Time to give another popular pub name myth a thrashing. There are more than 150 pubs around Britain called the Chequers, which puts it into the top 30 pub names, and yet the explanation given in most pub name books for the origin of the sign is complete cobblers.

The likeliest source of the problem seems to be Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, which declares that “the arms of FitzWarren [that is, blue and gold checks], the head of which had the privilege of licensing ale-houses in the reign of Edward IV, probably helped to popularise this sign.”

Almost every writer has repeated this story without making any checks (pun intended). Brewer’s itself looks to have nicked the claim from the Gentleman’s Magazine, which printed the story of the FitzWarrens, their chequered arms, and alehouse licensing as the origin of the pub sign in September 1794. However, every claim in the tale is nonsense. For a start the Warenne (not FitzWarren) family, Earls of Surrey, whose arms were indeed “chequy azure and or”, died out in the direct line in 1347, during the reign of Edward III, more than a century before Edward IV.

The right to their chequered arms passed down through their relatives the FitzAlan family and on to the Howards, Dukes of Norfolk, who still quarter the Warenne arms with those of Howard and FitzAlan and their ancestor Edward I’s son Thomas. John Howard, the first of the family to be Duke of Norfolk, was treasurer of the royal household under Edward IV. But there is no evidence that he, or anybody else, had “the privilege of licensing alehouses”: Edward VI was king when the first Act bringing in licences for alehouses was introduced, in 1552, and granting licences was a right given to local magistrates.

In fact, although the alleged “Fitzwarren” connection to the Chequers innsign has been republished as recently as the Wordsworth Dictionary of Pub Names, printed in 2006, it was trashed as far back as 1875, by Mark Antony Lower, author of a book called English Surnames, which includes a chapter on pub names. Lower calls the idea that the pub sign represents the arms of the Earls of Warenne/Earls of Surrey “foolish”, and says, politely, that any charter giving the Warennes the right to issue alehouse licences “would be very difficult, I think, to produce” – meaning that it never blahdy existed.

Lower also points out that the chequers seen on alehouse signs were generally red and white, not the Warennes’ blue and gold, and he links the red-and-white chequers to the “red lattice” that seems to have been a popular painted indicator that the premises on which they appeared was an alehouse. William Shakespeare mentions a red lattice window on an alehouse in Henry IV, and Thomas Decker wrote in 1632 in English Villanies that “A whole street is in some places but a continuous ale-house, not a shop to be seen between red-lattice and red-lattice.”

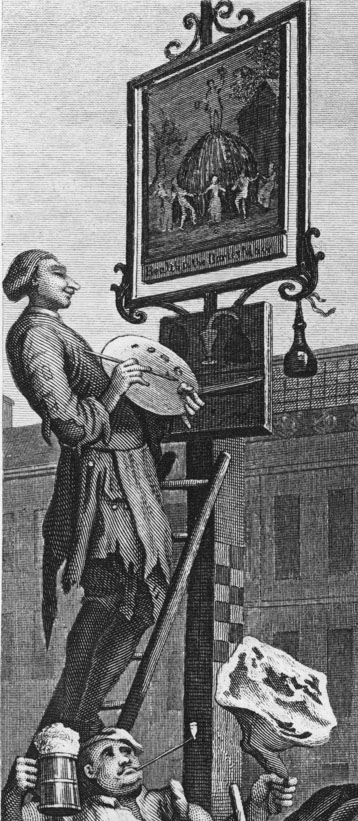

The transformation of the red lattice to painted chequers seems to have taken place between Decker’s time and that of William Hogarth in the mid-18th century, whose engraving of Beer Street shows checked squares painted on the signpost of the Barley Mow pub in the foreground, and on the wall of the Sun pub in the background. It looks as if, at a time when many other buildings on unnumbered city streets would have borne signs, the specifier of a pub or alehouse was now painted chequers. (Perhaps, as some have suggested, the chequers meant “boardgames played within”, or “money exchanged here”, but I can’t see the former being a big enough deal to advertise or the latter being so common that both Hogarth’s Beer Street pubs would engage in it.)

By the 19th century, if not before, the chequers that showed a place sold alcoholic liquor were being painted on the doorposts of pubs: both Charles Dickens and William Thackeray refer to it. Thackeray described in one of his lesser known novels, Men’s Wives Mr Eglantine arriving at the Bootjack Hotel, Berkeley Square, an inn owned by Mr Crump, saying: “Eglantine leaned against the chequers painted on the door-side under the name of Crump, and looked at the red illumined curtain of the bar.” Dickens, in David Copperfield mentions briefly the “chequered sign on doorpost” of a public house where a glass of water for Dora was obtained. For Lower in 1875 the “chequered square painted upon the doorpost” was still “common to many inns bearing a more specific [sign].”

It is quite possible that some, at least, Chequers pub signs are derived from the Warenne arms, most likely from their appearance as one of the quarterings in the Howard arms: the Howards were big enough landowners to be honoured multiple times in such a way. (A slap, incidentally, for Dunkling and Wright’s A Dictionary of Pub Names for saying that “In the village of Lytchett Matravers, Dors[et], the sign relates to the chequered battle-flag of the Duke of Arundel.” No such person – Dunkling and Wright confuse the Duke of Norfolk with the title traditionally given to that duke’s oldest son, the Earl of Arundel.)

Some Chequers pub signs may come from other armigerous families besides the Warennes/FitzAlans/Howards who bore chequered shields, such as the Fiskes of Laxfield in Suffolk and the Moltons of Pinho in Devon. A few may come from the game of chequers, or draughts, some from the name of the chequer tree or wild service tree, which certainly grows in or near several Chequers pubs in Kent and Sussex. I’m not convinced that the sign has anything to do with moneychangers, another popular claim in pub name books: I know of no evidence that inns ever acted as moneychanging operations. My bet is that many Chequers pubs were originally unnamed alehouses that had a chequered pattern painted by the door to show strong drink was sold inside, and which subsequently, in the absence of any other name, became known as “the Chequers” by default.

This post was prompted in part, incidentally, by my extreme grumpiness at having ordered the Wordsworth Dictionary of Pub Names from Amazon and discovering when it arrived that it is simply Dunkling and Wright’s Dictionary of Pub Names rebadged, and with none of the errors in Dunkling and Wright corrected. For a book on pub names to talk about the Vital Spark pub in Glasgow, for example, and show no knowledge that the name comes from the fictional “Clyde puffer”, or steamboat, called the Vital Spark in the Para Handy stories by Neil Munroe, which have been on British television in three separate incarnations, is appallingly sloppy.

In his entertaining London Compendium (Penguin, 2003) Ed Glinert says of the Marquis of Granby on St Martins Lane:

“The pub is named after the peer who ordered 300,000 pints of porter to be drunk after winning a battle in the Seven Years War (1738-63) resulting in grateful members of his regiment naming public houses they opened on their retirement from the army after him.”

Do you happen to know if that’s true…? I can’t find any decent historical source for it anywhere.

I’ve not heard that particular tale, Bailey, and I’d be suspicious without evidence: the usual story explaining the large number (more than 30, according to Pubfinder) of pubs named Marquis of Granby, after John Manners (1725-1770), eldest son of the Duke of Rutland, army officer and politician, is that the name “is testimony to the lasting gratitude felt towards him by the disabled non-commissioned officers whom he is believed to have set up as publicans.” (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). He was certainly a generous man and very popular with the British public: the DNB says that “Much of his popularity derived from his well-publicized solicitude for his men. Edward Penny’s painting The Marquess* of Granby Relieving a Sick Soldier, exhibited in 1765, overturned conventional expectations of the history painting by showing Granby acting heroically in an act of private charity and not on the field of war. The engraving outsold even that of Benjamin West’s Death of General Wolfe.”

If you wanted my opinion, I’d say that the pub name is simply another example of the habit of naming pubs after popular heroes: there are at least three surviving pubs called the General Wolfe, for example.

Just to show that even the DNB can’t be trusted, incidentally, it claims that the hairless Granby’s famous charge at the head of his cavalry troops at the battle of Warburg on 31 July 1760, when his lost his hat during the attack (he always refused to wear a wig), is the source of the expression “to go at it bald-headed”: etymologists have comprehensively trashed the idea of this event as the origins of the phrase, which apparently started as American slang.

*sic – the Granby title is actually one of the few in the British peerage where the proper spelling is Marquis. All those pubs called the Marquis of Salisbury, or Marquis of Lorne, are wrong – it should be Marquess.

Whoa – update! Came across this, from A chronological Memoir of Occurrences for November 1759, p261

“‘Tis said the Marquis of Granby has ordered some thousand Barrels of Porter to be sent to the Army in Germany, for the Use of the common Soldiers, and at his own Expence.”

A thousand barrels is 288,000 pints, so yes, looks as if that incident certainly happened, though I doubt it, rather than Granby being a military hero anyway, was responsible for his having so many pubs named aftger him.

All thought-provoking including the detail from the Hogarth. Is that a grinning skull at the top of the ham held in the roisterer’s left hand? I wonder if Hogarth was perhaps more down on beer drinking than is often thought from comparing his frankly desolate Gin Lane.

That ham seems very small, the breeds were smaller then and probably semi-wild.

Gary

The man with the ham is meant to be a butcher: in the first version of Beer Street he is holding aloft an emaciated Frenchman, who was replaced in the better-known second version by a leg of pig. I’d not noticed a resemblance to a skull in the pattern on the top of the ham myself, but with Hogarth you never know.

Hi Martyn

Slightly unrelated reply but… I’m a postgraduate student at MMU in art and design with an interest in pub signage. I’ve recently been trying to construct something akin to a family tree; a genealogy; a typology if you like of pub names and how they may be related.

Having read your blog I’ve come to recognise that most of the books I’ve sourced information from may actually be feeding me duff information. I’m now concluding that it may be an impossible task, particularly if two pubs with the same name can possibly have different origins of that name. Does that makes sense?

Anyway, you seem to know a thing or two about pubs and the masochist inside of me would like to send you a copy of what I’ve done to date (if only for you to shoot holes through it – I know it’s going to hurt but that’s how we learn isn’t it?).

So, would you like to see it / have you seen anything like this before / and do you have an email address I can send it to?

Many thanks, Jonathan

That sounds interesting, Jonathan, send it in.

I’d love to see that! Any chance you might share it to with the masses Jonathan?

A thoroughly interesting read all round. Thanks Martyn.

Of Interest “Not Home: Alehouses, ballads, and the Vagrant Husband in Early Modern England” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies Vol 32 No 3 Fall 2002