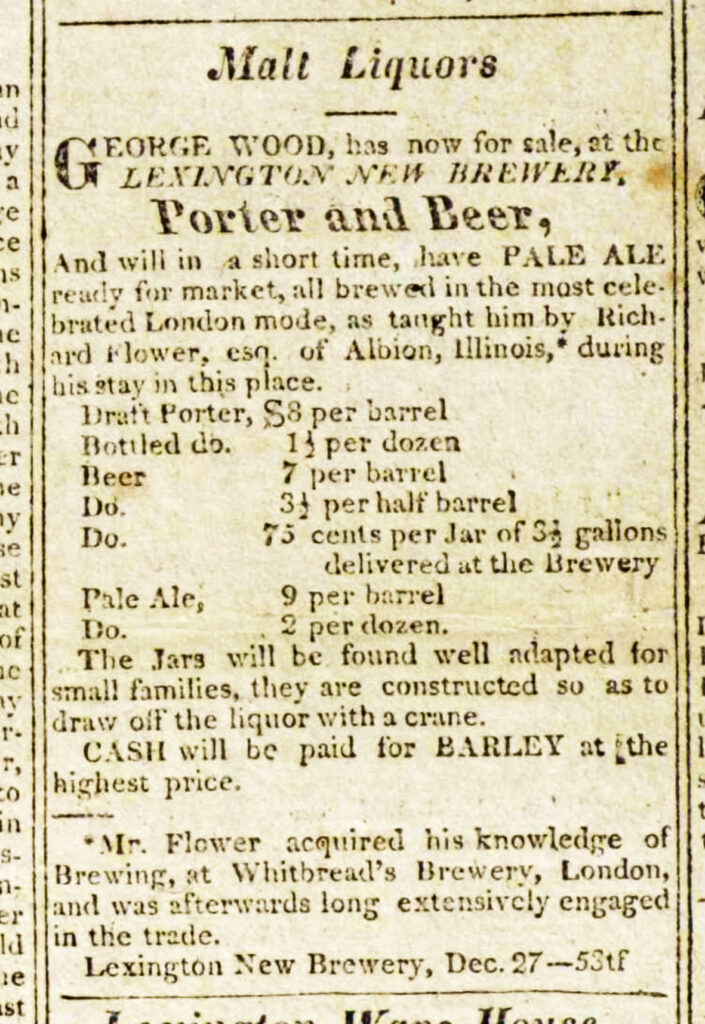

Richard’s son George had linked up with Morris Birkbeck, a Quaker agriculturalist and radical, and together they organised the purchase of 26,400 acres of land in the south of what was then called “the Illinois Territory,” and encouraged would-be settlers from England to come and join them. Among those persuaded was Richard, who was on his way from England to Albion with his wife and four of their children, including their youngest son Edward Fordham Flower, then aged 13. Richard and his party stayed in Lexington over the winter of 1818/9, where Richard apparently found time to instruct George Wood on London-style porter brewing.

Richard’s brother was the radical journalist Benjamin Flower (whose daughter Sarah, Richard’s niece, wrote the hymn “Nearer My God To Thee), and the English immigrants in Albion were vehemently anti-slavery, a stance which, obliquely, was to make Flower one of the most famous names in British brewing. Escaped slaves from Kentucky had settled in Albion, encouraged by the Flowers and others. However, the now-free negroes were always in danger of kidnappers looking to sell them back into slavery. Around 1823 one such gang, eight in number, grabbed a group of free black residents of Albion and made off with them. They were pursued by an armed party led by the 18-year-old Edward Fordham Flower, who captured the gang “at the rifle’s mouth,” freed their victims and led the kidnappers back to face the law.

This made the kidnappers’ associates determined to kill the young Flower: according to later newspaper reports a cousin was mistaken for him and left mortally wounded (this appears to be a young lad also called Richard Flower, who was killed when a gang of ruffians called at his family’s home in Albion, challenged him to a fight, and when he declined and turned away, threw an oxbone at his head, injuring him so badly that he died soon afterwards), and a bullet was fired through a window at his father’s house and smashed a mirror just above his head. The family decided that the safest plan was for Edward to leave the country. His father had a business commission in England, and Edward accompanied him in 1824, staying behind when Richard returned to Albion, and settling in Stratford upon Avon, Warwickshire.

After seven years working as a partner in a timber merchants, Edward had evidently raised enough capital built a brewery by the canal in Stratford in 1831, and began brewing strong ale, table ale and porter. About the same time one of Edward’s Flower’s cousins, Edward George Fordham, was turning the brewery at his farm, Ashwell Bury, in North Hertfordshire, into a commercial concern. It has been claimed that Flower was taught brewing by the Fordhams, though this seems to be based on the mistaken idea that the Fordhams began commercial brewing in Ashwell in the 18th century: there is no evidence that the Ashwell brewery was running before 1835.

The brewery apparently took some time to start to be successful, and in the meantime Edward, who clearly missed his life in America, and looks to have resented being forced back to England, “continually” planned his family’s departure from England, and seriously considered moving to Australia. When the Civil War came to America, Flower spoke at meetings around England in support of the North, and against slavery. Later, after he retired from the brewery in 1866, he returned to the US with his wife Celina for a six-month tour of the country he had left decades earlier. He also became a campaigner for a cause long since forgotten: against the use of “bearing reins”, restraints which made a horse hold its head unnaturally high, to the serious detriment of its health.

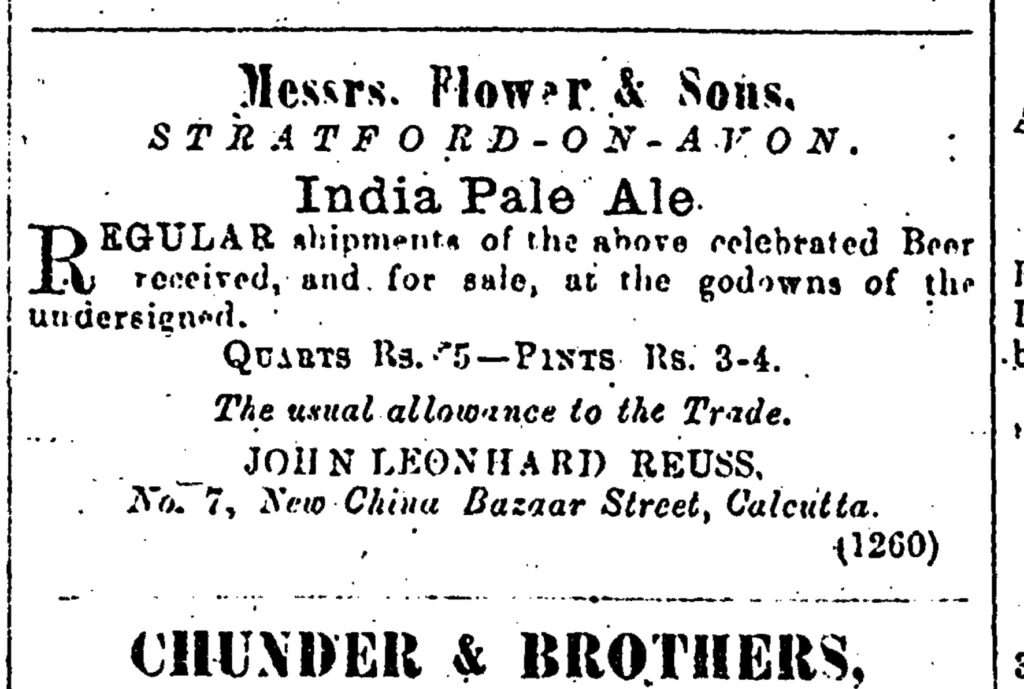

Flower’s brewing water was similar to that of Burton upon Trent, and it became famous for its India Pale Ale, which was being exported to India itself at least as early as 1868. By that time the company was turning over £100,000 a year, probably more than any other British brewery outside the main brewing centres.

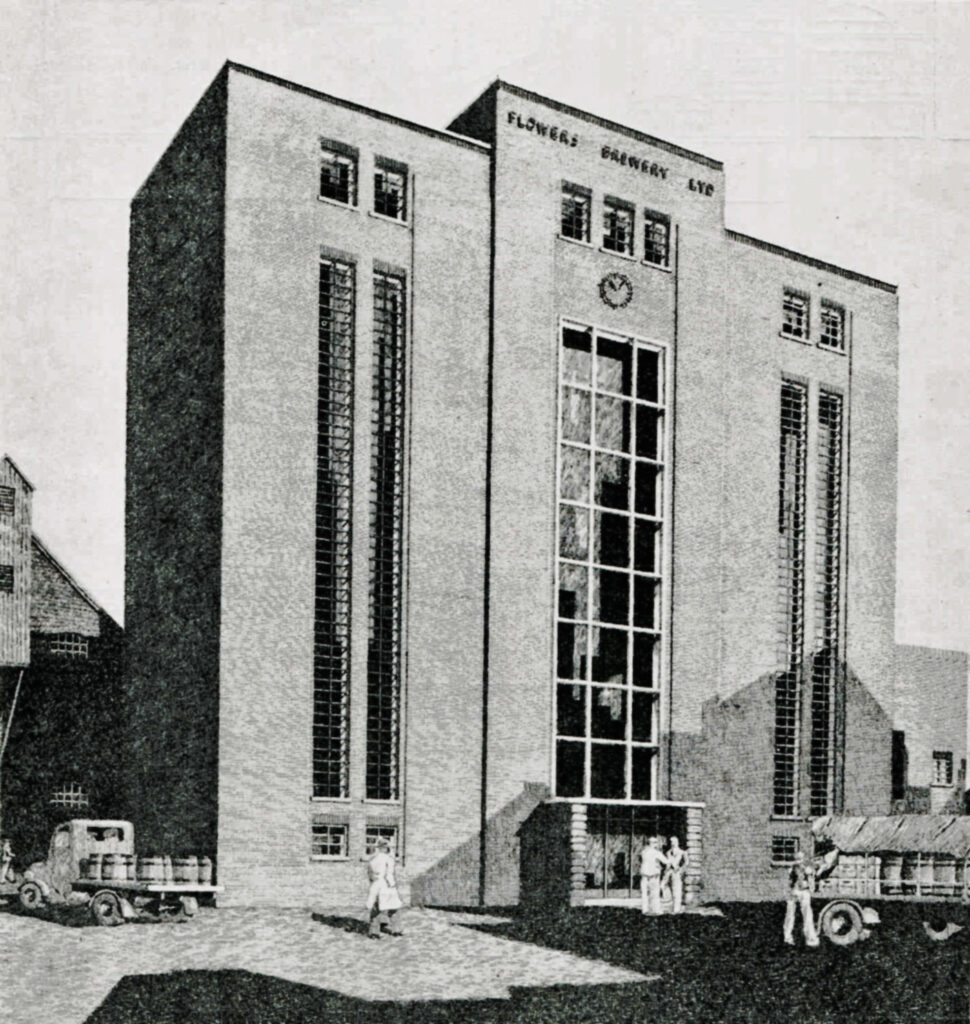

It was a well-known mid-sized regional brewer by the mid-1950s, but over-spending on a new brewhouse in 1951 left the company vulnerable, and it was snaffled in 1954 by the ambitious Luton-based brewer JW Green. (A couple of years earlier Green’s had taken over Fordham’s in Ashwell.) Green’s boss, Bernard Dixon, was looking for a better brand name for his company, and changed the name of Green’s to Flower’s Breweries Ltd. The next year, 1955, he used Flower’s name to launch Flower’s Keg, one of the first keg bitters in the country. (The beer inside was Flower’s Original bitter, supposedly “a very suitable beer for the kegging process”.)

Dixon eventually fell out with the Flower’s board, and he was replaced by one of Edward Fordham Flower’s descendants, Sir Fordham Flower. But the company was still struggling, and in 1962 it invited Richard Flower’s old employer, Whitbread, to take it over. Eventually both the Stratford and Luton breweries were closed, though in 1981 Whitbread revived the name of Flower’s Original, later bringing back Flower’s IPA as well. The Flower’s name survived the exit of Whitbread from brewing, and the last time I looked Flower’s Original was being brewed by Brain’s in Cardiff, though this was several years ago: if anyone has any news on if and where it is being brewed, do comment below.

“Chunder & Brothers”, below their advert in the Indian newspaper, is a great name, and also retrospectively descriptive of what might happen if you drank too much of their beer!

Yes, I deliberately leftpart of their ad in, knowing it would amuse …

Good article, Martyn.

Not knowing any better, but knowing enough that it had to be a pint of bitter, Flowers was my first legal pint back in the late 80s. Hadn’t realised that it was a Whitbread beer but that makes sense seeing as I was in Farnham at the time.

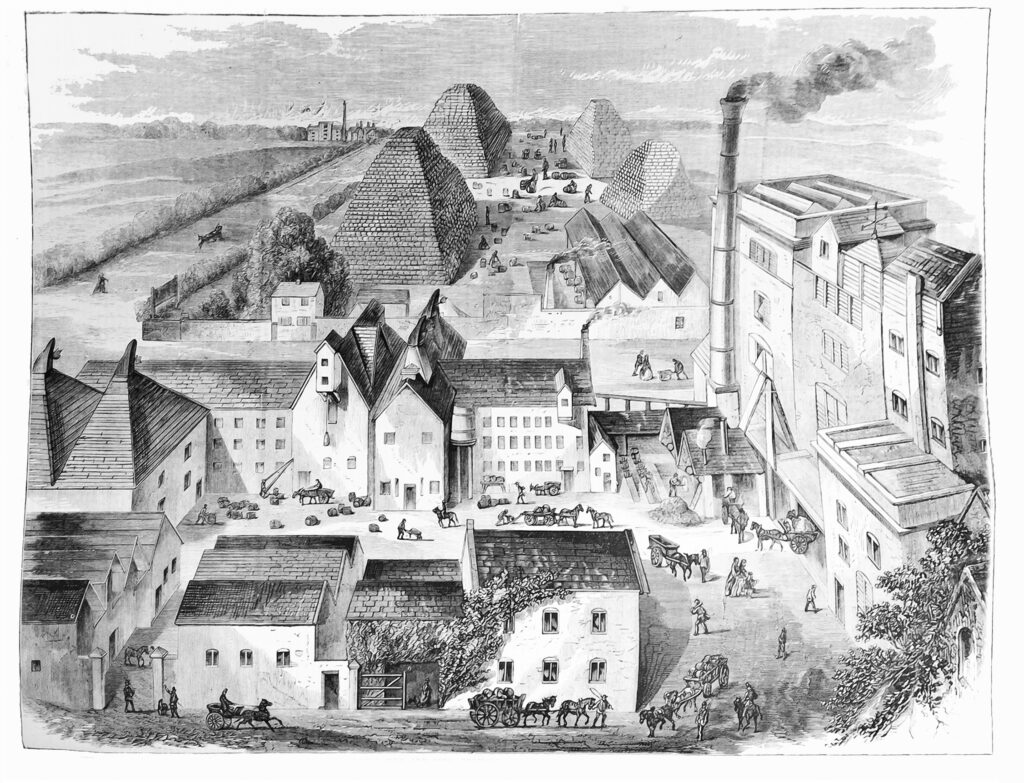

That’s a very fine brewhouse! Is it still standing?

I looked at the picture of Flower’s previous brewery for a couple of minutes – “what pyramids of casks?… oh”. Back then people who drank beer, really drank beer!

In Swedish a faucet is a Kran.

And in German it’s both a faucet and a crane. Sounds like a plausible name for some dispensing mechanism?

“Drawn off the liquor with a crane” sounds to me like a water bucket at the well. But that’s just a wild guess only so I could call it Pail Ale.

Drawing off by means of a crane means either that the jars have a tap, or there is some sort of siphon arrangement similar in principle to today’s spear dispense. The word “cran” is still used in Scotland by aged cellarmen for the latter.

It was of course Richard Flower’s old boss, Samuel Whitbread, who was instrumental in having Henry Dundas impeached, a key moment in the history of abolitionism.

A crane was a type of syphon or bent pipe for drawing liquor from a cask.