Today is Baltic Porter Day, an event started by the Polish brewer and porter fan Marcin Chmielarz, and that gives me an excellent excuse to try to kill some Baltic Porter myths. A few facts:

● Baltic Porter, if you want to be historically accurate, should NOT be as strong as an Imperial Russian Stout. Baltic porter has its roots in the early 19th century, when Polish drinkers could not get hold of the strong porters imported from England that they had grown to love: but these were what would have been called a “double brown stout” in Britain, around 7 or 8 per cent alcohol by volume, heavy but rather weaker than the “imperial” stouts popular at the Russian court: a Polish publication from 1867 compares the strength of “piwo podwójne,” double beer, such as “porter angielski” to “Salvator or Bockbier from Munich,” which was an 8 per cent abv beer. (That’s not to say that you cannot, if you want to, brew an “Imperial Baltic Porter”. Nothing wrong with being ahistoric …)

● Baltic Porter does NOT mean – or should not mean – any porter/stout brewed in a country bordering the Baltic. Several other countries around the Baltic produce beers that are descended from the double brown stouts once shipped from London, and very fine beers many of them are, but these are, genetically still pretty close to those original DBSs. In Poland, however, many (not all) brewers developed their own twist on DBS. The expression Baltic Porter only dates from the 1990s (and there is some doubt as to who invented the term), but it has come to mean a strong black beer brewed with a typical porter/stout grain bill, at the same time using bottom-fermenting yeasts, a style specifically developed in Poland, and personally I don’t believe it should be used for any beer that doesn’t fit that description. Somewhat ironically, that means the brewery that, for a long time, was Poland’s biggest porter brewer did not brew a Baltic Porter, since its porter was top-fermented, English-style. In the beer world of Cloud-Cuckoo Land, the style of bottom-fermented porter developed in Poland is called, logically and without room for confusion, Polish Porter, but we don’t live in Cloud-Cuckoo land and thus we’re stuck with Baltic Porter as the accepted descriptor.

Anyway, for your amusement (I hope) and education (ditto), here are some extracts from the forthcoming Great Porter History Book (which may actually be finished shortly, after three years) on Baltic Porter:

By the end of the 18th century the porter brewers of London had built up a good trade with merchants in Danzig/Gdansk. The Danish Sound Toll Records, which listed the cargoes on board every ship passing through the Danish Straits, show that between 1790 and 1799 an average of nine ships a year with cargoes including “øll” [sic – the spelling at the time] or porter travelled from the Thames to what was then a Prussian-owned port. English beer was popular enough in Poland in the 1760s, during the reign of Augustus III, that a quart bottle cost four złoty when a whole barrel of locally brewed beer cost as little as six złoty. Polish brewers attempted to fight back: one, Karol Wilhelm Schmidt, spent two years in London learning all he could about English brewing, and came back around 1800 with innovations including the first wort cooler in Poland, installed in the brewery he ran in Grudziądz, 60 miles south of Gdansk.

A traveller to Poland in 1806 wrote that “English bottled porter … is to be had in all the large towns, and even at the best public-houses; at the high price, however, of about forty-five cents a bottle; and, from having passed the sea, it is commonly even of a superior flavour to bottled porter in England.” That same year, however, as part of the continuing war between Britain and France, Napoleon imposed the “Continental System” blockade on British exports. This brought a stop to shipments through the Sound of beer from London to Baltic ports such as Danzig, Königsberg and Riga from 1807 until the French Emperor’s fall in 1814. A brewer, distiller and miller in Warsaw called Michał Krembitz began brewing porter to replace the banned English imports, succeeding well enough that rival brewers accused him of illegally smuggling in genuine London-brewed beer. However, after Napoleon’s defeat and exile, trade between Britain and Poland picked up immediately: in 1815, 17 ships sailed from London to Danzig with beer among their cargoes, and Krembitz stopped brewing porter. In the three years from 1817 to 1819, 2,385,665 “kwarty” of porter were officially imported into Poland, around 16,600 Imperial barrels, plus “abundant” quantities smuggled in.

Then in 1824 imports of porter into the now Russian-owned Duchy of Poland, which covered Warsaw, were banned again, and Varsovian brewers, after a short discussion on whether the water of the Vistula could match that of the Thames, began making porter themselves in earnest. They were doubtless helped by the publication in Polish three years earlier, in 1821, of a book called Nowy Piwowar, or “The New Brewer,” by Jakub Sroczyński, subtitled “The theoretical-practical art of making various types of English beer and more famous malt liquors, as well as some new types of beer in large and small quantities,” which included descriptions of how to brew porter and “Brownstout”.

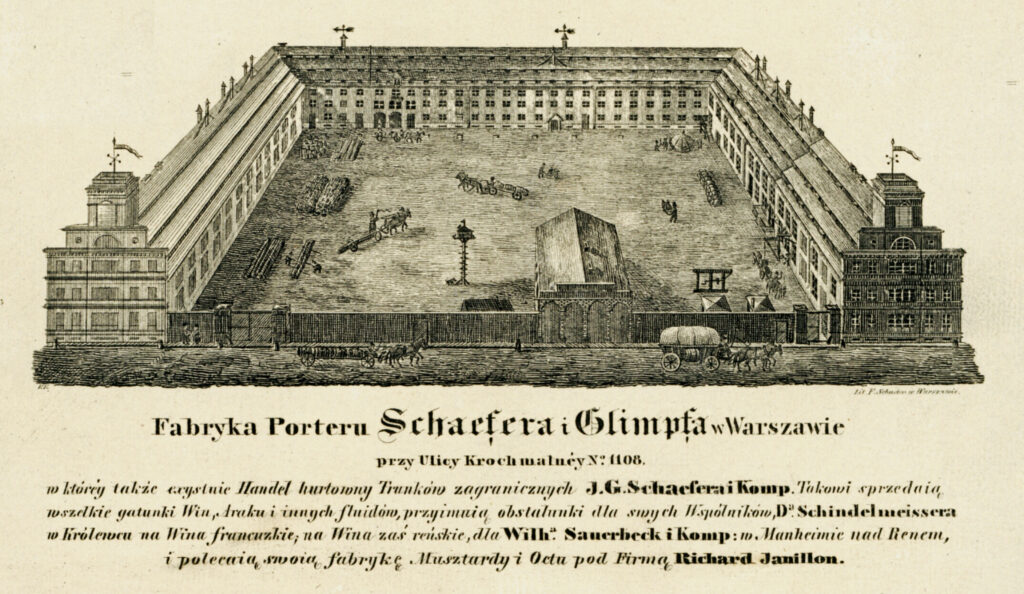

At least a dozen breweries in Warsaw turned to porter-making, including Schaefer and Glimpf in Krochmalna Street, which was started in 1826, and was “arranged in the manner of the most excellent English breweries,” and “exceeding all existing in the country”. Another concern made only English porter and ale, the Fabryka Porteru i Piwa Angielskiego (“English Porter and Beer Factory”), run by Wojciech Sommer, which opened in 1827.

Porter imports appeared to have returned by 1831, when a guide for merchants said that “large quantities” of the beer were imported through Danzig and shipped off to Warsaw and other parts of Poland, and “that brewed by Messers Barclay is the favourite.” The porter “generally arrives in casks, and is afterwards drawn off into French bottles, which contain less than the English ones; and the whole is often poured into one high tumbler glass and drank mixed with a little sugar.”

The return of imports did not stop Polish porter production. Even as “Bawarskie“, Bavarian-style dark bottom-fermented lager beer, had began to find an increasing market in Poland, porter remained popular: in 1873 at least three breweries sent examples of porter to an international exhibition in Vienna: Leon Trzetrzewński at the Steam Brewery in Tenczynek, Western Galicia; the Pawlawa Brewery near Żywiec; and Lutosławski Franciszek from Drozdów, in the north-east. Porter from Britain continued to be imported into Poland (“porter angielski” was advertised in Izraelita, a Jewish paper published in Warsaw, in 1899, for example), and to differentiate their product, Polish brewers such as Okocim called it “porter krajowy,” “domestic porter.” (The expression porter krajowy dates from at least 1866.) But as Polish brewers turned increasingly to bottom-fermentation beers with the growing popularity of lighter Bavarian and Bohemian styles, while dark beers such as porter continued to be made using top-fermentation methods for many decades, eventually much of the porter made in Poland became a bottom-fermented beer as well.

One of the longest-lasting porter brewers in Poland—albeit with gaps—was based in Warsaw. Konstanty Schiele, the Warsaw-born grandson of a grenadier from Saxony who had arrived in the guard of Augustus Wettin, Elector of Saxony and ruler of Poland from 1733 to 1763, had been working at the brewery run by Schaefer and Glimpf in Krochmalna Street, Warsaw when it fell into the hands of the Bank of Poland. In 1846 he and another Schaefer and Glimpf employee, the head brewer, Błażej Haberbusch, who had come to Warsaw from Germany to brew Bavarian-style lager beer, bought the brewery from the bank for 24,000 złoty. Despite Haberbusch’s lager-brewing background, porter continued to be part of the brewery’s line-up, with, at one point, both “zwyczajny” (ordinary) and “Extra-double” versions being brewed.

Amalgamations with four other local firms after the First World War left Haberbusch and Schiele, operating as Zjednoczone Browary Warszawskie (United Warsaw Breweries) the only brewing firm in the Polish capital, producing 10 per cent of all Polish beer. Its products at this time included Sphinx Stout, a bottled stout named for the brewery’s sphinx trademark.

In 1936 the Polish brewing historian Marjan Kiwerski indicated that unlike brewers elsewhere in Poland, who were using “German methods,” that is, bottom fermentation and lager yeasts, to make their “porter krajowi”. Haberbusch and Schiele made a “true English” beer, that is, with warm, top-fermentation methods, for a drink that was “not inferior to the original English porter.”

The brewery was used to store and distribute food during the Second World War, and as a base for the underground Armia Krajowa (Home Army), and after the Warsaw Uprising the Nazis stole all the brewing equipment. Nationalisation under the Communist Party in 1949 followed, albeit with Aleksander Schiele, born 1890, grandson of Konstanty, as director of administration. However, the brewery remained in ruins until rebuilding started in 1951, with the first beer flowing again only in 1954, under the name “Browar Warszawski,” though still using the old Haberbusch and Schiele sphinx trademark. Brewing of porter did not restart until 1960, but production of the revived beer ran through for more than four decades until 2003, the year before the brewery (by then part of the Heineken Group, after a series of takeovers) was shut for ever. However, even in 1980 production of porter was just 0.6 per cent of the brewery’s output, at 1,770 hectoliters, under 1,500 US barrels.

Porter continued to be brewed elsewhere in Poland as a bottom-fermented, strong (8 per cent abv), heavily flavored beer throughout the 20th century, though the style suffered a slump in the 1950s, as brewers in cities such as Krakow and Szczecin dropped the beer from their lists, leaving only a few examples surviving, such as the one produced by the brewery in Żywiec, in what had been Austrian Galicia. That concern had been founded by a branch of the Hapsburgs in 1852, and was exporting its porter to Hungary in 1903 under the name “Archduke Charles Stephen’s Saybusch brewery,” Saybusch being the German for Żywiec.

The English beer writer Michael Jackson brought the attention of the world to the existence of porter brewing in Poland in his World Guide to Beer, published 1977, and he is credited with inventing the expression “Baltic porter”, the name by which the style is now known, even in Poland. However, while the expression Baltic Porter seems to first appear in Jackson’s work only in 1998, in a book called, unimaginatively, Beer, the earliest use of the term in print looks to be in Bill Yenne’s Beers of the World, published in 1994, talking about the porter made by Sinebrychoff of Finland – which, as a top-fermented beer, is not a “Baltic porter” in sensu stricto (or in MY sensu stricto, anyway). Today “Porter Bałtycki” has seen a revival in Poland, with established brewers bringing it back and new-wave Polish craft brewers making sure they have a strong porter in their repertoire.

(Hat tip to Marek Kamiński for correcting my Polish grammar)

Glad to hear your magnum opus on Porter is coming on well.

As you mentioned Imperial Russian Stout in the opening; I recall going to Moscow to do a job of work in 1994;

Black beer wasn’t really a thing in the UK then (though I do vaguely remember UK Russian Stout from the 70s and will always try any black beer than comes my way). Anyway, the only beer available in the hotel was small tins of Heineken for £4.50 (yes in 1994) and a Tuborg Keg in a gold livery tap/branding which was black and I’d then assumed a Russian Stout. Any idea what it was Martin? I’ve never seen it before or since.

There used to be a s trong stout issued under the Tuborg name – I drank it in Germany many years ago – and I’m guessing that was what you found.

One Baltic Porter most definitely has its roots in UK DBS. But not a London one. Karl Jacobsen, sonof the Founder of Carlsberg, served an apprenticeship at William Younger in Edinburgh. When he returned to Copenhagen he brewed several UK-style beers, including one called DBS. Which was also the name of Younger’s principal Stout.

A great article that would be even grander if not for a few grammatical errors–in Polish 🙂 Nouns and adjectives come in no less than seven cases here and in your context you really should use the nominative: “porter krajowy”, not “porteru krajowego”; “zwyczajny”, not “zwyczajnego”; “piwo podwójne”, not “piwem podwójnem” etc. Just a minor gripe, ofc 🙂

Now corrected, I believe.

Almost there 🙂

<> should read <>

<> should read <>

Other than that, just great (y).

Oh well, the comment form doesn’t like my bracketing style; I’m rewriting it then:

Almost there 🙂

== to make their “porteru krajowego,”== should read == to make their “porter krajowy,”==

==An advertisement for “porter krakowy”== should read ==An advertisement for “porter krajowy”==

Other than that, just great (y).

[…] not as they are. In stylistic news historical-wise, Martyn posted an excerpt from his upcoming book on stouts and porters arguing that Baltic Porters are not really […]

Hi, Martin!

Do I understand right that your point of view is that Baltic porter came from Poland, not from Baltic countries, Finland and St.Petersburg? Michael Jackson decided to name it not Polish porter, but Baltic Porter, because… just because. May I also kindly ask for some historical evidence that “imperial” stouts” were “popular at the Russian court”? Could you please explain how London porter (“working class beer”) became so popular at the Russian court??? Could you name any Russian Tzar who used to be a porter fan? (I wonder) Thank you.

Certainly, Yuri – I don’t make this stuff up, it’s always written based on specific sources, which I don’t name, generally, in the blogs, but which are always named and references in books and academic articles …

Every year Catherine II ordered a large quantity of stout black beer from London for the needs of her court in St Petersburg (Mika Rissanen and Y. Tahvanainen, Istoriya piva: Ot monastyrey do sportbarov (History of beer: From monasteries to sports bars), Moscow, 2017, p6)

In 1791, when Great Britain was threatening to end trade relations with St Petersburg over Russia’s war with Turkey, the Empress voiced alarm to her advisers at the possibility of supplies of porter being cut off. (Yekaterina II i G. A. Potemkin. Lichnaya perepiska 1769-1791 (Catherine II and GA Potemkin, Personal correspondence 1769-1791), Direct Media, Moscow, 2010, p1296)

The landscape painter Joseph Farington wrote in his diary for August 20 1796: “I drank some Porter [Mr Lindoe] had from Thrale’s Brewhouse. He said it was specially brewed for the Empress of Russia and would keep seven years.” – James Greig, ed, The Farington Diary by Joseph Farington, Volume 1, Hutchinson & Company, 1923, p163

Tsar Alexander I specifically allowed the importation of porter into Russia because he had acquired a taste for it on his three-week visit to England in 1814, and “it was a favourite beverage with him.” – The Gentleman’s Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, London, England, Volume 91, Part 1, 1821, p513

As for Michael Jackson and Baltic porter, the current evidence is that he didn’t invent the name, and Bill Yenne was using the expression before him. Michael and Bill were using the expression to refer to any strong porter brewed in the Baltic region that was derived from the Double Brown Stout porters shipped from London to the Baltic, but it’s my belief that Baltic Porter as a name ought to be restricted to those porter-like beers brewed with lager yeasts that developed in Poland, and that in any case a better name for them is Polish porter, because until the Second World War such beers were resticted to Poland. Others may disagree!

For nearly 40 years, I lived very close to the historical Royal Dockyards at Deptford, near the modern statue (a gift from the people of Russia) of Peter the Great.

It is well documented that he lived in John Evelyn’s house at Sayes Court, and attended the Royal Dockyards for about 3 months, learning how to build ships.

It may be a myth, but it is said that the Tsar acquired the taste for porter at this point, and enjoyed it after a day’s work in the shipyards. If true, this is the point where a Tsar came to enjoy the same drink as the workmen, and took that taste back to St Petersburg when he returned.

If it’s a myth, well, it’s a nice one.

Dear Rod!

Peter The Great came to London on 11th of January 1698 and left it on 24th of April. There is no evidence that he drank porter there. If to take into consideration that the first mention of porter was made by Nicholas Amhurst in 1721 in “Terræ-filius: or, the Secret History of the University of Oxford”, Peter the Great could not drink porter in 1698. But if to believe that the first mention of porter was in 1996 in “An Essay in Defence of the Female Sex” by Judith Drake, picture with Peter The Great with mug of porter in his hand seems to be more realistic. In Russian archives I could find out a paper dated 25th of August 1700 that Englishman Henry Stiles came to Moscow (St.Petersburg was not constructed yet) to ask for money refund of the sum, which had been borrowed by Peter being in London. At the same time Henry Stiles asked also for compensation the costs of transportation of a brewer from England and back to England, brewer’s salary for a year, his accommodation and food there, and the costs for work of interpreter for the brewer. That means that Henry Stiles helped Peter the Great to get some unknown yet brewer to settle pro-British brewery and brew for a year in Moscow. Was it porter or not we do not know yet. But Peter the Great in his letters to his wife Catharine I used very strange construction “alebier”… May be it was a sort of synonym for porter, May be…

Sorry for mistake: “An Essay in Defence of the Female Sex” by Judith Drake was published in 1696, not in 1996.

“Peter The Great came to London on 11th of January 1698 and left it on 24th of April. There is no evidence that he drank porter there.”

I said that it could be a myth, but the fact that there is no evidence that he drank it doesn’t mean he didn’t – just that no writen account of it was made at the time, or has been lost.

“If to take into consideration that the first mention of porter was made by Nicholas Amhurst in 1721 in “Terræ-filius: or, the Secret History of the University of Oxford”, Peter the Great could not drink porter in 1698. ”

Peter could have drunk Porter in 1698 – this is the early 18th century, and the fact that no-one (that we know of) mentioned this new black beer in 1698 proves nothing. The fact is that we don’t actually know when Porter first started to be brewed, but it is not impossible that it could have been available in 1698.

“That means that Henry Stiles helped Peter the Great to get some unknown yet brewer to settle pro-British brewery and brew for a year in Moscow. Was it porter or not we do not know yet. ”

No, exactly – we don’t know. I said it could be a myth, didn’t I?

What we do know from this is that it is true that Peter acquired a taste for London beer, to the point where he set up a brewery in Moscow, with an English (probably) brewer. This is presumably where the introduction of English-style beer into the Imperial court occured. The beer may or may not initially have been Porter.

As I said, if it’s a myth, it’s a nice one, and nothing you have said here is actual evidence that Peter could not have drunk Porter during his time in London.

Hi, Rod!

“…with an English (probably) brewer…”

Well, not probably, but exactly English brewer. At least this is written in Peters’s papers.

And it was not imperial court yet, but Moscowian court, so the English brewer brewed in Kremlin.

“As I said, if it’s a myth, it’s a nice one, and nothing you have said here is actual evidence that Peter could not have drunk Porter during his time in London”.

Yes, that’s a nice myth and I want tp believe in it. That’s why I try to find any evidence of it… alas still in vain. That’s what I wanted to say.

“not Imperial court yet…”

Was Peter not Tsar at this point?

Rod,

““not Imperial court yet…”

Was Peter not Tsar at this point?”

Yes, he became a Tsar in 1682, but he proclaimed himself as Emperor in 1721 only.

So imperial capital was St.Petersburg, which was founded in 1703, in 1700 Peter lived in Moscow Kremlin. The brewery was inside Kremlin also.

As to Judith Drake’s porter’s ale – I really believe that this is the earliest known mention of porter. I could find it occasionally pair years ago.

“alebier” probably mean Burton upon Trent-style pale ale (the pre-IPA sweetish Burton Ale the town was originally famous for), which competed with porter in Russia.

I hope so. I you are interested I can send you these letters. Alebier is also use in several Customs lists.

Dear Martin,

Let me disagree with you:

1. «Every year Catherine II ordered a large quantity of stout black beer from London for the needs of her court in St Petersburg» Is this quote from Rissanen and Tahvanainen a historical evidence or a typical copypast from article to article about porter or Russian Imperial stout? What is “a large quantity” and what was the needs of imperial court? You always work with concrete documents to make some conclusion, don’t you? So why you talk about popularity of working class porter at Russian court? Any documents? No, there are no documents at all to prove these statements.

2. Well… I do understand what you are talking about. But this is not about importing of British beers at all. This document is not a letter, but a quote from the diary of Alexander Khrapiovitsky, cabinet-secretary of Catherine II. He wrote all the papers for Catherine II. So this is not her letter, but once again a note in a diary of Khrapovitsky. What was written there exactly? “9 апреля. Сказали, что пива и портера не будет; но сего же утра Князь с Графом Безбородко составили какую-то записку для отклонения войны. Князь был ввечеру у Государыни, а оттуда пошел на исповедь” If you don’t mind I will try to translate: “9th od April (1791). They said (Catherine II said) that there would be no beer and porter, but this morning the Prince (Potemkin) and Count Bezborodko drew up a note to reject the war. The prince was in the evening with Her Majesty, and from there he went to confession”. It is very hard to insist that this proves any deliveries of porter from Britain to the court. It says that it would nor beer neither porter on 09th of April 1791 at lunch or at dinner, or at supper… Who knows? At the same time huge British colony existed in Galerienhof, district in St.Petersburg in two blocks western from Winter Palace, where from porter came to Russia. And there was dozen of English breweries operating in St.Petersburg in Catherine II epoch and brewing London style porter here on spot. So there was no reason to voice alarm at the possibility of supplies of porter being cut off.

3. The diary of Joseph Farington is just a diary. Any papers from Thrale’s Brewery? No, of course. Josef made a note in August 1796 about the porter for Empress which would be kept for 7 years, but Catherine II died in November 1796 in age of 67. She could not taste it, even if it existed.

4. Tsar Alexander I allowed the importation not only porter into Russia, but all the British goods after Napoleonic blockade. Russia was ally of France prior the war with Napoleon in 1812 and supported this blockade. But after the war importation from Britain restarted. Yes, Alexander visited England from 06th till 27th of June 1814 and (from 7th till 22nd of June he was in London) and for sure he could taste London porter there. But it could not be a surprise for him cause Britons had been brewing London porter for decades in St.Petersburg. If it was real surprise for him – that proves that there were no huge deliveries of British porter to Russian court or porter was not so popular at Russian court.

5. I met with Michael Jackson twice and both times we talked about Baltic porter, RIS and kvass of course. So he told me that the term Baltic porter had been suggested by him after travelling to Russia and Baltic states, not Poland. And I do believe him. He used this term in some articles. And, yes, I know that it was Bill Yenne’s “Beers of the World” in 1994 before Jackson’s “World Guide to Beer», but Bill could borrow the tern from Michael’s articles, couldn’t he?

6. The first bottom fermented porter was made at Carlsberg with lager yeasts, then it came to St.Petersburg not Poland. After Crimean war almost all Britons moved from St.Petersburg and British brewers were replaced by Germans. And Germans started ferment porters by lager yeasts. Much more Germans lived in St.Petersburg than in any Polish town. St.Basil island in St.Petersburg spoke only German for instance. And in St.Petersburg there were much more so-called porter-houses (pro-British pubs) than in whole Poland. So German brewers were forced to brew porter in absence of Britons due to high local demand. BTW when Niels Hjelte Claussen applied for his patent 813199 on 17th of May 1904 and publish hid article “On a Method for the Application of Hansen’s Pure Yeast System in the Manufacturing of Well-Conditioned English Stock Beers” in “Journal of the Institute of Brewing” # 10 in 1904 (p. 308-331), it was H. Seyffert from Kalinkin Brewery in St.Petersburg arguing that he for years had been fermenting his porters by lager yeasts and then using wild yeasts foe secondary fermentation…

7. If we take a look at porter label in pre-revolution period we may see two descriptions of styles in English and in Russian. In English it is always “Imperial Extra Double Stout” and in Russian it is Портер (just Porter). So prefiguration of Baltic Porter was not “Double Brown Stout”, but “Imperial Extra Double Stout” (if to be final meticulous).

8. During Soviet period porter fermented in both ways – top and bottom. To make process faster it was made as top-fermented one. When CCTs replaced old fermenters almost at all soviet breweries in 70th-80th porter became finally lager.

Regards,

Yuri

While bog-standard Porter was a working class drink, Strong Stout most definitely wasn’t. It was way too expensive. It was a high-class beer made in small quantities.

For some reason, in Continental Europe the term Porter was mostly used, even though the beers to which they were applying the term were considered Stouts in England.

Carlsberg Porter was most definitely called Double Brown Stout. I’ve seen the brewing records. Carl Jacobsen nicked the name and the recipe from William Younger, where he served an apprenticeship in the 1860s. I’m sure that, at least initially, it was top-fermented. As were the other British styles he brewed, such as Mild Ale and Pale ale.

Lots of different names were given to Stouts. The official name of the Barclay Perkins Russian Stout was Imperial Brown Stout. Double Stout, Triple Stout, Foreign Extra Stout, Double Brown Stout, Imperial Stout. There’s not a great deal of logic to how they were used.

Barclay Perkins claimed that their Russian Stout had been brewed for the Russian Court. I certainly wouldn’t rely on that, however, knowing how unreliable breweries’ accounts of their own histories can be.

Hi, Ron!

If we consider that name “porter” goes not from Dutch “poorter” but from working class profession it is very hard to explain how the beer with this name could become popular at Russian Imperial court and high society. Its popularity at the court and huge deliveries is more or less exaggeration based mostly on Barclay Perkins advertising in 1920-s, when Russian monarchy was destroyed already. Did they drink porter in Winter Palace? Yes, they did time to time. Was it the drink #1 at the court? No, never… Everybody talks about Catherine II… but in fact she drank beer very seldom. There are quite many evidences that she drank 2-3 cups of strong coffee in morning, glass of “madera” or “reinvein” at lunch, she was fond of kvass and cranberry-drink… But you can not find anything about her addiction to porter. So the story with Joseph Farington’s diary is a nice bullshit fairy tale. Once again Catherine II was lying in her grave in Peter&Paul Cathedral when this concrete porter was ready for her according to the story.

Was porter popular among Russian middle class? Yes, extremely. And mostly because of local anglomania and English colony in Galerienhof, district in St,Petersburg. Only in St.Petersburg in the middle of XIX century there were pair hundred so-called porter-houses, where both British and local porters were served. Locally brewed porter was of two types English porter and Russian porter. Russian English porter brewed with sugar and was more expensive and strong than Russian Russian porter, which was brewed without sugar. But nobody used term “stout” in pre-label period, but only “porter”. When labels appeared, porter started marked as “Imperial Extra Double Stout” mostly. I will send you the examples of labels by e-mail, if you don’t mind.

Regarding Carlsberg porter. I’ve been to Carsberg archive couple years ago and made photos of their old labels with lager stout and lager porter. I will send you these photos too. I am sure that lager stout is NOT top-fermented beer 🙂 The fact that Carlsberg porter was lager one is proved by Niels Hjelte Claussen’s work “On a Method for the Application of Hansen’s Pure Yeast System in the Manufacturing of Well-Conditioned English Stock Beers” in which he suggested to make porters by lager yeasts, filter them, and after filtration secondary ferment them by Bretts.

As to Barclay Perkins you are a better specialist than I and I have to shut up, but no… I wont 🙂 There is no evidence of direct deliveries of Barclay Perkins to Russian court, no contract, no papers, no such a name in court suppliers list. But of course Barclay Perkins was at Russian market and probably several bottles reached the court.

Going to send labels of Russian porter…

Regards,

Yuri

There’s a brew of DBS on 18th September 1871 which specifically says that it uses Evershed yeast – a brewery in Burton that Carl Jacobsen also worked at. 100% certain early Carlsberg Porter was top fermented.

You can see the relevant Carlsberg brewing record here:

https://barclayperkins.blogspot.com/2021/02/another-weird-technical-post.html

“If we consider that name ‘porter’ goes from working class profession it is very hard to explain how the beer with this name could become popular at Russian Imperial court and high society.”

Why? George Washington and other upper-class Americans drank and thoroughly enjoyed porter, the Prince Regent in Britain is recorded as drinking porter – it was a tasty and refreshing drink, and it should not be surprising that it was widely enjoyed by all classes.

“Catherine II was lying in her grave in Peter & Paul Cathedral when this concrete porter was ready for her according to the story.”

As I said earlier, the date of Faringdon’s story versus the date Catherine II died is entirely irrelevant to the truth of the tale: nobody said this was the first or earliest brewing of a strong porter sent to Russia. Super-strong export porters had been brewed since at least the early 1780s: in 1782 the stock of a wine merchants and porter exporter in Wapping, east London included “221 Butts Old Porter, brewed of peculiar strength for exportation, as an extra price.” (Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, London, England, 9 February 1782, p4)

“Its popularity at the court and huge deliveries is more or less exaggeration”

In the spring of 1789 the Russian authorities, then fighting a war with Sweden, ordered from a brewery in Southwark (probably Thrale’s/Barclay’s) 1,000 barrels of porter as supplies for the Baltic Sea fleet in Kronstadt and Reval (Tallinn), which took three English merchant ships to bring over from England. (Whitehall Evening Post, London, England, 16 June 16 1789, p 4; and Maryland Gazette 17 September 1789, p3) So the Russian court was certainly used to ordering large quantities of porter.

“based mostly on Barclay Perkins advertising in 1920-s, when Russian monarchy was destroyed already. “

The story dates back a century before that: in 1829 Thomas Allen wrote that Barclay’s porter “used to be in great request with the empress Catherine at Petersburgh.” (Thomas Allen, The History and Antiquities of London, Westminster, Southwark and Parts Adjacent, vol IV, London, England, 1829, p538) “Barclay Perkins and Co.’s imperial double stout porter from the butt” is mentioned in 1822 (Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen’s Land Advertiser, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, Saturday December 21 1822, p2) And the beer was being called Barclay’s Russian Imperial Stout in 1907, when the Russian monarchy was still going strong (The Standard, London, Monday October 21 1907, p9)

“Niels Hjelte Claussen … suggested to make porters by lager yeasts, filter them, and after filtration secondary ferment them by Bretts.”

That was 1904 or so, a century after the period we are discussing. And just because Claussen suggested it, that doesn’t mean they did it.

“There is no evidence of direct deliveries of Barclay Perkins to Russian court, no contract, no papers, no such a name in court suppliers list.”

There wouldn’t be. They sold to independent shippers, such as Benjamin Kenton and A. Le Coq.

Martin,

Why? George Washington and other upper-class Americans drank and thoroughly enjoyed porter, the Prince Regent in Britain is recorded as drinking porter – it was a tasty and refreshing drink, and it should not be surprising that it was widely enjoyed by all classes.

Right! It was not working class drink. That’s what I want to say. I could not be served in noble houses worldwide being working class beer. From the other hand we can not find direct evidences of huge quantities of porter served at the court.

In the spring of 1789 the Russian authorities, then fighting a war with Sweden, ordered from a brewery in Southwark (probably Thrale’s/Barclay’s) 1,000 barrels of porter as supplies for the Baltic Sea fleet in Kronstadt and Reval (Tallinn), which took three English merchant ships to bring over from England. (Whitehall Evening Post, London, England, 16 June 16 1789, p 4; and Maryland Gazette 17 September 1789, p3) So the Russian court was certainly used to ordering large quantities of porter.

Wait… This was started in June 1788. And Britain supported Sweden in this war. Do you really think that Russian court made this order from the enemy? Which concrete Russian authorities we talk about? Could you please share this article?

This “order” came just after First Rochesalm sea battle in which Russia won and Sweden lost 39 ships from 49 participated in the battle. So this is very interesting episode with porter.

And the beer was being called Barclay’s Russian Imperial Stout in 1907, when the Russian monarchy was still going strong (The Standard, London, Monday October 21 1907, p9)

This is something very new for me. Could you also share this article?

Porter was popular in St.Petersburg and in Russia in general in XVIII-XIX centuries.

Does Imperial means Empire or high quality? Any evidence of serving Barclay’s Russian Imperial Stout at Nikolai II table? Or may be this is just early XX century marketing???

BTW Nikolai II banned vodka, wine and all strong beers including porter in the first days of I World war. He was not the fan of porter, but the fan of sobriety and prohibition, but who care about it in England in that days and now defending Russian Empire court as a major reason of creating a style?

Right:

“Why you talk about popularity of working class porter at Russian court? Any documents? No, there are no documents at all to prove these statements.”

Ah, but there are: there’s excellent evidence that porter was popular with the Russian upper and noble classes. The traveller William Coxe, who visited St Petersburg in 1778, recording his experiences of dining at the homes of noble Russians, said: “I never tasted English beer and porter in greater perfection and abundance.” (William Coxe, Travels in Poland, Russia, Sweden and Denmark, Vol II, London, England, 1784, p151) A young expat from London, James Brogden, wrote to his sister from St Petersburg in 1787 about an upper-class ball he had attended in the city: “The supper is very elegant, but so much in fashion is everything English that Beefstakes, Welsh Rabits & Porter is the most fashionable meal.” (Anthony Cross, “By the Banks of the Neva”: Chapters from the Lives and Careers of the British in Eighteenth-Century Russia, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p25). Why did a drink originally brewed for the London working classes achieve such popularity with the Russian aristocracy? For the same reason that George Washington and other upper-class Americans drank porter: because it was a delicious and satisfying beverage.

I fail to understand why you are dismissing Faringdon’s statement as “just a diary”. It’s as much evidence as your anecdote about what Michael Jackson said to you. And the date of Catherine’s death is entirely irrelevant: nobody said that what Faringdon was drinking was the first very strong stout Barclay’s had brewed and sent to Russia.

“There was dozen of English breweries operating in St. Petersburg in Catherine II epoch and brewing London style porter here on spot.”

I’d like to see the evidence for that many English breweries. A list of enterprises in St Petersburg drawn up in 1794 showed 13 breweries, three run by (unnamed) British brewers and “many” others by Germans and Russians. (Anthony Cross, Britantsy v Peterburg: XVIII vek (Britain and St Petersburg in the 18th century), St Petersburg, Russia, 2005, p82) Considerable quantities of porter were imported from Britain into Russia: the average imports of porter and English beer into St Petersburg between 1780 and 1790, according to William Tooke, chaplain to the English merchants in the Russian capital, were worth 262,000 roubles a year. (William Tooke, The Life of Catharine II: Empress of Russia, fourth edition, vol II, London, England, 1800, p23) Certainly porter brewing was taking place in Russia: the German traveler Heinrich von Storch wrote in 1801 that in St Petersburg “A great part of the porter which is sold under that name is brewed here.” (Heinrich Friedrich Von Storch, The Picture of Petersburg, London, England, 1801, p120) The only names of porter brewers I have been able to discover, however, are the Cazalets by the Staro Kalinkin bridge, who were English Huguenots, and Abraham Krohn and Friedrich Danielson (or Danielsen): Krohn was born in what was then Swedish Pomerania, Danielson appears to be a mystery but may be from Tallinn. Krohn and Danielson brewed both porter and ale, and in 1805 they were appointed brewers to the Imperial Court: evidence itself that the court drank porter. (Kalinkin Petersburg: History of the brewery, bit.ly/kalinkinhistory)

“Tsar Alexander I allowed the importation not only porter into Russia, but all the British goods after Napoleonic blockade.”

But in 1822 the Russian government announced a long list of banned imports, with “almost every article of British manufacture prohibited,” which included “foreign ale and cider” but allowed in “porter in casks and bottles”. (New Times, London, England, March 4 1822, p3) The inference is that while breweries in Russia were certainly making porter, it was not regarded by those with the power to draw up the rules on imports as being as good as the British-brewed porter. Yes, Alexander could have drunk Russian porter, but it looks as if his visit to London may have been his first real exposure to the London-brewed version, and he liked it enough to not ban it along with everything else from Britain. That doesn’t prove he never drank London porter in St Petersburg before 1814, though.

“Bill could borrow the tern from Michael’s articles, couldn’t he?”

Without evidence that’s just speculation. There’s a huge amount of MJ’s writings, including articles, on the net: if he WAS using the term “Baltic Porter before Bill Yenne, I would have expected to see it there somewhere.

“The first bottom fermented porter was made at Carlsberg with lager yeasts, then it came to St. Petersburg not Poland.”

Without evidence, I don’t believe Carlsberg was brewing bottom-fermented porter in the 19th century: as Ron said, in 1868 Jacob Christian Jacobsen was convinced there was a market in Denmark for English-style top-fermented beers, and also an opportunity to export them from Denmark, and sent his son Carl off to Britain at the age of 26 to learn how to brew porter and India Pale Ale. He would not have been trying to compete against English porters by using non-English methods of porter brewing. In any case, Russian porter at the end of the 19th century was brewed using German-style double-decoction mashing, but top-fermentation: in 1898 L. N Simonov wrote that while for most beers in Russia “mainly bottom fermentation is used,” for black beers Russian brewers used top-fermenting yeasts, “because bottom fermentation is not suitable for these varieties.” (L.N. Simonov, Пивоварение (заводское и домашнее), Квасоварение и Медоварение (“Brewing [factory and home], Kvass Brewing and Honey production”), St Petersburg, Russia, 1898, pp408-9

“it was H. Seyffert from Kalinkin Brewery in St.Petersburg arguing that he for years had been fermenting his porters by lager yeasts and then using wild yeasts foe secondary fermentation”

Well, Simonov does not appear to be aware of this, and his informant on porter brewing in Russia was M.S. Pumpyansky, director of the Kalashnikov brewery in St Petersburg, who must have known what the Kalinkin brewery was doing. If you have a reference from Seyffert backing that claim up, I would be delighted to see it.

“prefiguration of Baltic Porter was not ‘Double Brown Stout’, but ‘Imperial Extra Double Stout'”

Simply not true. Strong porters brewed in Russia were called “Imperial Extra Double Stout” because that’s what they were: the strongest top-end members of the porter family, with an OG of 1100 or more. The stouts brewed in Poland, and therefore the forerunners of Baltic stout, the evidence is clear – I quote it in this blog piece – were Double Stout (or Double Brown Stout – the name is interchangeable) strength, 1075OG or so. The advertisement below is typical of the beers made by a London brewer, and the prices indicate the strengths: porter, 1045-1055 OG, single stout 1055-10650G, double stout 1070-1080OG, Imperial stout 1090-1110OG. The Imperial stouts were labelled in Russian “Портер” because they were members of the porter family.

“During Soviet period porter fermented in both ways – top and bottom. To make process faster it was made as top-fermented one.”

Not true. Obshche Soyuznyy Standart 350, the official rules issued by the NKPP, the Soviet food industry commissariat, in 1938, specifically defined porter as “pivo verkhovogo brozheniya,” top-fermented beer. It was not until the Soviet Union invaded Poland in September 1939 and seized the city of Lviv, allowing Soviet brewers to take a look at how the city’s big brewery made porter, that Soviet practice changed: a book was published in the Soviet Union called Tekhnologiya pivovarennogo proizvodstva, “Technology of brewing production,” by Peter Mikhailovich Maltsev, which devoted space to the brewing methods of the Lviv brewery. Under the influence of Maltsev’s book, by 1946 it appears all beers in the country, including porter, were being made using cold bottom-fermentation. (Pavel Yegorov, “Baltic porter in Russia,” Profibeer, February 26 2018, accessed at bit.ly/egorovporter)

Dear Martin!

I will try to answer in parts…

Ah, but there are: there’s excellent evidence that porter was popular with the Russian upper and noble classes. The traveller William Coxe, who visited St Petersburg in 1778, recording his experiences of dining at the homes of noble Russians, said: “I never tasted English beer and porter in greater perfection and abundance.” (William Coxe, Travels in Poland, Russia, Sweden and Denmark, Vol II, London, England, 1784, p151) A young expat from London, James Brogden, wrote to his sister from St Petersburg in 1787 about an upper-class ball he had attended in the city: “The supper is very elegant, but so much in fashion is everything English that Beefstakes, Welsh Rabits & Porter is the most fashionable meal.” (Anthony Cross, “By the Banks of the Neva”: Chapters from the Lives and Careers of the British in Eighteenth-Century Russia, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p25). Why did a drink originally brewed for the London working classes achieve such popularity with the Russian aristocracy? For the same reason that George Washington and other upper-class Americans drank porter: because it was a delicious and satisfying beverage.

This is true. Cox starts «The nobles of Petersburgh are no less than those of Moscow…» But what about the court? Do you have any description of porter at a ball in Winter Palace?

From the other hand the whole quote sounds in this way: “The common wines are claret Burgundy and Champagne, and I never tasted English beer and porter in greater perfection and abundance”. Try to imagine high-class Champagne and working class-porter on the same table in aristocratic house. How could it be? It could be in a case porter never was working class beer. Not in Russia, not in England.

Well, I do believe that etymology of “porter” goes out from Dutch “poorter”, not from a working-class profession. Dutch had some influence both on Russian and English languages. We still use Dutch “apelsin” (apple from China) for orange, and almost all engineering terms are Dutch ones brought by Peter The Great from his first travel.

As to the next quote from Antony Cross – it describes parties in English colony in Galerienhof organized by English merchants, not the common life of Russians. doesn’t it?

I fail to understand why you are dismissing Faringdon’s statement as “just a diary”. It’s as much evidence as your anecdote about what Michael Jackson said to you. And the date of Catherine’s death is entirely irrelevant: nobody said that what Faringdon was drinking was the first very strong stout Barclay’s had brewed and sent to Russia.

Both notes from Faringdon’s and Khrapovitsky’s diaries do not prove anything, like the letter of 20 y.o. francophone (who crossed English channel for 8 days in his previous letter) and should not be a basement for working class theory of porter’s name.

“There was dozen of English breweries operating in St. Petersburg in Catherine II epoch and brewing London style porter here on spot.”

I’d like to see the evidence for that many English breweries.

It is very hard to do this in comments. If you don’t mind I’d like to send you by mail.

“A list of enterprises in St Petersburg drawn up in 1794 showed 13 breweries, three run by (unnamed) British brewers and “many” others by Germans and Russians. (Anthony Cross, Britantsy v Peterburg: XVIII vek (Britain and St Petersburg in the 18th century), St Petersburg, Russia, 2005, p82)”

Cross took this information not from some “list of enterprises in St Petersburg” but from the book by Johann Gottlieb Georgi “Description of capital town St.Petersburg” (1794, pages 243-244). I can disagree with this statement, cause I found more.

At the same time Georgi says that only one Russian brewer was written in a Guild. That means that a Russian owner of a brewery in St.Petersburg usually hired foreign brewer, most probably English one, cause the quote of Georgi finished by: “Кроме аглинского прочие иностранные пива не употребительны” (Except English, other foreign beers are not consumed here).

Considerable quantities of porter were imported from Britain into Russia: the average imports of porter and English beer into St Petersburg between 1780 and 1790, according to William Tooke, chaplain to the English merchants in the Russian capital, were worth 262,000 roubles a year. (William Tooke, The Life of Catharine II: Empress of Russia, fourth edition, vol II, London, England, 1800, p23)

How much this is in litres? What was the cost of working-class drink per litre for Russian aristocracy?

I have statistic for later periods:

1820 – 2605 hogsheads х 249,54 l = 650 052 l

1821 – 2754 hogsheads х 249,54 l = 687 233 l

1825 – 1094 hogsheads x 245,49 l = 268 566 l

1826 – 898 hogsheads x 245,49 l = 220 450 l

1827 – 1005 hogsheads x 245,49 l = 246 717 l

1828 – 993 hogsheads x 245,49 l = 243 772 l

1829 – 1064 hogsheads x 245,49 l = 261 201 l

And so on…

Figures are taken from Statistic Revue on Foreign Trade (G. Nebolsin, 1850, pages 279-280). This is import for whole Russian Empire including Poland, Baltics, Finland and other regions.

According to population census 1745—1751 in Russia (without Poland and Finland) there were 5 378 203 males in European part and 1 411 488 males in Asian part. Nobody calculated females in that time,

Prior war in 1812 with Napoleon population was 41 mln. After after war and getting finally Finland, Poland, Baltic – 45 mln in 1815.

So is it a big volume of porter or not for this population?

Certainly porter brewing was taking place in Russia: the German traveler Heinrich von Storch wrote in 1801 that in St Petersburg “A great part of the porter which is sold under that name is brewed here.” (Heinrich Friedrich Von Storch, The Picture of Petersburg, London, England, 1801, p120) The only names of porter brewers I have been able to discover, however, are the Cazalets by the Staro Kalinkin bridge, who were English Huguenots, and Abraham Krohn and Friedrich Danielson (or Danielsen): Krohn was born in what was then Swedish Pomerania, Danielson appears to be a mystery but may be from Tallinn. Krohn and Danielson brewed both porter and ale, and in 1805 they were appointed brewers to the Imperial Court: evidence itself that the court drank porter. (Kalinkin Petersburg: History of the brewery, bit.ly/kalinkinhistory)

Right Abraham Krohn was from Rugen Island. In 1478 it became Pomeranian and after Westfälischer Friede in 1648 became Swedish. But Danielson was from Finland from Tavastehus (Hämeenlinna), which was Swedish one also. So Friedrich was Danielson, not Danielsen.

They both opened a second brewery in Moscow in 1821.

BTW Nikolai Danielson the grand son on Friedrich Danielson translated Karl Marx’s “Capital” in Russian.

And BTW near by Old Kalinkin bridge there was also another English brewery of Stevens and Smith. It is clear from newspapers of 1771.

And there is also a petition of English brewer Smith of 1667 to State Senate to settle up a brewery for brewing beer in “English manner” with asking for decreasing taxes. He was allowed to settle a brewery but on a common basis with paying all the taxes, because beer in “English manner” was not something special in St.Petersburg and there was no reason to decrease taxes.

“Tsar Alexander I allowed the importation not only porter into Russia, but all the British goods after Napoleonic blockade.”

But in 1822 the Russian government announced a long list of banned imports, with “almost every article of British manufacture prohibited,” which included “foreign ale and cider” but allowed in “porter in casks and bottles”. (New Times, London, England, March 4 1822, p3) The inference is that while breweries in Russia were certainly making porter, it was not regarded by those with the power to draw up the rules on imports as being as good as the British-brewed porter. Yes, Alexander could have drunk Russian porter, but it looks as if his visit to London may have been his first real exposure to the London-brewed version, and he liked it enough to not ban it along with everything else from Britain. That doesn’t prove he never drank London porter in St Petersburg before 1814, though.

Are we talking about Napoleonic blockade of Britain, which came to an end in 1812 or Protection Customs Tariff of 1822 prepared by Egor (Georg Ludwig) Kankrin, according to which 21 items were banned for export and 301 items banned for import?

If the last one it is not against British products. It banned in particular import of hard liquers, vodkas, beer vinegar and not “foreign ale and cider”, but “any beer and cider”, not “foreign” and not “ale”, but “any” and “beer”.

You may find it here on page 47.

https://books.google.ru/books?id=sjpFAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA47&dq=%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%84+1822#v=onepage&q=%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%84%201822&f=false

“Bill could borrow the tern from Michael’s articles, couldn’t he?”

Without evidence that’s just speculation. There’s a huge amount of MJ’s writings, including articles, on the net: if he WAS using the term “Baltic Porter before Bill Yenne, I would have expected to see it there somewhere.

I think we should ask Bill. I will do it.

“The first bottom fermented porter was made at Carlsberg with lager yeasts, then it came to St. Petersburg not Poland.”

Without evidence, I don’t believe Carlsberg was brewing bottom-fermented porter in the 19th century: as Ron said, in 1868 Jacob Christian Jacobsen was convinced there was a market in Denmark for English-style top-fermented beers, and also an opportunity to export them from Denmark, and sent his son Carl off to Britain at the age of 26 to learn how to brew porter and India Pale Ale. He would not have been trying to compete against English porters by using non-English methods of porter brewing.

This will be a long discussion I predict. I hope you know the story of father and son. Father send his son to Britain to learn British brewing, But son returning from Britain started brewing in lager way using trademark of father. Conflict came out into Gamle and Ny decision.

Once again I can send you labels of Ny Carlsberg with “lager stout” sign.

In any case, Russian porter at the end of the 19th century was brewed using German-style double-decoction mashing, but top-fermentation: in 1898 L. N Simonov wrote that while for most beers in Russia “mainly bottom fermentation is used,” for black beers Russian brewers used top-fermenting yeasts, “because bottom fermentation is not suitable for these varieties.” (L.N. Simonov, Пивоварение (заводское и домашнее), Квасоварение и Медоварение (“Brewing [factory and home], Kvass Brewing and Honey production”), St Petersburg, Russia, 1898, pp408-9

Sorry, but wrong quote again. On page 408 it is written:

«Здесь мы разсмотримъ способы приготовленiя ангiлскихъ сортовъ пива — портера и эля, русскаго портера, русскаго чернаго пива и берлинскаго белаго пива». (Here we will examine ways of preparing English sorts of beer – porter and ale, Russian porter, Russian black beer and Berlin white beer).

And yes, Simonov talks about top-fermented beers in this abstract.

Does it means that this is the only way to ferment porter?

And did I say anything about XIX century concerning bottom-fermented porter?

I will continue…

Did you look at the Carslberg brewing record I posted on my blog? There are several brews using Evershed yeast, others using Cartlsberg yeast. Carl Jacobsen was clearly brewing both top- and bottom-fermenting beers in the early years of Ny Carlsberg.

The brewing book is Carl Jacobsen’s personal one. It also includes William Younger and Evershed brewes. A fascinating document. He was clearly heavily influenced by his time in the UK.

Hi, Ron!

Thank you for the link. But probably this is misunderstanding: I meant that the first lager porter was made at Carlsberg (not in Poland), but not the very first Carlsberg porter was lager.

Did you get the first lot of labels? Did I use the correct address?

Here are pair links to photos with “lager stout” brewed in beginning of XX century under private TMs I made in Carlsberg archive in 2011:

http://storage.ning.com/topology/rest/1.0/file/get/2174187902?profile=original

http://storage.ning.com/topology/rest/1.0/file/get/2234129702?profile=original

Doesn’t prove anything, I’m afraid: as I said, just as likely – more likely – to mean a stock stout than one brewed with lager yeast. And here’s a “Pure Lager Stout” from an Australian brewery some time, judging by the design around or before World War One.

http://www.vblcs.com/labelsdetails.php?brewerycode=6.18

Carlsberg definitely brewed a Stock Porter. This 1873 brewing record clearly shows a Porter described as “Keeping” with a higher hopping rate than standard DBS. Still being fermented warm, too.

https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-KE6bo2ikO40/YCrNrGN3ciI/AAAAAAAAiwQ/EI4e8zgGDxkfw18Ia9QQ70-eNzmaH9f_wCLcBGAsYHQ/s2048/Carlsberg_1873_Keeping_Porter.jpg

https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-wriVnDWTWLo/YCrPDWGVVbI/AAAAAAAAiwg/LLSDLrLiq4cJnvryst4xDtHOm9rPyDdbACLcBGAsYHQ/s320/Carlsberg_1873_Keeping_Porter_2.jpg

” Doesn’t prove anything, I’m afraid: as I said, just as likely – more likely – to mean a stock stout than one brewed with lager yeast. ..”

This dispute seems to be more theological, than historical. All the arguments of opponents are “total nonsense”, because they don’t fit the True Faith, even is this Faith is based on wrong and snatched out of a context quotes, wrong translations, absence of facts and evidences, speculative conclusions and marketing insinuations and myths. I am talking about both our sides. But truth is somewhere in between, right? 🙂

But anyway let us take a look at two points of theological atmosphere in discussion:

1. In the end of XVII century there was a strict and about two hundred years old definition between beer and ale. Beer was hoped, ale – not. Porter was “heavily hoped”, so porter was beer and that’s why mention of porter as ale in a work of Judith Drake, who could not even know about this definition, may not be considered as one of the earliest mention of porter.

2. In the beginning of XX century in the whole continental Europe including Russia there was already a strict definition between ale and lager. Ale became top-fermented beer, lager – bottom-fermented. But brewery, which 40-50 years ago had developed pure lager or bottom-fermentation yeasts, while labeling its beer used a combination of German “lager” and English “stout” to indicate that this was stock stout. It was very hard to print “stock stout”, I suppose, and there was a need to create some neologism to ruin that strict definition. Frankly speaking I expected to hear something about “just strong lager”, but “stock stout” is also good. May I kindly ask for some other examples of “lager ales|porters|stouts” meaning their stocking of beginning of XX century if you think it was common to label them in such a way?

“This dispute seems to be more theological, than historical. All the arguments of opponents are “total nonsense”, because they don’t fit the True Faith, even is this Faith is based on wrong and snatched out of a context quotes, wrong translations, absence of facts and evidences, speculative conclusions and marketing insinuations and myths.”

I’m sorry you’re having such an emotional reaction to your points being shot down by actual, verifiable facts – NOT myths. I don’t do “faith”. If I did “faith”, I’d still be faithful to the idea that Ralph Harwood invented porter in 1722 as an answer to three-threads, which was the myth faithfully repeated for 200 years. As I researched the story, however, it became clear that it wasn’t true.

You may be right about it being a “myth” that Catherine II drank what later became known as “Imperial stout”. But it’s a fact that, discussing the possibility of war between Great Britain and Russia in 1791, and the likely fallout of the dispute between the two countries, Catherine said: “пива и портера не будетъ”, “There will be no beer and porter”. (Indeed, a Russian historian, V. S. Lopatin, wrote a study of the 1791 crisis actually titled “Пива и портера не будетъ”.) The quote shows that the loss of imported porter was something that concerned the Empress, even if, as has been suggested, her words were said in a joking way. And it’s a fact that even before she died people in Britain were referring to extra-strong porter being brewed “specially for the Empress of Russia” at the Thrale/Barclay Perkins brewery in Southwark, while just 20 years after her death a history of the county of Surrey, which then included Southwark, said that the porter of Barclay Perkins’s brewery “used to be in great request with the Empress Catharine [sic] at Petersburgh.” (Owen Manning and William Bray, The History and Antiquities of the County of Surrey, vol III, London, England, 1814, p589). That would have been a fact people who had worked at the brewery had passed on. So there are at least three solid pieces of evidence, actual facts, linking Catherine and her court with porter, one of them involving very strong porter. There are also other evidences, such as the seed money she allegedly gave Abraham Krohn to start his brewery in St Petersburg (THAT, I will concede, could well be a myth promulgated by the Krohn family), the ordering of porter for the Russian fleet from a brewery in Southwark that I mentioned earlier, and the porter served up at the feast thrown by General Suvurov, Catherine’s favourite general, in 1793 for Nogai tribesmen in Kuban, close by the Sea of Azov, in 1793 –if a Russian army was wandering around the Crimea/North Caucasus area with casks of English porter among its supplies, this must have been something organised in St Pwetersburgh. So Catherine II has a role in the story of porter.

Please don’t accuse me of using “faith” rather than facts – it’s actually libellous, and it shows a deep lack of respect for the considerable amount of hard work I have put in over the past 25 years to try to make the history of beer fact-based rather than myth-based. It’s also particularly hypocritical of you when you are attempting to claim that “lager stout” means “stout brewed like a lager” when not only do you have no evidence for that, but your claim flies in the face of the fact that “lager” in Danish means “stock”. Your attempts at sarcastic jibes miss badly – “It was very hard to print ‘stock stout’, I suppose …” Well, yes, Carlsberg is a Danish firm, that’s why the label used the Danish word and not the English one. You also have a habit of throwing in straw men – “if you think it was common to label them in such a way.” I never said it was common to label stock stouts “lager stout” at all, although I did give a link to an example from Australia. It was very uncommon. What is TOTALLY unknown, however, is the labelling of those stouts known to be brewed using bottom fermentation, in Poland, in the United States, or anywhere else, as “lager stout”. So, to repeat, the idea that “lager stout” on a label means “this beer contains a stout brewed like a lager” not only has no evidence to back it up, it is also highly unlikely. The “wrong translations, absence of facts and evidences, speculative conclusions” are all on your side, I am afraid.

Talking of “wrong translations”, on one of your blog posts from 2016, http://www.beercult.ru/profiles/blogs/crimeaporter2 you speculate about the meaning of the phrase “Sago brandy” in a report by the German writer Johann Friedrich Anthing of a feast held by the Russian general Alexander Suvorov, and come up with several suggestions as to what that might mean. In fact “Sago brandy” is a mistranslation by whoever translated Anthing’s original book from German into English: the word Anthing actually used was “Kornbrandewein”, the 18th-century spelling of the German word for grain spirits. Translations should, indeed, always be checked.

Dear Martin!

It is very hard to run a discussion in several directions. We have disagreements in three major themes:

1. High popularity of porter at Russian Emperor court

2. Origin of “porter” term

3. Origin of Baltic Porter

Let us sort out the question of Russian Emperor court firstly. Provided the following reasons of your point of view.

Utugu, käzipaikku, pualikku

Dear Martin!

“…and it shows a deep lack of respect for the considerable amount of hard work I have put in over the past 25 years…”

I do apologize if you feel like this. I did not want to give you any offense. Please excuse me, I do respect what you do and I’ve got much knowledge from your materials. But respect is to be mutual and “total nonsense” for opponent’s arguments is far away from the term “politeness” as well. So my sarcasm was sent towards “total nonsense”. I will try not to use sarcasm in our discussions.

Regarding Lopatin…

Yes, a book with this name was published in 2003. And what?

I gave you a concrete quote from a diary of Khrapovitsky.

It is written what is written. The doesn’t show anything concerning import of beer and porter, attitude of Catherine II to porter and popularity of porter at the court.

From the quote is clear the one thing: Catherine II knew what porter was and porter existed in Russia in 1791, nothing else. The rest is excogitation of Vyacheslav Lopatin.

“So there are at least three solid pieces of evidence, actual facts, linking Catherine and her court with porter, one of them involving very strong porter”.

May I ask to name again these three solid pieces of evidence?

It is very hard to run a discussion in several directions. As I can see, we have disagreements in three major themes:

1. High popularity of porter at Russian Emperor court

2. Origin of “porter” term

3. Origin of Baltic Porter

Let us sort out the question of Russian Emperor court firstly.

I will try to summarize all your arguments in one letter.

For me story of Catherine II seems to be very dogmatic and I am Catherine II atheist.

Regarding Danish word lager.

Did I get right that Carlsberg used Danish word “lager” of German origin for Danish consumers to describe “stock stout”, because consumers understood “lager” and did not understand “stock”?

At the same time I’d like to designate two points:

1. In continental Europe in the beginning of XX century there was already a definition between ale and lager. And lager became a synonym of bottom-fermented beer.

2. This label is in Spanish for export. I am not sure that Spanish speaking consumers knew any Danish word.

Crimea and porter

Well, Martin, may I also kindly ask you not to use in our discussions this kindergarten way of communication “And you, and you yourself!!!”? In my post on Crimean porter I say that I have no idea what author of article meant under “sorgo brandy”. Probably, it could be buza or rakia (arak), which is grain spirit with anise in fact. And then I put a historical quote what was Crimean buza – popular drink among Crimean tatars similar to kislye shchi (mint sour ale). Where did you find any speculation?

“The Empress of Russia is so partial to Porter, that she has ordered repeatedly very large quantities for her own drinking and that of her Court.” (Matthew Concanen junior and Aaron Morgan, The History and Antiquities of the Parish of St. Saviour’s, Southwark, London, England, 1795, p23) So that’s one source from 1795 and one from 1796 (from Faringdon’s diary), both within the lifetime of Catherine II, both indicating that Catherine and/or her court liked and drank porter, both (independent) sources clearly deriving their information from people at, or close to Barclay Perkins’s brewery. If two independent contemporary sources are saying the same thing, that pushes the balance of probability well over towards “likely”. Certainly it was believed in Britain at the time that Catherine liked and drank porter.

“Where did you find any speculation?” Where you speculated that “sago brandy” could be rakia or buza. It’s OK to speculate, and I was inclined to speculate that myself, except that I could not see, or find, any link between sago and any of the grains used to make buza or rakia. That’s why I dug deeper, and found the German original, which, of course, doesn’t mention sago at all.

As for “lager stout”, “lager” isn’t a “Danish word of German origin”, it’s a Danish word from the same Germanic root (which gave English the word “lair”). It seems to me to be very unlikely that Carlsberg would want to tell Spanish customers the stout it was selling them wasn’t made like English stout, and on the balance of probability I believe it’s much more likely that “lager stout” meant “stock stout”.

“Try to imagine high-class Champagne and working class-porter on the same table in aristocratic house.”

Arthur Guinness was supplying Dublin Castle with porter in 1786. The Prince of Wales, the Duke of Devonshire, the Duke of Norfolk and other aristos drank porter with beefsteaks at Harvey Combe’s brewery in Covent Garden, London in 1805. In the early Victorian period, “Beer was universally taken with dinner” and “even at great dinner parties some of the guests would call for beer. In the restaurants every man would call for bitter ale, or stout, or half-and-half [ale and porter mixed] with his dinner, as a matter of course.” (Sir Walter Besant, Fifty Years Ago, London, 1890, p240). Benjamin Disraeli wrote to his sister in 1837 that after a debate at the House of Commons he “dined, or rather supped , at the Carlton [Club] with a large party off oysters, Guinness, and broiled bones.” So yes, that’s easy to imagine.

“It could be in a case porter never was working class beer. Not in Russia, not in England.”

Oh, please. I do hope that you are either joking or trolling. And if you want evidence that the working classes in Russia drank porter just like the working classes in Britain, the German traveller Heinrich von Storch wrote in 1801 that in St Petersburg, consumption of “foreign beers and wines” by “the lowest classes” was “extremely great,” and “I myself have seen a parcel of isvoschtschiki [hackney coach drivers] empty several dozen bottles of porter between them.” (Heinrich Friedrich Von Storch, The Picture of Petersburg, London, England, 1801, p120)

“Well, I do believe that etymology of “porter” goes out from Dutch “poorter”, not from a working-class profession.”

The evidence is overwhelming – utterly, utterly irrefutable – that the name of the beer comes from the name of the people who drank it, the porters of London. Every 18th century commentator who talks about the origins of the name says so. The idea that “porter” the beer might come from “poorter” is purely a late 20th century invention, with not an atom of evidence in its favour, and a host of reasons why it can’t be true, not least because there are NO mentions of a Dutch beer called poorter being on sale in England. To quote Roel Mulder, an eminent Dutch beer historian writing in a comment on this blog six years ago: “The main problem is, that poorter never was a beer style to begin with. ‘Poorter’ means citizen (or it did, because by the 18th century it has given way to the current word with that meaning, which is ‘burger’), and so there are various documents about citizens (‘poorters’) being in a different tax category when they brewed beer. A nice example is Antwerp, where from the 16th to 18th century there were city breweries where citizens (again, ‘poorters’) could have their own beer brewed. The misconception is, I think, that their beer wasn’t necessarily of a different beer style; and it’s hard to see why it would develop into one. English porter being advertised as ‘poorter’ in Dutch newspapers from the late 18th century is more likely to come from lack of knowledge of the English language than anything else. Never has anything like ‘poorter’ been advertised in a Dutch newspaper as anything else than English porter, and by the time ‘poorter’ is occasionally used in Dutch to describe English porter, the original Dutch word ‘poorter’ for citizen had fallen out of use.”

“Cross took this information not from some ‘list of enterprises in St Petersburg’ but from the book by Johann Gottlieb Georgi ‘Description of capital town St.Petersburg’ (1794, pages 243-244). I can disagree with this statement, cause I found more.”

“A list of enterprises” is what Cross called it. That’s a quote from his book. I would be delighted to see your list of St Petersburg brewers: does it indicate which of them was brewing porter? Please do email me.

“Danielson was from Finland from Tavastehus (Hämeenlinna)”

Please do let me have a source for that.

“Friedrich was Danielson, not Danielsen.”

He is found in sources with both spellings. I am happy to be assured that it is one or the other, provided ypu have actual documentation

“I can send you labels of Ny Carlsberg with ‘lager stout’ sign.”

Unfortunately that doesn’t mean anything, as “lager” in Danish, just as in German, means “stock” or “store”, as in the English term “stock beer”, “beer kept in store”, “aged beer”, so “lager stout” almost certainly meant “aged stout”, stout that had been “lagered” – stored – rather than “stout brewed like lager”,. And why would you advertise to drinkers that your stout was brewed like a lager anyway? You’d want them to think it was as much like the English version as possible, surely.

“Sorry, but wrong quote again.”

I fail to see any error by me here, only you admitting that I’m right.

Further to my comments above, the beer that Peter drank and presumably enjoyed (otherwise why would he go to the trouble of setting up an English-style brewery in Moscow?) could have been a very early proto-Porter. However, at this point it might not have been called “Porter”, and therefore wouldn’t have been recorded or mentioned under that name.

Just because nobody in 1698 used the name “Porter” doesn’t mean that the beer Peter came to enjoy in Deptford wasn’t a very early form of that beer.

Rod, you are damn right!

I am sure that in 1698 they use already name porter.

As I told you before, in 1696 «An Essay in Defence of the Female Sex» by British feminist Judith Drake was publish, in which we may read this passage:

“Not a pot cou’d go glibly down or a stitch go merrily forward without namur, a while ago; ‘twas spice to porter’s ale, and wax to the cobler’s thread; the one suspended his draught, and the other his awl to enquire what was become of the rogue, and were very glad to hear he was taken, and expected no doubt he shou’d come over and make ‘em a holiday at his execution”,

I do believe this is the earliest mention of porter. Ron Pattinson disagrees with me, considering porter as beer, i.e. hopped one, not ale.

So Peter The Great might drink porter in England, but unfortunately we can not prove it yet. And unfortunately the earliest mention of porter in Russian press dates back to 12th of January 1767. And Peter died in 1725.

I hope some day we can find more facts about Peter I and porter.

“Ron Pattinson disagrees with me, considering porter as beer, i.e. hopped one, not ale.”

Ha ha – not everyone has Ron’s laudable exactitude when it comes to the distinction between “ale” and “beer”.

Judith Drake may not have known or cared about the difference, so the fact that she, maybe mistakenly, refers to Porter as ale doesn’t really mean anything in this context, in my opinion.

[If Porter gets its name ]”….from working class profession it is very hard to explain how the beer with this name could become popular at Russian Imperial court and high society. ”

Well –

If – Peter did get the taste for the workmans’ beer in the dockyards at Deptford, and

If – that beer was an early form of Porter (which may have been called London Brown Beer, or Entire Butt, or something else), and

If – the English brewer in the Kremlin was brewing a form of Porter, and

If – Peter drank this Porter in the Court, then

his example would very likely have encouraged his courtiers to take up Porter drinking, and may have started the trend in St Petersburg of Porter drinking.

Obviously this is conjecture, but if the Tsar drank this exotic beer, it would not, perhaps, have been seen as a proletarian drink – quite the opposite.

Or it could all be a myth!

Or the term goes out not from a working class profession, but from Dutch “poorter”. Peter The Great spent more time in Holland than in England and many foreign words in XVIII century came to Russian mostly from Dutch, not English. We still call orange “apelsin” in Dutch way for instance.

“Or the term goes out not from a working class profession, but from Dutch “poorter”.

Well, Freek Ruis, that valiant defender of Dutch beer history and traditions, has suggested that the English name “Porter” may come from the Dutch “Poorter”, but he doesn’t seem to have a lot of evidence for that, and he even admits that next to nothing is known about old Dutch Poorter, and that it may not even have been what we would nowadays recognise as a style.

It’s really not clear to me why you think the fact that the English name “Porter”, allegedly derived from a class of working men, would have proved such a problem in Russia. Did many upper class Russians in those days actually speak enough English to have a chance of understanding the proletarian connotations of the name?

Ron has said that some kinds of very strong black beer were very much considered an upmarket drink, being very expensive, and Martyn has pointed to the fact that people such as George Washington and the Prince Regent drank Porter.

I have sketched, in my comment immediately above, a hypothetical scenario whereby the Tsar may have set a fashion for Porter drinking.

You yourself have spoken of Anglomania in St Petersburg, which may have made Porter seem quite prestigious.

Finally why would Peter the Great, or anyone else, use an obscure Dutch word for a beer that he (may have) discovered in London, given that he imported an English brewer to come and set up an English brewery in the Kremlin?