Brewers’ advertisements in Victorian newspapers are almost always strictly utilitarian: a list of up to around a dozen beers in three main styles, mild/old ale, pale/ale bitter and porter/stout, each style shown available in three or four strengths, and with their prices listed per gallon/firkin/kilderkin. That’s it. If you’re lucky you might get a reproduction of a medal won at an international exhibition, or, very occasionally, a line drawing of a stoneware jar or a bottle label. Newspaper printing technology wasn’t up to reproducing illustrations cheaply and well. So this ad from the Western Mail in Cardiff in June 1888 by the Hereford brewer Watkins and Son would be a rare and lovely find even without being a feast of unwitting social commentary and unintentional comedy. I love it. I want it on a T-shirt. I want it tattoed on my back. (Alright, maybe not that last one.)

Brewers’ advertisements in Victorian newspapers are almost always strictly utilitarian: a list of up to around a dozen beers in three main styles, mild/old ale, pale/ale bitter and porter/stout, each style shown available in three or four strengths, and with their prices listed per gallon/firkin/kilderkin. That’s it. If you’re lucky you might get a reproduction of a medal won at an international exhibition, or, very occasionally, a line drawing of a stoneware jar or a bottle label. Newspaper printing technology wasn’t up to reproducing illustrations cheaply and well. So this ad from the Western Mail in Cardiff in June 1888 by the Hereford brewer Watkins and Son would be a rare and lovely find even without being a feast of unwitting social commentary and unintentional comedy. I love it. I want it on a T-shirt. I want it tattoed on my back. (Alright, maybe not that last one.)

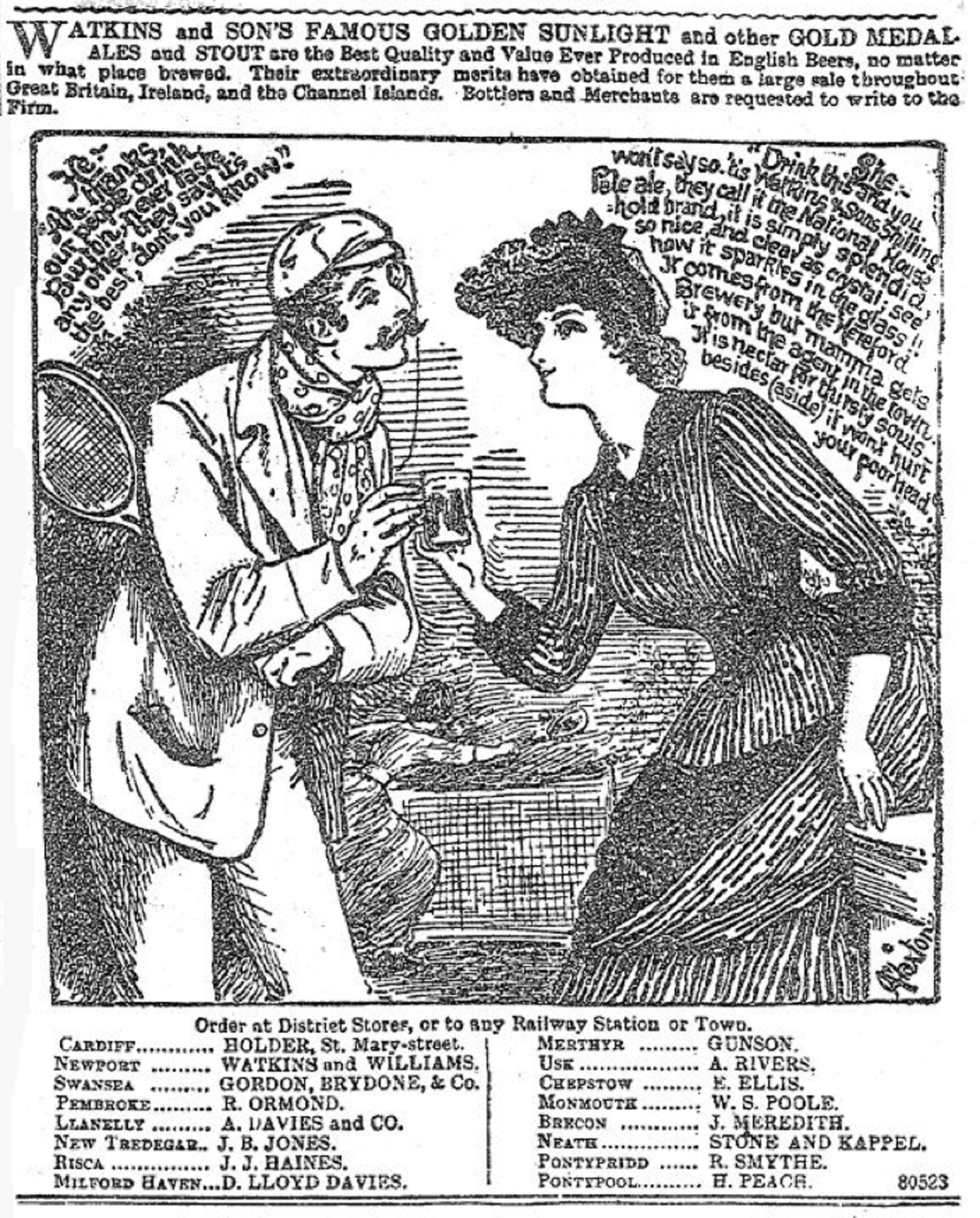

This is clearly meant to be an upper-class or upper-middle class setting. The fashionable game of lawn tennis, which had only been developed in the previous decade in Warwickshire, a short distance from Hereford, is being played (note the young woman leaping about in the background). The languid-looking moustachio’ed young chap with the fashionable monocle, cap and blazer accepting a glass of pale ale is talking in upper-class English: he is drawling “Ah, thanks”, referring to “our people”, meaning his family, and saying “don’t you know”. This is an expression parodied in the 1880s as an upper-class affectation, and still, by Paul Merton, parodied 120 years later don’cha know?

The square-jawed and forthright young woman offering the beer is wearing a bustle and has the exaggeratedly narrow waist also fashionable in late Victorian times: she appears underimpressed by the slightly foppish young male tennis player: she is mocking his insistence that only Burton-brewed beers are worth drinking, she hints that, at a shilling a gallon (suggesting an OG of 1045 or so, 4.5 per cent alcohol by volume) it represents better value than Burton beers (which would have cost half as much again, at least) and, in an aside, suggests, I fear, that the fellow may be a neurasthenic hypochondriac, as well as too keen to condemn a beer before he has drunk it.

The clumping dialogue is particularly compelling, like a rivetingly bad radio ad on Yokel FM:

He: “Ah, thanks, our people drink Burton, never taste any other, they say it’s the best, don’t you know.”

She: “Drink this and you won’t say so. ’Tis Watkins & Son’s Shilling Pale ale, they call it the National Household brand, it is simply splendid, so nice, and clear as crystal: see how it sparkles in the glass!! It comes from the Hereford Brewery but mamma gets it from the agent in the town. It is nectar for thirsty souls – besides (aside) it won’t hurt your poor head.”

Mamma, in real life, wouldn’t have had any idea where the household ale came from, of course: the cook would get it in, and probably pocketed a little thank-you from the agent in the town every Christmas to go with the regular brown envelopes from the butcher and the grocer.

Watkins was run by a former Hereford publican called Charles Watkins, and the brewery’s best-known beer was its Golden Sunlight Ale.

Another illustrated ad in the Western Mail from a few years later, February 1891, shows a different square-jawed young gel shielding her eyes from the brilliance of the beer:

“Keep the Golden Sunlight in your house, it is a light pale golden ale of pleasant flavour and wonderful value, it is good, it is light, it is pure, you will like it better than the stronger Burton Ale and it will not disagree with you.”

It’s light – did we mention that? And better than that Burton muck, again. And good value. Did we talk about it being light? Hence the name – sunlight, geddit? At 10 shillings and sixpence for nine gallons, one shilling and tuppence a gallon, Golden Sunlight looks to have been around 1050 or 1055 OG, five to 5.5 per cent abv, while Burton IPA was rather darker (“our beer is LIGHT!”) and around six or seven per cent abv. The comment from the City Analyst of Glasgow that it “resembles in composition the Läger Beer [sic – is this the earliest example of the heavy metal umlaut?] of Germany” is a reminder that British brewers were becoming worried about competition from the lighter, in all senses, beers of the Continent. Golden Sunlight, ” a light pale golden ale”, is also a reminder that British brewers made ales that were other than “boring brown*” a century and more before Summer Lightning and its many imitators.

Watkins and Son is probably most famous, mind, for one of the younger sons, Alfred, a former travelling salesman for the brewery, a pioneering photographer, and the man who came up with the concept of “ley lines”, the idea that prehistoric man had built landmarks across the countryside that linked up into a series of perfectly straight trackways. Unfortunately for Alfred, the lines he saw in the landscape were an artifact of the large number of random points he was looking at. Never mind, Alf – the fruitcakes love you.

The brewery was sold by the Watkins family in 1898 to the Tredegar Brewery of South Wales, which eventually moved all its brewing operations to Hereford. In 1945 it was acquired by the Cheltenham Original Brewery, and brewing only ceased at Hereford in 1963.

Now for the regulation advert again: it’s just over a week before the official publication in Britain of my book Amber Gold and Black, the British beer styles bible, the best book ever on the history and development of everything from bitter to porter, mild to IPA, and two months before it comes out in the US, but you can get it now here from Amazon UK, or you can order it through my mate Paul Travis at BeerInnPrint or if you’re in the US or Canada you can order it here from Amazon.com in the US, who will deliver it when it arrives from Blighty. Good reading!

*I need to say, incidentally, that I reject utterly the idea of “boring brown”

Good stuff. But what have you got against “boring brown”?

Nothing whatsoever, absolutely the opposite – see my note at the foot of this piece. I LOVE ‘boring brown;.

that golden sunlight one is lovely.

Sorry, what I meant was why do you reject the idea of “boring brown”? You say you love it-what exactly do you love about something that is boring and brown?

What I’m rejecting is the idea that brown beer equals boring, and what I’m loving is a great many beers categorised by some as “boring brown”. Sorry for not phrasing it as well as I should have …

I see that brewers were not above using lissome young ladies in the 1880’s. Sort of like today.

Ah, I agree brown doesn’t always equate to boring. However, it hasn’t gained such an association for no reason, either. Unfortunately, there are plenty of beers that ARE brown and boring. Now there are some dull golden ales, but it seems often brown is the defaul. My local micro produces some of the dullest brown beers possible so there is definitely some truth in the stereotype.

[…] Victorian Britain’s finest beer ad « Zythophile […]