The “IPA shipwreck” is one of many long-lasting myths in the history of India Pale Ale. The story says that IPA became popular in Britain after a ship on its way to India in the 1820s was wrecked in the Irish Sea, and some hogsheads of beer it was carrying out east were salvaged and sold to publicans in Liverpool, after which the city’s drinkers demanded lots more of the same. Colin Owen, author of a history of Bass’s brewery, called the tale “unsubstantiated” more than 20 years ago, and others, including me, being unable to find any reports of any such wreck, nor of any indication that IPA was a big seller in the UK until the 1840s, have dismissed it as completely untrue. Except that it turns out casks of IPA did go on sale in Liverpool after a wreck off the Lancashire coast involving a ship carrying hogsheads of beer to India, a shipwreck that, literally, became a landmark – though not in the 1820s – and the true story is a cracker, involving one of the worst storms to hit the British Isles in centuries, which brought huge destruction and hundreds of deaths from one side of the UK to the other.

The story of the IPA shipwreck first turns up in 1869 in a book called Burton-on-Trent, its History, its Waters and its Breweries, by Walter Molyneaux, who described how the Burton brewers began brewing beer for export to India from 1823. Molyneaux wrote: “India appears to have been the exclusive market for the Burton bitter beer up to about the year 1827, when in consequence of the wreck in the Irish Channel of a vessel containing a cargo of about 300 hogsheads, several casks saved were sold in Liverpool for the benefit of the underwriters, and by this means, in a remarkably rapid manner, the fame of the new India ale spread throughout Great Britain.”

Molyneaux’s story has been regularly repeated in the past century and a half. But no one has been able to find a wreck that matched up with his story. This turns out to be, not because the wreck didn’t happen, but because he was 12 years out with the date.

The year after Molyneaux’s book came out, a different version of the tale appeared in the “notes and queries” section of an obscure publication called English Mechanic and World of Science. The account was written by a man who gave himself the name of “Meunier”, and it said: “Forty years ago [ie about 1830] pale ale was very little known in London, except to those engaged in the India trade. The house with which I was connected shipped large quantities, receiving in return consignments of East Indian produce. About 1839, a ship, the Crusader, bound for one of our Indian ports, foundered, and the salvage, comprising a large quantity of export bitter ale, was sold for the benefit of the underwriters. An enterprising publican or restaurant keeper in Liverpool purchased a portion of the beer and introduced it to his customers; the novelty pleased, and, I believe, laid the foundation of the home trade now so extensively carried on.”

The two clues – the ship’s name and the later date – together with the fact that large numbers of newspapers from the time have now been scanned and made available on the web make it easy to trace the story at last. The Crusader was a 584-tonne East Indiaman, or armed merchantman, described as “a fine large ship with painted ports [that is, gun-ports] and a full-length figurehead”, “newly coppered”, that is, with new copper sheathing on the hull to prevent attacks by wood-boring molluscs, and “a very fast sailer”, under the command of Captain JG Wickman. She had arrived in Liverpool early in November 1838 after a five-month journey from either Calcutta or Bombay (different Liverpool newspapers at the time gave different starting ports) with a cargo including raw cotton, 83 elephants’ tusks, coffee, wool, pepper, ginger – and opium, which did not become illegal in Britain until 1916. Captain Wickman and his crew were due to leave for Bombay again on Saturday December 15, after five weeks of roistering in Liverpool, with a cargo that included finished cotton goods, silk, beef and pork in casks, cases of glass shades, iron ingots, tin plates, Government dispatches – and India ale in hogsheads, brewed by two different Burton brewers, Bass and Allsopp, the whole lot being insured for £100,000, perhaps £8 million today.

However the Crusader did not leave on the 15th, possibly because of adverse winds, which certainly kept increasing numbers of ships in Liverpool from Christmas onwards. Finally, on Sunday January 6, 1839, the wind changed, blowing a south-westerly breeze, and some 60 vessels, including the Crusader, left the port. What none of those sailors on board the fleet sailing out from the mouth of the Mersey knew was that a massive, fast-moving depression was coming in across the North Atlantic, travelling from the west-south-west at around 40 to 50 knots. It was bringing hurricane-strength winds, which would batter towns and cities from the west coast of Ireland to the east coast of England, uproot millions of trees, smash down thousands of chimneys, sink hundreds of boats and kill several hundred people. In Ireland, where estimates have suggested between 200 and 400 people died, that Sunday became known as the Night of the Big Wind. Thousands of houses and cottages were stripped of their roofs from Galway to Armagh, with many left on fire. Limerick resembled “a city on which a park of artillery had played for a fortnight.” In Belfast “not a roof escaped”, while Dublin looked, according to one newspaper report, as if it had been sacked by an army, with houses burning or levelled to the ground, and “the rattling of engines, cries of firemen and labours of the military” presenting “the very aspect and mimicry of real war”.

The winds seem to have struck the west coast of Britain late on the evening of Sunday 6th, and did not finally ease up until Tuesday morning. The lowest air pressure measured was about 922.8mb at Sumburgh Head, Shetland around 2pm on Monday 7th, the third lowest figure ever seen in the British Isles. The effects of the storm were felt in London, with “numerous” chimneys blown down in and around Islington and Camden Town, but were far worse in the North: nowhere from one side of the Pennines to the other seems to have been spared serious damage. In Liverpool, thousands spent a sleepness night listening to slates and bricks crashing down into the streets, as even “the best built houses rocked and shook” with the winds, and at least 20 people were killed by falling masonry. In Manchester, where six people died, so many factory chimneys were blown down, it was reckoned between 12,000 and 15,000 workers would be laid off for weeks before the chimneys could be rebuilt and the steam engines that powered the factories restarted. In Bolton, it was said, “not a house escaped”, in Blackburn alone 11 factory chimneys were felled, and in Newcastle upon Tyne “almost every building suffered, more or less”. In Ayr “the streets are covered with slates and chimney cans”, and in Dumfries “the noise during the entire night was more deafening than the battle field”. Birmingham and Wolverhampton, like many other towns and cities, had scarcely a street where houses had not suffered: much of the roof of Birmingham Town Hall was torn off, with lumps of lead weighing almost half a ton crashing into the street or onto nearby houses. Among the windmills demolished were five at Bridlington: others, such as the water company’s windmill in Newcastle upon Tyne, were set on fire by the friction caused when the fierce winds set their sails rotating far faster than their builders had thought possible. In Barnsley, the lead roof was lifted off the Methodist chapel and more factory chimneys demolished, while Leeds saw at least eight mill and factory chimneys levelled, and a church lose 24 feet off its spire. Hayricks were destroyed, pedestrians blown into the air and innsigns made to fly. One remarkable phenomenon reported by the newspapers after the storm was a covering of what appeared to be seasalt on hedges, trees and houses in districts far inland, such as Huddersfield, more than 50 miles from the coast.

Out at sea, the effects of the storm were terrifying and terrible, with ships in peril from the mouth of the Shannon to the mouth of the Humber. Many of the vessels that had left Liverpool on the Sunday escaped the rage of the winds: but many others did not. Ships on their way home from ports far away, and close to the end of their journeys, were also caught. Between 30 and 40 vessels were either sunk or run aground in the Mersey area alone. Several went down with all their crews drowned. Those ships that ran onto sandbanks were then battered by the high winds and huge waves, and began to break up. Lifeboats could not get out to rescue the passengers and crews until the storm lessened, and when rescuers did arrive, they found many of those they were seeking to save had died of exposure in the preceding hours, on deck or in the rigging. The Lockwood, an emigrant ship bound for New York, which had got as far as Anglesey on the Sunday before being driven back by the storm, had then struck sandbanks and begun to list. Of the 110 passengers and crew, 53 died before they could be taken off by rescuers. One of the Crusader‘s fellow East Indiamen, the Brighton, returning from Bombay, struck a sandbank in the mouth of the Mersey on the morning of Monday 7 January and started breaking up. Some 14 of her crewmen made a raft and launched it into the mountainous waves to try to reach land. They were never seen again. The captain and his remaining crew had to cling to the rigging until Tuesday morning before they could be saved by the Liverpool lifeboat.

What happened to the Crusader while she was out at sea appears to be unrecorded, but like other ships she was driven back by the violence of the storm, or, having failed to get past the tempest, tried unsuccessfully to return to the safety of port. On the morning of Tuesday 8th January, nearly two days after she had left Liverpool, and after a “fearful night of wind, hail, thunder and sleet and forked lightning”, the Crusader was seen just off the coast at Blackpool, more than 25 miles north of the Mersey. She had struck a sandbank that is still, today, named Crusader Bank, in her memory, and suffered “much damage”. The ship’s crew were firing the Crusader’s guns to try to attract attention onshore, but soon after, according to the Blackburn Standard newspaper, “two boats put from her, and after crossing the breakers, landed a crew of 26 seamen, when a loud huzza proclaimed their safety.”

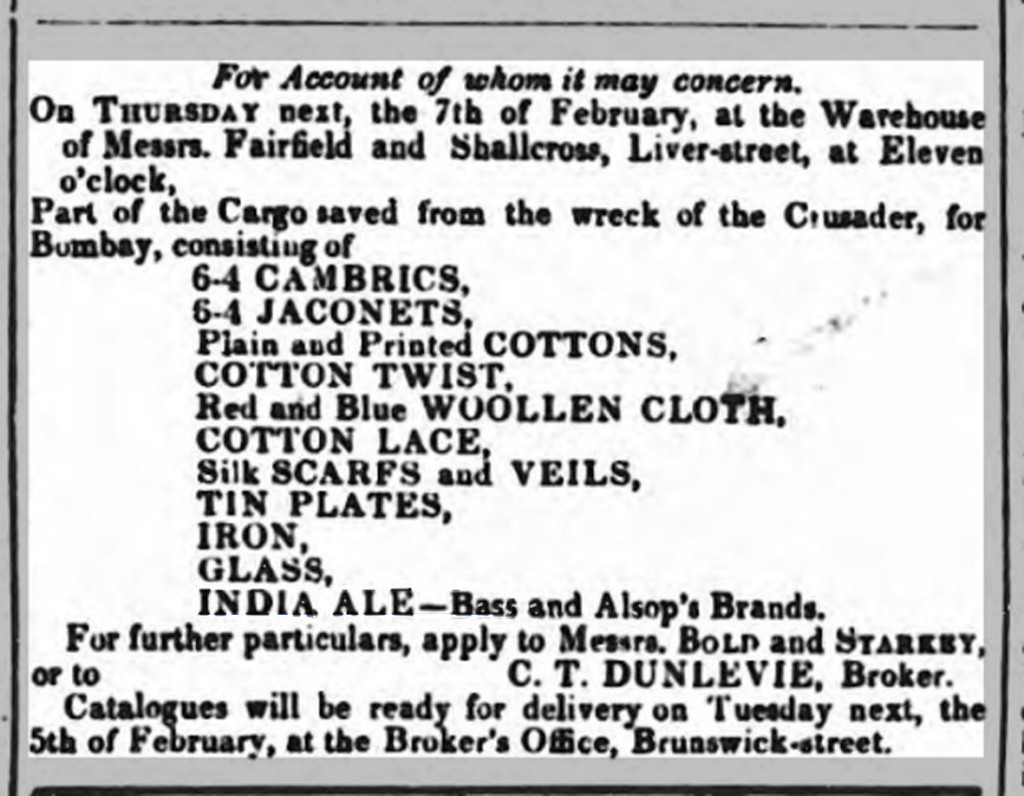

While the crew were safe, however, the ship had broken her back, and with her hull being almost covered by water at half-tide, her cargo began to wash up along a 15-mile stretch of coast from the Ribble in the south to the Wyre in the north. “A great deal” of the cargo, however, was gathered in by customs officers and locked up, including 79 hogsheads of ale that had been driven on shore, along with other goods, on January 16. (There was much cargo from other ships also cast up on the coast, along with dead bodies from ships that had sunk.) The Crusader began properly to break up only on Sunday 17th February, more than five weeks after she had run aground, though she then fell to pieces within four days. However, the first sale of cargo saved from the wreck of the Crusader had already taken place in Liverpool on Thursday 7th February. It included cotton fabrics, woollen cloth, silk scarves and veils, tin plates – and “India ale, Bass and Alsop’s [sic] brands”.

Another two sales of goods saved from the wreck of the Crusader, including more India ale, were held in Liverpool on March 14 and March 28. (There were three more sales of items from the ship, in May, June and July, including broken rigging, chains, pumps and anchors, but no more beer).

The story is true, then, that casks of beer destined for India and rescued from a shipwreck in the Irish Sea did go on sale in Liverpool, though at the end of the 1830s, not the middle of the 1820s. But were these sales in Liverpool of several dozen hogsheads, at least, of India ale brewed by Bass’s brewery and Allsopp’s brewery in Burton upon Trent the foundation on which was built the popularity of IPA in Britain? Alas, there is still no hard evidence for that part of the story: and what evidence there is suggests even Liverpool knew about IPA before the Crusader went aground. Beer brewed for the India market had been available in Liverpool since at least 1825, when the Middlesex brewer Hodgson’s of Bow, one of the earliest suppliers of pale ale to the Far East, had an agency in Liverpool for the sale of “pale bottling ale” to “merchants and others”. The first known use of the expression East India Pale Ale in a British publication actually comes from a Liverpool newspaper, but in 1835, four years before the Crusader shipwreck, when Hodgson’s beer, again, was being offered to “merchants and private families”.

Judging by the surge in adverts for IPA in London newspapers, the real take-off for the beer’s popularity appears to be a couple of years after the Great Storm, in 1841. That was certainly the year when Bass finally opened a store in Liverpool for the sale of “pale India ale”, declaring in a notice in Gore’s Liverpool General Advertiser on April 22nd that announced the new store that “This ale, so long celebrated in India, has now become an article of such great consumption in this country (where it is almost superseding every other sort of malt liquor)”, and at the Burton Ale Stores in Ironmonger Lane “a Stock is kept of an age suitable for immediate consumption”. Was this, two years on from the wreck of the Crusader, a result of that ship’s cargo having gone on sale in Liverpool? The verdict here, I think, has to be “not proven”.

Why Molyneaux got the date of the IPA shipwreck so wrong is a puzzle, when there would have been many alive in 1869 who could still remember the Night of the Big Wind 30 years earlier. But while it is part of Ireland’s folk memory – there are poems, and a novel, written about it – the 1839 storm is pretty much forgotten in Britain, probably because in this island it was only the second-worse storm of the 19th century, beaten in impact by the so-called Royal Charter storm of 1859. This was named for a ship that went down off Anglesey with the loss of 450 lives. Another 350 people also died during that storm, which sank 133 ships.

As a footnote, although large numbers of factories were damaged in the 1839 storm, breweries seem to have got off lightly. Newstead and Walker’s brewery in Bolton saw “considerable” damage. In Borrisokane, Tipperary, “the chief part of the Ormond brewery was blown down”. In Dublin, nine horses belonging to Guinness & Co were killed in their stalls by a falling wall. That, however, appears to be it.

Martyn,

You have done it again -such an interesting and well researched story !!!

Many thanks for that !

Gerard

Well-done, Martyn, and commendations for having written a real story, rather than a simple reporting about THE BEER. Dogged and honest.

What’s your earliest date for any beer shipped to India, Martyn? Anything prior to the 1750s? With these slightly later dates, I am wondering about the function the Bristol trade to America may have played in proving the concept of the oceanic beer trade.

English beer was being drunk in 1638 at Surat, in Gujarat, North West India*, where the East India Company established its first big trading post, so certainly as early as that … I’m sure beer must have been exported out of Bristol, but nobody seems to have done any real research on it …

*Edit: that’s what Pete Brown says in Hops and Glory, but I’ve now tracked down the actual source he used, and it’s not quite that simple …

All the American trade seems to be out of Bristol before the Revolution. It is too bad no one will get over there to find out what’s in the records. Do you know if the Gujarat beer was actually imported for consumption as opposed to being brewed there or present as sailors’ harbour beer? I’ve got 1670s brewing in the Arctic. The Hudson Bay Co and EIC would have been buying supplies from similar suppliers.

I agree – calling all Bristolian beer historians, there’s a job to be done …

The beer was described specifically as English, though whether ship’s beer or specially imported is unclearCorrection: I’ve now tracked down the actual source used by Pete Brown in Hops and Glory: when we meet it, the beer wasn’t actually being drink IN Surat, in fact: the German traveller Johan-Albrecht Mandelslo sailed in April 1638 from “Gamron”, or Bandar Abbas, in Persia, on the Straits of Hormuz, to Surat on an English ship, the Swan, which had aboard “excellent good Sack, English Beer, French Wines, Arak and other refreshments”. So the beer was for the use of those on the ship: and as it was an English ship, we can suppose it was English-brewed. We can guess that some survived to be drunk in India, because Mandelslo talks about drinking “Sack and English Beer” in Ahmedabad, then the capital of Gujarat, that he and his companions had brought with them from Surat.

Rest assure that English beer must have been available there around that time. It was definitely in Dutch East India, the former colony that is now called Indonesia, only a couple of years later. In the ‘General messages of the governor and councillors to the board of the Dutch East India Company’ (sources published from 1960 onwards) English beer is mentioned for the first time in 1645 – and in what way! In february 1645 the governor and his staff wrote to Holland saying that ‘the English friends […] supply us very well with English beer, which makes up the most of their cargo’s brought from England’. Dutch beer was sent there too, but by that time very little and sometimes having become sour. It would take another 30 or 40 years for more and better beers to get there. In the meantime, English traders and their beers became very popular and successfull in the capital Batavia (which is now Djakarta). So as it was traded there it must have been traded in India too, and probably even earlier.

Absolutely fascinating, Marco, thanks very much for that indeed.

Take care with ’English beer’ as it was a popular beer-style and brewed all over the Low-countries in the 16-17th century. I even have a 17th century Dordrecht recipe of English beer.

To supplement my earlier reaction:

I have now published a special archive of ’English beer’ on the continent including an early 16th century permission to brew it in Middelburg and a remarkable recipe by De L’Obel of 1581. It further contains evidence of English beer being made in cities like Delft and Dordrecht.

My conclusion is that this hopped English beer was a beer-style that could be made anywhere and probably originated from the Low-Countries brewers in England. It was distinctive because of the large amounts of barley used, where other styles would have all kinds of other grains used.

All kinds and lots of continental beers where brought to the East in the 17th century.

We know that from archives like the Administrative centre of the Dutch East India Company in Batavia and the ‘Generale missiven’, the Internal reporting to the Lords 17 of the Company. Off-course they could sometimes become sour but one can gather from the sources that this was exceptional and sometimes due to circumstances like illegal drinking from barrels during the voyage.

Tremendous – thank you very much. The interaction between Low Countries brewers in London and their cousins back home in the 16th and 17th centuries is very interesting

Well told and exciting!

Excellent stuff! The legend lives on.

[…] I England, derimot, var dette et ukjent øl i tyve år. Først rundt 1840 kom de første annonsene for «India Pale Ale» i avisene. En historie fra 1869 forteller at et skip som skulle til India forliste i den irske kanal i 1827 og at tønner med øl drev inn til land. Folk i Liverpool drakk ølet og ble begeistret. Lenge hadde man ikke klart å finne noe bevis for at et slikt forlis virkelig skjedde, og heller ingen dokumentasjon på at IPA ble drukket på land før på 1840-tallet. Men den iherdige Martyn Cornell er en ekte øl-historiker som graver og graver i gamle kilder. Og gjett hva han fant? Jo, en bekreftelse på at det virkelig var et skip som gikk ned i «The great storm», men i 1839, altså 12 år senere enn man lenge hadde trodd. Den komplette historien kan du lese om på Cornell’s blogg. […]

[…] https://zythophile.co.uk/2015/10/12/the-ipa-shipwreck-and-the-night-of-the-big-wind/ […]

[…] https://zythophile.co.uk/2015/10/12/the-ipa-shipwreck-and-the-night-of-the-big-wind/ […]