Kveik: a word we’re likely to be seeing a lot more of in the beer world. But what is kveik? Here are a couple of things it’s not:

Kveik is NOT a beer style. It’s the name given in parts of Western Norway to yeast used in the local tradition of farm brewing, it looks to be derived from an Old Norse word meaning “kindling”, as if the kveik kindled the fire in the brew, and it is apparently related to the English word “quick” in the sense of “alive”. In particular, kveik is NOT the Norwegian equivalent of Saison. Kveik is just one of half a dozen or so terms for “yeast” used in Norway, the others including barm (also found in Britain, of course), gjaer, gjest (from the same root as “yeast”) and gong, with kveik limited to the south-west of the country, but competing, even there, with the latter three words, which all had wider distribution.

Some similarities can be found in the brews made across the area where the term “kveik” is used: north of the Jostedal glacier they will generally be “raw” ales, that is, made without boiling the wort, and hop usage will be light to non-existent: generally restricted to leaving a bag of hops in the stream of wort running from the mash vessel. All will be made with water that has been boiled with branches of juniper in the pot, which gives a sharp, lemony/citric flavour to the ale, as well as helping to preserve against bacterial infection.

Kveik is NOT a particular strain of yeast, and saying “kveik yeast” is a bit tautological, although the term looks to cover a distinct family of yeasts. However, within that family are dozens, perhaps hundreds of different individual strains, and any one person’s kveik can contain between two and ten different individual strains. This use of multiple yeast strains appears to be important.

Some kveik are bottom-fermenting, some top-fermenting, and some intermediate, depending, basically, on where the brewer collected the yeast from at the end of fermentation. According to Lars Marius Garshol, who literally wrote the book on Norwegian farmhouse brewing, “in some areas, such as Sunnmøre and Nordfjord, there was a tradition that yeasts should be mixed every five years or so, and kveiks from those places show a much greater variety of yeast strains.”

Richard Preiss, co-founder of Escarpment Laboratories, based in Guelph, Ontario, whose company has done perhaps the most research into kveik of any on the planet, has suggested that these different strains need each other, that one makes a vitamin that the other ones need, and vice versa. According to Garshol, Preiss “always seems to get slower fermentations with single-strain yeasts from kveik cultures than [we see from others] with the mixed cultures. So they can survive without each other, but fermentation goes faster and easier with the help of the others. But doing an experiment to prove or disprove that in a way that’s reproducible by others is very difficult.”

That is not the most interesting fact about kveik, however. The aspect of kveik brewing that is most likely to ensure its adoption outside Norway is the range of flavours it is possible to get from the yeast, fruity and deep, which chime with the search for more flavour that seems to power much of the innovation in craft brewing right now. But there are other wonders: the high temperature tolerance exhibited by kveik strains, for example, many of which are happy fermenting at up to 40ºC.

Preiss, a tall, bearded and friendly Canadian, speaking at the Norsk Kornøl Festival in Hornindal, Western Norway, last month, revealed that his company had tested 25 different strains from samples of kveik supplied by Garshol, “and all of the ones we tested grew at 40ºC, while two thirds of them were tolerant to 42ºC, which isn’t normal in the larger world of beer: most people are fermenting at 20. This is remarkable. There are prominent yeast scientists that have engineered yeasts to work at 42ºC, and here’s a whole bunch of natural ones from Norway that do it too.

“This means that a home brewer who doesn’t have a lot of equipment, they don’t have a fridge to control the temperature, if it‘s 30ºC in a small city apartment they can still make a clean beer in the summer, and that‘s a little bit revolutionary, because that wasn’t really possible without these yeasts.” There are also, Preiss says, “some real opportunities for using these yeasts elsewhere, such as the ability to make good flavours, good beer at high temperatures. It means that a craft brewery in a tropical climate can maybe reduce their cooling costs and make their beer more energy-efficient.”

How did kveik yeasts evolve to be happy at such high temperatures? Garshol suggests it was due to the pressures the farm brewers were under, which influenced the yeasts they chose to preserve for brewing the next batch of ale: “The fermentation temperatures are crazy. But when you look at the old sources, they say ‘milk-warmÆ pretty much everywhere, in other words around 37ºC. Why is this? Obviously brewers want to add the yeast as quickly as they can. But as the wort cools, it cools more and more slowly. And with old-fashioned cooling methods and 150 litres of wort, that was slow. So there are lots of accounts of brewers having to stay awake until the middle of the night before they can add the yeast. And of course, the longer you wait, the greater the chance that some lactic acid bacteria gets in there. So you really want to ferment warm – the warmer you could ferment, the better.” Those yeasts that survived being thrown into wort at 40ºC to go on and ferment a successful, tasty beer would be the ones that get preserved for use in the future.

The same is true of kveik’s ability to dry out and still come back and thrive when rehydrated. Preiss says that when Escarpment received its initial samples of kveik, “the first thing we found out, and we found it out very quickly, is that this is not normal yeast. We got the dried sample in and rehydrated it, and the cells were looking healthy and plump within five minutes. We put some into some wort, went for lunch and came back 40 minutes later, and it was fermenting. That’s not normal for beer yeast. That was the first sign that this was probably something special.

“We did some fermentation trials of 25 kveik yeasts in comparison with standard Californian ale yeast, WLP001, the commonest yeast in homebrewing, and found they were pretty fast fermenters. Measuring the CO2 release rate 24 hours into the fermentation, some of the kveik yeasts had fermented twice as fast as the California ale yeast, and the majority, 19 out of 25, were outpacing it. This makes sense with what we saw with just rehydrating the yeast: it starts fermenting very fast. This seems to be a fairly common property with the kveik yeasts, and it is fairly unique, this rapid start to the fermentation. Brewers like that – brewers want to know that the fermentation is working. Some of the strains we tested were pretty much finished fermenting within two or three days.”

Again, the explanation for this comes from the pressures the yeast was put under. Norwegian farmhouse brewers did not, and do not, brew regularly: perhaps only two to four times a year. They needed to preserve their yeasts between brewings, and before refrigeration the only way to do this was by drying. Those yeast strains that survived drying were thus selected for. Similarly a farm brewer might have very little notice that a new supply of ale was needed: the arrival of unexpected guests, for example. Once more, those yeasts that started up quickly, and finished speedily would be optimally selected for.

Rather harder to explain is the alcohol tolerance of kveik strains. According to Preiss, “in terms of alcohol production from the wort, some were pretty efficient, but there was a big range of attenuation, from 66 per cent to 95 per cent, and in alcohol production, from 4.4 per cent to 6.4 per cent.” However, when Escarpment tested for how much alcohol kveik strains could cope with, “we were pretty stunned. We tested eight kveik yeasts for ethanol tolerance, and they were all growing in up to 12 per cent alcohol, which is not normal: conventional ale yeasts exhibit a spectrum, some that are not very good at surviving in high alcohol and some that do survive. It’s very rare to screen eight strains and find all of them growing like that. We found that even if we went up to 16 per cent alcohol, a third of the kveik strains will still grow, which is pretty remarkable.

“We also looked at the flocculation and we found that two thirds were very flocculent, many very, very flocculent. But even in one kveik sample there might be a huge variability in the flocculence between the different yeasts in the strain. Some are not very flocculent at all, some are dropping crystal clear in ten minutes. It’s again interesting to see that kind of variability in a single yeast community.

“We also tested the flavours they produce, using gas chromatography. We picked up a few pretty consistently with the kveik strains, fatty acid esters such as ethyl caproate, giving pineapple flavours, ethyl caprylate, giving pineapple, waxy and cognac flavours, ethyl decanoate, which is red apple, phenethyl acetate, which is floral and honey. Only two of the strains were phenolic, meaning [the rest] were likely picked at some point by humans because they were not phenol-producing, making for a taste that is very typical of ale yeasts, clean but with some fruitiness as well. The isobutenol, or fusel, levels were only around 50 per cent of US-05 [a common American homebrew yeast]. We also tasted citrus in a lot of the kveiks, we tasted rum and caramel flavours and we tasted almost mushroomy flavours as well. We’re still not sure what all those favour compounds are, and we may very well find that there are some unique ones made by kveik that are not made by other yeasts.”

Another thing Escarpment noticed, Preiss says, is that there seems to be two main groups of kveiks, looking at their genomes, which correspond, for the most part to the geography of the region where kveik is found: one group, including Hornindal, to the north of the Jostedal glacier, the largest glacier in Europe, and the Sognefjord, Norway’s largest and deepest fjord, and the other group, including Voss, to the south of those two important geographical barriers. “It suggests that though they may have had a common ancestor, they evolved separately because of the geographic isolation of the regions they are now mostly found. The glaciers and the fjords in Norway create barriers which made it hard for people to move around in the past. We don’t often see these kind of geographic links in the genetics of yeast cultures.” Garshol points out that the divide also matches a split between brewing processes: to the north, almost entirely raw ales, with the wort unboiled; to the south, most brewers boiling their wort. (For a proper discussion see Garshol’s own blog here)

The unanswered question at the moment is where kveik strains fit on the yeast family tree. A study released in 2016 by the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology and the University of Leuven in Belgium found that all commercial beer yeasts come in two strains, Beer One, which dates from the late 1500s or early 1600s and Beer Two, dating from the 1650s or so. So far Preiss and his team at Escarpment have only been able to make a rough fingerprint of the kveik strains they have, “which is not very high-resolution, but it’s typically accurate and it can give us an indication of the genetic relatedness of different yeasts. So what we found when we took this approach is that the kveik yeast across different samples were more closely related to each other than they were to the other strains of domesticated ale yeasts.

“Because of that, we think that the kveik may form a separate branch on the family tree of beer yeasts. That being said, if we go and look for the most closely related yeasts, it’s a group of strains that includes some Kölsch yeasts and English yeasts, as well as a Lithuanian strain we looked at. So it’s possible that all these yeasts have a common ancestor at some point in history. But we can’t say that confidently yet, without whole-genome sequencing.”

Finding out more with whole-genome sequencing is expensive – $1,000 or $2,000 per strain. “But we think that because of the way the kveik have been maintained, and maintained for much longer, they haven’t been stuck in a lab for 100 years, this may be a new way for us to study yeast domestication without necessarily studying the commercial yeasts,” Preiss says. “We applied for a grant, and I’m happy to say that we did get funding to do the whole-genome sequencing for these kveik strains. We can hopefully have an answer some time in the spring, and hopefully say for sure that the kveik are a separate line on the family tree and have a little bit of a better idea of exactly where and when they broke off from the other beer yeasts. We’re using these Norwegian yeasts to really push brewing science, and yeast science, forward.”

Another question to be answered is: are there other yeasts like these? “Yes, of course, in Lithuania, and Russia and probably in other places,” Preiss says. “That’s a really exciting opportunity, to maybe look at these and start to understand these other yeasts that aren’t industrial and aren’t wild. The term I’ve started to use is ‘landrace yeasts’, which I think works well for an organism that’s been domesticated traditionally, without the involvement of industry, and because of that unique cultural framework, it has become genetically distinct from the other populations of that species. It suggests a third entire category of yeasts that have not really been explored in brewing.”

I was lucky enough to get to see a “Norwegian farm brewer” in action: Stig Seljeset, whose father was a farmer brewer, and who wanted to maintain the tradition. Stig brews at Borghild Tunet in Hornindal, “tunet” being the Norwegian for “farmstead”, home of Idar Nygård, deputy mayor of Hornindal, who has preserved the old farmstead much as it would have looked a century and more ago. The beer Stig brews is a “raw ale”, made without boiling the wort. The first step is to boil up water (which comes from a borehole up in the mountains, and contains lots of dissolved limestone/chalk) and branches of juniper in a large iron pot, perhaps 100 litres or so, suspended over the fire in the old farmstead kitchen (exactly the same way that Frank Clark does in his reproduction 18th century farmhouse kitchen in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia). All the equipment is then scrubbed down and washed out with the hot juniper-water, before Stig uses milk churns to carry hot juniper-water to the “mash tun”, a blue 200-litre food-grade plastic tub set up in the garage across the farmstead yard.

The malt – on this occasion Munton’s pale lager malt from Suffolk, though Stig is happy to use whatever malt he can get hold of – is added, and mashing takes place at 68-70ºC. Once sufficient time has passed for conversion of starches to sugar, the grain is transferred by buckets into the “lauter tun” – another blue plastic tub, this one with a tap set in the bottom. Beforehand, Stig has set a wooden “filter” in the tun, above the tap hole, augmenting this with leafy twigs of juniper. The wort left in the “mash ” is then poured into the “lauter tun”, and allowed to strain through into milk churns, while more hot juniper-water is poured in to “sparge” the malt. A bag containing loose hops – Challenger this time, though again Stig isn’t fussy, and will use what he can get – is hung in the churn and the hot wort runs over the hops, like a teabag. This is the only contact Stig’s ale has with hops.

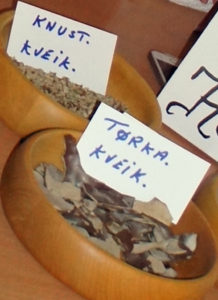

Wort cooling takes place by looping a circular length of hosepipe with holes in round the top of the milkchurn and running cold water from the tap through the hosepipe, which trickles down the outside of the churn. Once cooled sufficiently, the wort is carried down to the cellar of the old farmhouse, where it is added to the “fermenting vessel” – one more blue plastic tub. Stig aims for a temperature of 32ºC when he pitches the kveik into the fermenting vessel, but it was a cold day, and his thermometer (the only “technology” Stig uses) showed the wort had dropped to 28ºC, so the last 10 litres of wort were added uncooled to bring everything up. The kveik, a mixture of dried yeast from brewings in 2012 and 2016, is warmed up and brought back to life in a wooden bowl of wort by the kitchen fire, and then added to the fermentation tub and left in the dark cellar to work magic. The final result, in a few days, will be cloudy, slightly lemony and sharp, probably around five per cent alcohol by volume, and delicious.

“all of the ones we tested grew at 40ºC, while two thirds of them were tolerant to 42ºC, which isn’t normal in the larger world of beer: most people are fermenting at 20. ”

Growing and fermenting are very different things – many yeast grow optimally at 30ºC, the point of fermenting at 20ºC is to minimise off-flavours even though the yeast are not at the optimum growth temperature. What makes these beasties interesting is the prospect of clean fermentations at 30ºC or more, which would be terrific for “low-tech” homebrewers without temperature control of fermentation, particularly if they were available in dry form rather than (more expensive, shorter shelf-life) liquid form.

In fact the most challenging thing is not clean fermentation at high temperatures, it’s getting clean fermentation at fluctuating temperatures – you may get more off-flavours varying between say 17-23ºC than at a steady 25ºC. If the Norwegian yeasts can do that, then that becomes very interesting to the low-tech homebrewer.

Actually, fermenting with normal commercial yeast at above 25C is a considerable challenge. In the same tests, WLP 002 wasn’t able to ferment above 30C at all, for example. And labs that have tested kveik next to commercial yeasts found that the commercial yeasts that were able to ferment at 35C produced so much fusel alcohols that “it was perfect if you wanted an instant headache.”

The kveiks nearly always have varying temperature during fermentation, because there is no temperature control beyond maybe wrapping the fermenter with some insulation. And the brewers have 150-liter batches. So from pitch temperature the temperature will drop a bit, then rise again when the yeast really gets going, then drop again.

Lab tests indicate that these yeasts make much the same aromas at 25C, 30C and 35C. Probably 40C, too, but the labs didn’t have equipment to check that.

I am not aware about when these beers are brewed, so it is a little confusing to me to read that the fermentations are at more than 25 C, but as per the pictures, the cloths of most of the brewers seems to be a winter season. Could you clarify it? Thanks!

The figures refer to the temperature of the wort, not the ambient temperature The pictures were taken in October, and the ambient temperature was about 9ºC.

We use some insulation on the fermenter, and the active fermentation (2 days) also produce heat. When I do the Christmas Ale, it can be minus 15° C, and still ferment in the Brewhouse outside… (With extra sheepfurs outside the fermenter)

>Some kveik are bottom-fermenting, some top-fermenting, and some intermediate, depending, basically, on where the brewer collected the yeast from at the end of fermentation.

Can you explain what is meant by this? It is my understanding that these terms were historical, and don’t really mean anything, but the way you say it makes it sound like it’s a thing. I’ve never understood Ale vs lager beyond the flavors and temperatures.

Yeasts generally fall into two kinds, those that settle after fermentation at the top of the fermenting vessel, and those that settle at the bottom. Generally (but not always) warm-fermentation yeasts settle at the top, cold-fermentation yeasts at the bottom. Thus “top-fermenting” and “bottom-fermenting” have become synonyms for “ale yeast” and “lager yeast” respectively. In fact, of course, the actual fermentation is taking place in the middle …

My main interest in the traditional brewing process was making the malt and the saccharification until I heard about kveik. I can’t comment about the technical details but I can say that I learned a lot from reading this and the comments above.

Just wondering if the hops are locally grown?

That would depend on the brewer. Most of those who actually use hops use whatever they can get hold of, I believe.

Absolutely, ‘kveik is NOT the Norwegian equivalent of Saison’. I’ve used kveik yeast several times now (one or two batches a year). Only because I live in Norway, though. I don’t rate it much myself. The ‘lucky’ folk who drink it prefer my other beers too, including Saisons and English ales, which are fermented with yeast strains which have been selected for (over years) by professional Brewers and their brewery environments. Kveik has been promoted around the internet for 2-3 years now, but there is a distinct lack of positive feedback. I’d recommend Kveik to a Brewer who insisted on mashing a ‘romantic’ Norwegian farmhouse ale. Otherwise avoid it. It’s bland, even at higher fermentation temperatures. Very plain, 1-dimensional ‘orange’. It lacks a pleasant ester profile one would normally expect from a well-selected Brewer’s yeast strain. I suspect Kveik began as Baker’s yeast and didn’t evolve as much as a typical Brewer’s strain, due to no standardised practices. The periodic drying of Kveik probably had a detracting impact on any character that might have been selected. (Not unlike today’s commercially available dried yeast offerings.)

Hmmm – my experience with drinking kveik-brewed beers and other Norwegian farmhouse ales is that they are pretty uniformly excellent, with masses of fascinating flavour. I suspect yours may be a minority opinion.

I’m sure it’s a ‘minority opinion’ in the fantasy world of the blogosphere, Martyn. A real world tasting suggests otherwise. Not restricted to my taste either.

I saw 600+ people thoroughly enjoying the beers at the kornøl festival in Hornindal. Many hundreds – possibly thousands – of people still brew these beers in Norway. If you and your pals don’t like them, that’s fine – more for those of us that do. And don’t talk about “the fantasy world of the blogosphere” on my blog – I’m allowing you a platform to disagree with me, I don’t expect to be insulted for doing so.

You really hate everything about Norway,dont you.Why dont you do us all a favor and simply move back to your British Isles.

John, if you don’t like the taste of it then nobody can really argue with that, since taste is a subjective thing. Meanwhile three expert judges, tasting blind, picked a beer with kveik as one of the top 10 beers on the market in Norway, out of 269 . And a beer brewed with kveik came out as #1 in the American home brewing championship this year, out of 8618 beers. I’ve spoken to more than one brewer who intends to start commercial brewing using only kveik yeast. And so on.

It would be extremely surprising if kveik was originally a baker’s yeast, for two reasons.

First, because historically there was no such thing as baker’s yeast, unless you count sourdough. Baking uses up the yeast, so you need a source of yeast, and historically the source was brewing. Norwegian farmers would use their brewing yeast when they wanted to bake something.

Secondly, because historically Norwegian farmers did almost no leavened baking at all. Until about 1950 hardly any wheat at all was grown in Norway, and you couldn’t make leavened bread from barley and oats, which is what the farmers grew. So leavened bread was a very rare treat, available only for Christmas, if at all.

Given this it would be astonishing if kveik really started life as a baking strain in any real sense of the word.

I’ve used strains a lot worse than some Kveik, Lars, but I have English and Belgian strains that work much better for me. Some of the ales I’ve fermented with ‘Voss’ and ‘Muri’ have been good. Just not as good as the ales fermented with my other strains. The latest competition result is great, but why does it contrast so much with earlier performances in Norwegian home brew competitions? Norway has lagged behind, historically, but I’m sure many things not produced locally were being imported in the past, at least to some degree? Historically, Norway was a great shipping nation. I’d be surprised if baker’s yeast wasn’t being used for baking until the 1950s. Contrary to popular belief, although the yeast are used up, bakers too maintain yeast cultures and even reserved a little dough for the next batch.

You should be aware that Muri is not kveik. That’s almost certainly a wild yeast that was grown by accident instead of the real kveik. So I can certainly understand if you’re not impressed by Muri.

“The latest competition result is great, but why does it contrast so much with earlier performances in Norwegian home brew competitions?”

What do you mean? This was an American home brewer using a Norwegian yeast in the American National Home Brewing Championship. Norwegians don’t participate in that competition.

“I’m sure many things not produced locally were being imported in the past, at least to some degree?”

Absolutely, but the farmers generally would not buy anything they didn’t have to buy. They were poor and lived largely outside the money economy.

“I’d be surprised if baker’s yeast wasn’t being used for baking until the 1950s. ”

In the cities I’m sure it was used, but as I’m saying in the countryside generally there was no leavened bread. Possibly one small loaf for Christmas, but no more. The farmers ate crisp bread, which is not leavened.

“Contrary to popular belief, although the yeast are used up, bakers too maintain yeast cultures and even reserved a little dough for the next batch.”

That’s sourdough.

‘That’s sourdough’? Yes, it can be. I maintain a fresh culture from Idun dry yeast, for baking bread. It gets better over time and reduces proving time ; )

Past entries of Kveik brews in Norwegian homebrew competitions didn’t do so well. Are the Americans getting all romantic about Norwegian yeast? Or did someone dump half of Yakima Valley’s stock into a brew? My Idun culture would have made that sing ; )

Lars, from Truls’ (2016) dissertation, “assessors were asked to rate the beer they determined to be different from the reference to either be equal, better or worse. Idun, Muri and Hornindal were rated better then WLP001. Sigmund and Stranda were rated to taste worse.” It was clear too from the fermentation data (ibid.) that Idun (Baker’s yeast) can ferment wort and that Kveik strains actually ferment better at lower temperatures, in terms of attenuation. The lower attenuations at higher fermentation temperatures implies the yeast cells are under more stress therefore not necessarily being fermented under optimal conditions.

Hardly a ‘platform to disagree’ then, Martyn. An acquired taste is a requirement in Norway, especially with traditional offerings. That’s not a minority opinion either. What I’d actually like to see is some convincing evidence to back up the wild speculations surrounding Kveik. What’s next? ‘English ale yeasts are descended from Kveik’? Highly unlikely, all things historical considered. What little genetic data exists for Kveik wouldn’t have past QC in my lab. Any future genomics study needs to include more than Kveik. Norwegian Baker’s yeast too. However, it won’t affect my taste and opinion of Kveik ale.

Wow, really interesting. One of the best things about craft beer is the attention to detail drinkers and brewers pay to even the most subtle of features! This really shows how craft beer can breed interest and passion about other cultures and their traditions as well!

[…] siis myös brittioluen guru Martyn Cornell, joka bloggaa Zythophile-nimimerkillä, on käynyt Norjassa maalaisoluiden syntysijoilla. Hän ennustaa, että kveikistä tullaan kuulemaan vielä paljon […]

[…] Flere norske ølbloggere har igennem et par år dykket ned i norsk ølhistorie og øltraditioner i forskellige regioner i Norge. En af de ting der kendetegner norsk øl er “Kveik”, et ord der findes mange misforståelser om, så Lars Garhol sætter på plads: “Kveik”, what does it mean. Martyn Cornell griber bolden og fortsætter med How to brew beer like a Norwegian farmer. […]

[…] Uns Baiern fehlt ja leider eine ungebrochene alte Hausbrautradition. In Norwegen ist sie noch lebendig. Hier ist eine sehr detaillierte Beschreibung, wie einer der norwegischen Brauer da vorgeht: https://zythophile.co.uk/2017/11/20/how-to-brew-beer-like-a-norwegian-farmer/ […]

Jolly interesting about kveik. An extremely minor point re the caption on the photo of the lovely old turf-roofed kitchen at Borghild Tunet, the normal Norwegian word for stallion is ‘hingst’. Stalljen would be a Norwegian translation of the English that I’ve never heard used in connection with horses (nor anything else, not that I know everything).

Dunno, mate: I’m only repeating what I was told …

“Stalljen” would be a dialect form of “stallen”, which translates to “the stable” (as in where the horses sleep. Thank you for an interesting article!

[…] блога Zythophile Мартин Корнелл рассказывает о фермерском пивоварении в Норвегии и о том, как варят […]

What I find frustrating is that I cannot find any place that sells a multi strain Kviek yeast pitch. Everyone seems to be selling isolates. DO you know where you can buy a multi strain pitch from?

Have you tried Escarpment Yeast in Canada?

[…] Norwegian yeast came to be. However, it’s been around for a very long time. There’s evidence of the use of kveik in a Norwegian farmhouse brew dating back to the early 1600s. More so, there […]

[…] https://zythophile.co.uk/2017/11/20/how-to-brew-beer-like-a-norwegian-farmer/ […]

[…] How to brew beer like a Norwegian farmer […]